Not long ago, a small contingent from a company’s change management office was dispatched to a remote field operation. The purpose of the trip was to ensure the adoption of new digital processes. The meeting was not a success. The field managers—many with decades of experience in their disciplines—didn’t like the new processes and didn’t see why they should adopt them. The change management team returned to headquarters fearing the resistance they had encountered would derail the program. It still may.

Companies that want to endure must be skilled at transformation. There are a lot of reasons why so many of the companies that were on the Fortune 500 list 25 years ago have disappeared from it. However, one common thread is a failure to adapt. Often the failure isn’t a matter of vision but of execution. An effective approach to change management is especially important today; the coronavirus pandemic is testing the adaptive skills of every organization.

The coronavirus pandemic is testing the adaptive skills of every organization.

Mistakes in change management follow a few familiar patterns. Some companies form their change management units for specific projects at the last minute and do not clarify the role that they expect the change management team to play. Other companies focus primarily on the communication plan and don’t take the time to think through the impact that a set of new behaviors will have on their organizations.

Still other companies outsource their change management functions, or staff them with relatively junior people. In some cases, the change management team institutes operational changes directly—with the best of intentions—but doesn’t secure a department’s buy-in. The changes feel “bolted on” and don’t last.

Over the course of hundreds of client transformations, Boston Consulting Group has identified ways to minimize these problems—and strengthen companies’ change management functions.

Three actions are crucial:

- First, ensure that the role of the change management function evolves to suit the various stages of the transformation program.

- Second, develop the handful of traits that are critical for any effective change management function.

- And third, pick an organizational structure for the change management function that has the right mix of centralization and decentralization.

The Role Must Continuously Evolve

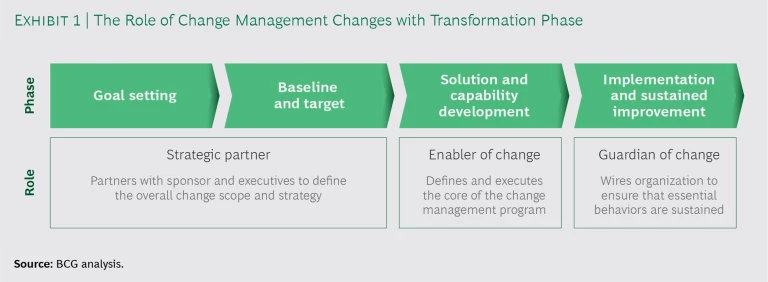

The life cycle of a typical transformation comprises four phases: a goal-setting phase; a baseline and target phase (for determining where the organization is and where it needs to end up); a solution and capability development phase; and an implementation and sustained improvement phase. The role and composition of the change management function should evolve from phase to phase.

Let’s take a hypothetical example of a multibillion-dollar company that has decided to remove costs throughout its global operations. In the goal-setting phase, the change management team functions as a strategic partner. This begins with getting a clear picture of the magnitude of the reductions.

Because this is a high-level strategy discussion—usually involving the CEO and the CFO—the change management team should be more senior and relatively small. A big part of the change management team’s job in this phase is to clarify unit leaders’ roles in the transformation and start to equip those leaders for the journey to come. This includes defining the change management method and approach—whether developed internally or with the help of external partners—and describing the tools that the organization will employ.

The strategic partner role continues into the baseline and target phase, when more specific goals are set. (See Exhibit 1.) For instance, the company may have decided it must lower its overall costs by 20% and may have made some initial decisions about the cuts that will come from individual business units, functions, and geographical locations. The change management team’s job is to anticipate the organization’s response to these high-level goals and come up with a plan that addresses the challenges and increases the odds of a smooth transition.

For the solution and capability development phase, the change management team’s role becomes one of enablement. This is when many of the most challenging transformation activities take place, including engaging employees, encouraging them to cocreate solutions, identifying and addressing areas of resistance, and getting people to adopt new ways of working. This is also the time when training curricula are put together and when KPIs and scorecards start to be used in tracking progress.

In this phase of a transformation, the change team’s span of influence needs to expand beyond the executives and leaders it focused on previously. Its influence now touches the entire organization. For this to work, the change management function generally needs to grow in size and become embedded in individual businesses and functions. The change management staffers who work in these local hubs need not be as senior as those who participated in the initial strategy phases. But the staffers do need to be conversant with the change agenda and tools, skilled at training and coaching, and knowledgeable about the business areas they are helping.

In the final phase—implementation and sustained improvement—the change management function assumes the role of a guardian. Its job is to make sure that the individual departments continue to use the new tools, practices, and work approaches that were put in place, and to set up the measurement systems that will guard against backsliding. The local change management hubs start to shrink at this point and may even disband once the changes become ingrained with workers.

Traits of Effective Change Management Functions

The evolving role that change management takes can help companies minimize the people challenges that routinely crop up in transformations. But for some other challenges—like keeping track of the multitude of moving parts—some key traits are needed. We find that the following traits are always present in a good change management function:

- A Consultative Approach with Senior Leaders. We have already alluded to the negative effect that skeptical or uncooperative leaders can have on transformations. The transformation agenda and all transformation-related tools and approaches need to be backed by leaders. It’s up to the change management function to increase the odds of this happening. Part of this involves persuasion—getting senior leaders to buy into a transformation agenda—and part of it involves coaching. Transformation management doesn’t come naturally to many executives. Most of them need some coaching to become effective change agents and to understand the behaviors they need to model and cascade throughout the organization.

- High Levels of Skill and Experience. Managers aren’t always wrong when they react negatively to the directives coming out of change management units. We have seen many situations where change management staff members are too junior or have the wrong backgrounds for their positions. The people in change management functions should be accomplished in their own right or be recognized as individuals on their way up in the company. A mix of external and internal talent is often needed to get the change management initiative off to a good start.

- An Employee-First Change Approach. At some point in a transformation—certainly by the implementation phase—the responsibility for making it work shifts to everyday employees. Because of this, there must be multiple mechanisms for engaging employees. If a company expects to get the benefits of workers’ insight and creativity, it must put employees at the center of the change. Otherwise, the new target state—whether it’s related to savings or top-line revenues—will be harder to achieve and sustain.

- A Clear Change Management Operating Model. Individuals need to be held accountable for change management activities and outcomes. This only happens if there is accountability in the right places in an organization—invested with the right executive, business unit, or function. Effective change management functions encourage others to execute change management activities, rather than always seeking to handle the activities themselves. They make these assignments concrete through tools like responsibility assignment matrices (RACI charts) and central change management “control towers” (our term for digital systems that track progress).

Four Organizational Structures

Transformation programs have any number of objectives—examples include digitizing back-office operations, implementing new technology systems, integrating sales forces with an acquired company, and improving innovation performance. Indeed, at a big company, many transformation efforts could be underway simultaneously.

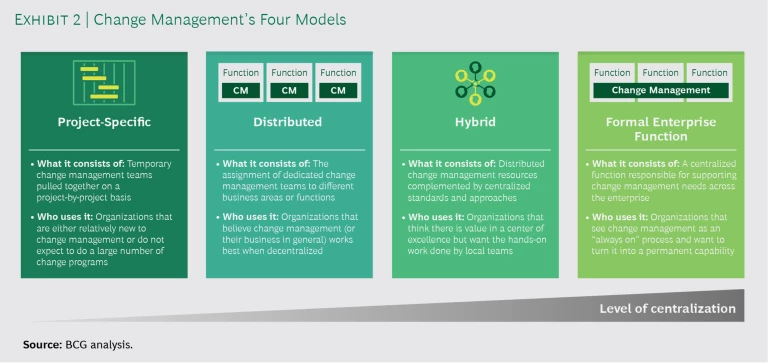

Four basic organizational structures for change management have emerged. (See Exhibit 2.) The structure that a company adopts may reflect its sense of how frequently it’s going to need to transform. Or it could reflect a company-wide bias toward centralization or decentralization.

The four structural options are as follows:

- Project-Specific Change Management. In this approach, organizations pull together temporary change management teams to implement specific transformations—say, the rollout of a new financial system. After the project is completed, the teams disband and the individuals in them resume other roles.

- Distributed Change Management. Companies with multiple, simultaneous transformations may handle the different initiatives separately. (If there is enough geography separating them, the teams responsible for the transformations may not even be aware of each other.) This ad hoc approach has the advantage of speed but the disadvantage of not adding to the enterprise’s core change management knowledge.

- Formal Enterprise Change Functions. Organizations that opt for this structure maintain central change management teams with dedicated personnel. Companies often use this structure when they are at the beginning of a prolonged period of change and realize that a central change management capability could help when multiple transformations must happen simultaneously. The centralized teams operate as centers of excellence, developing methodologies and best practices that can be applied across different change programs.

- Hybrid Structure. In this structure, centralization and distribution coexist. The focus of this “hub and spoke” approach can be adjusted, with the hub being stronger in a multiyear transformation that affects the entire enterprise and the spokes being stronger in a simpler transformation, such as one involving the institution of new travel reimbursement procedures.

Companies usually default to project-specific change management when they’re first doing transformations. Formal enterprise change management, with centralized resources, often comes next, when companies have multiple transformations in the pipeline and are seeking to build out a permanent change management capability.

However, companies with the most experience doing transformations often distribute their change management function, placing their change management people in the locations and business units where the transformations are happening. Arguably the most sophisticated distributed structure is the hybrid type, which has both a central brain trust to offer high-level guidance and “arms” (in the form of distributed staff) to help with execution. We’ve found that the hybrid structure does the best job of ensuring development of long-term change management capabilities.

Organizational transformations are complex by their nature. Once they get going and start affecting people and processes, there is never a moment without some sort of hitch.

Effective change management functions are able to adjust the role they play as transformations advance from phase to phase, cultivate proven best-practice traits (including an employee-first approach), and know which parts of their change management organization to centralize and which parts to distribute.

There’s always going to be someone, at some point in a transformation, who is standing in the way. With the right change management elements, there will be fewer obstacles to overcome.