As digitization and the Internet of Things (IoT) make homes, phones, and cars increasingly “smart,” corporate partners are beginning to work together in order to create interconnected offerings that are proving more valuable than a single company’s isolated product or service. These digital ecosystems are often orchestrated by market share leaders and are quickly reshaping a wide array of industries , such as consumer products, health care, and automotive.

From Alexa and Siri to Philips Digital Healthcare to BMW’s and Volkswagen’s connected-car ecosystems, the race is on to meet new customer needs through the use of digitally enabled collaborations. Although excitement about digital ecosystems is growing , executives still don’t fully understand what makes a particular digital ecosystem successful. To shed light on this topic, Boston Consulting Group gathered data and interviewed industry experts to discover what separates digital ecosystems that work from those that don’t.

It turns out that measuring ecosystem success is surprisingly difficult. Participants don’t have separate accounts or neatly delineated analyses of performance. We chose to focus on three metrics: financials (the orchestrator’s revenue and growth, narrowed down by business unit when possible), innovation (ecosystem-related patent data normalized for orchestrator revenue and employee numbers), and total users and growth (based on company and press reports). Using this quantitative data, as well as qualitative data derived from interviews, we studied 44 digital ecosystems in 12 sectors to understand what drives success, as seen from the perspective of the orchestrator.

Five Digital Ecosystem Success Factors

So, what do those who aspire to orchestrate these digital ecosystems need to do—and how can partners choose the right ecosystem to join? Our results reveal five factors common to successful digital ecosystems.

A Fast Start Is Not Enough

Because many digital ecosystems are also platform businesses , the emphasis is on being first, or at least early. The received wisdom is that scale begets interest, which begets scale, leading to winner-takes-all markets.

But our data shows that being an early mover is not sufficient to ensure long-term success or dominance, for several reasons. First, the ecosystem’s product or service may simply not be suited to some customers’ needs. Second, as technologies and customer needs evolve, later entrants can jump in and take advantage. And third, in their haste to be first, early movers sometimes build the wrong ecosystem or choose the wrong path. Consider how Symbian, an early mobile operating system, plummeted from a 70% market share to bankruptcy as it took wrong turns and lost the confidence of its partners.

Our data shows that being an early mover is not sufficient to ensure long-term success or dominance.

In other words, long-term success depends less on being the first mover and more on taking the time to craft the right strategy and value proposition and to attract the right partners. Many of the most successful ecosystems we studied were second or even third movers but still had no shortage of willing partners. For example, in the smart-health space, latecomer IBM Watson didn’t start building its own ecosystem until 2014—yet it had developed an ecosystem of 53 partners by 2017. That explosive growth was thanks in part to an automated and streamlined onboarding process; partners could join rapidly, and the ecosystem scaled fast.

A Strong User Base

While being early may not help much, having a robust user base certainly does. We found that, in most cases, the more successful ecosystems were orchestrated by an established market share leader. These leaders were best positioned to attract partners with the right skills and funding.

This is important insight for those looking to join a successful digital ecosystem but also for existing industry leaders. The idea of starting a digital ecosystem might seem far-fetched to some large incumbent players, many of which are used to going it alone—either by trying out new things in-house or by simply acquiring innovators. But it’s better for them to shape the new digital landscape , especially since they have advantages that rivals just can’t match, most notably a strong user base.

A Deep Bench of Partners

Many ecosystems need to bring in expertise from other industries. Our research shows that 83% of digital ecosystems involve partners from more than three industries and 53% from more than five. For instance, to bring an advanced robotic vacuum cleaner to market, a household-electronics manufacturer might partner with sensor and camera manufacturers and an artificial intelligence software provider, as well as with technology research facilities.

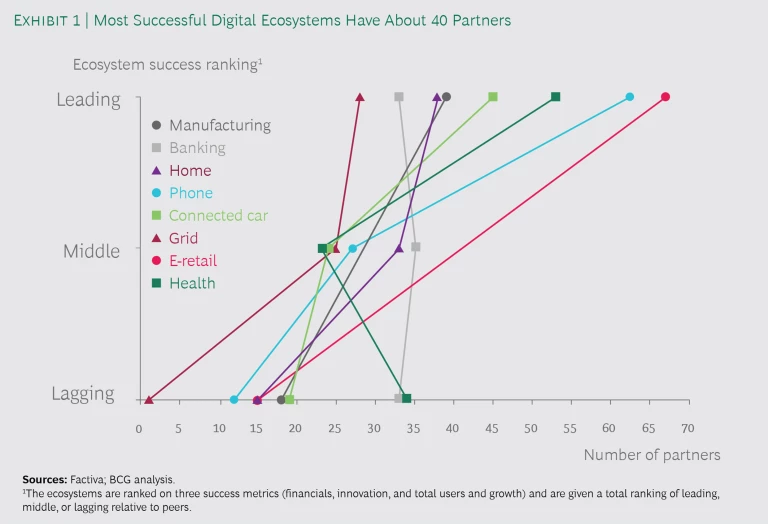

In fact, our analysis suggests that the more partners an ecosystem has, and the more industries they come from, the better that ecosystem will fare. While the average ecosystem has 27 partners, the most successful digital ecosystems have about 40. (See Exhibit 1.) Amazon, for example, has 67 core partners according to our analysis—roughly double that of its peers in e-retail—spanning logistics, finance, media, and telecommunications. Such a diverse group of partners inevitably leads to some misaligned expectations and some corporate-culture clashes. But orchestrators can’t just duck these challenges. Success clearly depends on the scalability and flexibility to bring in partners from a broad variety of industries.

A Big Global Footprint

Another characteristic of success is geographic scope. Successful digital-age partnerships require remote collaboration across geographic, language, and cultural barriers. Our analysis shows that 90% of ecosystems involve participants from more than five countries, and 77% of ecosystems span developed and emerging markets.

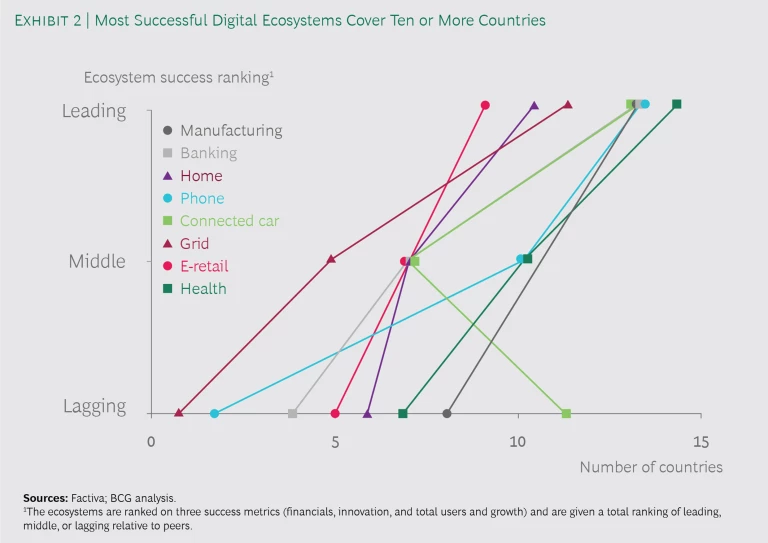

As with the total partner numbers, it seems that the wider the geographic reach, the better. (See Exhibit 2.) On average, successful digital ecosystems have partners in 10 or more countries, while typical ecosystems have just 5. For example, Ant Financial, which ranked highest among financial services peers, has core partners in 13 countries in the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Australia. These cross-border partnerships have been instrumental in satisfying Ant’s core Chinese consumers, who want to use payment apps while traveling abroad.

This doesn’t mean that locally focused ecosystems have no role to play. In fact, our analysis points to a few dominant, global ecosystems that coexist with localized ecosystems that scale up more slowly. But global reach is strongly correlated with success.

A Robust Collaboration Capability

The orchestrator of a winning ecosystem must manage dozens of partners, across multiple industries and countries, and different types of relationships (for example, contractual agreements, platform partnerships, and minority shares in venture capital investments). Selecting and managing the right mix of collaborations is critical for success.

Selecting and managing the right mix of collaborations is critical.

Consider medical technology. In the past, a health care solutions provider and medical-technology original equipment manufacturer (OEM) would typically form a bilateral alliance. Today, we see digital webs of relationships comprising 25 or more interdependent partners from multiple industries and countries, linked by anything from contracts or joint ventures to minority investments or full mergers and acquisitions (M&As).

The automotive sector has been undergoing similar changes as it explores connected and autonomous driving. To deliver an integrated, digitally enabled solution, automotive OEMs are evolving from supply chain controllers to orchestrators. They oversee the ecosystem, define the strategy, and identify potential participants.

Arrangements like these give an ecosystem more flexibility and the ability to experiment as it responds to changing customer preferences, new technologies, emerging competitive threats, and regulatory changes. Our research shows that 90% of digital ecosystems include three or more deal types. But flexible deal types also demand an approval process that is different from what’s used in traditional contracting and M&A—one that’s faster, leaner, and closer to the business.

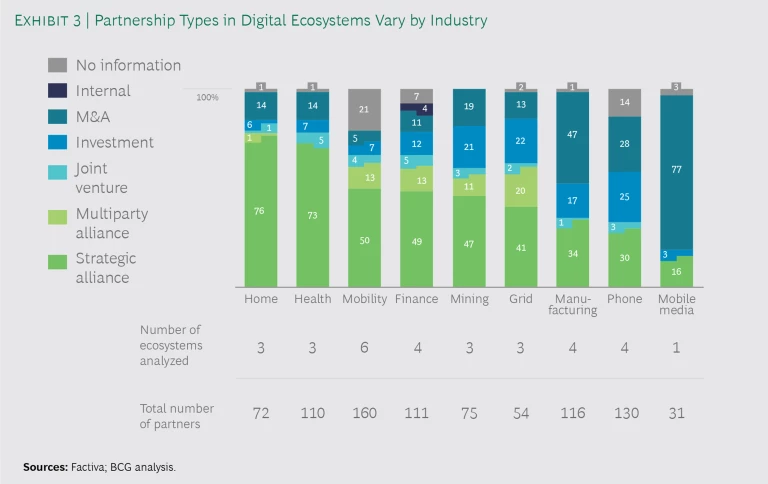

Our research also shows that each industry leans toward its own unique mix of partnership types—and it’s helpful for orchestrators to understand which combination works best in their sectors. (See Exhibit 3.) For example, among rapidly developing consumer-facing businesses, such as smart home and smart health, collaboration structures tend to be looser. Ecosystems need a wide variety of contributors and skills, and it’s also important to experiment with different partners without making large capital outlays. B2B companies, meanwhile, tend toward tighter control through closer deal types.

Individual company strategy plays a part in what type of partnership mix is appropriate, however. Apple—though consumer-facing—is known for tightly controlling information and quality in order to limit brand risk. BCG’s future research will look more closely at when particular types of agreements work, when they don’t, and what is the most effective configuration.

Winning in a World of Digital Ecosystems

An excellent example of these five success factors coming together is Amazon’s Alexa. It was the third mover in its space, not the first. It’s owned by Amazon, the largest e-retailer with a 49% share of the US e-commerce market, according to eMarketer. And Alexa has linked up with more than 38 core partners according to our analysis—10 more than the smart-home average—and those partnerships span four continents and 11 countries, also far above the average. Finally, Alexa focuses mostly on looser alliances, boosting its flexibility and ability to add value.

Of course, correlation does not imply causation. Maybe it comes down to an unusually compelling value proposition, whose appeal attracts complementary partners from so many market segments and countries. Yet the top ecosystem orchestrators in our sample, like Alexa, didn’t start by being superior; their strategy made them winners. And, while the exact reasons for any one ecosystem’s success can be debated, it is clear that digital ecosystems are quickly forming and reshaping industries across the globe, changing the very nature of collaboration and value creation.

Until now, much of the discussion in the marketplace has focused on describing the structure and workings of ecosystems—but that’s not enough. Orchestrators must understand how to make their digital ecosystems succeed, while potential partners must know what to look for when considering which digital ecosystems to join. We believe the five characteristics described here give executives a sound foundation for making these judgments and put them in a strong position to collaborate profitably in a rapidly evolving business environment.