Urban transport is about to move in a radically new direction. On-demand and shared mobility services are already offering people greater choice about how they travel. The rise of travel apps has made software companies key players in urban transport ecosystems. In tandem, private investment in new mobility operators, including those that offer ride-hailing and free-floating services, is accelerating—witness SoftBank’s $1.5 billion investment in Grab and Honda’s $2.8 billion partnership with General Motors’ Cruise—reaching record highs over the past 12 months.

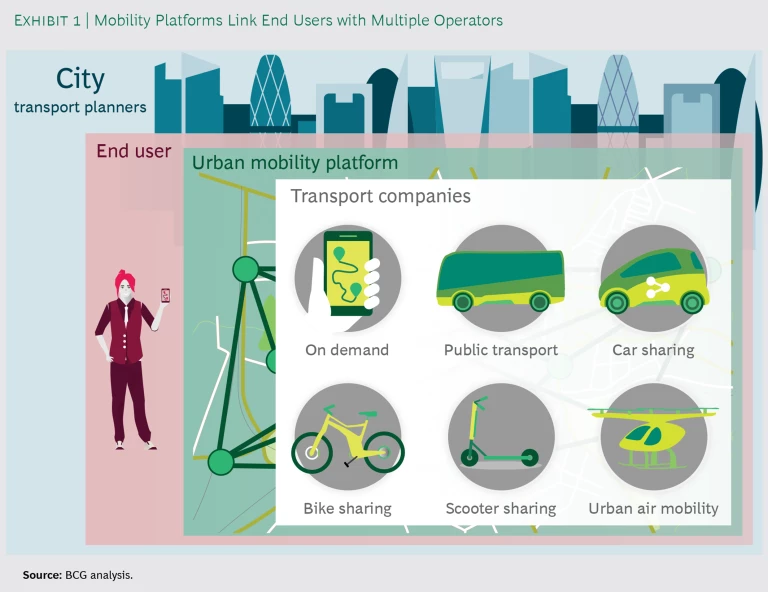

Despite this flood of money into single-modal offerings, digital intermodal platforms that help users coordinate travel across multiple modes are likely to be the next game-changers in urban transport. (See Exhibit 1.) By linking different mobility options together via a single customer interface, these platforms provide a personalized, optimized service while capturing valuable information about users’ travel choices. And though still at an early stage, they will eventually overtake today’s hot investments. Such platforms will also enable the shift from personal vehicle ownership to mobility as a service .

Realizing these benefits will demand the cooperation of all players in the mobility ecosystem , including city mobility planners, mass transit operators, and software companies. Several types of players are competing to become the future leaders in this new field, and it’s not clear yet which will come out on top. Our experience in the sector suggests that it takes multiple factors to win. Organizations that excel at all of them will move much closer to monetizing their platforms and establishing market dominance in the long term.

Urban Mobility to Come

User rates for urban mobility platforms linking different types of transport are still low compared with single-mode mobility apps such as Uber and mytaxi, but that could change rapidly. A variety of organizations are actively developing these platforms. They include software company Transit in the US, London-based startup Citymapper, ReachNow (a joint venture of Daimler and BMW), and Deutsche Bahn’s Mobimeo platform—and these are just the tip of the iceberg. Having disrupted traditional cab services over the past decade, Uber and rival ride-sharing company Lyft are now expanding into new forms of transport, a significant first step in developing an urban mobility platform.

Public- and private-sector organizations are realizing that owning the interface between users and other members of the urban mobility ecosystem will be the key to creating future value. Platform providers will have greater access to customers and their data and will benefit from stronger brands than those of other stakeholders. As the market evolves, we expect regional urban mobility platforms to emerge. Other mobility providers will join in order to keep their offerings relevant and gain access to the customers afforded by these platforms.

The data generated by users and aggregated by urban mobility platforms will enable cities and other stakeholders to improve demand forecasting, combine innovative technologies (such as bike and scooter sharing) with existing transport systems, and provide an ever more seamless consumer experience. More information about the travel patterns of individuals and vehicles will allow cities to manage traffic flows better, lower emissions, forecast infrastructure needs accurately, and plan transport-related construction and maintenance work so that they minimize disruption. Logistics companies will be able to provide last-mile fulfillment services more effectively—by delivering during off-peak hours, for example.

In order for these scenarios to be actualized, multiple transport operators will need to migrate to urban mobility platforms. We expect successful and sustainable platforms to perform at least five functions, which will allow them to gain widespread acceptance among both users and operators.

- Personalized Travel Planner. Platforms will supply individualized travel options based on real-time information, optimizing across transport modes for factors such as time, cost, and comfort. This functionality is already a standard component of urban mobility platforms today.

- Intermodal Ticketing and Pricing. They will consolidate different fare schemes, such as pay as you go, prepay, and monthly subscriptions, and integrate the online ticketing engines of different mobility operators onto a single platform. As a result, they will provide users with bundled travel options, combining two or more stages of a trip into one fare. It is this ability that differentiates a true urban mobility platform from a single-mode mobility app.

- Real-Time Passenger Information. To keep users informed of accidents and delays and help them avoid congestion, platforms will provide passenger updates in real time, with details of incidents, infrastructure and maintenance work, and changes to recommended routes.

- Troubleshooting Customer Services. Customers will need to access round-the-clock support via their mobile devices when they encounter difficulties with payments, ticketing, or a specific mobility operator.

- Location-Based Services. Platforms will offer location-based services that add value for users, such as localized restaurant recommendations or information about nearby events. While not a defining characteristic of an urban mobility platform, such services will likely be necessary in order for organizations to monetize their business models.

Challenges Ahead

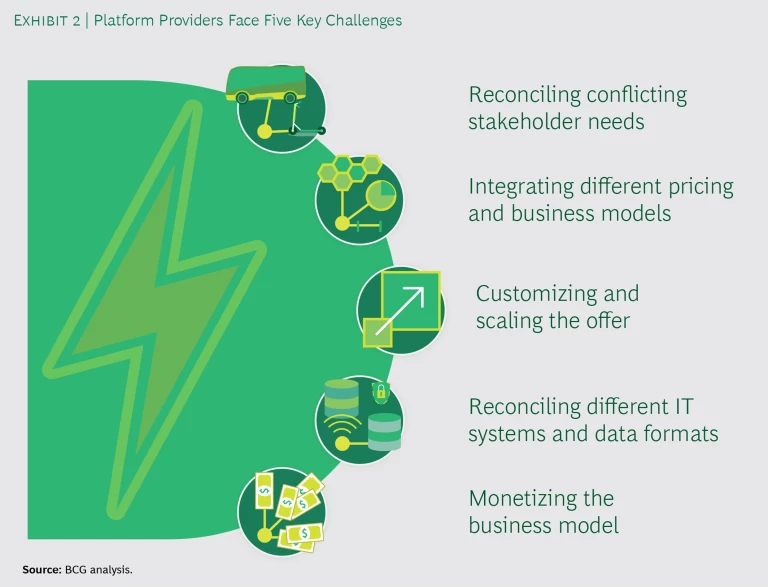

Platform providers will have to overcome five key challenges if they are to achieve these functionalities. (See Exhibit 2.)

- Reconciling Participants’ Requirements. Urban mobility platforms operate at the center of a complex and evolving ecosystem of participants. Each has separate needs, and there is potential for conflict. For example, many mobility operators want an exclusive user interface. And while city planners seek to optimize public transport, innovative solutions typically aim to disrupt incumbent operators. Providers of urban mobility platforms need to find ways to resolve these conflicts.

- Integrating Mechanisms and Models. Providers must consolidate different pricing and business models onto their platforms. These vary widely. While some mobility operators set fares based on distance traveled, others rely on factors such as time and demand or use a zonal approach to pricing. Platforms must integrate these various mechanisms in order to provide users with a single, intermodal fare. Providers must take into account legacy business models based on fixed schedules and stations, as well as new and innovative models, such as on-demand and free-floating services. They need to handle a raft of discounts and subsidies aimed at different ways of traveling or specific consumer groups.

- Customizing and Scaling the Offer. To be profitable, providers must customize their urban mobility platforms for local users and operators, while also replicating them in other cities. This is a difficult balancing act. Platforms need to work at the local level, dovetailing with a city’s infrastructure and the existing mobility ecosystem. They need to reflect local rules, regulations, and policy decisions—about fare subsidies, for example. But providers must be able to use the same software components and IT architecture across multiple cities if they are to achieve economies of scale, attract large, regional mobility operators, and add customers quickly and cheaply.

- Consolidating IT Systems. At the operations level, providers face the difficult task of reconciling different IT systems and data formats. There are two reasons for this. First, they face myriad legacy systems that have been developed by operators and government agencies to handle distinct mobility and pricing models. Second, data such as timetable information can vary significantly in format from one player to the next, creating a major headache for platforms seeking to make systems mutually compatible.

- Monetizing the Business Model. Finally, urban mobility platform providers must figure out how to make money. Ride-sharing services and other new providers use an array of approaches to monetize their offerings—all of which have drawbacks for platform providers. For instance, charging end users for access to the platform poses significant difficulties. Unless the offering is compelling (which depends on the provider and the mobility operators on the platform) or includes value-adding elements such as location-based services, end users will likely opt to purchase tickets directly from individual mobility providers in order to avoid any extra fee. Equally, levying a per-journey commission on mobility operators would erode their already thin margins and could persuade them to develop their own digital solutions.

When it comes to approaches that rely on the public sector, generating worthwhile revenues from a white-label urban mobility platform (developed by a private company and bearing the city’s brand) through a license fee arrangement could be hampered by a shortage of city funds; it might also hinder platform providers from establishing a strong market position at the required speed. But reliance on value-adding services—analyzing users’ travel information for public entities seeking to improve their transport policies or infrastructure planning, for example—would require platform providers to build data analytics capabilities. This strategy could also be derailed by data privacy issues.

What It Will Take to Win

We believe that successful urban mobility platforms will meet these challenges and thrive by executing on the following five fronts. (See Exhibit 3.)

- Focus on users. Successful platforms won’t compromise in their ambition to meet users’ needs. They will make urban mobility as simple and convenient as possible by offering a smart and seamless end-to-end travel experience. As they evolve, they will become increasingly sophisticated. To succeed over the long term, providers will need to combine every aspect of platform functionality in a fully integrated offering with a superior interface, so that users can plan their journeys, access fares from different transport operators, and purchase bundled mobility packages.

- Adopt an impartial stance. Platform providers will need to act as unbiased brokers if they are to prosper and gain the support of municipal authorities and mobility operators. They will treat public transport as the backbone of urban transportation and integrate private-sector mobility offerings impartially, while considering such factors as time, price, convenience, and congestion.

- Customize for local stakeholders. Platform providers will tailor their offerings to local requirements by using a city’s branding and adapting to its transport systems and regulations. Winning platform providers will take account of variations in mobility options, business models, and operating standards from one city to the next.

- Facilitate scaling. Providers will adopt a standardized, modular approach to IT so that their offerings can easily be scaled up in new locations, and they will deploy cloud-based IT architecture, rather than localized solutions, that can be replicated elsewhere. In the future, the market is likely to be dominated by a small oligopoly of players, which could allow customers to use the same log-in for multiple platforms within a single region.

- Use an open approach to IT. Providers will build an ecosystem of partners, using common APIs (application programming interfaces) and keeping barriers to entry low to encourage mobility operators and other stakeholders to join. They will also foster data sharing among participants to maximize the benefits of the ecosystem approach.

It’s hard to make money today in urban mobility platforms. The Holy Grail—a successful common approach to monetization—has yet to emerge. Some providers, such as Whim, are experimenting with a subscription-based model, enabling city dwellers to pay in advance for different types of transport. Others are integrating advertisements with the user interface, even though this risks compromising the user experience. Still others are actively exploring how to license platforms as a white-label software product or to monetize the potentially valuable data that they generate.

Many players are willing to put monetization on hold for now as they focus on strengthening their core offerings. New mobility operators, such as ride-sharing firms, are spending on better functionality for their apps—a first step in the creation of a platform—to attract more customers to their main business. Meanwhile, legacy providers, such as mass transit operators, are also investing in functionality to protect their existing customer interfaces and ensure that they remain relevant for end users. Both groups provide opportunities for software companies that can provide this functionality.

Over time, a sustainable platform model will emerge, driven by an organization able to forge the necessary partnerships between different players and meet the needs of both the private and public sectors. Fully integrated platforms will have additional functionalities, including the distribution of subsidies and discounts that incentivize travel via environmentally friendly transport options or at off-peak hours. By performing this function for the public sector, platform providers will achieve real success and economic sustainability.

Different players are likely to dominate the development of urban mobility platforms in different regions. In some locations, cities and public authorities will take the lead; in others, private operators will win the race for market dominance. (In a subsequent article, we will examine the different ways in which urban mobility platforms are likely to develop in China, Europe, and the US and which types of organization are likely to succeed.)

By meeting the requirements of end users, city authorities, and public and private transport providers, urban mobility platforms will be at the center of urban transport systems. But coming out on top won’t be easy. To flourish, platforms must offer comprehensive and integrated functionality, particularly in payment and ticketing systems. They also need to act impartially with all stakeholders. In this way, they can ensure that their offerings benefit end users while also providing advantages for other players in the mobility ecosystem—including cities, which are set to play a far bigger role in shaping urban transport. The organizations that achieve these and the goals above, ahead of the competition, will be well-placed to emerge as winners.