Unsurprisingly, the COVID-19 crisis has led to a big increase in e-commerce around the world. Wary consumers, many in lockdown, have been turning to online shopping in large numbers: during the third week of March, for example, e-commerce sales in the US were 58% higher than during the same period in 2019. Perhaps more telling, 20% of consumers in the US said that, over the previous 30 days, they had ordered groceries online for the first time ever.

We expect the shift to e-commerce to become permanent, with real consequences not just for online companies and their physical rivals but also for the companies that deliver all those purchases to homes and businesses. Right now, e-commerce-driven residential package deliveries are going strong, but more profitable B2B deliveries are down significantly, and increased costs to protect workers and customers have lowered profitability even further. Going forward, the surge in e-commerce may be challenging for delivery companies that are unprepared for rapid increases in volume and shifts in business models. But companies that can adapt to the new reality will benefit.

Turnaround Time

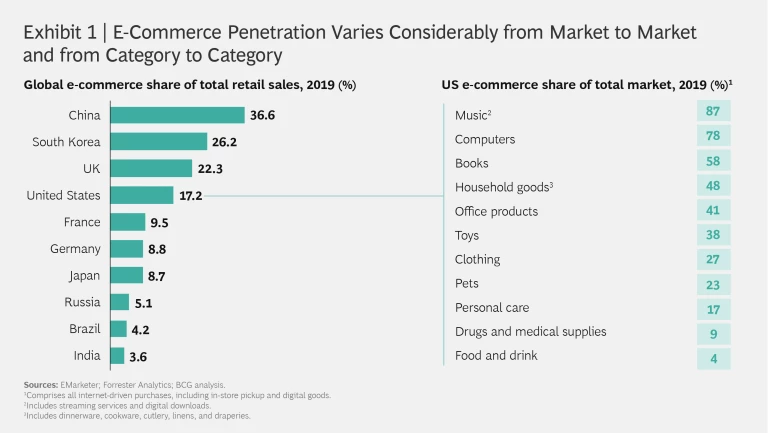

E-commerce had been growing impressively even before the onset of the pandemic. From 2017 to 2019, global growth in e-commerce sales outperformed brick-and-mortar sales by a factor greater than 10, and retail sales online were expected to rise from just 12% in 2017 to $6.5 trillion, or 22% of total retail sales, by 2023. Several major economies have adopted e-commerce with enthusiasm, including China, South Korea, and the UK; but large developing markets, including Brazil, India, and Russia, remain underpenetrated. Even in the US, the world’s largest economy, online sales had not reached 20% of the total before the pandemic, with such major retail categories as personal care, drugs and medical supplies, and food and drink notably lagging. (See Exhibit 1.)

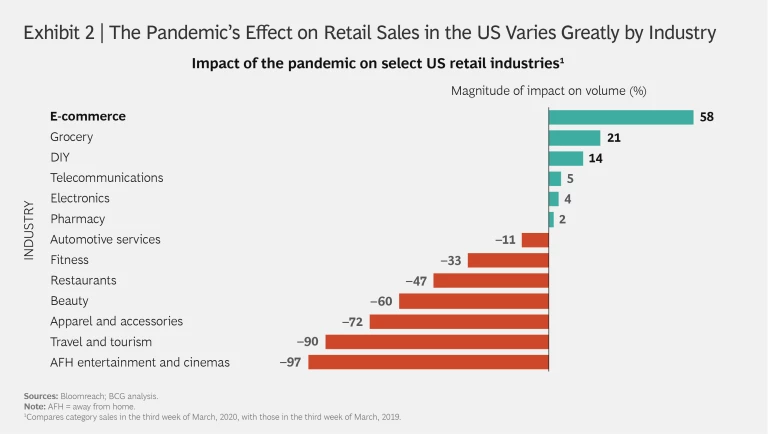

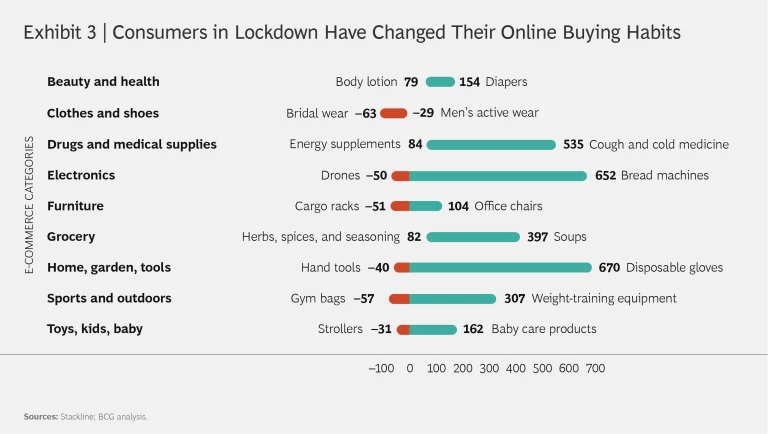

But that’s all changed. The impact of COVID-19 on the global economy has been swift, although it varies considerably from industry to industry. In the US, for example, entertainment outside the home, along with travel and tourism, is currently down by at least 90%, while grocery sales are up by more than 20% and e-commerce by more than 50%. (See Exhibit 2.) As a result, market capitalization for Amazon, the largest e-commerce player by far, has increased by more than 25% since the end of January. And first-quarter 2020 global revenues at Shopify, a Canadian provider of e-commerce services, grew by almost 50% compared with the same period in 2019. In the US, the increase in online shopping has led to booming sales in such categories as groceries, electronics, health care products, and toys, while clothing, sports and outdoor equipment, and other nonessential goods have suffered. (See Exhibit 3.)

Lasting Effects

But will the big uptick in e-commerce activity continue once the COVID-19 crisis ends? Thanks to the new buying habits that consumers are forming now, and the ways that businesses are adapting in response, we believe the answer to be a resounding yes, for several reasons.

The big uptick in e-commerce activity will continue even after the COVID-19 crisis ends.

Existing customers are increasing the frequency of online purchases, and new customers are buying online for the first time. As of mid-March, half of consumers in China, for example, had already purchased more goods online than they had in all of February. Half of consumers in the US said that they bought groceries online in March because of Covid-19 and approximately one-fifth of them did so for the first time. In Italy, the number of Carrefour’s online customers has doubled since the country’s lockdown began on March 9.

As more and more consumers discover the convenience of e-commerce, concerns about product quality and security will likely dissipate. Consumers have long preferred to judge the quality and freshness of the groceries they buy in person; that will change, now that so many are getting used to the convenience of food delivery. Target, a US department store chain, reports higher levels of spending and loyalty among its new online customers. And the introduction and use of mobile apps tracing the progress of the COVID-19 outbreak have shown that personal data can be used and stored safely, removing concerns about the security of online shopping.

Another factor lies in the sheer number of retail stores likely to close as a result of the pandemic, making it that much harder to purchase goods offline. Experience in China has already shown that even after the lockdown there lifted, consumers are not rushing back to physical shops. This will force all kinds of businesses to reinvent themselves online. Chinese retailer JD.com, which sells both online and in physical stores, is partnering with consumer brands to offer promotions and extending same-day delivery to smaller cities and other new markets. Uber Eats and Deliveroo are rapidly recruiting new restaurants to their delivery services. And even categories that are already doing well online in certain markets, such as fashion in the UK, will likely reach levels that are higher still.

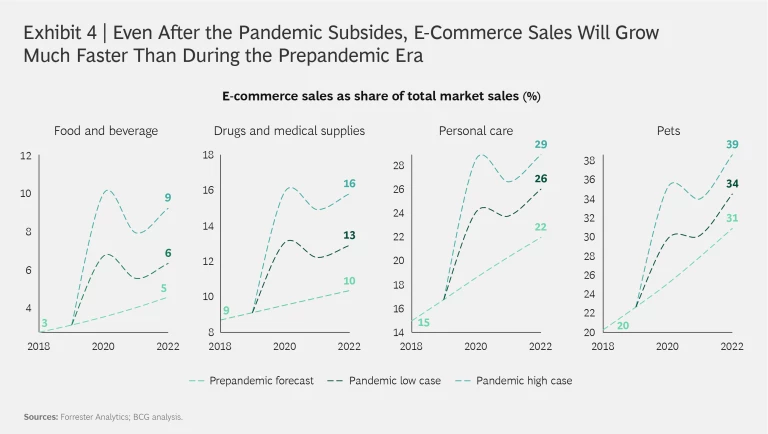

Our analysis of four key consumer categories—food and beverage, drugs and medical supplies, personal care, and pet products—suggests that online sales as a percentage of the total will continue to grow far faster than prepandemic estimates, even after the crisis ends. Sales of food and beverage products online, still just 3% of the total, are likely to make the most gains—a major shift, given the sheer size of the market. But we estimate that even online sales of pet products, already 20% of the market, may grow to as much as 39% over the next two years. (See Exhibit 4.)

In short, the pandemic will bring major increases in online penetration to virtually every product category, no matter how large the online sales are now.

The Shipping News

Despite the increase in business for e-commerce, the key sector on which it depends—the delivery companies—have struggled. The market capitalizations of many of the largest companies—including Deutsche Post DHL (DPDHL), FedEx, and UPS—have declined by 15% to 30% from January to mid-May, significantly more than the 12% decline in the S&P 500 index over the same period.

Every element of the global transportation network has been under siege because of the pandemic.

The reasons aren’t hard to find. Every element of the global transportation network has been under siege over the past few months because of the COVID-19 crisis. Right now, most ocean cargo, for example, has been rerouted around Asia; shipping capacity on routes between Asia and North America was down 26% in March, compared with last year; and ships leaving Chinese ports are at as little as 10% capacity. Lost trips due to reductions in Asia-to-Europe shipping routes has also led to lost revenue from return trips, negatively impacting the financials of the ocean cargo transporters even further.

Every major airline has shut down routes and other aspects of their operations. Multiple US and international airlines have suspended or reduced all passenger flights to China, Europe, Japan, and elsewhere: 1 million commercial passenger flights have been canceled through June 30. Fully half of the global air fleet and 30% of the global air cargo fleet have been grounded, resulting in a severe shortage in airfreight capacity and quadrupling the costs—to as much as $1 million per day—for one-way charters of full freighters.

To make up for the added costs, some intercontinental express companies are imposing temporary surcharges on customers and shutting down select routes entirely. Meanwhile, several passenger airlines, including American Airlines and Korean Air, are converting some of their otherwise grounded planes to cargo-only carriers and delivering critical medical supplies, foodstuffs, and other essential goods.

The impact on individual companies has varied, as have their responses:

- Overall, DPDHL remained profitable in the first quarter of 2020, but surging growth in e-commerce parcels was offset by a double-digit reduction in mail volume. As a result, the company’s first-quarter earnings declined by $260 million, $100 million of which came out of the operating profits in its Express division. The ongoing uncertainty forced the company to withdraw its earnings forecast for 2020. It also delayed payment of DPDHL’s annual dividend to conserve cash needed to fund its German postal operations and to meet the higher-capacity requirements for e-commerce parcels. In addition, it stopped shipping small parcels from Germany and other European countries to Brazil, China, North America, and elsewhere, and is charging businesses an “international crisis surcharge” of €16 per package shipped to the US.The US Postal Service announced that the sudden drop in mail volume has led to a severe cash crisis. It expects to run out of cash by September 30 without further financial assistance from the government and predicts a near-term, pandemic-related loss of $13 billion, which is expected to rise to $22 billion over the next 18 months. As a result, it has asked the government for $75 billion through a combination of cash, grants, and loans to avoid a liquidity crisis in the fall.

- Like DPDHL, FedEx has stopped issuing earnings forecasts and is taking measures to protect its cash flow and liquidity. To that end, it has borrowed $1.5 billion to build up its cash reserves, stepped up ongoing cost reduction measures, and introduced temporary surcharges on all international packages and airfreight shipments. Meanwhile, higher demand for FedEx Ground retail deliveries has been offset by weak demand for global B2B transportation, forcing the company to reexamine its overall operations.

- Several carriers, including FedEx, UPS, and DPD UK, have imposed temporary surcharges on packages sent to select destinations to partially offset increases in transportation costs due to the severe shortage of intercontinental air capacity. And Amazon has suspended delivery of items from its third-party e-commerce partners entirely.

Some companies, however, are thriving. The market capitalization of SF Holding, a Chinese delivery company with no real competition in its home territory, has risen by almost 50% since the beginning of the pandemic. Its business model is focused almost exclusively on e-commerce, and its delivery volume rose by more than 40% in January, the first month of the COVID-19 crisis in China.

What to Do Now

SF Holdings, however, is an exception. Few other companies have been able to benefit from the nearly 60% rise in e-commerce over the past few months; indeed, their capacity has been reduced, revealing gaps in their delivery networks. On the business side, for example, grocers are blaming their distributors and the delivery companies with which they work for the shortage of vehicles, drivers, and workers, and the lack of adequate storage space, resulting in more empty shelves. What’s more, the rapid rise in residential demand is proving to be economically challenging for deliverers that must rebalance their operations away from more profitable business delivery.

Several delivery companies are already taking steps to rethink their operations and revive their short-term fortunes.

Several delivery companies are already taking steps to rethink their operations and revive their short-term fortunes. As noted above, some companies—including Amazon, FedEx, and DPDHL—are adjusting their agreed-upon service levels; increasing shipping time estimates for some customers, depending on the nature of the products ordered; and temporarily suspending service in some locations, depending on the severity of the pandemic. They are also boosting the use of warehouse robotics to streamline and speed up order fulfillment.

Furthermore, and in addition to Amazon, others—including Alibaba and JD.com—are also hiring employees from other sectors, setting up online job-sharing platforms to attract unemployed workers, and increasing pay for warehouse and delivery workers—by as much as $2 an hour in the case of Amazon. Alibaba and SF Express are also turning to robotics to streamline warehouse operations and speed up order fulfillment. To manage the rise in complaints about delayed and missing packages, companies are shifting away from call centers and partnering with consumer brands and restaurants to improve their chat and other online customer service methods.

All delivery companies are taking safety precautions and increasing hygiene in operations—forgoing routine signatures for package delivery, regularly sanitizing delivery equipment, and adjusting processes and training employees and third parties to comply with safety requirements.

In hopes of maintaining, and potentially expanding, operations during the current crisis, delivery players can boost their advantage in several ways:

- Creative Delivery Methods. Expand the use of noncontact delivery methods, such as lockers and pickup points. Ensure real-time tracking and communication with customers to help minimize disruptions.

- Control Tower for Rapid Response. Set up a rapid response unit with 360-degree visibility into operations to provide reliable information to customers. Plan joint business operations with key clients to ensure closer coordination with customers.

- Talent Upgrade and Qualification. Take advantage of the market downturn to fill positions in strategic areas, such as IT. Develop structured temporary hiring programs to respond better to surges in demand. Implement programs to qualify employees to work not only during the crisis but also after it is over.

- Dynamic Pricing. Analyze capacity constraints and their impact on service levels, and use dynamic pricing strategies to smooth supply chain bottlenecks during the crisis.

- Personal Connection with Consumers. Develop a personal connection with consumers, allowing them to set up preferences and inform them of good delivery practices. Educate them about the safety and convenience of online shopping and delivery.

The Recovery Process

In just a few months, the COVID-19 pandemic has transformed how we live, work, and shop—at least for the time being. As of now, it’s unclear which changes will prove to be the longest lasting. There’s no doubt, however, that the impact on e-commerce will linger far into the future. The choice, convenience, and immediacy offered by online shopping have proved essential to consumers around the world and will likely accelerate its acceptance in virtually every product category.

The impact on delivery companies, however, has been mixed, with many struggling to keep up with the increased volume amid major challenges to their operations. Yet they, too, will recover and benefit from the increasing shift to e-commerce. To get ready for this new world, they must expand their operations, improve their logistics technology, and increase their efforts to boost efficiency through automation.