Depending on one’s perspective, the media industry is a highflier, a somewhat fading sector, or a real stinker. The strongest performers have clearly uncovered a winning formula. Five of the top ten value creators in BCG’s most recent survey of the TMT sector overall are media companies taking advantage of rising media consumption. But other companies are not faring as well. The industry fell eight spots in our 2014−2018 rankings from the prior period (2013–2017), to 12th place. Median annual TSR dropped more than half, from 22% to 9%.

The industry’s worst performers have had an especially tough five years. Seventeen companies, more than a quarter of the sample, generated negative TSR, and three of those had been in the top ten as recently as five years ago.

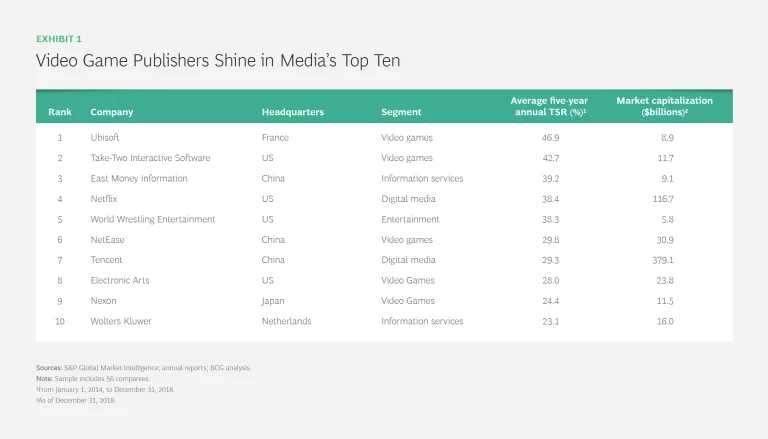

What’s also noteworthy is that the top-performing companies in the industry are not traditional news or entertainment media companies. Five video game publishers, including the top two performers, Ubisoft Entertainment of France and Take-Two Interactive Software of the US, made the top-ten list, as did three companies from China—a game publisher, a financial services information provider, and online giant Tencent. (See Exhibit 1.) Just five years ago, on the other hand, seven of the top ten performers were more traditional media companies, such as ProSiebenSat.1 Media, a German broadcaster and pay TV provider; CBS, a US broadcaster; and Schibsted Media Group, a Nordic newspaper publisher.

While the names may have changed, the top performers have figured out an old-media lesson. Subscriptions and recurring revenues pay. Until cord cutting took hold, cable networks and operators relied on the one-two punch of ads and subscriptions to become cash flow machines. Newspapers played a similar card.

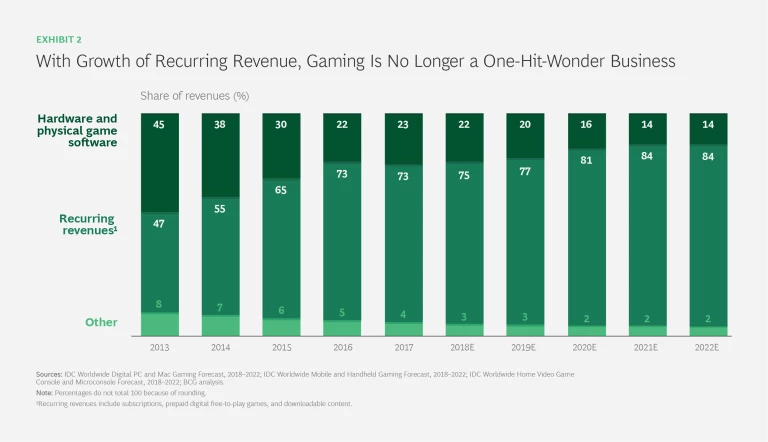

Game publishers have traditionally relied on unpredictable sales of individual software titles rather than ads. In recent years, they have matured from this hit-driven model to more sustainable businesses. (See Exhibit 2.) Nexon, the number-nine media value creator and a new member of the top ten, has relied on recurring revenue from consumers since its inception. The other four gaming companies in the top ten, which were top-ten performers in 2013–2017 as well, reported big boosts in revenue from in-game spending and other forms of recurring revenue.

Perhaps the most noteworthy transition away from the hit business may be the 5th-ranking media value creator, World Wrestling Entertainment. In 2014, the purveyor of pro wrestling created the WWE Network, a $9.99-per-month streaming service that supplements its popular pay-per-view events. Among similar sports services, WWE Network is second in size only to baseball’s MLB.tv . Growth in subscribers and recurring revenue have contributed to its attractive current multiple. (Likewise, Netflix, the number-four media value creator, generates nearly all its revenues from subscriptions.)

Although they landed outside the top ten owing to shifting investor sentiment and regulatory pressure, Google’s parent company, Alphabet, and Facebook deserve special mention for their leading shares in the digital advertising market. (In absolute terms, Alphabet and Facebook were the source of nearly half the media sector’s $1.2 trillion in value creation over the most recent five-year period.) They are expected to account for 48% and 39%, respectively, of the growth in digital ads from 2016 to 2019. Spending on digital ads will likely surpass spending on traditional ads by 2021, when ad buyers expect Amazon to be a growing force. A survey of 50 senior US advertising buyers in late December suggested that the company could double its US ad revenue from top ad buyers in the next two years and reach a 12% share of the digital ad market.

Reinvention, Now or Never

The message is clear. Traditional media companies need to reinvent themselves, and they need to do it purposefully and aggressively. As a necessary first step, they must become more aggressive in cost cutting. This will give them the breathing room to manage the decline in their traditional business and the headroom to invest in high-ROI areas.

Traditional media companies need to reinvent themselves, and they need to do it purposefully and aggressively.

As print media publishers discovered when classified ads declined in the dot-com era, once-successful business models can evaporate swiftly. Broadcasters, cable operators, and TV stations have not yet experienced an equivalent decline, but the signs are ominous.

Over the next five years, approximately $30 billion in profits could shift away from broadcast and cable networks, TV stations, and operators in the US. Studios, rights holders, and a galaxy of streaming companies, such as Netflix, will be the winners in this changing landscape. This shift is pushing broadcasters and cable operators to try to hold onto their customers and profits with direct-to-consumer streaming services. But these efforts will not be any easier once Disney, with its huge catalogue of hits, launches its own streaming service in late 2019.

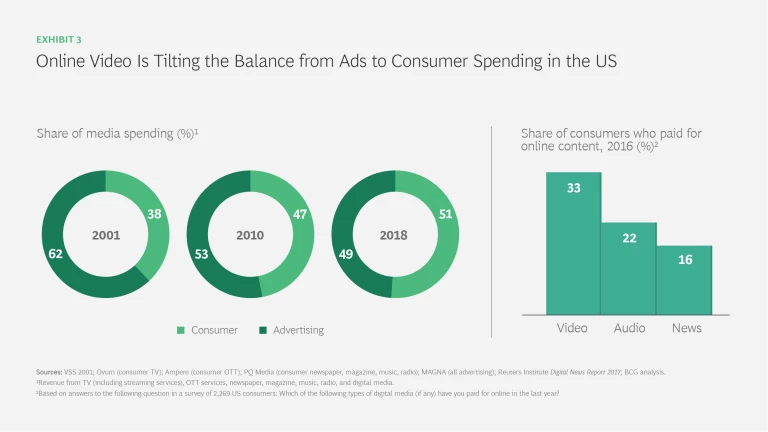

Collecting money from consumers is easier for some companies than for others. US media companies now collectively take in more money from consumers than from advertisers. But consumers have shown a much greater willingness to pay for video or audio content—through Netflix or Spotify, for example—than for news. (See Exhibit 3.) That helps explain why traditional news organizations have rarely appeared on our top-ten lists in recent years. Others have been making progress, however. The New York Times, for example, has more than 3 million digital subscribers; by the end of 2018, despite the market selloff, the company’s stock had doubled from its low in October 2016.

Digitization and AI-Enablement of Value Chains

Reinvention will require media companies to take full advantage of technology and digitize their value chains. As part of this reinvention, AI will eventually play a critical role along the entire value chain, from content creation and development to advertising effectiveness and viewer engagement. For example, 21st Century Fox is using machine learning to analyze movie trailers frame by frame in order to predict what types of films viewers will want to watch, while traditional news organizations have been experimenting with the use of both AI and robotic process automation to improve content creation and operational efficiency .

Reinvention will require media companies to take full advantage of technology and digitize their value chains.

These examples only scratch the surface. In China, Baidu has used AI to create customized ads for different types of car buyer . For example, ads can be tailored around performance, luxury features, or safety. In the near future, AI will go beyond segment-of-one marketing to create messages based on specific context—ads served during family time on a Saturday afternoon would be different from those served during work on a Monday morning, for example. Eventually, generative adversarial networks, which are essentially dueling algorithms, will create content such as background music, basic journalism, and video with barely a “human in the loop.”

In the meantime, media companies have more basic blocking and tackling to do in combining their digital and traditional sales forces and their online and print newsrooms, or in updating out-of-date marketing technologies. In the understandable rush to create new capabilities and functions, some media companies have created digital centers of excellence or standalone units that they are now integrating into their organizations. One of the leaders in addressing these issues is The New York Times, which has periodically publicized its efforts to bring the organization into the digital age.

The media industry is poised at a crossroads where young companies are borrowing the subscription lesson from old companies and traditional companies are attempting to modernize their organizations and their approach to audiences. While the young are on top at the moment, industry leadership is never assured. The winners over the next five years will likely be a combination of successful disruptors and those that have been most successful at rejuvenation.