To create a more balanced and equitable workforce, the industry needs to understand how crucial moments of truth draw women to tech careers—or push them away.

Southeast Asian technology companies have a strong track record of hiring women—better, in fact, than tech companies in many developed countries. Yet the region has further to go in order to reach true parity in the number of women who work in tech compared with other industries. Boosting gender diversity in technology industries provides clear value. BCG research has found that companies with more women in their workforces and leadership teams show better performance. And a more vibrant technology sector can help national economies grow.

BCG recently partnered with Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), a government agency tasked with developing and regulating the technology and media industries in that country, as well as SG Women in Technology, to study gender diversity in technology across a variety of Southeast Asian nations, increase awareness of the underlying issues, and identify solutions.

Our proprietary research, including both quantitative and qualitative findings, revealed three moments of truth that play a key role in women pursuing long-term careers in technology : their choice of major at college, selection of first job, and decision to stick with a technology career once they have started. At each of these moments of truth, specific interventions can lead to increased gender diversity in the tech sector—both proven baseline measures and hidden gems (those that are not widely available in the region but are perceived to be effective). Yet isolated initiatives won’t suffice. Instead, the challenge calls for a holistic, end-to-end approach that spans all three moments of truth.

Progress on gender diversity in tech won’t come without collaboration—this needs to be a coordinated, multistakeholder effort.

Moreover, progress won’t come without collaboration. This needs to be a coordinated, multistakeholder effort. To that end, we defined three concrete recommendations for each of the key stakeholder groups—companies, governments and schools, and women themselves.

The gender gap at technology companies in Southeast Asia is an exacerbated symptom of the broader problems that women face in all industries. Yet the industry’s rapid growth, need for talent, and attractive career characteristics position it to lead in solving those problems. Tech can be a powerful lighthouse for change. People are increasingly conscious of the gender imbalance in the technology industry. This publication sheds further light on the issue and helps organizations move from awareness to action.

The Intersection of Several Emerging Trends

It’s hard to imagine a more relevant topic in the business world right now. Southeast Asian economies are among the most dynamic around the globe. Technology is radically disrupting businesses and industries. And digital talent is now the core of most companies’ people initiatives (including software development, data science, data visualization, and cloud expertise).

The demand for digital talent is growing faster than the supply, leading to many vacant positions. In cybersecurity, for example, the worldwide workforce faced a shortage of approximately 4 million people in 2019, including 2.1 million across the Asia-Pacific region. And the problem has been getting worse. In Singapore, 5% of technology jobs were vacant in the first quarter of 2020, nearly double the vacancy rate of 2010 (2.7%). Among IT and other service-related positions in Singapore, the first-quarter 2020 vacancy rate was even higher, 6.1%.

At the same time, gender diversity is a growing area of focus for many organizations as they recognize the benefits of creating more balanced workforces and leadership teams. BCG research has shown that gender diversity can make companies more innovative and agile and improve their financial performance. For example, companies where women account for more than 20% of the management team have approximately 10% higher innovation revenues than companies with male-dominated leadership. Beyond the direct financial impact, diversity is also increasingly important for organizations’ culture and ability to attract better talent; in addition, it has been found to improve companies’ customer service and brand perception in the market.

Gender diversity can make companies more innovative and agile and improve their financial performance.

The recent COVID-19 crisis is also spurring change. The pandemic is redefining the traditional workplace, with working from home becoming the norm in most countries across the region. This new setup could lower some of the barriers to women’s participation in the workforce, such as needing to constantly balance time away from home—commuting or at work—with family obligations or having to work in less female-friendly physical environments. The pandemic also has the potential to exacerbate the situation, however, because many women shoulder a disproportionate share of the childcare burden and that burden has risen substantially during the crisis. But if the new reality is leveraged wisely, it may allow workers to be judged more on the merit of their outputs versus facetime in the office and, in turn, support the growing female workforce.

Given the critical shortage of technology talent—and the clear gains from more balanced workforces and leadership teams—women need to be part of the solution. Yet little objective research has been done about the actual state of women in technology across Southeast Asia. To fill that gap, we surveyed around 1,650 women in six Southeast Asian countries.

The analysis generated several key findings.

A Comparatively Good Starting Point

We found one encouraging sign: the region is starting from a relatively strong baseline of gender diversity. In fact, the participation of women in technology across Southeast Asia is slightly higher than global averages, in terms of both the number of college graduates with technology degrees and the overall tech workforce. (See Exhibit 1.) Notably, the region leads several mature Western markets in female inclusion, including the US and UK.

Women in the region also have a positive perception of the industry’s efforts, with approximately 65% agreeing that the tech sector does better than other industries in offering programs specifically tailored to recruit, retain, and promote women.

But More Work Ahead

Women often leave their job at key junctures of the career ladder in all Southeast Asian markets—the topic of a previous

BCG publication about diversity in Southeast Asia

.

The challenge is particularly acute for the technology industry, where women’s participation in school and the workforce is systematically lower than in other industries. Of technology majors in Southeast Asia, for example, 39% are women (compared with 56% for all other fields of study). And in the workforce, women account for 32% of the region’s technology sector, compared with 38% of the total workforce.

There are some inter-regional differences worth noting:

- Singapore and Vietnam have the lowest share of women with technology majors in the region yet both have higher shares of women working in technology, with Singapore among the highest of the six countries we studied, at 41%. That is likely driven by the booming tech sector in both countries, which attracts women from nontechnology education backgrounds.

- The Philippines and Thailand have the highest share of women technology graduates across Southeast Asia (48%); Thailand also has the highest percentage of women in the technology workforce (42%).

- Indonesia has the lowest share of women at technology companies (22%), in line with the lowest percentage of women in the overall workforce (32%).

These regional differences show that a single homogeneous approach will not work. Instead, companies and governments need to understand the factors that influence women at every step of the career funnel, in every market.

Highly Valued Gender Diversity Programs

Some companies and universities have launched programs to increase women’s participation, and female employees find those initiatives beneficial. Approximately 80-90% of women said that they have personally benefited from these programs where they are available. More than a third of all respondents reported that their companies have no such initiative in place—a clear opportunity for companies to improve. Exhibit 3 shows a breakdown of the perceived availability of gender diversity programs in our respondents’ companies by tech segment. Although the majority of tech segments perform at relatively similar levels, IT and data services are ahead of the pack, at 74%, while tech hardware and equipment manufacturers as well as semiconductor companies are slightly more challenged, at 53% and 43%, respectively.

Three Moments of Truth

To improve, companies and policymakers need to take a targeted approach that focuses on the critical junctures in a career—those moments of truth that can have a disproportionate impact in shaping a person’s future in tech. Our research identified three such moments, along with the key influences that have the biggest effect on women at each juncture, either driving them toward or deterring them from a career in tech. (See Exhibit 4.) We also developed a menu of initiatives that can boost progress for women at each of the three moments of truth.

The Choice to Pursue Higher Education in Technology

The first moment of truth is when a woman decides what to study at college. Quite simply, without the right educational resources—accessible to all—countries will have a hard time building a skilled workforce and companies will struggle to find talent. Schools in Southeast Asia have made significant progress in this area recently. In the past, physical access to educational facilities and peer influence were significant drivers in shaping a person’s decision to study technology; today, both factors have diminished in importance. Instead, the choice of education (for or against technology) is shaped primarily by personal interest.

Without the right educational resources, countries will have a hard time building a skilled workforce and companies will struggle to find talent.

Across the region, societies place substantial emphasis on education as a means of social mobility and a stepping stone toward greater career opportunities. Given this geographical context, there is an even bigger need to recognize the importance of education—and the choice of major—as a gateway for women to gain an initial footing in the tech world.

Soh Siew Choo, the managing director and group head of consumer banking and big data/AI technology at DBS Bank, told us, “I chose to pursue a computer science degree because I had a keen interest in mathematics and logic, and I’ve always been interested in using logic to automate things. I chose to follow my interest despite my cohort having fewer than 10% women at the time. This is thanks to my parents, who were supportive of me pursuing my passion even though computer science was only considered a promising innovative discipline rather than one that was already established and prestigious.”

Another leader we interviewed, Richa Menke, who is the director of strategic design at BCG Digital Ventures, said, “My mother had studied physics and my dad was a professor of electrical engineering. Needless to say, I grew up in a family that didn’t just think that studying math was important but one that had a strong love of the subject. I may not have shared their love for it at the time, but I knew I could learn it. By nature, I was more attracted to creative, expressive pursuits, but having that early exposure helped me later enjoy math and ultimately study engineering. I think it’s important to expose children early so they can assess their interest free of conventional expectations.”

For a majority of high school girls, a critical hurdle to deciding to study technology in college is an overall lack of familiarity with the field, suggesting that high school counseling—generally available in most regions—could be effective in boosting the ranks of women with technology degrees. The lack of exposure for girls to technology topics in secondary school is a challenge worldwide. Furthermore, the perceived difficulty and narrowness of tech studies are highlighted as critical deterrents for women who choose another educational path.

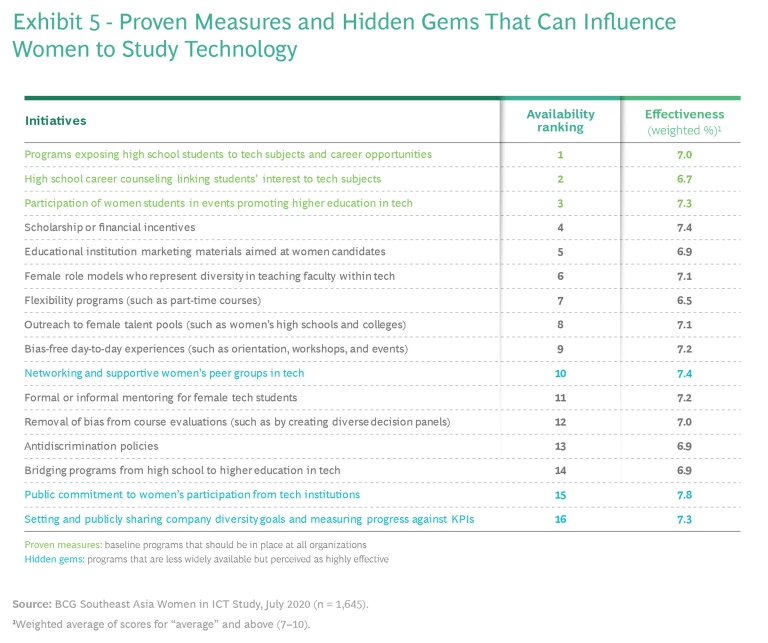

Looking at concrete initiatives to influence more women in Southeast Asia to study technology at college, we identified both proven, well-known baseline measures that all companies should have in place and hidden gems, initiatives that are perceived as the most effective by respondents in our survey but less available in the region. (See Exhibit 5.)

Our survey found that the most significant proven measure is creating programs that expose school-aged girls to technology subjects and career opportunities. For example, the Ministry of Education (MOE) and IMDA in Singapore jointly launched a program called Code for Fun that introduces all students in upper primary school to computational thinking through coding. This program helps participants develop an appreciation of core computational thinking and coding concepts using simple visual programming-based lessons codeveloped by MOE and IMDA. It also exposes them to emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence.

Even programs that are not targeted specifically at girls can be strong platforms—when promoted in an inclusive manner—giving equal chances to girls and boys to gain some familiarity with technology topics early in life.

In addition, our research found some hidden gems for boosting the number of women who study tech in college. For example, when institutions make a public commitment to women in technology, it makes a difference. Notably, about one-third of technology programs at universities in Southeast Asia do not have any initiatives aimed at boosting gender diversity—a significant shortfall. At those that do, more than 80% of female students indicated they have personally benefited from such programs, highlighting the importance of these initiatives. Women’s networks and measurable goals were also cited as hidden gems in increasing the number of women studying technology.

The Selection of First Job

After education, the second moment of truth is women’s choice of first job—whether they opt to work in technology or some other field. According to respondents, the most influential factor shaping decisions about a first job is the opportunity to follow their educational path, which highlights the importance of increasing the base of the funnel and attracting more girls to pursue technology education. Secondary factors are a personal interest in the topic and competitive pay and benefits.

Among women who studied technology in university and chose not to enter that field in their first job, most cited a lack of interest, the perceived difficulty of working in that field, and narrow career prospects—which are also the main reasons that women refrain from studying technology. In other words, they believe that starting a career in technology would mean they would always need to work in technology.

Digital-native companies—those that have launched specifically to capitalize on the digital economy and operate entirely online, such as Grab, Lazada, and Facebook—seem to have overcome this apprehension. Respondents indicated that they perceive digital natives to be highly attractive for first jobs, exactly because these companies offer more versatility, strong learning and development opportunities, and good opportunities for career advancement as well as high pay.

As Exhibit 6 shows, proven measures to ensure that graduates—from technology and other majors—move into jobs in the field include university career counseling that provides students with an accurate sense of the opportunities and an understanding of what the day-to-day job experience could be like. Company-led initiatives that expose women to what tech careers could entail was another frequently cited proven measure. DBS, a leading financial services group in Asia, has launched several programs to more effectively recruit women into its technology functions. One, called Hack2Hire-Her, involves coordinating with tech women’s networks to increase the bank’s outreach and raise its profile.

A hidden gem in this area continues to be a public commitment to gender diversity by company leaders, along with structured bridging programs that can link university students to companies before those students are looking for a job.

“I was fortunate enough to complete two IBM internships while I was in university,” said Stephanie Hung, senior VP at ST Engineering, a global technology, defense, and engineering group. “I felt it was a logical move to join IBM upon graduation, even though I had other job offers, as I felt comfortable with IBM’s culture and appreciated the IBM graduate-training program for fresh graduates. I believe getting early exposure to companies through industry attachments helps improve the quality of recruitment and tenure of employees.”

The Decision to Remain in a Technology Career over the Long Term

In virtually all industries and geographic markets studied in our survey, respondents envision more varied career paths nowadays and—unlike the previous generation—don’t expect to stay at a single company for their entire career. But counter to what some might expect, women at technology companies reported slightly higher loyalty to their employer and anticipated staying longer than in other industries. According to these women, the primary factors leading to a lengthier tenure include compensation and attractive career opportunities, along with a reasonable work-life balance. In fact, work-life balance is a key differentiator in both positive and negative terms. Most women who have this at their current company value it highly and plan to stay; those that don’t have it—particularly women with children—plan to leave their organization. (In some markets, COVID-19 has exacerbated the burden on working parents .)

Learning and development opportunities also carry significant weight in boosting female retention. Our findings highlight that these are important criteria in women’s decision to join the technology sector, and the absence of such training was cited as a key reason that some women plan to leave their job. Notably, learning and development are becoming more important for younger generations—something that leadership teams need to know as they build their workforce of the future.

As Exhibit 7 shows, proven measures to build long-term careers include participation in diversity-related external events and rankings, employee surveys, a public commitment by the CEO, and making diversity goals and progress public in order to increase transparency. Having a diverse leadership team was another highly rated proven measure.

Hidden gems include offering appropriate health care coverage and structural workplace interventions (such as nursing rooms). Respondents ranked both as highly effective, but these benefits are not widely available in the technology sector across the region.

Finally, female role models are crucial—in sponsoring more junior women, networking, and championing diversity. This is something that earlier BCG research into gender diversity has repeatedly shown to be true across all industries and geographic markets.

In addition to these broad insights for the entire region, the analysis pointed to several nuances among individual countries. (See “Country-Specific Findings.”)

Country-Specific Findings

Indonesia. Peer influence plays a disproportionate role in the choice of education for respondents from Indonesia, while company reputation plays a much more important role in the choice of first job and long-term career than it does in other markets.

Malaysia. Respondents in Malaysia place a high importance on role models and mentoring in school and at work. Yet work-life balance is more of a consideration earlier, at the start of their career, and financial issues come into play across life stages.

Philippines. Family influence and exposure to tech topics early in women’s lives play a bigger role in their choice of education and first job, while pay becomes more important for long-term career retention.

Singapore. Respondents from Singapore highly value women’s networks, which can offer role models throughout their education and career. At the start of their career, higher pay and job responsibilities appear to be particularly important while, in the long term, the emphasis is more on work-life balance and flexibility.

Thailand. Family and societal influence have a larger impact on women’s choice of education, while pay, recognition of their contribution, and job responsibilities become more important in their professional lives.

Vietnam. Societal influence plays a bigger role in the choice of education, while learning and development are disproportionately important for women’s first job and company culture, while work-life balance matters more for their long-term career.

Recommendations for Stakeholders

Our research points to specific actions that all stakeholders in Southeast Asia—technology companies, governments and schools, and women—can take to make faster progress in gender diversity, in a coordinated way.

Technology Companies

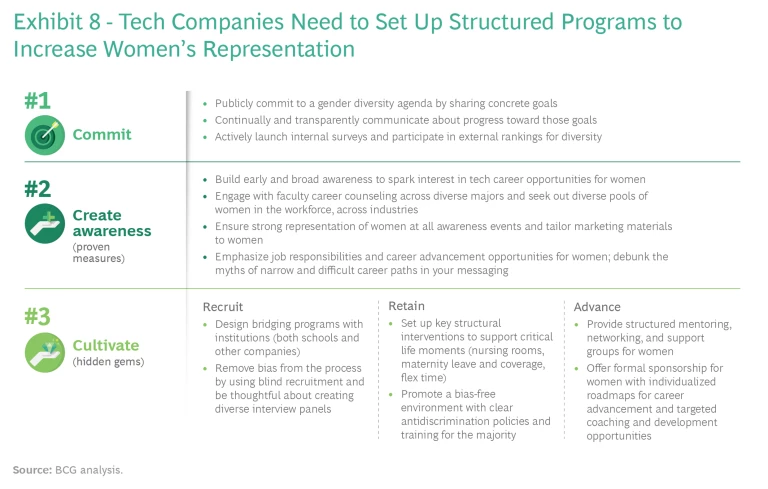

Technology companies should focus on three main priorities.

Set up structured programs that include both proven measures and hidden gems. The first priority for all technology companies is to develop, or reinforce, their own gender diversity programs spanning women’s entire careers, as described in Exhibit 8. These initiatives need to commit, create awareness, and cultivate. Start with a clear commitment and public goals. Then, ensure that you have all proven measures in place—the must-have efforts to build knowledge and create awareness on the tech topic across the funnel. Then go much further to cultivate the careers of women in your organization by systematically implementing hidden-gem initiatives. These highly effective programs are less available today yet critical to accelerating progress.

Build the pipeline creatively. In the short term, along with setting up structured programs, companies should work to expand their talent pool by looking beyond pure technology profiles, as some technical roles and skills can be built on top of other critical capabilities. Women with different backgrounds (such as in sales) can contribute a lot to your company and grow into successful technology leaders.

Companies should work to expand their talent pool by looking beyond pure technology profiles.

“Women tend to think they need a tech background to join the t tech industry . Even if you didn't study STEM, you can join the tech industry and progress in your career. In my view, we can always learn about tech itself on the job. It’s a lifelong learning, and we need to keep adapting to new technology that will come,” said Nok Anulomsombut, CEO of Sea (Thailand), parent company of Garena, Shopee, and SeaMoney.

Aliza Knox, head of APAC for Cloudflare, agreed: “Women think that to join the space, you have to have a technical degree, but I didn’t have a technical degree and first got into the industry because I had sales experience in the region, which is what they were looking for then. There are other pathways, other capabilities that you can offer to be part of the industry. You can learn the technical skills later.”

In the long term, wherever possible, companies need to start outreach to women as early as high school in order to encourage interest in tech, because it’s a key driver of choice for education and first job.

Start at the top. Having a critical mass of women in senior roles often correlates with a higher rate of women across the company. Women at the top naturally change the culture, as inclusiveness becomes effortless. Go the extra mile to hire, transfer in, or promote the right female talent for these key positions. This will also ensure that role models and informal mentorships develop, which are both key enablers for other women to envision a long-term career in tech.

“When you look at improving gender diversity in your company, you need to start from the top,” said Anika Grant, global director of HR at Dyson. “Senior women leaders help change the culture, the tone, the type of decision making, and the way communication is done. That creates a cycle that helps attract women across different levels of the company going forward.”

Governments and Schools

Governments and schools should focus on these three priorities.

Shape a conducive education curriculum. Governments and schools play a critical role in helping girls in high school and college and women in the workforce get an equal chance at developing interest, knowledge, and skills in technology. To that end, government authorities and educational institutions should ensure that a technology curriculum starts as early as possible and that the environment is attractive and conducive for female students (for example, by ensuring that women are part of the faculty). Women already in the workforce should also have access to additional training in both the hard and the soft skills required to further their careers.

“Women need better support systems and better training and development opportunities on how to be confident and how to sell themselves. We also need to learn all of this as early as possible—in school even,” said Clare Markham, cofounder of StartupToken, a leading accelerator for innovative blockchain projects.

Provide the right supporting guidelines. Governments can set further standards to support women’s careers in technology. For example, they can establish regulations requiring structural workplace benefits, such as nursing rooms, maternity (and paternity) leave, and childcare support. Externally, governments can also foster community awareness and provide assistance—for example, by promoting awareness campaigns about gender diversity and enabling an effective childcare support system in the country.

Foster industry collaboration. Partnering with industry can help build strong women’s networks and ensure that best practices are leveraged across all technology sectors. For example, initiatives such as MentorConnect—a cross-company mentorship program dedicated to diversity in the workplace, led by Dell Technologies and supported by a mix of public and private players (including IMDA, Salesforce, and ST Engineering)—could make more women mentors available to more junior women seeking career guidance. Governments across Southeast Asia can play a role in orchestrating this kind of collaboration and providing a clear commitment and objective goals at a national level.

Women in Technology

Finally, women in the technology industry also have a personal responsibility to help drive this change, hand in hand with the broader structural actions discussed above. Here are three key priorities for women in tech.

Develop both hard and soft skills. Women need to define what success means for them and be proactive in building the right skill set to support their own career development goals. Critical capabilities include both technical knowledge as well as softer skills such as communication and leadership to provide women with the self-confidence they need to be successful leaders. Women have a responsibility in shaping their careers and shouldn’t wait for companies to offer these programs; they can help build them or source them externally. In that regard, women should continue to network outside of their role and company, in order to find these opportunities.

“You have to continuously invest in your personal development and be aware of your strengths and weaknesses,” said Issa Guevarra-Cabreira, managing partner at 917 Ventures, a corporate incubator in the Philippines. “You also need to be open to acknowledge what you know and don't know and ask for help from other leaders. People are always willing to help and be part of your journey and growth, men included, if you ask for it.”

Dr. Pan Yaozhang, the head of data science at Shopee, said, “As a female leader in the tech industry, I truly believe that women are crucial to the future growth of the industry. As we continue to see technology become an integral part of today’s digital economy, I strongly advise women who are interested in pursuing careers in tech and data science to hone relevant skills, familiarize yourselves with the latest technologies, connect with, and learn from, female mentors in STEM industries.”

Find the right balance for yourself and support others. Role models are consistently cited as one of the most critical drivers for diversity, in virtually all industries and geographic markets. There are as many different profiles for role models as the number of women in the workforce. What they all have in common, however, is the ability to find their own balance for a fulfilling career.

Role models are consistently cited as one of the most critical drivers for diversity.

To achieve this goal, a number of women leaders we spoke to have had to overcome their initial hesitancy about putting their hands up when an attractive opportunity becomes available. Despite having the required skills and ambition, women in the region still tend to be less likely to speak up for what they want. Women have a key role to play in advocating for themselves in order to then advocate for others. Championing women where possible and becoming an active mentor will make a real difference to women’s participation in the industry.

“I was the only female consultant in the office during the initial days of my career (very different from the very diverse team we have today!). Going through this journey made me realize how important mentorships are—the ability to have conversations with female role models is absolutely key and can create such a multiplier effect,” said Vaishali Rastogi, a managing director at BCG and the global leader of the firm’s work in technology, media, and telecommunications.

“We need to champion women by encouraging them to take up responsibilities that help them progress forward and advocate them for promotions when the moment arises,” said Pauline Wray, the head of Asia for Expand Research and global lead for BCG’s FinTech Control Tower . “If there is an opportunity to promote a woman that is doing well or let a female analyst take the lead in a senior client presentation, I do so.”

Bring your male colleagues along. Gender diversity is not a women’s issue; there is persuasive evidence that the most successful gender diversity programs are those that involve men’s participation . Women have a key role to play in taking their male colleagues, partners, and friends with them on the journey, making them aware of challenges and brainstorming solutions to turn men into ambassadors for diversity both at home and at work. Encouragingly, millennial men are far more aware of the uneven playing field that women face at work and far more likely to take steps to rectify the problem.

Gender diversity is that rare issue in which the solution benefits everyone. For technology companies in Southeast Asia, recruiting, hiring, and promoting more women will unlock value and improve performance. For countries, diverse workforces and leadership teams will lead to more vibrant economies and faster growth. And for women, true gender equity in the workplace will give them the fair shot they deserve.