Across Africa, mastering traditional trade channels is an essential element of establishing a successful route to market. Even as Western-style retailing expands in countries such as Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa, traditional lifestyles and customs remain strong. BCG’s recent continent-wide survey shows 97% retail penetration by value in Nigeria’s traditional channels. The corresponding figure in Kenya’s traditional channels exceeds 70%.

South Africans are the only group in our 12-country survey of African consumers who told us that they buy more consumer products in modern channels than in traditional channels. In part, this reflects how rapidly South Africa’s four leading supermarket companies—Shoprite, Pick n Pay, Spar, and Woolworths—have grown in urban and suburban areas. But even though South Africa has the largest and most developed modern retailing on the continent, 30% of South Africans’ purchases by value across categories occur in traditional shops, and the number is even higher for certain products.

In South Africa, most fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies focus on reaching customers through superstores and grocery chains because they believe that these modern channels offer the fastest, easiest, and lowest-cost way to increase sales, market share, and brand awareness. Many of them also assume that customers of traditional shopkeepers don’t have enough disposable income to boost an FMCG company’s sales and profits. As a result, they tend either to neglect the traditional channels or to handle relationships with small shops indirectly through wholesalers.

This is a mistake.

According to BCG estimates, companies in South Africa are passing up a revenue opportunity of R100 billion to R130 billion, along with the chance to grow market share in a cohort of nearly 57 million brand-conscious and brand-loyal people.

To be sure, profitably serving South Africa’s traditional channels is a challenge. As elsewhere in Africa, South Africa’s multitudes of small, independently owned shops have limited capacity to partner with large suppliers. Nevertheless, our research shows that with the right investments and strategies, FMCG companies can overcome these challenges to reach millions of additional consumers who have the means and motivation to buy their products.

Most of the interviewees who participated in BCG’s biennial

Africa Consumer Sentiment Survey conducted in 2018

have household incomes of less than $500 a month. Their responses enabled us to show FMCG companies the strong potential for growth that exists among lower-income, aspirational consumers.

Our extensive primary research confirms that multinational and domestic FMCG companies in South Africa are missing out on big opportunities to stimulate sales and to establish a larger, stronger overall market presence. To achieve both of these goals, companies must build equally robust routes to market through modern channels and through traditional channels.

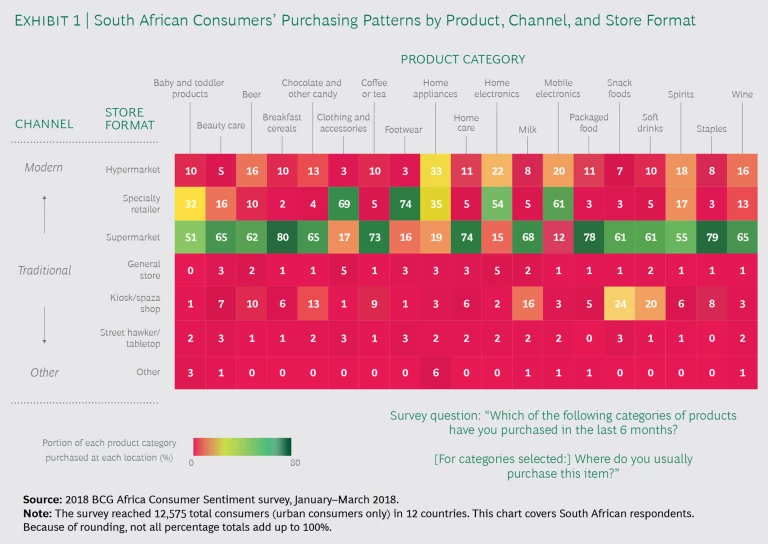

Two Views of South Africa’s Retail Trade

The consumers we surveyed in the 2018 biennial study said that the food and beverage category was the largest monthly recurring expense for their households, accounting for 24% of their monthly budget versus 17% for rent or mortgage and 11% for transportation. For example, survey respondents said that they purchased more than 75% of their packaged foods and more than 60% of their beverages (beer, wine, and soft drinks) in supermarkets. (See Exhibit 1.) This suggests that consumers do their big-basket monthly shopping in supermarkets because traditional retailers can’t match the volume and variety of products and brands that large modern markets can offer.

On the other hand, 69% of consumers said that they visited traditional shops more often than they did supermarkets. Our survey shows that even as South Africans increase their use of modern retail, they continue to frequent the traditional trade’s general dealers, spaza shopkeepers, and other specialty stores and taverns. (See "South Africa's Traditional Trade Formats.")

South Africa's Traditional Trade Formats

South Africa's Traditional Trade Formats

When our team performed its primary research on consumer behavior in South Africa in 2018, we conducted a survey and made site visits to 852 stores representing four popular traditional trade channel formats:

- General dealers. We visited 150 small to medium-size one-stop shops offering a range of branded packaged grocery items. Among the participants in our survey, 40% of general dealers said that they employed more than six people, while 10% were sole proprietors; 17% generated sales exceeding R100,000 per month.

- Spaza shops. These informal top-up and pop-up shops have unique roots in South Africa’s sprawling townships. They are convenient and popular: proprietors often operate within walking distance of their customers and are their neighbors. A proprietor might set up a spaza storefront in a garage or a living room. Almost 80% of spaza shops employ fewer than two people. Profits from a spaza may supplement an owner’s income from another job. The shops stock small quantities of multiple brands of household items. Their selection of products is limited by space and dictated by demand. Some sellers make their living selling a few types of items that they purchase from supermarkets or wholesalers. Most (90%) reported that they had sales of less than R45,000 per month.

- Health and beauty specialty stores. These small, informal stores-with or without a salon-sell hair care, skin care, and oral hygiene products; perfumes and lotions; and over-the-counter health products. In our survey 50% of these specialty stores employed more than two people, and 90% had sales of less than R45,000 to R50,000 per month.

- Shebeens and taverns. Shebeens are located in townships, and historically they were unlicensed. Today, most of them are licensed and serve a selection of commercial beers as well as a traditional South African beer made from corn and sorghum. Taverns are small liquor stores that stock multiple brands of spirits, wine, beer, and ciders. Some offer tables and seating on the premises. Most of the establishments in our survey were located within walking distance of customers’ homes. In our survey, 65% of the shebeens and taverns employed more than three people, and 60% had sales, on average, of less than R45,000 per month.

Our research shows that consumers do their small-basket and top-up shopping in traditional stores every week, or even daily, because they live within walking distance of a shop or because the shop lies along their commuting route to work. In our survey, 60% of general merchandisers, health and beauty specialty shops, spaza shops, and taverns were in residential areas, and 25% were near taxi stands. Such accessibility is a major consideration, given that survey participants identified transportation costs as their third-largest household expense.

In addition, even though major South African retail chains operate in multiple locations in major cities and suburbs, and have recently opened stores in some townships, consumers remain loyal to small-shop owners who are part of their community. These shop owners may extend credit to regular customers, stock a wider variety of small package sizes (for example, they may offer eggs for sale individually), or sell brands—especially hair care brands—that modern stores do not stock. We found that these reasons for shopping at traditional trade outlets remained true even if a Pick n Pay, Shoprite, or other familiar chain opened in a township.

We believe that by working more closely and effectively to support traditional retailers, FMCG companies could capture a much greater portion of the total amount that South Africans spend on frequent, small-quantity purchases. Although 80% of shoppers reported buying their breakfast cereals and 68% reported buying their milk in supermarkets—versus 6% who bought cereals and 16% who bought milk in spaza shops—there is no reason to suppose that they wouldn’t buy them from a local grocer, too. Similarly, frequently purchased products such as diapers offer major brands a big opportunity to capture more single-item packaged goods sales. For instance, in our store visits, we found that some spaza shops were selling a leading brand of diaper in single units at R5 each.

Looking Beyond Traditional Trade’s Barriers

Large FMCG companies favor investments in growth through modern channels and tend to see traditional channels as a limited opportunity and, therefore, a low priority. There are two reasons for this tendency. First, many FMCG companies incorrectly imagine that traditional trade customers have limited disposable income or don’t care about brands. Second, such companies are daunted by the distribution challenges involved in supplying and servicing a multitude of small businesses that lack infrastructure and may be unlicensed.

In our surveys, we have found evidence of strong demand for branded products (that is, products produced by a global or large-scale local manufacturer) among shoppers who use traditional channels. In the BCG 2018 consumer sentiment survey, 65% of respondents of all income levels agreed that “brands say something about who I am,” and 88% agreed that “all things being equal, brands that have been around the longest are the best brands.”

With regard to the number of different brands of products available on the shelves of traditional stores, we found considerable variation from one category to another. (See Exhibit 2.) Overall, the array of health and beauty product brands available (98) was significantly larger than the array of brands available in any other category. The next-largest numbers of brands available were in the categories of alcoholic beverages (64) and confectionary (50).

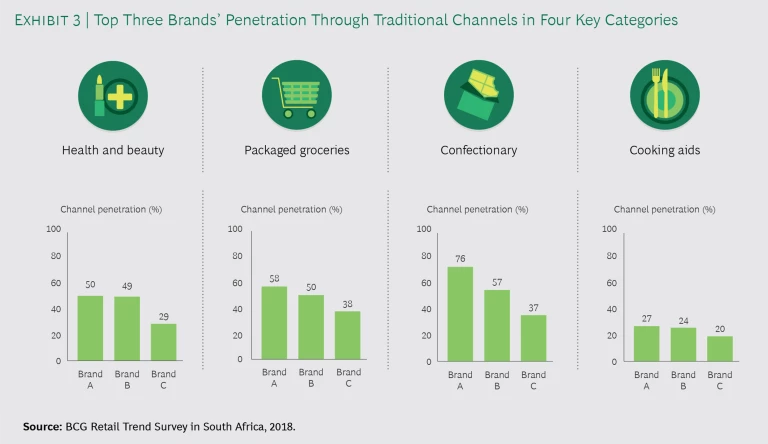

Although FMCG players are present in key categories, their absolute numbers and percentage penetration show that they are not maximizing their positions. Exhibit 3 shows the limited degree of penetration that the top three brands in each of four major product categories (health and beauty, packaged groceries, confectionary, and cooking aids) are achieving through South Africa’s traditional channels—a situation that leaves ample room for companies to expand their distribution footprint and market share. Meanwhile, companies that are not present at all may be losing valuable opportunities to competitors.

Four Key Operational Challenges

We explored a number of operational characteristics and variables for different types of traditional store formats, including layout, shelf space and display, products and brands stocked, supplier behavior and relationships, number of employees, tech adoption, customer behavior profiles, and theft and other risks. From our survey and from direct observation, we identified four significant route-to-market challenges that companies need to overcome.

First, dealing with highly fragmented retail markets is difficult and expensive for distributors anywhere. The fact that South Africa’s traditional trade is composed of small, informal, individually owned shops makes the challenge even greater.

Second, the absence of vital storage facilities and limited display space is problematic. For example, in our survey, only about 30% of general dealers and spazas had refrigerators, and only 13% (general dealers) to 14% (spazas) had freezers.

Third, store layouts lack the wide aisles of a modern store and have only simple shelves on the walls. These limitations make it difficult to use standard consumer packaged goods marketing techniques to optimize the display of products and brands.

Fourth, product and brand quality control is a problem in several consequential areas:

- Recalls. Too many products that should have been recalled remain on the shelf for sale. This creates health and safety risks for consumers, as well as cost and legal risks for sellers.

- Sell-by dates and spoilage. Selling spoiled, expired, or improperly stored products to consumers can pose health and safety risks and can damage brand reputation.

- Theft and counterfeiting. Customer shoplifting can limit the ability of shop owners to effectively merchandise or manage brand positioning. Fake or counterfeit products in some categories can be damaging to the real brands.

- Pricing variability. In the absence of supplier price-management support, a single brand or product category can frequently be offered for sale at a staggeringly wide range of prices. For example, we visited four stores selling the same brand of cornmeal, a South African staple, at R10, R12, R15, and R18 per kilogram—a spread that almost doubled the price between the least expensive and most expensive figures.

- On-shelf availability. Frequently, storeowners don’t have the particular products that customers are looking for because they have neither the working capital nor the storage space to guarantee availability. For FMCG companies, this problem often translates into a direct revenue loss, as one-person shops must either continue to operate with limited stock available in key categories or close entirely in order to stock up.

Multiple Benefits of Direct Relationships

We believe that the risks present in traditional channels, as outlined above, are manageable—and that the opportunities for FMCG companies to increase revenues, market share, and profits far outweigh the costs. By establishing and maintaining direct relationships and control in traditional channels, companies can realize a number of benefits:

- Superior Access to Forgotten Consumers. Traditional trade channels are widely dispersed across the country, with small shops in many remote locations. These areas offer the potential for companies to reach millions of new consumers who shop in traditional and modern stores. Potential buyers include people living in cites and rural areas who have access to transportation that enables them to shop in suburban supermarkets once a month but who would happily spend more in shops closer to home.

- Better Coverage and Leverage to Grow and Control Market Share. Access to a much larger customer base can lead to a deeper understanding of how to manage and target growth in promising and underdeveloped FMCG product categories and customer segments.

- More Targeted Advertising to Larger Consumer Segments. For all socioeconomic groups, brand activation is a very efficient way to increase sales. Companies that are not well represented in all channels and store formats can’t take full advantage of South Africans’ identification with brands. Targeted advertising builds brand awareness, loyalty revenues, and profits among discrete customer segments and across multiple product categories.

- Better Price and Quality Control. Many traditional stores stock their shelves with products that their owners have purchased from modern stores. As a result, those traditional stores don’t benefit from the business services and financial advantages that a direct relationship with FMCG companies could offer them, such as better trade terms, merchandising support, and direct-to-store delivery—all of which help drive a more profitable and scalable business model.

Investing in Traditional Channel Growth

Given the recent sluggish performance of South Africa’s economy and retail sector, this is a good time for FMCG companies to discover and unlock new growth through traditional trade channels. Already, we have seen several compelling examples of various companies seizing growth opportunities in these forgotten channels.

With regard to supply chain management, we are also seeing the emergence in South Africa of startup entrepreneurs who are trying to address fragmentation and access issues by becoming channel middlemen between consumer goods manufacturers and retailers.

Other consumer-facing sectors are seeing opportunities, too. A few South African banks are starting to experiment with using spaza shops as “bank shops” that offer minimalist, low-cost banking service as an alternative to full-service branches. The link to the bank’s back office is mostly via mobile phone. FMCG innovators should watch the progress of consumer banks as they begin to make digital payments and credit services available to small shops and their customers.

It is clear that as South Africa’s retail sector continues to modernize, traditional trade channels are poised to evolve in support of South Africa’s next wave of retail growth. Finding growth opportunities in both traditional and modern channels is a step forward for the country and for companies that can help make it happen.