The rate of change in business today is so rapid that new products, technologies, and business models sometimes become outdated before companies can fully capitalize on them. Recent research by Boston Consulting Group suggests that only one in three companies successfully evolves in the face of industry disruption. Often, however, companies that do make the transition create even more shareholder value than they had before the disruption occurred. (See “Creating Value from Disruption (While Others Disappear),” BCG article, September 2017.) Why do some companies thrive in this environment while others fail?

Military history provides some insight. US Air Force Colonel John Boyd, a renowned military strategist, observed that some US fighter pilots in the Korean War had a far higher kill rate than others and were less likely to be killed themselves. Boyd’s analysis revealed that the ace pilots had faster OODA loops: they were able to observe, orient, decide, and act more quickly than their peers. By continually shortening their OODA loops, and thus increasing the tempo of the battle, they consistently caught their opponents off-guard. According to Boyd, when the loop is so fast and tight that a competitor’s response rate drops to zero, the opponent with the faster tempo has disrupted the competitor—and the end result is victory.

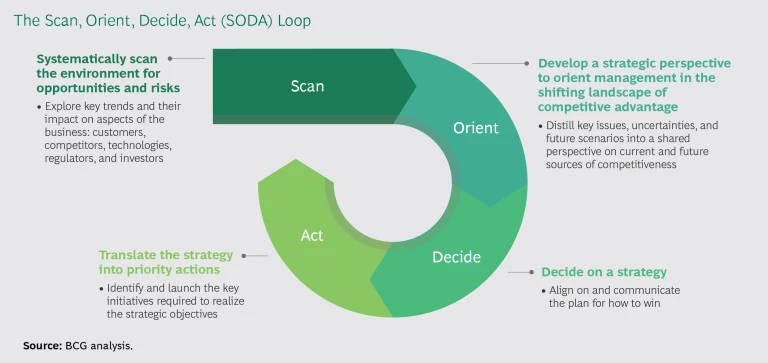

The same concept applies to today’s uncertain business environment. Disruptors—the most agile, responsive, and aggressive companies—put the squeeze on competitors with a similar dynamic loop. But since a solo pilot’s reaction time is unique to the circumstances and is far faster than an organization’s, we have adjusted the loop to better reflect that business reality. Our business version consists of four repeating aspects: scan, orient, decide, and act (SODA). Disruptors continually scan the landscape, orient themselves to new circumstances, decide how to respond, and act quickly. (See the exhibit.) Then they regroup and repeat the process. With experience and expertise, their SODA loop tightens and their tempo accelerates.

A tempo advantage relative to the competition is the best long-term insurance against being disrupted. In any sector, the company that sustains the fastest cycle time usually wins. We call this rapid, continuous cycle tempo-based competition.

To illustrate how the SODA loop works, let’s examine each of the four aspects more closely:

- Scan. Since competitors, technologies, and markets can change quickly, companies must systematically scan the horizon for new opportunities and for potential disruptions. Scanning broadly is crucial, but so is focusing on factors that could undermine or strengthen key profit and value drivers, such as trend lines, new customer behaviors, anomalies, unexpected competitors, shifting customer economics, and changing demand patterns. For key megatrends, organizations should look for tipping points signifying that a new trend or technology is gaining traction. For instance, new price, performance, and adoption thresholds of component technologies—which were visible to all who were keeping track—preceded the explosion in global demand for robotics. Data analytics can be a great source of input for scanning. China’s Alibaba, the massive online marketplace, continuously scans customer behavior patterns, analyzing more than a petabyte of customer data every day. By scanning the landscape nonstop, companies are able to maintain an external focus and avoid the surprises that come with complacency.

By scanning the landscape nonstop, companies are able to maintain an external focus and avoid the surprises that come with complacency.

- Orient. The orient phase is about connecting the dots to understand what all of the strong—and weak—signals observed in the scanning process actually mean. Are sources of competitive advantage shifting? Are existing profit pools drying up and others forming? Which broad value propositions and business models are winning? How are the needs of target customers changing? Where are the greatest opportunities and risks? What are the most plausible scenarios for how the sector will evolve, and what potential “black swans” may be lurking? The goal is not to set the strategy, but to develop a broadly shared map of the landscape—an understanding of where the organization and its rivals are situated, where treasure may be buried, and where quicksand awaits the unwary. Effective orienting requires a diverse leadership team that can continuously analyze different scenarios, discuss and realistically evaluate the choices that are available, and look beyond the obvious to envision opportunities and risks that may lie beyond the horizon.

- Decide. This phase involves defining and communicating the organization’s broad strategic intent. What position(s) in the landscape does the organization want to own—and at a high level, how will it get there from its current position? Who are the target customers? What value proposition will help win them? And what, if any, broad changes in operating model are necessary to support the strategy? In the interest of speed, these decision points require not granular plans but clear choices about strategic direction, customers, and value chain presence that can direct and empower teams throughout the organization to bring the plan to life. Because the teams are already oriented to the playing field, they can make smart, aligned decisions and help spot signs of changing conditions.

- Act. Maintaining a suitably rapid tempo requires swift execution of strategy. Throughout the organization, teams define and test the tactics that they believe are most likely to realize the organization’s strategic intent. Then, on the basis of experience, they adapt their tactics to better realize the organization’s objectives. To ensure alignment and fast action, leaders must explicitly link individual and team missions to the company’s overall mission and strategy. Any incongruities among goals, resources, and constraints must be identified and flushed out early, to minimize wasted time and effort. For instance, Zappos—the online retailer of shoes and more—has identified one overriding mission: to make its customers happy. The company’s service reps know that they are authorized to do whatever it takes to achieve that goal, without having to get approval from their superiors. So they will refund defective products and replace them for free, send flowers to a customer’s sick mother, and spend as many hours on the phone as necessary to resolve a problem.

Maintaining a suitably rapid tempo requires swift execution of strategy.

One hallmark of tempo-based competitors is their ability to move more and more quickly through the four steps of the SODA loop as they accumulate learning and experience. In a broader sense, the SODA loop describes the process of scaled learning on a company-wide level.

In a sense, the SODA loop describes the company-wide process of scaled learning.

Market leaders stay ahead of the pack—and keep the competition guessing—by constantly changing and improving key aspects of their value proposition and operating model. Ralph Hamers, the CEO of ING, put it this way: “Don’t wait for new players or incumbents to compete with you, disrupt you, or disrupt your model. You take the lead. If you feel there’s an opportunity to disrupt and change your business model, do so. It’s very hard to make this decision as a manager or a leader because, basically, you’re cannibalizing your own business.” (See “Ralph Hamers on Disrupting the Banking Industry,” BCG interview, September 2016.)

Quicken Loans offers a perfect example of this aggressive strategy in action. Once a traditional mortgage provider, the company shifted its focus to online in the late 1990s. Through its online arm, Rocket Mortgage, Quicken Loans makes the mortgage process easy for the average consumer to understand. As of 2018, Quicken Loans was the largest home lender in the US.

Most companies spend far too much time on things that slow people down, consume resources, and add little value. Tempo-based competitors such as Quicken Loans, Alibaba, Amazon, and Zappos understand that the best way to avoid disruption is to maintain an unwavering focus on the factors that confer a competitive advantage—and to never stand still. Stationary companies become targets.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.