Companies have always needed to be clear about who they are and what they want to be. A strong corporate vision can open up new business opportunities and energize the organization. Yet today, fixing that vision too rigidly can limit its shelf life, particularly in a world where technological, geopolitical, consumer, and other disruptions are the norm. A willingness to challenge the status quo and rethink strategy should be part of the corporate DNA. This often means moving in unexpected directions—by zig-zagging.

To make new things again and again, you need sometimes to change the way you look at those things.

To make new things again and again (zigging), you need sometimes to change the way you look at those things (zagging). The zig-zag involves mental shifts, quests for unfulfilled opportunities, business model innovation, expanded ambitions, and thinking the unthinkable.

Take Amazon. It became an expert bookseller but then zigged to capture more of the consumer wallet by selling everything —and then zagged by harnessing its expertise in the cloud to offer web services. Essentially, Amazon’s zag involved changing how it thought of itself, as not just a seller of goods, but as an organization with expertise in web services.

In its early days, Michelin made an interesting zig-zag. In 1900, André Michelin, who with his brother Édouard founded the tire company, wanted to find a way to encourage car owners to drive more. At the time, vehicle unreliability and the likelihood of encountering problems—often, flat tires—deterred people from taking long or frequent journeys.

The solution? Offer drivers a free list of garages. The Michelin Guide of garages was gradually improved with additions such as mechanics’ names, pictures of the garages, maps, lists for other countries, and, starting in 1922, a price tag to purchase the now-invaluable guide.

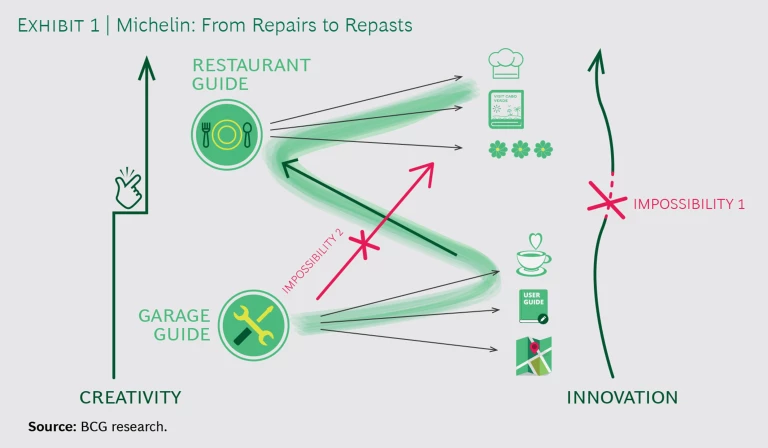

As the bottom of Exhibit 1 shows, building on a successful existing idea—in this case, a directory of garages—enables continuous improvement, or zigging, and the inflow of innovations that can be applied to that basic concept. And while zagging usually means facing headwinds, once you have zagged, you can enjoy the tailwinds when zigging.

Pursuing the Zag

Such an approach to innovation is iterative, profitable, and enables the maximum to be extracted from an idea that has been turned into a successful product or business model. But in a constantly changing world, relying on the same idea can be taken only so far. Milking it produces ever-lower returns. Eventually, you need a paradigm shift that can enable a completely different approach—the zag.

Here’s how it happened at Michelin. While exploring ways to improve the garage directory, the company realized drivers got hungry while waiting for their cars to be fixed. Why not recommend a restaurant near each garage?

Rather than seeing this only as an incremental improvement, Michelin also made a mental shift, transforming a directory of garages with information about restaurants into a directory of restaurants. That represented a breakthrough. And the restaurant directory led to further improvements—and so the idea to rank restaurants with “Michelin Stars” was born.

Genuinely fresh thinking demands such disruptive change in perception, a shift in the mental model. Only this leap of creativity can produce a “ new box ” (on the top left of Exhibit 1), which unlocks the innovation process once again (on the right) to enable a new wave of growth.

In retrospect, the Michelin restaurant guide was a great idea. But the only way the company was able to get to it was to zig-zag. Zigs are incremental and exploratory—you need them, but they aren’t enough for the kind of paradigm shift that comes from zagging.

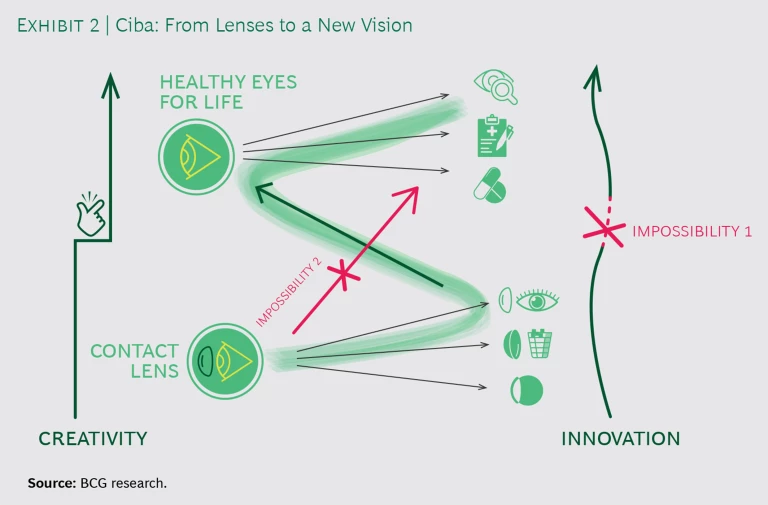

Ciba Vision also zagged in the 1980s. The company, which sold contact lenses and related eye-care products, faced stiff competition from Johnson & Johnson, particularly after J&J launched a disposable contact lens in 1987. While Ciba Vision had produced some innovative products like bifocals, the company’s president, Glenn Bradley, knew that J&J’s economies of scale posed a serious risk to the company’s long-term profitability. Zigging—making incremental adjustments—would be insufficient. (See Exhibit 2.)

Over the next five years, in a concerted effort to find the “zag,” Ciba Vision launched a series of innovative contact lens products and pioneered a lens-manufacturing process that dramatically reduced production costs, enabling it to overtake J&J in some market segments and generating profits that enabled ongoing experimentation.

Critically, however, the company also launched a drug for treating age-related macular degeneration. While this might seem an unlikely strategy for a contact lens maker, Bradley and his team had identified a new North Star—“Healthy Eyes for Life”—that linked the company’s breakthrough initiatives to its conventional operations, uniting employees around a common cause and preventing organizational fragmentation.

Ten years later, sales (which had been stuck at about $300 million a year) had more than tripled, to more than $1 billion, and the new drug, transferred to Novartis’s pharmaceutical unit, was on its way to becoming a billion-dollar business. What enabled such a breakthrough at Ciba Vision was not just an incremental process of innovation but a new way to frame the problem, opening the door to a different way of thinking about the business.

Challenging long-held assumptions in this way may not change the bottom line overnight. But it can enable a company to head in new directions, or even to evolve into a new kind of enterprise.

Consider Monsanto. In 1982, a team of scientists working at the company modified the genetics of a plant cell, laying the foundation for genetically modified crops. Today, those crops account for most of the soybeans, corn, and cotton grown in the United States and have transformed the global seed industry. This invention did not come from a start-up or an academic lab but from a team of scientists working for an 81-year-old company.

Since then, Monsanto has zagged from being an agricultural chemicals company (with constant zigs in that area) to divesting most of its chemicals business to focus on biotechnology and GMO seed sales (with constant zigs in that area as well), which ultimately led to its acquisition by Bayer in 2018.

Today, digital transformation offers rich opportunities for zags. Take China’s BYD Company, founded as a battery manufacturer in 1995. After capturing half of the world’s cellphone battery market, it moved into other forms of rechargeable batteries (a zig), including for electric cars. By moving up the value chain, the company has built capabilities that it has harnessed to compete effectively and then dominate new sectors, such as electric car manufacturing.

Digital transformation offers rich opportunities for zags.

Laying the Foundations

Of course, while the kinds of creative shifts we just described may seem obvious after the fact, the change in mindset that enables them does not always come easily. Such shifts require a corporate environment where continuous evolution and rigorous experimentation are the norm, where challenging the status quo is celebrated, and where risk, thoughtfully considered, is embraced. Such a culture enables swift reaction to potential disruptions (from the entry of a competitor out of left field to regulatory and societal shifts) and business opportunities (changing consumer behaviors or gaps in the market).

Without such a culture in place, disruptions and opportunities may be missed or not addressed fast enough. For example, it took almost a decade before someone noticed that farmers were removing the back row of seats from their new Model T Fords to use the vehicle to haul things. If dealers had thought about this differently, the pickup truck might have been invented sooner than it was. And had more people noticed the potential disruption heralded by the iPhone, producers of everything from cameras to listening devices might have been able to weather the storm that followed its invention more effectively.

To get started on the path to zig-zag, encourage your people to take thoughtful risks and challenge assumptions.

So how should a company get started on the path to zig-zag? First, set the conditions by establishing norms that make nonlinear thinking possible—in particular, encourage your people to take thoughtful risks and challenge assumptions. Once the culture is in place, find ways to monitor changes in the external environment—from shifting customer expectations to new technologies and emerging trends. Being alert to the threats and opportunities that trends present allows a company to react more swiftly.

Finally, companies can use specific tools to operationalize zig-zagging. These include:

- Taking the perspective of a different company or stakeholder. How might another organization or individual approach the challenge or opportunity you want to address?

- Exploring how to apply different forms of business model innovation to your company, such as shifting from selling products to selling services, or moving to a low-cost model, or developing a peer-to-peer model—to name but three archetypes.

- Looking at where leading VC players are investing, or tracking new-patent filings.

- Finding new ways of learning, such as taking executives into a completely different business environment. For example, some US grocery chains send their managers to visit leading-edge retail networks in Europe, while mining companies have been sending leaders to meet Indian consumers and suppliers.

Zig-zagging means experimenting constantly, scanning the horizon for new perspectives, and maintaining a portfolio of possibilities that could enable the enterprise to evolve into something fresh and new. There are many ways to get there, but today, as businesses from taxi services to hotel chains are being challenged by the likes of Uber and Airbnb, with similar disruptions across every other industry, the ability to zig and zag at the right moments has never been more important. Not only can zig-zagging help companies avoid downside risk, but it also can open doors, align teams behind a new vision, and reshape a business to meet the demands of a world where the only constant is change itself.