In health systems around the world, hospital leaders are increasingly looking beyond the walls of their own institutions. They are considering—and, in some cases, actively pursuing—strategies of combination in which they partner with other hospitals to improve economies of scale or extend the scope of service delivery.

The most dramatic example of this trend is outright consolidation, the merger of independent hospitals into ever larger organizations. According to a November 21, 2019, article in the Economist, 90% of US hospital markets—representing a population of more than 200 million people—are now highly concentrated. But formal consolidation of ownership is far from the only (or, in many countries, even the main) form that these combinations take. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of partnership types—joint ventures, alliances, collaboratives, various group models, and the like.

What’s driving the combination trend? In the past, hospitals have used combination primarily to cut costs and improve their pricing power in negotiations with payers. Although such a strategy can enhance the competitive position of hospitals vis-à-vis other stakeholders, it does not necessarily boost the value delivered by the

health system

as a whole. As noted in the Economist, in the US, prices at hospitals that enjoy a local monopoly are approximately 12% higher on average than in markets with four or more rivals. While consolidation has cut costs by 15% to 30%, average prices rose by 6% to 18%. And according to recent research, US hospital mergers and acquisitions are associated with modestly worse patient experiences and no significant changes in key health outcomes metrics such as readmission and mortality rates.

Combination Done Right

When done well, however, combination can generate substantial value for the entire health system—by lowering total system costs, providing better quality of care, and encouraging the rational integration of care delivery. Combination can be an effective way to improve

How to Define Health Care Outcomes

by consolidating volume for specialized procedures.

For all these reasons, the trend toward combination is likely to continue and, over time, become increasingly focused on health system rationalization and greater integration of primary, secondary, and tertiary care. In theory, hospitals are well placed to lead this effort. Integration of care delivery requires strong leadership and a concentration of resources and talent. In most health care markets, those capabilities are found in hospital institutions.

In the process, however, hospital CEOs will face a series of complex strategic choices. They will need to decide whether to combine with other entities in the local health system, how to do so, and with which partners. Some will actively embrace combination as a strategic imperative; others will be forced to do so in response to the moves of other players (including payers, who in many countries are taking an increasingly active role as drivers of health system integration).

Integration of care delivery requires strong leadership and a concentration of resources and talent—capabilities that are often found in hospitals.

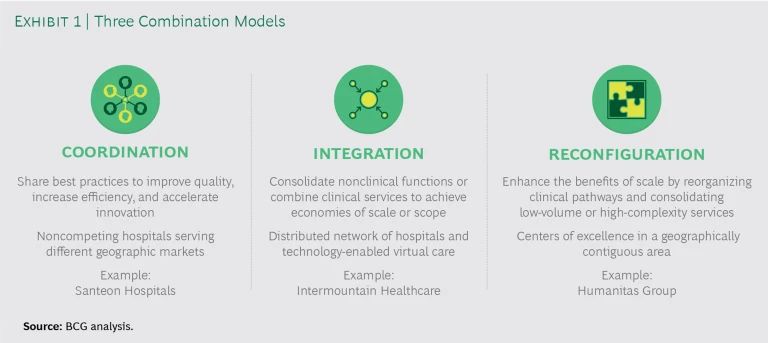

Three Varieties of Combination

The starting point is to realize that different types of combinations may or may not be appropriate depending on a hospital’s service delivery context, existing capabilities, and strategic goals. These types can be mapped along a spectrum from relatively loose coordination among independent hospitals to the institutional integration of nonclinical and clinical activities to the wholesale reconfiguration of clinical pathways in a local health system. (See Exhibit 1.) Depending on a hospital’s situation in its local market and the context of its national health system, it may decide to pursue one or more of these versions of combination simultaneously or evolve through them over time.

Coordination

The simplest form of combination involves independent organizations sharing best practices to improve quality, increase efficiency, and accelerate innovation in care delivery. In the Netherlands, for example, seven Dutch teaching hospitals have joined together in an association known as Santeon to improve patient care by fostering interhospital cooperation.

In 2016, the Santeon hospitals launched a joint program to improve care delivery, initially focusing on five target patient groups—those with breast cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, cerebrovascular accident, and hip arthrosis. The independent executive committees and medical staffs at the seven hospitals made a joint commitment to “realize better outcomes for patients faster together” through transparency on health outcomes and costs. The hospital leaders also committed to a long-term agenda: developing and testing a structured methodology for continuous improvement, first with the target patient groups and then expanding it to include additional groups.

The evidence to date suggests that Santeon’s value-based program is having a major impact on both patient health outcomes and system costs. Take the example of breast cancer: the hospitals have reduced the annual rate of lumpectomy reoperations resulting from positive surgical margins (a sign that some cancer cells may remain after surgery) by 17%, on average, across all seven hospitals and by up to 64% at the hospitals that put in place dedicated improvement initiatives. Similarly, reoperation rates related to postoperative complications after lumpectomy dropped by 27%, on average, with a single-hospital high of 74%. On the basis of these results, Santeon recently became the first health care organization in the Netherlands to negotiate value-based contracts with Dutch insurers for the treatment of breast cancer.

Integration allows institutions to benefit from economies of scale and can be a way to expand a hospital’s clinical offerings.

As the Santeon example suggests, coordination works best for hospitals that serve different geographic markets (and, therefore, are not in direct competition with one another). The advantage of the model is that it can deliver benefits with a relatively limited investment. Participating institutions can start small, focus on a specific service or pathway where practitioners are enthusiastic about working together and learning from one another, and then, as the initiative makes progress, expand to more pathways or a broader scope of services.

That said, there is a limit to what coordination can achieve in the absence of strong common leadership and shared budgets. The coordination model is not particularly effective when the goal is to achieve scale in order to invest in new technology or create common, integrated clinical pathways. And change tends to happen more slowly with coordination than with the other models.

Integration

In contrast to loose coordination, integration involves the consolidation of nonclinical back-office functions such as IT or the combination of clinical services to create a more fully integrated care delivery system. It typically involves more standardization and the managed reduction of variations in clinical practice.

Integration allows institutions to benefit from economies of scale. It can also be a way to expand a hospital’s clinical offerings. For instance, building scale and volume in a given clinical specialty can allow institutions to invest in new subspecialties within a given clinical domain. Finally, integration can also extend the scope of care delivery by creating clinical pathways that integrate the full range of treatments and services provided to populations of patients suffering from the same disease.

An example of a health system that has achieved high degrees of integration is Intermountain Healthcare, a not-for-profit health system headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah, and serving the health care needs of people across the Intermountain West region of the US, primarily in Utah, southern Idaho, and southern Nevada.

With annual revenue of about $7.7 billion and nearly 40,000 caregivers, the system comprises a network of 24 hospitals (including one virtual hospital) and 215 clinics, as well as telehealth services provided across a six-state area. It also has its own medical group made up of some 2,400 physicians and advanced practitioners, as well as a network of about 3,800 affiliated physicians. Finally, the system has its own proprietary health insurance plan with approximately 900,000 members, which is roughly 40% of the system’s patients—a higher percentage than any other provider insurance plan in the US, with the exception of Kaiser Permanente.

Intermountain is widely recognized as a leader in clinical-quality improvement and efficient health care delivery and is exceptionally good at the longitudinal management of patients across sites of care. For example, the system’s primary care model, known as Reimagined Primary Care, creates incentives for primary care physicians to spend more time with high-risk patients so that caregivers can prevent potential health problems and minimize expensive hospitalizations. The program has led to a 60% reduction in Medicare Advantage admissions, 25% fewer commercial insurance admissions, a 20% drop in per-member per-month costs, as well as higher patient and physician satisfaction.

Intermountain also forges strong links with its affiliated physicians—for example, by providing technology and value-added services to integrate payment and reimbursement. The system also has its own purchasing organization in which supply chain experts work closely with clinicians to influence physicians’ choice of medical supplies, allowing Intermountain to win volume-based discounts on pricing. And in 2018, Intermountain joined with seven other hospital systems including the Mayo Clinic and HCA Healthcare to launch Civica Rx, a nonprofit generic-drug manufacturer, in order to ensure that participants have a consistent supply of low-cost generic drugs.

Intermountain has been so successful at using integration to improve the value it delivers to patients that, in 2019, the system launched a new company to help providers, payers, and other stakeholders transition to value-based care. Known as Castell, the company provides analytics software and other digital technology to address virtual care, the patient experience, and the social determinants of health; help customers manage affiliated networks; and offer access to Intermountain’s continuous-improvement initiatives. Castell positions Intermountain as an orchestrator of integration for other, less mature health systems.

As the Intermountain example suggests, integration can be an effective way to support the delivery of distributed care and population health management through better coordination with secondary (and even primary) care. Hospitals can gain the benefits of integration, however, without necessarily merging into a single health system with common ownership. For back-office integration, institutions can achieve scale economies simply through shared governance. Clinical-services integration, by contrast, typically requires merging operational leadership at the tertiary level, although not necessarily at the secondary level.

Change tends to happen more slowly with coordination than with the other models.

Reconfiguration

Finally, reconfiguration involves a thorough reorganization of care delivery. It is the most elaborate form of consolidation and the approach most likely to unlock major benefits. But it is also the most difficult, organizationally, to pull off.

Reconfiguration is the approach most likely to unlock major benefits—but also the most difficult, organizationally, to pull off.

Typically, reconfiguration involves the rationalization of specialist centers across an integrated network of hospitals. Consider the recent experience of Italy’s Humanitas hospitals. Humanitas is a private hospital group consisting of nine specialized hospitals and affiliated clinics that serve nearly a million people in three regions of Italy. The group consistently ranks among the top three care providers in the nation.

In 2010, Humanitas embarked on a six-year reconfiguration initiative to streamline its clinical pathways and rationalize its services. The group reorganized its 54 separate clinical units into seven cross-cutting institutes focused on specific disease areas. Clinicians are typically hired by a single hospital or clinic in the network, although they have dual accountability to both hospital managers and the relevant disease area institute. Patients move between hospitals if they require specialized care that is not provided at their local hospital. Support functions such as HR, IT, and procurement are centralized, as are allied health sciences such as pharmacy.

As part of the transformation, Humanitas established its own academic medical center known as Humanitas University, which includes a research hospital, medical school, and life sciences research center. The university functions as a central hub that sets operational and health outcomes targets for the entire system. Individual hospitals have considerable autonomy to operate within the parameters set by the system. But the center has the authority to step in and take control when an individual site consistently fails to meet the group’s targets.

In a sense, the transformation effort at Humanitas traveled through each of the three versions described here—from coordination to integration to reconfiguration. Humanitas spent the early years of the initiative building consensus among clinicians in the various disease areas where the reorganization would improve care delivery. The model was piloted in the group’s oncology service (which accounted for the largest share of revenue, about 30%, at the hospitals). The knowledge gained from this initial pilot was then applied to the other clinical areas. By emphasizing clinician engagement and allowing clinicians to set the pace of change, the change process minimized “us versus them” dynamics, ensured that KPIs were tangible and relevant to the clinical community, defined new roles and career paths within the redesigned clinical pathways, and helped to align incentives across the organization.

The reorganization into disease-based centers of excellence has allowed Humanitas to optimize capacity across the entire care pathway (as opposed to individual operational units), which has helped improve its bottom line. It has also put the managerial focus on what types of care are most likely to improve health outcomes for patients, thus eliminating unnecessary care and leading to major improvements in clinical outcomes.

For example, Humanitas began systematically tracking a broad spectrum of health outcomes and process metrics two years before the Italian Ministry of Health mandated such tracking. And the group’s growing reputation for delivering best-in-class health outcomes led to a major increase in demand for the group’s services. The end result: Humanitas has achieved double-digit growth in an Italian health system where spending has been essentially flat.

As the Humanitas example suggests, the reconfiguration model is especially appropriate for tertiary services in a geographically contiguous area. The approach enhances the benefits of scale by reorganizing clinical pathways, in particular through the consolidation of low-volume or high-complexity services. It also provides an opportunity to shift to new distributed models of care with centers of excellence supporting distributed networks of providers. But the scale of the change generally requires significant investment in infrastructure, a relenteless focus on change management, and strong community and political support. In some developing countries where the health system is relatively underdeveloped, it may be possible to leapfrog directly to the reconfiguration model. But in health systems with existing legacy infrastructure, this model is more likely to be the end-point of a gradual evolution.

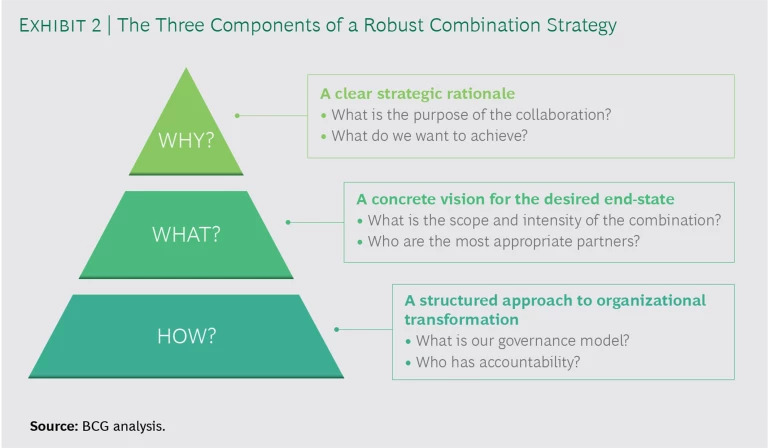

Developing a Robust Combination Strategy

As hospital leaders work to develop effective strategies of combination, they need to focus their efforts on addressing three critical questions. (See Exhibit 2.)

Why Should We Pursue Combination?

Begin by developing a clear strategic rationale for combination and deciding what you are trying to accomplish. Is it to achieve economies of scale in terms of cost or quality? To assemble a critical mass of resources to invest in biomedical innovation or digital technology? To create new career pathways that will appeal to your top clinicians? In addition to identifying the likely financial benefits, it’s also important to show the likely positive impact on patients’ health outcomes and overall population health.

What Is Our Vision of the Desired End-State?

Next, develop a concrete vision for the desired organization end-state. Determine what form of combination—coordination, integration, or reconfiguration—makes the most sense given your strategic goals. Also, identify some intermediate steps along the way to the final end-state that will help the organization achieve the necessary buy-in or build the required capabilities. Finally, on the basis of your objectives and preferred approach, select the most appropriate governance model and the most likely partners.

How Do We Get from Here to There?

Once you have identified the “why” and the “what” of combination, focus on the “how” by developing a structured approach to organizational change. Don’t get trapped into moving at the pace of your slowest partner organization. Avoid this by judiciously choosing some pilot projects that achieve quick wins and demonstrate the value of combination to all participants. Another critical step early in the effort is to establish top-down governance with clarity about who has accountability for key strategic and operational decisions.

Finally, in communications with key clinical constituencies in the participating organizations, emphasize the benefit to patients in terms of improved health outcomes or greater convenience, rather than focusing exclusively on benefits to the organization’s bottom line. For example, by implementing health outcomes tracking, institutions can use this data not only to improve the benefits delivered to patients but to communicate to the organization about the progress being made toward the long-term vision.

In the future, most institutions will be part of larger hospital groups, alliances, or networked systems. That’s why hospital leaders need to get their combination strategy right today.