The only certainty about the COVID-19 pandemic is that it will eventually end, and when it does, many of the changes it has brought will recede. Like wildlife returning to Chernobyl, prior conditions will reappear. Consumers will once more shop and socialize, supply and demand will rebalance, and markets will recover. History tells us, however, to also expect some lasting change in the wake of crisis—such as Glass-Steagall after the Great Depression, increased suburbanization after World War II, and heightened security following 9/11. Similarly, in the wake of turmoil, company performance and position can either shift temporarily, or permanently. This outcome depends on the interplay of customers, competitors, and regulators. It also depends, importantly, on the decisive actions companies and their leaders take in the middle of the crisis.

Companies that master both the transitory and the transformational response to a crisis reap long-term rewards. Transitory responses entail rapid actions that are critical for survival , including protecting employees, managing cash, and flexing supply chains to meet demand. But occupying new positions and building new advantages requires transformational moves and investment. In a crisis, when the immediate response can be all-consuming, transformational moves are harder. They are also smarter, and create opportunities to win in the long term.

Two leading US watch manufacturers, Bulova and Waltham, traversed the serial crises of the 1920s to 1940s. Both launched immediate responses, for example, by extending terms to retailers in the Great Depression and by later successfully shifting production to wartime instrumentation. Beyond this, Waltham largely pursued a course of tight cost management, curtailing advertising, innovation, and investment in sales and distribution.

In contrast, Bulova consistently invested in new sources of advantage, acquired multiple domestic and international competitors, and innovated as it spent. During this time, the company launched the industry’s first-ever million-dollar advertising campaign, the world’s first television commercial, and was an early innovator in electric clocks and clock radios. Bulova’s leaders also cultivated close government relationships, selling products to the government at cost, and opening a watchmaking school that employed disabled veterans—all while aggressively lobbying to impose tariffs on imported watches. Bulova became one of the era’s ten best-performing stocks, and from 1931 to 1954, its value appreciated by a factor of 24.

Waltham went bankrupt.

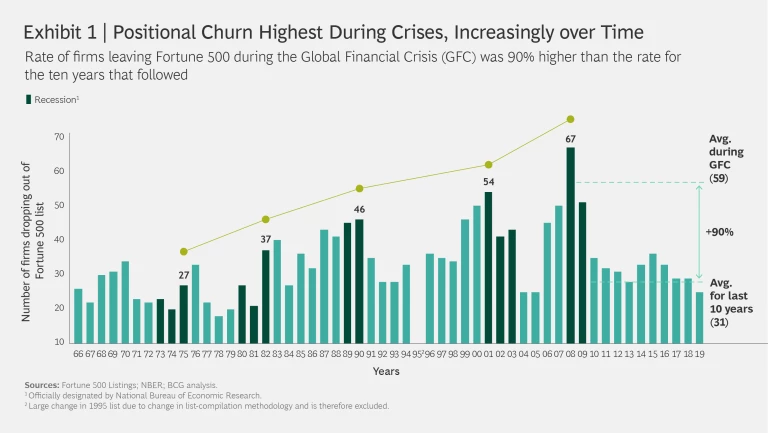

Exhibit 1 shows the prevalence of this storyline. Volatility in company position is greatest in times of crisis and has steadily increased with successive crises over the last 50 years. Fortune 500 churn during the last recession was 90% higher than the average of years since.

Bulova’s example suggests that winning beyond a crisis requires finding transformational opportunity signals in the midst of transitory noise.

The Five-Point Approach to Transformational Responses

Our experience with companies that have mastered the ability to identify transformational opportunities suggests five points of action:

1. Detect and discern critical shifts. Stay ahead of the curve by setting up three war rooms: one for customers, one for competitors, and one to consider regulatory issues. Building these cross-disciplinary teams will help companies determine which signals related to demand and competition are most relevant to monitor, which are likely to persist after the crisis, and which reveal opportunity. In a crisis, the detection cycle is fast, and can even occur on a daily basis. In a prior crisis, one cruise company war room monitored credit card spend, detecting timing and patterns of early returning travelers. Currently, a client is looking at road congestion levels in China to discern the shape of the post-crisis rebound.

Such insights must be integrated into all three war rooms to discern patterns of longer-term opportunity. Following 9/11, for example, Qantas was able to guide its expansion plans and gain market share by monitoring customer data in addition to its competitor capacity and routes. CGI, a technology consulting firm, gathered detailed survey results through one-on-one field interviews with a quarter of its customers conducted by local senior executives. The results yielded competitive insights that led to a series of adjacent acquisitions through the downturn from 2007 to 2009, in turn driving 50% of CGI’s go-forward growth.

An essential role for the war rooms is to assess which changes are transitory and which are likely to be permanent—and to recommend actions for each. Temporary crisis behavior, like grocery stockpiling, may represent a closing window that requires rapid deployment to capture incremental revenue. More permanent behavior, however, often emerges where a preexisting trend or advantaged offering gets a crisis nudge—pushing consumers to trial new options, or resulting in a shift of cost-benefit tradeoffs. In the current crisis we already see candidates: telemedicine in health care, increased retail click-and-collect, more resilient supply chains, greater caution in travel and tourism, and normalized remote work. Capitalizing on these more permanent opportunities requires longer bets and capability builds, with historical examples able to inform companies today .

2. Outflank the competition. As business customers and consumers rapidly react to the terms of crisis, new brand perceptions, purchase behaviors, and demand patterns create competitive openings. Companies that capitalize on these openings faster than the competition can change the field of play in ways that reward beyond the disruption.

In the last recession, cost-conscious buyers began to delay new car purchases in favor of increased DIY maintenance and repair. Auto parts companies were implicitly positioned to benefit from this tailwind, but the spoils were shared unequally. AutoZone moved swiftly to expand its suburban demographic through investments in employee training and in-store technology. The company increased its private-label brand inventory to 50% of its offering, appealing to customers looking for low-cost parts. It also expanded video resources for DIY mechanics. A key rival of AutoZone pursued a less aggressive response. As a result, AutoZone grew at a 50% higher rate than this direct competitor and beat their shareholder returns by ten points in the three years following the recession.

3. Accelerate restructurings or investments. In normal times, major restructurings or investments, even when clearly advantageous, often stall in the face of tradeoffs and constraints. Revenue risk during transition, channel conflicts, or stakeholder inertia may delay action. A crisis, on the other hand, can lower barriers and opportunity costs, paving an easier path for action. Prior to the Great Recession, the US auto industry was faced with an inefficient and uncompetitive dealer network. While the “Big Three” automakers had long sought dealer consolidation, the recession and bailout opened a window of opportunity. Each manufacturer made sweeping moves. GM, for example, closed 40% of its 6,000 dealerships. Retained dealerships became larger, better managed, and more profitable as the industry experienced a decade of growth and margin improvement.

In the current pandemic lockdown, many valuable assets are idled, especially among retailers and businesses that are capital and fleet intensive. One countervailing benefit is the lowered cost of renovation and retrofitting. In this environment, companies can invest in value-boosting initiatives with a lower risk of sales forfeiture today than in the future—such as making stores attractive, lowering compliance risk, and enhancing production efficiencies. Stena Bulk, a European shipping company, recently announced that it is installing emissions scrubbers on 16 vessels to comply with newly tightened regulation. Scrubber investment is moving forward during a time of reduced shipping routes and staff.

Similarly, in the course of long-range planning, many companies contemplate attractive adjacent growth moves, only to sideline them in the shadow of a dominant core. Crises can shift this balance if the adjacency has better growth exposure once the crisis is over. In the last downturn, Aggreko, a mobile-power-generation company, saw a decline in the use of its equipment for events and construction. In response, the company swiftly shifted its focus from these applications to delivering emergency power generation in rapidly developing economies (RDEs), an on-trend shift aligned with RDE growth and the effects of climate change. These new geographic and application adjacencies increased sales from $1.2 billion to $1.8 billion in two years, and the company beat the S&P in value creation by nearly six-fold across the downturn.

4. Capture low asset values. In a crisis, the world goes on sale. Exhibit 2 shows the extent to which companies leaning heavily into M&A from 2007 to 2009 outperformed the market.

PepsiCo had long seen strategic advantage in buying back a network of independent bottlers for reasons of quality, channel investment, and coordination. Early in the last recession, PepsiCo jumped at the opportunity, acquiring the weakened network at a discount after it had seen a $2.5 billion year-on-year decline in enterprise value. The $200 million of cost efficiencies enabled by the move better positioned PepsiCo to weather the rest of the downturn.

Similarly, Macquarie Group, an Australian investment bank specializing in infrastructure, entered the same downturn with a healthy cash position compared to its potential targets. In 2010, it saw the opportunity for adjacent US expansion through a favorable acquisition of Delaware Investments. This led to a string of serial moves, which culminated in Macquarie’s transformation into a diversified investment bank and asset manager in a period when others retrenched. In this vein, companies should consider the full implications of M&A in the crisis of today .

5. Build a government affairs capability. As in prior crises, enormous stimulus packages and regulatory action are taking shape in response to COVID-19. Exhibit 3 shows how nearly $6 trillion in subsidies have been proposed across major markets thus far.

Meanwhile, regulatory regimes could unpredictably tighten or relax, from truck driver scheduling to food-labeling requirements. The likely magnitude, scope, and competitive impact of government influence argues for commensurate corporate engagement. Facing regulation or stimulus, companies must develop a firm ask from their government, as well as a credible narrative of how their actions are good for society, customers, employees, and the business itself. During the last recession, IBM advocated for relief under the American Recovery Act, helping to secure $30 billion for the technology sector. Following the act’s passage, IBM launched a $2 billion kick-start fund, extending loans to eligible projects, including a new health care service that enabled data exchange between physicians and patients. By 2013, IBM had received $180 million in stimulus awards.

Additionally, board members, too, have a role to play. Thanks to their varied backgrounds and contacts, each can help shape the message, create advocacy, and engage policymakers. Following 9/11, a $12.5 billion rescue package for airlines failed in the US House of Representatives. Within a week, board members from the six main US airlines engaged directly with congressional leaders—Congress promptly approved $15 billion in airline support.

A century of company performance shows that, in the fog of crisis, longer-term opportunity is both abundant and obscured. Companies that penetrate the mist, that see and seize the chance for transformational moves and investment, can find advantage in the fog. When it clears, they will look around and find themselves in the lead.