Work, wrote the oral historian and master of social insight Studs Terkel in 1974, is about a search “for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying.”

Almost half a century later, the nature of work for many of us has changed for the better, and the ease of changing jobs when we are unhappy has improved as well. But the search for daily meaning, recognition, and astonishment continues. People want their jobs—and their companies—to have meaning, and they look to their companies’ leaders to define clearly what outcomes they are trying to achieve. Many leaders try to provide such clarity, of course; but as companies become bigger, more complex, and more global, it’s easy for the link between a particular position and the greater whole to become obscured.

Although we often hear employees recite broad corporate mission statements, the way people interpret and internalize those statements up and down the management chain can make all the difference in how engaged and effective the organization is. Far too often, different people interpret the same words in vastly different and conflicting ways, and many cannot connect what they do each day to what the broader organization is trying to achieve. Performance at the individual, business unit, and companywide levels can suffer as a result.

The connection between position and outcomes undergoes extra stress during times of major organizational change, such as a shift to agile ways of working . In our experience, however, this usually happens because the company is focusing on the mechanics of agile, such as squads and tribes and two-week sprints, and deemphasizing critical principles, such as customer collaboration, customer satisfaction, and the idea that work done with clarity produces better outcomes. Unless leaders are committed to achieving strategic clarity and supporting the work that goes into it, no major change—agile or otherwise—can succeed.

Define the Outcome

How do some organizations create consistent alignment while so many others assume that alignment exists when it doesn’t? The head of retail banking for a large North American financial institution was running multiple agile pilots while he tried to figure out what the new way of working was all about. He dropped in on an agile sprint review one day (something we advise senior leaders to do regularly) to check on progress. The team’s charter was to shift customer requests for debit card support from the call center to the website and the mobile app—an important business outcome because customers’ digital experiences are generally better than their call center interactions, and digital support is less costly for the bank to provide.

The team had been empowered to work out which specific software features, operational changes, and promotional programs would drive a 10% reduction in call center traffic over the following six months while increasing customer satisfaction. The retail banking CEO asked team members to talk about what they were doing and why they were doing it. To his astonishment, every member could tell a brief story connecting their work directly to the team's target outcomes—and to the bank's overall purpose of pleasing its customers.

He said afterward, “Now I understand why we’re adopting agile. The clarity of focus and purpose in that team is what it’s all about. They're creating value, not just delivering features. And they care about what they’re trying to achieve.”

Effective leaders do not leave to chance the most important ways to create value. They understand that their most important job is to define the business outcome clearly and give teams the autonomy they need (within appropriate guardrails) to achieve that outcome. Over time, they clearly and consistently articulate the purpose and objectives of the task at hand, but they do not dictate how to perform it. Because agile depends on engendering alignment through autonomy, it provides a powerful discipline for articulating purpose. Often companies fail—regardless of whether they adopt agile—when people are given ambiguous goals or misinterpret what they are supposed to achieve and are not corrected. This leads to wasted resources at best and worthless outcomes at worst.

Effective leaders understand that their most important job is to define the business outcome clearly and give teams the autonomy they need.

Getting to Why

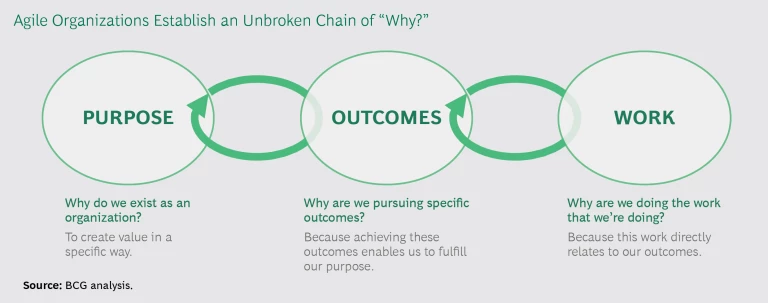

We have written before about the importance of defining objectives and desired outcomes—the why of what a company does—as well as of focusing on principles over practices, putting the right leadership in place, and establishing alignment to enable autonomy . For agile to be successful, all of these pieces must be in place. Agile organizations are especially good at establishing “an unbroken chain of why,” which is simple in conception but far from easy to implement. (See the exhibit.) This unbroken chain establishes links between the business outcomes that the company needs to achieve and the work that individual teams are charged with delivering. A well-run agile process reinforces the chain of why and defines clear outcome metrics. Even if a company isn’t applying agile, the unbroken chain of why can still have tremendous value.

The chain of why enables agile organizations to establish proper alignment by in various ways:

- Articulating clear purpose, strategy, and outcomes for the group’s output, and linking that output to broader company goals

- Pressure-testing the outcomes’ boundaries in terms of scope and interdependence, to ensure that everyone understands the objectives in specific terms that they can act on

- Inventorying and organizing the blocks of work needed to accomplish the specified business outcomes

- Dividing the blocks of work and assigning the components to teams that, in turn, will coordinate with one another and use metrics such as objectives and key results (OKRs) to show progress toward the outcomes

- Correcting course in response to new data or direction

One of the most powerful benefits of agile is the ability to quickly recognize when things are going off course and to adjust on the basis of learning. If teams have the right capabilities and knowledge, and if they have internalized their business outcomes, they can make better decisions about what to pursue and when to stop doing things that no longer make sense. How companies can more broadly enable agile is the subject of a forthcoming companion article on how agile delivers.

One of the most powerful benefits of agile is the ability to quickly recognize when things are going off course and to adjust on the basis of learning.

Companies that get agile right see impressive results: three to four times higher customer satisfaction and return on digital investment, for example, and reductions of 15% to 25% in development costs. Surveys show levels of employee engagement at 90% or greater.

Some executives fear that iterative ways of working will mean loss of control and, inevitably, chaos—but the chain of why serves as the check against this. When teams understand their purpose in customer and business terms, and when they act within well-defined guardrails, the alignment provided by architecture and other standards allows teams to innovate within defined parameters. Though it may seem counterintuitive, alignment on the basis of why actually enables autonomy, which is why agile works.