In all industries, the need to cut procurement spending substantially and quickly is now paramount. But the inherent complexities of conventional methods—base spending cuts on categories and commodities—make it extremely difficult to get significant results rapidly.

A small number of leading companies have taken a radical approach. Instead of focusing on goods, they’re focusing on their suppliers. Segmenting their vendors into three groups on the basis of expenditures, companies are strengthening relationships with the suppliers that offer the strongest potential for savings. Companies that have deployed this approach are getting results. In many cases, they are seeing up to double the procurement savings in just three to four months. Here’s how they’re doing it.

A small number of leading companies have taken a radical approach. Instead of focusing on goods, they’re focusing on their suppliers.

The Problem with Conventional Procurement Methods

With an economic downturn looming on the horizon, the need for spending cuts has taken on new urgency. Given that direct and indirect materials constitute more than 60% of the typical manufacturer’s cost basis, procurement is an obvious place to look for ways to save.

Many companies maintain that it would be difficult to realize appreciable savings now because they have already optimized their procurement practices. To a certain extent, this is true.

Having put different people in charge of different tasks—for example, strategy people to develop the overall approach, commodity or category managers to direct the awarding of business to suppliers, cost estimators to provide a baseline to the category managers, operational buyers to take care of day-to-day purchase orders—companies have established efficient procurement efforts.

But these efforts are also quite slow to have an impact. Conventional practices are complex and time consuming, requiring analyses, preparation, negotiation, and implementation. Changing the procurement behaviors of dozens of executives responsible for purchasing commodities in various regions and locations can take many months. Even then, good results are far from assured, because suppliers bake future cuts into their original estimates.

Part of the problem is that organization structures are established to focus on commodities and categories, not suppliers. Additionally, many procurement systems can’t deliver basic information on what each supplier provides. Because some suppliers provide goods in many categories, it’s difficult to determine the full extent of possible cost-reducing opportunities. Making matters even more complicated and further hampering visibility, some suppliers operate through several legal entities with different names.

As a result, most companies can’t manage their suppliers satisfactorily. However, their suppliers—the leading suppliers, at least—have sophisticated account management practices for dealing with customers and maximizing margins proficiently. This asymmetry makes any kind of satisfactory customer-supplier relationship unsustainable.

A New Route to Cost Savings

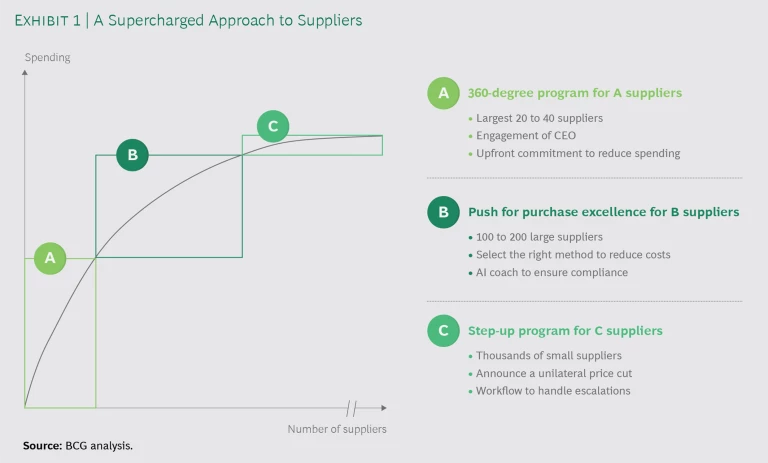

To remedy this problem and see substantial results fast, companies need to rethink all aspects of their engagement with their suppliers. We recommend taking a “supercharged” approach to suppliers, segmenting them into three groups on the basis of their spending. (See Exhibit 1.)

- Category A suppliers are the 20 to 40 companies that account for about 50% of a company’s procurement spending. These suppliers are asked to take part in what we call the 360-degree program.

- Category B suppliers account for about 35% of a company’s procurement spending. There are typically 100 to 200 suppliers in this bucket. This category of suppliers participates in what we designate the push-for-purchase-excellence program.

- Category C suppliers, in some cases numbering in the thousands, account for the remaining 15% of a company’s procurement spending. These vendors are included in the step-up-to-contribute program.

Taking a 360-Degree Perspective

The level of spending with A suppliers, both individually and as a group, is quite high, so companies must ensure that these suppliers will be willing to support whatever new plans are put in place. Therefore, the CEOs of customer companies must be responsible for managing these initiatives.

To ensure that the new approach gets off on the right foot, the buyer, or customer, CEO needs to have a vision for the relationship with each supplier. The CEO must define what the company wants each supplier to commit to upfront—typically doubling savings or cost-down performance over the next quarter or year—and what the company will commit to contributing in return.

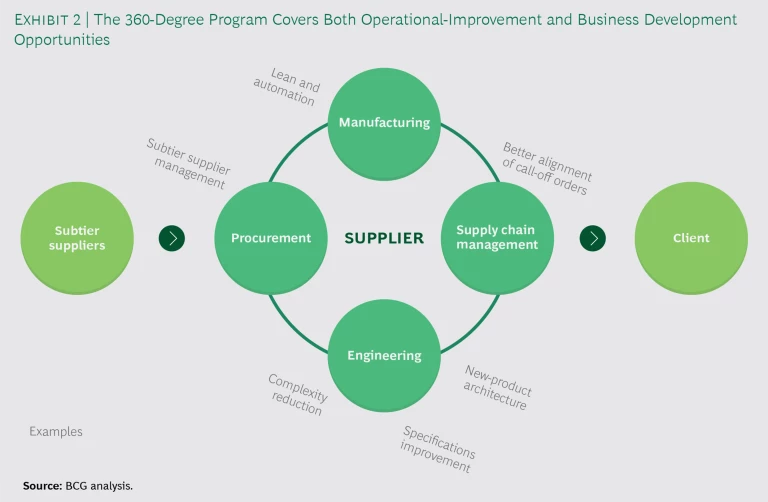

Continuing this initiative, the buyer CEO should reach out to the CEO of every A supplier, outlining the request and committing to helping the supplier in return. Carefully crafted and personalized letters have proved to work best, and they can be passed on by the buyer CEO internally. At the same time, the buyer CEO should invite each supplier CEO to suggest ways—operational or business development activities, including streamlining the sequence of deliveries and validating new technologies—for the two companies to work together to improve the supplier’s profitability. (See Exhibit 2.)

This approach shifts three conventional paradigms. First, it moves fundamental business decisions from the company’s operations managers to its top decision makers. Hemmed in by budget constraints and performance metrics, the supplier’s sales and account management people have little room to maneuver. But not its CEO. The supplier CEO will happily invest in a relationship with a customer if the opportunity is worthwhile. This works to the buying company’s benefit as well. The more time the supplier spends thinking about how to generate mutual benefits with a customer, the more likely it is that innovative ideas will result.

Second, the approach puts the supplier’s commitment to savings before the time-consuming analyses, preparations, negotiations, and implementation. More than simply reversing the sequence of events, this upends the long-held assumption that commitment to savings comes last.

Third, the approach challenges a commonly held supplier perception that procurement is a zero-sum activity in which the buyer aims to improve profits at the supplier’s expense. The buyer company needs to deploy every option available to help the supplier company, perhaps initially hurting the bottom line. The buyer company may have to spend considerable time helping the supplier figure out what kinds of initiatives would ultimately improve the supplier’s profitability. Regardless of what those initiatives might be, the customer company must follow through on this commitment—or risk losing the supplier’s trust.

The approach challenges a commonly held supplier perception that procurement is a zero-sum activity in which the buyer aims to improve profits at the supplier’s expense.

Given the magnitude of the request, not all A suppliers will be ready or able to commit to the 360-degree program right away. We’ve seen some suppliers quickly commit and suggest numerous ways that the companies could work together. Other suppliers, however, are at first reluctant to make an upfront commitment and do so only after extensive discussion. Still other suppliers are very hesitant and offer little in the way of constructive feedback. At some point, the buyer CEO needs to indicate that the company does plan to move forward with the program, leaving the supplier to choose to work with the buyer and grow profitably or cede to competitors. In our experience, about two-thirds of invited suppliers eventually sign up for the program.

Typically, a dedicated team is responsible for implementing the 360-degree program, and a joint buyer-supplier steering committee monitors it. The steering committee consists of the customer’s product development and procurement executives and the supplier’s key account managers and relevant functional executives, such as factory leaders for manufacturing-improvement initiatives. Once each quarter, the CEOs join the team meeting to keep everyone honest.

When the benefits of the program become evident, the buyer company should make them visible to suppliers that had not signed up in the first round. Chances are that they will scramble to be part of the second round.

Although the 360-degree program is largely operational in focus, it’s vital that the personal aspect not end after the negotiations are complete. With a view to overcoming roadblocks and taking the business relationship to the next level, the buyer CEO must continue to build personal relationships with supplier CEOs. Becoming a preferred customer can help a company gain access to innovations critical to competitive advantage.

Some suppliers quickly commit and suggest numerous ways that the companies could work together.

Pushing for Purchase Excellence

BCG’s program for B suppliers, the push for purchase excellence, starts by placing responsibility for each supplier in the hands of one procurement executive, whose task it is to make sure that the right cost reduction methods are deployed.

In many cases, this is the category leader who spends more than any other category leader on the supplier’s goods and would like that particular vendor to do well.

There are three types of cost reduction methods at a category leader’s disposal:

Technical-Idea Generation. This involves the identification of technical methods for reducing costs, such as concept tenders to eliminate unnecessary packaging and cost-out meetings with suppliers to eliminate services that are too expensive.

Commercial Preparation. These activities detect price reduction opportunities from suppliers with high margins. Should-cost analyses and linear performance pricing (LPP) are good examples.

Go-to-Market Approaches. These include opportunities—for example, face-to-face meetings, auctions, and large tenders—for negotiating with suppliers.

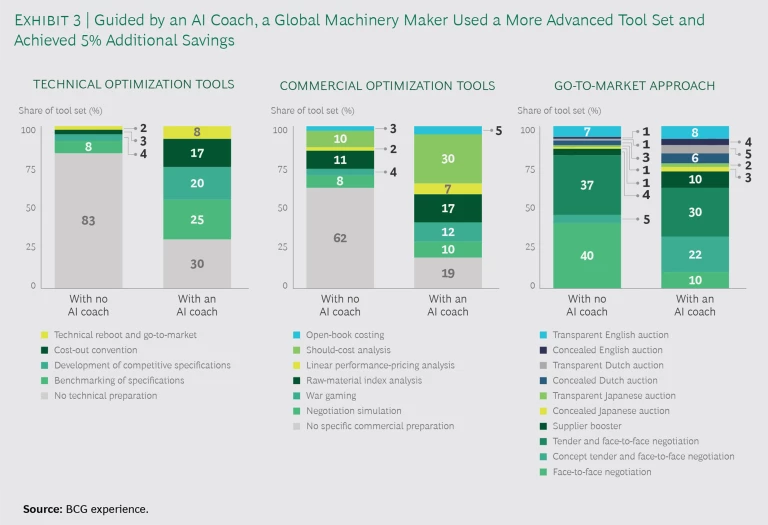

There are many different methods available, but most buyers use only a few of them—regardless of whether or not the results are satisfactory. This is explained in part by the fact that some of the methods—for example, LPP or auctions—are more labor intensive than others. But even buyers who don’t mind putting in the extra effort prefer using tools they know over those they don’t. As a result, companies rarely, if ever, deploy the right combination of cost reduction methods—and, therefore, pass up huge savings opportunities.

To address this issue, BCG developed the artificial intelligence (AI) “negotiation coach,” a tool that helps procurement employees select the best methods to use with each supplier. The coach begins by asking a series of questions to determine the key characteristics of the purchasing circumstances. Typical concerns include the number of suppliers available, their locations, the variation in their prices, and the extent of spending fragmentation. The coach then identifies the combination of methods that can generate the greatest cost savings. Any number of methods can be deployed in any combination.

Say, for example, a company is hiring a construction company to build a building. The coach might begin by recommending an internal cost-out workshop to identify strategies for boosting savings, including, for example, expensive noise-reducing features only on those windows that face the street and not on those that face a quiet courtyard. The coach then considers the supplier landscape. If different suppliers from Poland and Germany have similar pricing structures, the coach might recommend a so-called Dutch auction, which offers the best way to optimize savings while reducing the risk of collusion. (See Exhibit 3.)

The coach uses game theory to form the first recommendations. Learning which methods are the most effective in each particular situation, the algorithm adjusts its recommendations accordingly. The tool becomes increasingly proficient as it accumulates experience from each of the company’s buying situations.

Stepping Up to Contribute

Currently, companies are not generating much in the way of savings from most of their C suppliers. That’s because many C suppliers fly under the radar. They have never been on the receiving end of customers’ cost-cutting initiatives simply because most customers find it cumbersome to deal with so many unmanaged suppliers.

The step-up program that BCG created especially for such vendors, goes a long way toward addressing these issues. It increases the vendors’ visibility while making them contributing partners, like other suppliers.

The procurement executive who heads up the program, the “caretaker,” is given a target for reducing C supplier costs. The caretaker reaches out to C suppliers, asks for price reductions, and requests feedback within a certain number of business days.

To determine the exact percentage of the reduction, an AI-based, self-learning algorithm assigns weight to a number of parameters, including the supplier’s industry, location, size, profit margin, and share of the buyer’s total expenditure, as well as the last time the supplier reduced its prices. The algorithm also suggests the best communication approach. For some suppliers, a soft tone that emphasizes the contribution that they could be making is sufficient. For others, a harsher tone may be necessary.

The caretaker must also implement an escalation plan that spells out what to do if a supplier refuses to comply with the price cut or threatens legal action. It is possible to exclude suppliers that are, for example, innovative startups or at risk of bankruptcy.

For some suppliers, a soft tone that emphasizes the contribution that they could be making is sufficient. For others, a harsher tone may be necessary.

Making It Happen

The supercharging approach takes procurement back to its origins. It is a highly personal activity through which an executive of a customer company and an executive of a supplier sit down and hammer out a deal that their respective teams can execute.

This approach is unrivaled in its ability to achieve substantial savings in just three to four months. But there are certain imperatives to keep in mind:

- Understand the vital role of the CEO. CEOs don’t normally play a large role in procurement activities, so they need to prepare to champion such efforts, build robust bridges to the CEOs of A suppliers, and engage with those CEOs over the long term.

- Create a cross-functional push. Develop a broad, cross-functional effort that can help big suppliers become more profitable. And be willing to see through to the end any commitments the company makes to suppliers.

- Delegate authority. Procurement executives need to understand that they need to delegate authority. Delegating authority for A suppliers to the CEO is straightforward. Doing the same with peers for B and C suppliers is not. Executives may be concerned that they could lose control over the process or lose out to their peers.

Procurement executives need to understand that they need to delegate authority.

- Use the opportunity to make internal improvements. The program can provide many insights into the ways different functions work together, procurement’s role in the greater process, and opportunities for improvement. It provides a rare opportunity to create better structures, processes, and practices.

Encourage imitation of internal improvements. Everyone benefits if suppliers copy the program to get higher savings from and build stronger relationships with their suppliers.

This supercharged approach to suppliers is unrivaled in its ability to achieve substantial savings in just three to four months. But the long-term benefits may be even more powerful. By putting responsibility for success in executives’ hands, this approach can do much to build meaningful supplier relationships over the long term.