Family-owned businesses are employers of millions of individuals globally, generators of sizable streams of tax revenue, and financial and social anchors for many communities. The families that own these businesses typically exert considerable influence over their management and operations and, as a result, their performance and survival. The decisions that these families make impact their wealth as well as the futures of the people they employ and often the ecosystems in which they operate.

Without guidelines that govern decision making, families may struggle to agree on leadership choices, succession issues, and other contentious topics that can have a substantial impact on their businesses. It is therefore important that families create an operating model that is tailored to their businesses—a model that helps them manage effectively, treat family members fairly, and preempt conflict.

The Economic Importance of Family Businesses

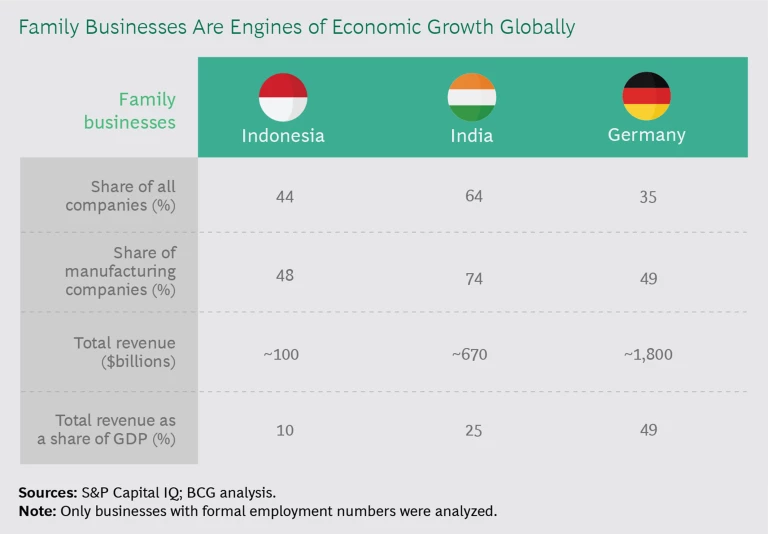

The role that family businesses play in advancing economic growth is hard to overstate. (See “An Economic Bedrock Through the Ages.”) In many major economies, family-owned businesses account for a significant share of all companies. Our analysis of Indonesia, India, and Germany found that family businesses represent 48% to 74% of all manufacturing companies. (See the exhibit.) They also create millions of jobs through direct employment and millions more indirectly. And they inject significant revenue flows into these economies. In Indonesia, family-run businesses generate more than $100 billion (roughly 10% of GDP). In India, that figure climbs to nearly $670 billion (about 25% of GDP). And in Germany, family businesses contribute a massive $1.8 trillion in revenue (approximately 49% of the country’s GDP).

An Economic Bedrock Through the Ages

Family businesses helped fuel the prosperity of the early Chinese, Egyptian, Greek, Persian, and Roman civilizations. The philosopher Aristotle even wrote a treatise touching upon how these businesses should be managed. In time, family apprenticeship models gave rise to guilds focused on specific trades. The family enterprises represented by these guilds helped shape economic growth from the Middle Ages through the Industrial Revolution. Family businesses continue to play an important role in advancing economic growth in both developed and developing parts of the world today.

The role that family businesses play in promoting prosperity is not well understood by many governments and regulators, or even by the families themselves.

Because family businesses help support ecosystems—creating jobs for family members and employees, revenue streams for suppliers and governments, and stability for their surrounding communities—the failure of these enterprises can have catastrophic implications on economic growth, especially in emerging markets. Yet, the role that family businesses play in promoting and protecting prosperity is not well understood by many governments and regulators, or even by the families themselves. In fact, in some emerging markets, governments and the broader population often resent family business owners because of their wealth—and because of behaviors that seem to flaunt it.

Family businesses come in many different sizes, from small mom-and-pop entities to major regional companies and even global enterprises. Some families serve as owner-managers, a model that is especially common in emerging markets such as India and Indonesia. Other families function as activist investors: one or more family members sit on the company board and provide an ownership perspective on strategy, capital allocation, and management performance. Still others operate as large but passive shareholders, supported by family offices that manage investments and dividend allocations.

Given the variety of ownership and management structures and the needs of different families, it can be hard for families to determine what type of governance, if any, to adopt. The unique nature of family businesses can also make it hard for those seeking to advise or partner with them. (See “What Potential Partners Need to Know.”)

What Potential Partners Need to Know

Such soft issues and qualitative factors can increase the level of risk for those that partner with a family business. Banks and investors, for example, should not evaluate a family enterprise by relying solely on traditional criteria, such as financial metrics. A business that looks good on paper, for instance, may look very different when family dynamics are factored in. As part of their due diligence, potential partners should consider the following questions when deciding whether to work with a family-owned enterprise:

- Who runs the business? Potential partners need to know who the ultimate decision maker is. Is it the CEO or chairperson (who may or may not be from the family), the head of the family, or even a group of family elders who are not directly involved in running the company? Potential partners also need to be sure that they understand—and are comfortable with—the decision maker’s priorities and business mindset. Partners should consider entering into a business relationship only if they and the decision maker agree on the expectations.

- What is the family’s reputation? Because families in business may have more informal networks than corporations do, potential partners may need to go beyond traditional financial background checks to evaluate the family’s reputation. Assessing the success or failure of past joint venture relationships, or evaluating the family’s history of healthy or rocky business dealings by talking to other business contacts, can help potential partners gauge matters of trust and dependability.

- Is there a clear view on succession? A lack of agreement on succession planning is one of the biggest sources of family conflict and the one with the greatest potential to destroy value. Before entering into a relationship, potential partners should determine if a clear succession plan is in place; if not, they should consider whether this is a risk they are willing to take.

- How strong are underlying capital markets? Access to capital and financial liquidity can vary greatly across markets, affecting an investor’s ultimate exit strategy. For example, it is generally harder for a private equity investor to sell a stake in a family business in an emerging economy (where capital markets are less well established) than in a developed economy. Potential partners should factor in local market characteristics when evaluating family businesses.

Unclear Rules and Expectations Expose Families and Their Businesses to Risk

Most nonfamily-owned businesses start out with a handful of people and a loose operating structure. As these businesses grow and bring on new people and investors, they begin to adopt more-formal management structures that articulate ownership rules, decision-making rights, and codes of conduct. These businesses also establish steering and oversight committees that help them run more efficiently. And the legal structure that they adopt—a corporation, for example, or a partnership—subjects them to statutory requirements, such as a formal business charter, an official code of conduct, a board of directors, and other governance norms.

Nearly all families can benefit from establishing an operating model that guides their involvement.

Family businesses evolve similarly, adopting the same management and governance structures that are statutorily required of them. However, family owners tend to neglect structures and rules that govern the family’s own engagement in the business because these are not legally required. But without agreed-upon operating norms, families have little to guide them when conflicts arise. Resulting disagreements can sour relationships and even prove fatal to the business if no effective resolution is found. For this reason, nearly all families can benefit from establishing an operating model that guides their involvement in the businesses that they own. In some cases, a strong family head can define a set of norms that become the de facto family operating model. In other cases, where multiple family members have decision-making roles, the family may wish to bring in external advisors to help define a model. What’s most important, however, is that family members agree on how to manage the business.

A family should take the following four steps when defining an operating model.

Agree on the Family’s Overarching Goal

To implement effective governance, the family should clarify its overall business priority. As the owner, the family has the right to run the company in the manner it feels is most appropriate, but as the manager, it is accountable for delivering sustainable value and growth. The family must therefore decide if its overarching priority is to build a great business, maximize wealth for the family, or put family first by creating opportunities for this generation and future ones. (See “Different Inheritance and Wealth Models Have Different Requirements and Implications.”)

Different Inheritance and Wealth Models Have Different Requirements and Implications

Under the Greek inheritance model, the family accepts that the share and wealth of individual members will become diluted with each new generation. Unless planned for in advance, this model can lead to a complex and fragmented ownership structure that can eventually cripple the business’s ability to function as the number of family members grows. Families have several options to address the ownership issues that can result when there are many family members. For example, they can split the business, exit the business, allow family members to become passive shareholders, or create rules that allow multiple family members to manage the business together. Whatever the approach, it is crucial that families get the advice needed and choose one clear path to avoid additional issues later.

Under the primogeniture model, ownership and control are vested in one individual, often the eldest child, although ownership could also be vested in an individual elected by a family council or outside body. Siblings are often well provided for in such arrangements, and many gain luxurious livelihoods. Although this model has become less popular in modern times, families that opt for this approach must define succession-planning guidelines and decision rights to ensure smooth transitions from one generation to the next to reduce the risk of conflict.

Under a wealth-first model, a family generally behaves as a fund manager and looks to maximize long-term returns. The family may choose to run the business, or, very often, it will turn to external managers. Although this model has the fewest emotional strings attached, it also has the least direct control. Families that take this approach need to determine how engaged they want to be in the day-to-day oversight and management of their businesses.

As with any business, there are tradeoffs. A business-first goal may advance the bottom line, but it may also restrict opportunities for family engagement. Likewise, a family-first mindset allows for deep engagement across the extended family, but it can create an exclusive atmosphere that may prevent the company from attracting outside talent with the skills and expertise needed to compete effectively. The family needs to settle on the business priority that best complements its values and take a unified, explicit stance. This decision will inform the business strategy and operating principles.

Anticipate Potential Hot Spots

The family needs to anticipate typical flash points that may derail the business’s success and jeopardize family harmony. Because it can take a long time to rebuild relationships, family members need to be alert to sensitive topics. Issues that can lead to conflict include leadership choices, wealth sharing among family members, and decisions related to running the business. Disagreements can be intergenerational (between parents and their children, for example), intragenerational (between siblings and cousins, for example), or even between a married couple when both are involved in the business.

In the absence of an agreed-upon operating model that addresses the difficult topics, conflicts can escalate. Family members may delay discussing differences of opinion or refrain from initiating conversations around business or management issues lest they be perceived as sowing seeds of discord. When differences are not aired and issues are not resolved, communication among members or branches of the family can deteriorate rapidly. Factions can form, and disagreements can spill over into day-to-day interactions. Anticipating and addressing points of conflict early on, and treating them with sensitivity, can protect the business as well as the family.

Review the Context in Which the Family and Business Operate

No two families or businesses are alike. Families need to take context into account when designing the appropriate operating model by examining three elements.

Ownership Structure. Family members should get a baseline understanding of the current (and future) ownership structure. For example: Is ownership concentrated among a few family members or many? Are there two or more potential successors? Is current leadership near retirement age? Are family members deeply involved in running or overseeing the business, and do they want to be? Are members of the next generation capable of and interested in running the business? The answers to questions such as these can confirm existing norms and help decide if the family’s engagement structure with the business should change.

In the absence of an agreed-upon operating model that addresses difficult topics, conflicts can escalate and factions can form.

Nature of the Underlying Business. Family members must understand the underlying business. Do they own more than one company? Do they own a publicly traded company? Do they own a company that operates in more than one industry? How easy or difficult would it be to split up the company?

Characteristics of the Local Ecosystem. Family members need to assess the maturity of local capital markets, societal expectations, and the regulatory, legal, and tax constraints of the jurisdictions in which they operate. These parameters will affect how the business can grow and develop within its ecosystem.

Create Structure for the Family

After agreeing on the overarching goal, anticipating potential hot spots, and reviewing the context, the family should decide on a governing structure. The degree of formality can vary. Generally speaking, the structure consists of a shareholders’ agreement, a description of governing bodies, and a family code of conduct.

Shareholders’ Agreement. Although small family businesses and those operated for only one or two generations may not need an explicit shareholders’ agreement, all families should, at a minimum, gain consensus on three points:

- The Definition of Family. Blood relatives are easy to classify as family, but family members often have differing points of view on how to classify in-laws, adopted children, stepchildren, and others. Establishing criteria that clarify who is and is not family is crucial.

- Rules for Owners. Family businesses should clarify the rules that owners must accept. Specifically, the rules should stipulate whether shares will be held by individual members or a trust. Both options come with legal and tax implications that must be carefully evaluated. The rules should also spell out if an owner’s stake can be willed or transferred to family members or nonfamily members. Exit guidelines for family members who wish to leave the business should also be detailed.

- Rules for Managers. Families should detail what criteria members must meet to enter the business, when family members must retire, and specific instructions on whether senior roles in the business are to be reserved for the family.

Governing Bodies. Formal governance structures become more important as the number of family members involved in the business grows. Small families or those that have a relatively new business can make decisions informally, as long as family members are in agreement. Larger families often benefit from establishing two governing bodies to manage the family’s interests: a family assembly and a family council. These are in addition to committees that help run the business.

Larger families often benefit from establishing two governing bodies: a family assembly and a family council.

The family assembly is often quite large, comprising all family members who have an ownership stake in the business and sometimes even those who do not, such as children and spouses. The family assembly is responsible for key activities, including selecting members to the family council, assigning decision rights, and establishing broad parameters under which the council operates.

The family council is smaller than the family assembly. Because the council’s primary function is oversight of the family’s business affairs, it is also vested with decision-making authority regarding those matters. The family council functions like a board of directors, and the chairperson is usually a senior family member. The council has responsibility for making major decisions that impact the family and the business, such as selecting the CEOs for portfolio companies from within the family or deciding the amount of annual dividend payouts. Council members are elected through a vote in the family assembly and serve for fixed terms. Given the power held by the family council, we recommend the following best practices:

- Ensure representation from all branches of the family.

- Set clear eligibility and operating rules for the council, including ones for term limits, member selection, and membership voting and impeachment.

- Define the role of the chairperson and ensure consensus on selection rules.

- Establish checks and balances so that the family council is answerable to the family assembly and must regularly communicate decisions to it.

- Enable the family council to seek advice from external advisors when required.

Family Code of Conduct. A code of conduct is essential for all family businesses, regardless of their size. It is arguably the most important document in keeping the peace among family members, since most conflicts tend to arise over the nature and manner of interpersonal interactions, rather than a specific business topic.

In essence, the code of conduct is a set of rules that describes how members of the family are expected to behave when they interact and talk with one another—and with the public. The code must emphasize how family members should air any issues and the mediation process to resolve them. It may also lay out expectations concerning lifestyle and behavioral choices that family members can lead, especially with respect to overt displays of wealth. (See “Families Need to Be Sensitive to Income Inequality.”) Penalties for violations of the code must also be detailed. A thoughtful code of conduct can be the difference between a swift, private, and amicable resolution and a protracted and public legal battle.

Families Need to Be Sensitive to Income Inequality

Recent years have seen widespread protests erupt in various places around the world, including Brazil, Chile, France, and the US. Individuals in both the developed and developing world are expressing dissatisfaction with political and capital systems that seem to reward the wealthy and leave the poor behind.

Because family businesses play an outsized role in many domestic economies, particularly in the developing world, they need to be especially alert to these trends. The narrative around their success—particularly if the business is large and influential—may not be viewed favorably by the rest of the population, especially if that wealth is flaunted. In an age when social media can amplify news and popular sentiment, images of lavish weddings and palatial homes can breed resentment. Families need to be sensitive to how they portray themselves publicly and reinvest gains in ways that benefit both the business and the broader community.

Family businesses are an important driver of economic growth, especially in emerging markets, where the ability of these businesses to take on risk has resulted in jobs for family members and employees, revenue for governments, and stability for communities. However, managing family businesses is complex, given the close personal and professional relationships involved. Establishing governance rules and setting expectations can help protect the growth of family businesses and their ecosystems for generations to come.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.