This article is part of a series of publications offering practical guidance on business ecosystems. Other installments address more key questions: “ Do You Need a Business Ecosystem? ” “ Why Do Most Business Ecosystems Fail? ” “ How Do You Manage a Business Ecosystem? ” “ How Do You Succeed as a Business Ecosystem Contributor? ”

If designing a traditional business model is like planning and building a house, designing an ecosystem is more like developing a whole residential district: more complex, more players to coordinate, more layers of interaction and unintended emergent outcomes.

What makes ecosystem design distinctive is that it requires a true system perspective. It is not sufficient to design the value creation and delivery model; the design must also explicitly consider value distribution among ecosystem members. This is further complicated by the limited hierarchical control in an ecosystem and the need to convince partners to participate, which poses specific governance challenges. And ecosystems exhibit strategic challenges not found in other governance models, such as how to solve the chicken-or-egg problem of creating a critical mass of partners and customers during launch and how to build a scalable and defendable model.

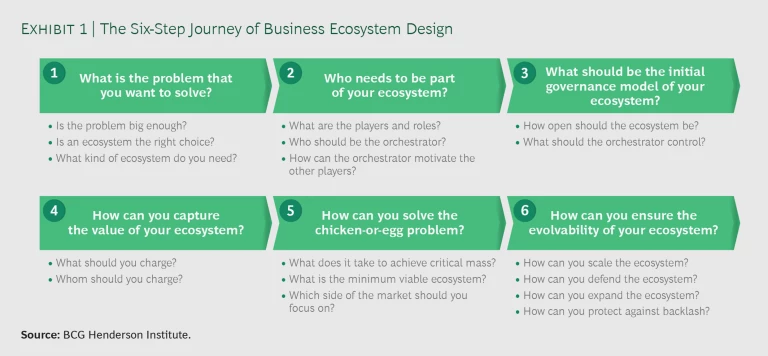

Moreover, business ecosystems, similar to residential districts, cannot be entirely planned and designed—they also emerge. This adaptability is actually one of their major strengths. However, there are some key design choices you need to get right in order to increase the odds of success. These design choices are not independent; they must be consistent with one another and offer a coherent overall configuration. Based on an analysis of more than 100 successful and failed ecosystems across sectors and geographic markets, we find that the ecosystem design challenge can be addressed by working through six sequential questions (see Exhibit 1):

- What is the problem that you want to solve?

- Who needs to be part of your ecosystem?

- What should be the initial governance model of your ecosystem?

- How can you capture the value of your ecosystem?

- How can you solve the chicken-or-egg problem during launch?

- How can you ensure evolvability and the long-term viability of your ecosystem?

Step 1: What is the problem that you want to solve?

Is the problem big enough?

Before you can start designing your ecosystem, you must make sure that the problem that the ecosystem is supposed to solve is clearly defined and large enough to justify the high upfront investment and to convince the right partners to participate. The value proposition for a new ecosystem can come from removing an existing friction (anything that dissuades customers from buying a product or service, such as high cost, delay, poor quality, imperfect functionality, unpredictability, and misunderstanding or lack of trust) or from addressing an unmet or new customer need.

The value potential from addressing an unmet need is difficult to predict but potentially very rewarding, because there is initially no offering to compete with. Who would have guessed 20 years ago that posting selfies, photos of your food, and cat videos is such a deep human need that multibillion-dollar businesses like Instagram and YouTube could be built on them? By contrast, removing an existing friction is more predictable. The ecosystem value proposition is a function of the size of the friction, the share of the friction that can be eliminated by the ecosystem solution, and the willingness of customers to pay for it.

Who would have guessed 20 years ago that posting selfies, photos of your food, and cat videos is such a deep human need that multibillion-dollar businesses like Instagram and YouTube could be built on them?

Take, for example, Better Place, a startup founded in 2007 to build an innovative ecosystem-based solution to power electric vehicles (EVs). Its breakthrough idea was to separate car and battery. In this model, the driver purchases a car without a battery, while Better Place owns the battery and charges a mileage-based monthly fee for leasing, charging, and exchanging it. In this way, Better Place could solve several fundamental problems of existing EV offerings: Because Better Place owned the battery, the EV could be offered at a competitive price, and the risk of obsolescence and low resale value due to advances in battery technology was eliminated.

Because Better Place built not only charging infrastructure but also switch stations that could exchange batteries in a matter of minutes, the problem of limited driving range was also addressed. And finally, Better Place also solved the problem of electric grid capacity, because as the orchestrator of the EV ecosystem it could balance the power demand from cars with grid capacity. Better Place was thus able to remove substantial frictions and offer an enormous benefit to the world. However, as we will see, the ecosystem failed because of other weaknesses in its design.

The specific value proposition of a business ecosystem is context dependent. For example, frictions in traditional retail were much higher in China than in the US, because China had no significant retail or payments infrastructure and it was difficult for consumers to get access to many products they were looking for. This explains in large part the success of transaction ecosystems like Taobao and Tmall, which largely removed these frictions.

In a similar vein, B2C ecosystems are typically easier to establish than B2B ecosystems, because many existing B2C relations suffer from relatively high transaction costs, while B2B offerings are more likely to be characterized by mature companies with optimized professional relationships. In the early 2000s, there was huge excitement about the value potential of B2B marketplaces in the US, with estimated online exchange potential of more than $5 trillion by 2005. In fact, by that year, almost all B2B marketplaces in the US had disappeared. The bubble collapsed mainly because the problems that could be solved through these marketplaces were just not important or big enough. Again, the situation was different in China, where the lack of infrastructure made it difficult for a business to find partners, a problem that Alibaba largely solved. However, we also believe that advances in sensor technology, cloud computing, and data analytics will make it possible to address new and bigger problems, and IoT-based business models will likely fuel the next wave of B2B ecosystems in the coming decade.

Is an ecosystem the right choice?

The next question that must be answered is whether an ecosystem is the best way to realize the business opportunity. Ecosystems compete with other governance models, such as vertically integrated organizations, hierarchical supply chains, and open-market models. As we discussed in the first article of this series (“ Do You Need a Business Ecosystem? ”), an ecosystem is the preferred model in unpredictable but highly malleable business environments and when high modularity of the offering is combined with a high need for coordination among players.

There are many examples of business opportunities that are not well suited for an ecosystem model. Who wants to fly in an aircraft that was built by a loosely coordinated ecosystem of companies? In this case, the complexity and integrated nature of the design, and the need for utmost attention to safety, favor an integrated model or a hierarchical supply chain. On the other hand, many business opportunities do not require a business ecosystem because they can be realized in an open-market model. For example, if Saeco launches a new automatic espresso machine, the required coffee beans, water, and power supply are generic complements that consumers can purchase in the open market and then combine on their own.

There are many examples of business opportunities that are not well suited for an ecosystem model. Who wants to fly in an aircraft that was built by a loosely coordinated ecosystem of companies?

Sometimes the best governance model is not so obvious—or can change over time. Zappos started as a transaction ecosystem, matching consumers with shoe manufacturers, but found that it could offer a more consistent value proposition by taking full control of the buyers’ experience with a traditional hierarchical supply chain model.

What kind of ecosystem do you need?

Not all business ecosystems are created equal. Some business opportunities are best organized as a solution ecosystem, which creates and delivers a product or service by coordinating various contributors. Others are best set up as a transaction ecosystem, which matches or links participants in a two-sided market through a (digital) platform . And some are best organized as a hybrid, combining elements of a solution and a transaction ecosystem. It is important to be clear about the type of ecosystem, because the types differ not only in their structure but also in their purpose, success factors, and value creation mechanisms.

Step 2: Who needs to be part of your ecosystem?

What are the players and roles?

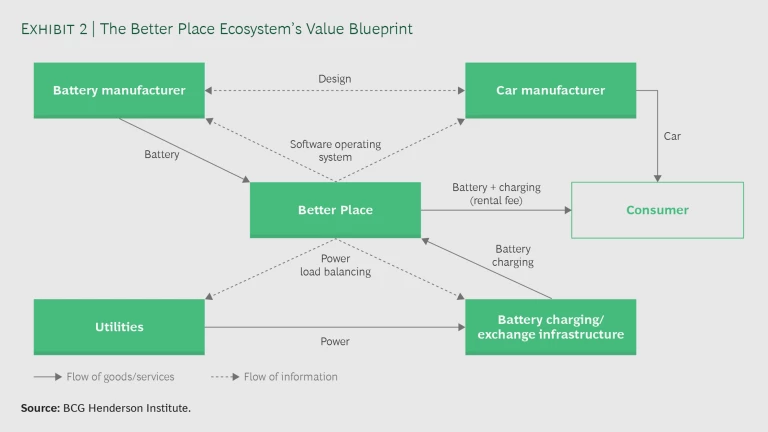

The initial design of a business ecosystem starts with mapping the “value blueprint”: the activities that are required to deliver the value proposition, the links among them, and the responsibilities of the various actors. The value blueprint also specifies the flow of information, goods or services, and money through the ecosystem. (See Exhibit 2.)

The design of an ecosystem should be driven by its core value proposition. The initial value blueprint should incorporate the minimum number of domains (types of participants or market sides) that are needed to provide this core value and expand over time. All examples of hybrid models that we know started either as a transaction ecosystem (Airbnb, Alibaba, LinkedIn) or as a solution ecosystem (Apple iOS, Android) and added further domains and offerings only once they were firmly established.

The value blueprint is the basis for assigning roles to the various players. A solution ecosystem is typically characterized by a core firm that orchestrates the offerings of several complementors, suppliers, and intermediaries (such as Better Place’s ecosystem in Exhibit 2). In transaction ecosystems, the orchestrator role is played by the owner of a central (mostly digital) platform that links producers and their suppliers with consumers.

The different roles have benefits and drawbacks. The orchestrator builds the ecosystem, encourages others to join, defines standards and rules, and acts as arbiter in cases of conflict. The broad scope of the role comes with the bulk of responsibility for ecosystem success and the sustained level of investment that is required to get the ecosystem going. The orchestrator is the residual-claim holder of the ecosystem. While it has a big influence on the distribution of the value created, it must also make sure that all relevant players earn a decent profit. In return, the orchestrator can keep the residual profit, which can be very high (Apple iOS, Microsoft Windows) but also negative for an extended period of time (Uber, Lyft). Orchestrators that fail in their responsibility to secure fair value sharing will sooner or later destroy their ecosystems.

Who should be the orchestrator?

In many business ecosystems, the assignment of the orchestrator role is clear. For example, in most transaction ecosystems the provider of the matching platform is the natural orchestrator, and the roles of producers and consumers are readily assigned. Similarly, some solution ecosystems are built on a technical platform that serves as the basis for orchestration, such as the console of a video game ecosystem or the operating system on a PC or smartphone.

You cannot unilaterally choose to be the orchestrator. You need to be accepted by the other players in the ecosystem.

However, as a new ecosystem emerges, the orchestrator role may be contested. Think of the competing smart-farming ecosystems that are currently being built by equipment manufacturers (John Deere), seed and crop protection providers (Bayer-Monsanto), and technology players (Alphabet). And who should be the orchestrator of an effective ecosystem for electronic health records: health insurers, providers, IT companies, or the government?

It is important to understand that you cannot unilaterally choose to be the orchestrator. You need to be accepted by the other players in the ecosystem. In this regard, there are four requirements for a successful orchestrator of a business ecosystem. First, the orchestrator needs to be considered an essential member of the ecosystem and control resources needed for its viability, such as a strong brand, customer access, or key skills. Second, the orchestrator should have a central position in the ecosystem network, with strong interdependencies with many other players and a resulting high need and ability for effective coordination. Third, the orchestrator should be perceived as a fair (or even neutral) partner by the other members, not as a competitive threat. And finally, the best candidate is likely to be the player with the highest net benefits from the ecosystem and thus a correspondingly high ability to shoulder the large upfront investments.

Most companies seem to strive for the orchestrator role because they fear being commoditized, losing direct access to customers, or being exploited by another orchestrator. However, being a supplier or complementor in a business ecosystem can be a very attractive role. Arguably, the biggest winners of the Californian gold rush in the mid-19th century were the suppliers of pots, pans, and Levi jeans. Similarly, suppliers and complementors can benefit from lower investment requirements and the opportunity to join the most attractive of several ecosystems. Or they can hedge their bets and participate in more than one ecosystem. In particular, if they provide important components that represent a bottleneck for the ecosystem, they can secure a substantial share of the overall profits.

An example of a highly successful complementor is Adyen, a Dutch payments company enabling global platforms to support all key payment methods around the world. At the time of writing, the company had a market cap of more than €25 billion, had more than doubled its stock price since its IPO in June 2018, and reported revenue growth of 41% in the first half of 2019 at an EBITDA margin of 57%. Arithmetic dictates that only a small minority of firms can be orchestrators. We are convinced that many incumbents would be well advised to put their strategic focus on finding attractive complementor or supplier roles.

How can the orchestrator motivate the other players?

Ecosystem orchestrators face the additional challenge of motivating the required partners to commit and contribute to the ecosystem. Ron Adner identified two important risks for the feasibility of an emerging ecosystem: co-innovation risk and adoption risk.

Co-innovation risk stems from the fact that developing a new or substantially improved value proposition is typically associated with high risks for the individual required innovations. In the case of a business ecosystem, these individual risks multiply because of the interdependence of the different components. The probability of technical success of an ecosystem solution equals the mathematical product of the probability of success of all required components, which can be very small if just one factor is small.

This co-innovation risk is particularly relevant for solution ecosystems, where the failure of one critical component is sufficient for the entire ecosystem to fail. For example, in early 2000, Nokia and Sony Ericsson started a race to bring to market the first 3G mobile phone capable of video streaming. Nokia had forecast that by 2002 more than 300 million mobile handsets would be connected to the internet. The actual number was 3 million; 300 million was reached in 2008, six years later. Nokia became a victim of co-innovation risk: While Nokia was fast to the market and could sell its first 3G handset in 2002, before Ericsson, other actors in the ecosystem still had to develop solutions to fully enable video streaming, such as formatting software to fit TV images on small phones, router innovations allowing mobile phone operators to know which customer signed up for which plan, and digital rights management to ensure copyright protection for content owners. Before these innovations were established, 3G video streaming could not be viable, rendering the device largely useless.

Assessing co-innovation risk is important to evaluate the overall probability of success of the ecosystem, but also to identify the bottleneck components that need most attention and support. Intel understood this challenge when the company designed its ecosystem and created the Intel Architecture Lab to drive architectural progress on the PC system and to stimulate and facilitate innovation on complementary products.

Even if co-innovation risk seems limited, there is another challenge related to the value blueprint: adoption risk. Because of the high interdependencies in a business ecosystem, all contributors to the overall solution need to be ready, willing, and able to participate and invest in the ecosystem. A single instance of rejection is enough to break the entire adoption chain. For example, Better Place finally failed in spite of a compelling value proposition because it could not secure the participation of one important group of partners in its ecosystem, the car manufacturers. It got Renault on board by guaranteeing volume and placing an order of 100,000 cars, four years before it had a single customer. But Renault ultimately was Better Place’s only car manufacturing partner.

How can you evaluate critical partners’ incentives to participate? Partners are more likely to commit if they score high on the following criteria:

- High relative profit increase from participation

- High competitive risk from non-participation

- Limited investments required for participation

- Limited risk from participation

- Existing capabilities to build on

If some critical players show a high adoption risk, you may need to reflect this in your ecosystem design with incentives for participation. Incentives need not be only monetary; they can, for instance, also include access to customers or data. Ron Adner mentions digital cinema projectors as an example. The value proposition for replacing analog films and projectors by digital counterparts was generally compelling: higher resolution, better protection from piracy, and significant savings in the value chain. The cost of producing a conventional film was $2,000 to $3,000 per print, costing $7.5 million for a release shown on 3,000 screens. Regardless of these advantages, adoption risk proved to be very high for cinemas because the investment costs were prohibitive relative to the benefits. Despite efficiency gains, higher quality for consumers, and more flexibility regarding the offering, cinemas saw no need to adopt digital projectors on a large scale. Only once the film studios established a financing scheme in which they shouldered the initial outlay for the projector, and studios shared the benefits by paying a virtual print fee per digital film screened (covering ~80% of the cinema investment costs), were the incentives for adoption high enough to establish the new technology on a broader scale.

Step 3: What should be the initial governance model of your ecosystem?

How open should the ecosystem be?

Ecosystem governance is an important design choice because it creates an indirect form of control appropriate to the complexity and dynamism of an ecosystem. It establishes the standards, rules, and processes that define an ecosystem’s formal or informal constitution. Governance needs to balance two requirements for ecosystem success: value creation (rules of collaboration to co-create value as an ecosystem) and value sharing (rules and processes for splitting the value among ecosystem players).

The single biggest governance question for an emerging ecosystem is its degree of openness. Questions in three areas must be answered:

- Access. Which individual partners will be allowed to participate in the ecosystem? Which requirements do they have to fulfill in order to get access to the platform and its resources?

- Participation. To what extent are ecosystem partners invited to shape the ecosystem? What is the scope, detail, and strictness of the rules governing this? Who decides how the value created is distributed among partners?

- Commitment. What level of ecosystem-specific investments and co-specialization is required? Is exclusivity demanded or are partners allowed to multihome in competing ecosystems?

In practice, we can observe successful ecosystems with very different levels of openness, from rather restrictive (Nespresso) to managed (video games) to very open (Airbnb). For example, the Chinese company Haier chooses a rather open approach toward access to its emerging “internet of food” ecosystem, which tries to integrate players from the appliance, food, health care, home furniture, logistics, and even entertainment industries to create a comprehensive customer solution from buying to cooking, eating, storing, and cleaning. As Zhang Ruimin, chairman of the Haier group, put it, “We want to build an energetic rainforest rather than a structured walled garden.”

On the other hand, Sony experienced the peril of an open governance model when introducing its e-reader. Alarmed by piracy in the music industry, publishers were extremely concerned to protect their rights around books. Sony did not manage to establish a governance model to address this concern. Therefore, Amazon could conquer the e-book market as a late entrant by establishing the Kindle as a very closed platform that loaded content only from Amazon and precluded users from transferring books to any other device or to a printer.

In some sectors, ecosystems compete on their degree of openness. For example, Android broke the dominance of Apple iOS as a mobile operating system with a very open governance model, while Facebook overcame the weaknesses of Myspace’s open model by being initially very selective about who it allowed to join and establishing the double-opt-in “friending” feature.

How can you find the right level of openness for your ecosystem? The decision must optimize the tradeoff between the advantages of a more open setup and of a more closed setup. Open ecosystems can benefit from faster growth, particularly during launch. They enable greater diversity of participants and variety of offerings and encourage decentralized innovation. Open ecosystems tend to use the market to guide their development; partners join and leave and adjust their offers as customer demand and technologies evolve.

How can you find the right level of openness for your ecosystem? The decision must optimize the tradeoff between the advantages of a more open setup and of a more closed setup.

On the other hand, open ecosystems are difficult to control and are thus best suited for products and services with limited downside and relatively low cost of failure. In case of high failure costs, and a corresponding need to limit the downside, a closed ecosystem may be the better solution. It allows for a more deliberate design of the ecosystem and for closer control of partners and of the quality of the offering. Moreover, a more closed ecosystem helps the orchestrator capture value by, for example, charging for access.

The right level of openness for a given ecosystem will depend on the relative importance of the individual factors, such as growth versus quality, decentralized versus coordinated innovation, and speed versus consistency of co-evolution. Competition with other existing or emerging ecosystems in the same sector can also play a role, because a new ecosystem needs to find a differentiated positioning, such as the degree of openness.

We have seen many ecosystems start with a rather closed governance model in order to establish high quality and open up later. For example, the Q&A platform Quora started as an invite-only ecosystem that targeted prominent technology entrepreneurs. By building this dense and exclusive network of experts, Quora was able to develop an inventory of high-quality content that then made it easy to attract a broader audience when the platform later opened up. However, there are also examples of ecosystems that start as open to gain traction and become more closed later, such as the knowledge ecosystems investigated by Järvi and her colleagues.

We have seen many ecosystems start with a rather closed governance model in order to establish high quality and open up later.

What should the orchestrator control?

As an orchestrator, you face an additional design question: What do you want to do yourself and what do you want to encourage complementors to do? A starting point may be your own assets and capabilities. However, as Hannah and Eisenhardt observe, “Perhaps in complex strategic settings like ecosystems, strategy is more consequential than initial capabilities.”

Good ecosystem strategy may be to identify and occupy potential innovation or capacity bottlenecks that can become an important source of value. Successful orchestrators claim important system control points that allow them to capture their fair share of value. For example, Nest decided to engage in alarm and monitoring itself because these are essential functionalities for controlling the home. Apple pre-installs Apple Maps on the iPhone in an attempt to oust Google Maps. And Google uses its Google Play store to control the otherwise very open Android ecosystem.

There are, of course, many other initial governance questions. For example, when designing a transaction ecosystem, the platform orchestrator must decide whether the matching of producers and consumers should be done by algorithm (Uber) or by users (Facebook); whether pricing should be based on rules and algorithms (LendingClub) or on offer and negotiation (eBay); and whether curation should be done by platform editors (Wikipedia), user feedback (Airbnb), or algorithms (Google Search). These decisions depend on the specific context and get at the heart of the ecosystem’s operating model, value creation mechanism, and differentiation.

We will address the question of ecosystem governance in more detail in a future article in this series.

Step 4: How can you capture the value of your ecosystem?

What should you charge?

When the basic setup of the business ecosystem is defined, the next big design step is to find a way to translate the benefits that the ecosystem creates for its customers into value for its participants. Monetization is one of the biggest challenges of the ecosystem orchestrator, which must balance three competing objectives: maximizing the size of the total pie; enabling all important domains (groups of participants) of the ecosystem to earn enough profit to ensure their ongoing participation; capturing its own fair share of the value.

To achieve this, the orchestrator must design not only the value proposition for the customer but also the value-sharing model, by defining the value proposition for each group of relevant stakeholders. At the same time, the orchestrator must make sure to own critical control points, such as access to the customer, products with many interfaces, or critical services.

In solution ecosystems, value capture is typically rather straightforward because the solution that the ecosystem creates can be sold as a product or service. The orchestrator can in addition capture value from complementary products or services through access fees, licensing fees, revenue shares, or sales of value-added products or services to complementors. For example, Apple takes 30% of revenues for all apps sold through its App Store, and Nespresso takes a license fee from machine makers such as Krups, Breville, and De’Longhi.

Transaction ecosystems offer many more options for capturing value. The orchestrator can charge for access, for example, with a general access fee to the platform, an enhanced access fee for producers for better targeted messages or interactions with particularly valuable users, premium access fees for consumers, or enhanced curation fees for users who are willing to pay for guaranteed quality. The orchestrator can also charge for usage in the form of a transaction fee, either a fixed fee per transaction or a percentage of the transaction price. In addition, the orchestrator can charge for supplementary products or services (such as invoicing, payments, insurance), or it can monetize the ecosystem indirectly through advertising revenues.

Whom should you charge?

The second critical question of value capture is whom to charge. Again, the orchestrator has a number of choices, such as charging all participants, charging only one side of the market while subsidizing the other side, or charging most users the full price while subsidizing selected marquee users or particularly price-sensitive users.

Our analysis showed that mispricing on one side of the platform is a key reason for failure, in particular in the launch phase (see the next section). For example, Table8, a platform for last-minute reservations in sold-out restaurants, failed because it charged the wrong side of the market. The company learned the hard way that few guests were willing to pay $20 or more for a reservation in a high-profile restaurant. Competitors like OpenTable that charged restaurants for their reservation service turned out to be more successful. Similarly, eBay had to learn that its established model of charging users to list products and services did not work in China because the practice discouraged sellers to set up online shops, whereas Taobao offered a cost-free system that was financed solely by advertisements.

How can you find the right monetization strategy for a given business ecosystem? In general, monetization should be designed so that it does not stifle the growth of the ecosystem but instead encourages and incentivizes participation and thus fosters network effects. This can be achieved, for example, by charging for transactions rather than access, subsidizing the side of the market that is less willing to participate, or offering rebates for increased usage and rewards for inviting others to join the network. A good starting point is to identify the participants with the highest willingness to pay and charge them according to the net excess value they derive from the ecosystem.

In general, monetization should be designed so that it does not stifle the growth of the ecosystem but instead encourages and incentivizes participation and thus fosters network effects.

Moreover, monetization should be used to overcome bottlenecks in the ecosystem and to encourage innovation by, for example, subsidizing bottleneck players and offering better terms for new products. Of course, the pricing strategy of an ecosystem can change over time. Many platforms initially subsidize one or both sides of the market to overcome the chicken-or-egg problem during launch. However, most of them realize that it is difficult to transition from free to fee and that they need to offer new, additional value to justify the change.

Step 5: How can you solve the chicken-or-egg problem during launch?

What does it take to achieve critical mass?

Many ecosystems fail during the launch phase because they cannot solve the chicken-or-egg problem of sufficient participation of both buyers and sellers/producers. They do not achieve the critical mass to secure network or data flywheel effects, whereby scale begets further scale. An analysis of 57 ecosystems in 11 sectors across geographic markets by the BCG Henderson Institute found that half of the investigated ecosystems never took off.

When we looked deeper into the successes and failures, we noticed many misunderstandings regarding ecosystem launch. First, despite the paramount importance of network effects in many business ecosystems, first-mover advantages are often overestimated. It is not about being the first in the market, but being first with a complete solution. The Apple iPod was not the first digital music player, but it was the first to offer a comprehensive solution by combining the hardware product with the iTunes music management software.

Second, the size of the network should be measured not by vanity metrics, such as the number of members, but by the number of interactions or transactions, which is how business ecosystems create value. Most network effects are “local” (not only in a geographical sense), so network density may be a more important driver of value for users than network size.

Third, it is not only about the quantity of participants but about the right participants (such as the most attractive restaurants for an online booking platform like OpenTable) in the right proportions (such as a balanced number of drivers and riders for a ride-hailing ecosystem like Uber). Identity and culture are important success factors for a business ecosystem, and it is difficult to change them once they are established. Ecosystem growth is thus strongly path dependent, and the selection of early members and the sequence of attracting members can have a big impact. You can even experience negative network effects from attracting “bad” users, as Chatroulette, the random video chat platform, experienced with its “naked-hairy-men problem.”

What is the minimum viable ecosystem?

An important consideration to increase the odds of a successful launch is to start with a minimum viable ecosystem (MVE), a term coined by Ron Adner.

To quickly get to critical mass and build a dense network, many successful ecosystems we observed initially constrained themselves by geography.

To quickly get to critical mass and build a dense network, many successful ecosystems we observed initially constrained themselves by geography. For example, Airbnb first focused on New York, and even as the company started its international expansion in 2011, it focused on creating critical mass in just a few markets. Similarly, OpenTable conquered one city at a time, following the rule of thumb that once 50 to 100 concentrated restaurants in a city subscribed, enough consumers would use the platform.

On the other hand, many failed ecosystems expanded too quickly. For example, Better Place may have been able to overcome the chicken-or-egg problem if it had focused on its two core markets, Israel and Denmark, where it achieved early success. However, the company moved too quickly to establish toeholds and run pilots in a wide range of new locations and ran out of money before it could secure the critical level of sales volumes to attract and retain partners—most important, automakers.

Other failed ecosystems completely ignored the MVE concept and launched an offering that was too broad rather than focusing on the core transaction. For example, Club Nexus, an early social network created in 2001, allowed students to chat, send emails, post events, buy and sell goods, and post images and articles. The complexity of features made the platform difficult to use and weakened the strength of its network. Facebook learned from this failure and started with only very simple profiles and allowed users to view only other people who went to the same school.

Which side of the market should you focus on?

In solution ecosystems, the main challenges are typically on the complementor side: convincing partners to commit to and invest in an unproven business opportunity. It helps if the orchestrator credibly demonstrates its own commitment through a large upfront investment in the ecosystem, as Microsoft did when it entered the video game console market in committing to sell the Xbox at a low price to convince game developers that there would be demand for their products. In addition, Microsoft subsidized some marquee developers to join the ecosystem. The orchestrator can make it easier to join by providing free or subsidized tools and services for complementors. Some orchestrators even sign conditional contracts with complementors and/or customers obliging them to join the ecosystem if it gets enough members of the other group to participate. If this does not work, the orchestrator can still develop or buy some of the required complements itself to kick-start the ecosystem. For example, Apple launched the iPhone with a number of applications that it developed in-house, including a web browser, mail, contacts, calendar, photos, videos, and iTunes.

Transaction ecosystems have an even larger number of levers at their disposal to kick-start the platform. Sometimes they can build on the existing infrastructure or customer base of a linear business model, as Amazon did when it opened its established e-commerce system to external producers and launched Amazon Marketplace. Or they can piggyback on an existing transaction ecosystem, like PayPal did on eBay’s online auction platform.

If this is not possible, the critical question is which side of the market to focus on initially in order to build critical mass. Most ecosystem orchestrators that we analyzed focused first on building supply, and they used various levers to do so. Some seeded and subsidized one side of the market. For example, Uber initially guaranteed drivers $40 per hour as long as they kept the app running and maintained an acceptance rate of 70%. Some attracted supply by providing free or subsidized tools and services (Airbnb), subsidizing marquee producers to join the platform (Twitter), or creating an initial offering by acting as a producer themselves (Quora, Reddit). An interesting strategy can be to create standalone value for one side first. For example, OpenTable started by building a suite of software tools for restaurants to replace their manual booking process, which created the technical preconditions and a loyal base of suppliers for their online booking platform.

The critical question is which side of the market to focus on initially in order to build critical mass.

Supply-constrained ecosystems should not shy away from more traditional levers. Most successful food delivery platforms, for instance, started by hiring a field sales force that simply walked into restaurants during their downtime and talked to owners to convince them to join their ecosystem. Many ride-hailing platforms used referrals to incentivize existing suppliers to bring new suppliers to the platform.

Some transaction ecosystems are not supply-constrained and should focus on growing the demand side. For example, TaskRabbit quickly had thousands of people on the waitlist to provide services, while it turned out to be more difficult to build demand. The company deliberately constrained supply by charging an application fee and processing background checks in order to increase the quality of the offering and thus attract demand.

Other ecosystems follow a zigzag strategy to bring on both sides of the market at once. For example, Alibaba worked hard on getting Chinese suppliers and foreign buyers on board simultaneously when it first launched. YouTube also pushed participation by both sides simultaneously and alternated between strategies to get more people to upload and more people to view. The Japanese firm Recruit, which builds ecosystems to reinvigorate mature service markets, deploys what it calls its Ribbon Model to alternate between building supply and building demand.

And finally, some successful platforms use context-dependent creative and even devious tricks to overcome the chicken-or-egg problem. Twitter achieved its breakthrough by traditional push marketing with a big-bang event at the 2007 South by Southwest (SXSW) tech festival. Airbnb, instead of building supply from scratch, used readily available information on property owners who wanted to rent out their properties from Craigslist, a popular online classified website. And Uber launched Operation SLOG (Supplying Long-term Operations Growth) to aggressively attract drivers from rival ride-hailing service Lyft.

We conclude that successfully launching a business ecosystem is a big challenge that requires more than a strong initial design. It takes persistence, deep pockets, and sometimes the willingness to follow unusual and creative approaches that may not be financially sustainable, in order to kick-start the ecosystem. However, if the ecosystem is to be viable in the long run, it also needs to be designed for evolvability.

Step 6: How can you ensure evolvability and the long-term viability of your ecosystem?

How can you scale the ecosystem?

In contrast to most traditional business models, many business ecosystems have the potential not only for supply-side economies of scale but also for demand-side economies of scale and the resulting positive feedback loops. In particular, demand-side scale effects enable many ecosystems to grow quickly and exhibit winner-takes-all or at least winner-takes-most characteristics (at least for some time). However, some ecosystems have only limited demand- and supply-side economies of scale. And many ecosystems have failed because they did not solve the scalability challenge.

Demand-side economies of scale make networks more attractive to users as more users participate in the ecosystem. They can be based on direct (same-side) or indirect (cross-side) network effects. More traditional market-building instruments, such as a strong brand, can reinforce these network effects. Demand-side economies of scale are larger for ecosystems with global business models (travel booking platforms) than for multi-local ecosystems (food delivery platforms), where the network effects are limited to small local clusters. Moreover, an ecosystem may experience negative network effects and declining quality from growing the network, for example, if it becomes increasingly difficult to find the best match in a growing transaction ecosystem. Such negative network effects can be limited through effective (and scalable) curation using data, algorithms, and social feedback mechanisms.

Supply-side economies of scale can be based on falling fixed or variable costs. They are particularly strong in many digital ecosystems, which are frequently characterized by asset-light business models (Airbnb achieved a dominant position in the hospitality market without owning a single hotel), low-to-zero marginal cost (no significant effort of serving an additional customer on the Amazon Marketplace), and increasing returns on data (more effective matching of riders and drivers on a growing ride-hailing platform). Supply-side scale effects can be limited by sticky costs, for example, if competition between ecosystems requires ongoing high marketing and recruiting investments (food delivery platforms) or if a fast rate of technological innovation requires ongoing high research and development expenses (ride-hailing). Moreover, the rising cost of complexity and quality control may counterbalance positive scale effects as the network grows.

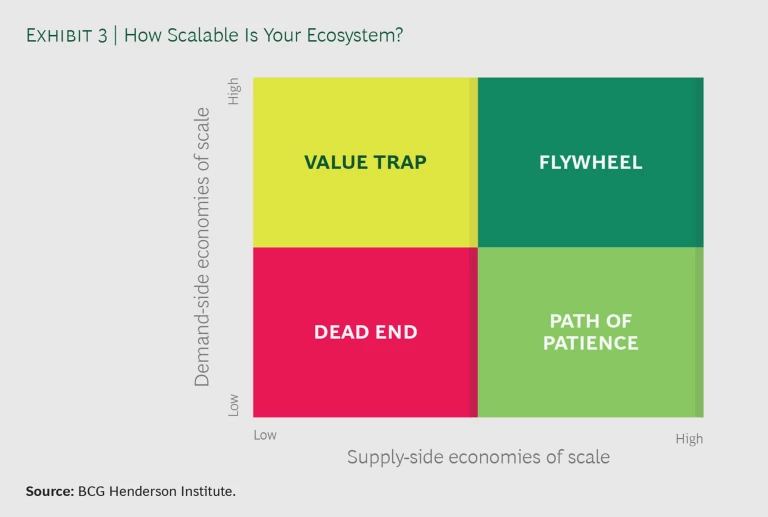

We suggest a simple matrix to analyze the scalability position of your ecosystem. (See Exhibit 3.)

Airbnb is an example of an ecosystem with both substantial demand-side economies of scale (indirect network effects) as well as supply-side economies of scale (from spreading the high fixed-cost for technology and marketing). We characterize this model as a flywheel, with winner-takes-all-or-most characteristics.

Some ecosystems have supply-side economies of scale but only limited demand-side economies of scale, such as additive manufacturing and many other solution ecosystems with small network effects. They need to follow a path of patience when it comes to growth, but they also have a good chance of achieving a profitable and defendable position.

More critical are ecosystem models that have high demand-side economies of scale but limited supply-side scale effects. We call them value traps. Ride-hailing platforms may be an example. The model clearly has substantial positive indirect network effects that support explosive growth, but it lacks substantial scale benefits on the supply side, mainly because of the high recruiting and retention cost for drivers. Such businesses can struggle to become sustainable.

And then there are examples of ecosystem plays that have neither substantial supply- nor demand-side economies of scale. We call them dead ends. An example is the original Yahoo internet portal and search engine, which started as an employee-edited hierarchical database that classified webpages using a tree structure of categories. This model worked well for some time, but as the internet grew exponentially, it became apparent that it was not scalable, and Yahoo was overtaken by Google with its automatic and easily scaling page-rank algorithm.

It is important to understand the scalability position of your emerging ecosystem and to adapt your ecosystem design and ecosystem strategy accordingly. However, scalability is only the first step toward long-term viability. To thrive in the long run, your ecosystem also needs to be defendable.

How can you defend the ecosystem?

Ecosystems have some built-in defensibility advantages, and many exhibit natural winner-takes-all-or-most characteristics. Once they have achieved a dominant market position, strong barriers to entry result from the network effects and scale advantages on costs and data mentioned above. Moreover, ecosystems compete at the system, not at the product, level, which gives them a deeper type of competitive advantage that is more difficult to copy and attack than just a superior product or service.

Our analysis of successful and failed ecosystems showed that many ecosystems found it easier to achieve scale than to sustain it.

However, our analysis of successful and failed ecosystems showed that many ecosystems found it easier to achieve scale than to sustain it. Defending a strong position as an ecosystem is challenging because an attack can target either the demand or the supply side of the market. We identified four main mechanisms of attack that ecosystems need to be aware of.

First, multihoming happens when suppliers or consumers participate in multiple competing ecosystems at the same time, or easily switch between ecosystems. Restaurants may find it attractive to offer their dishes on multiple food-delivery platforms, for instance, and consumers use different hotel-booking platforms to chase the best offering. Multihoming is a particular risk for an ecosystem if switching costs are low. For example, because credit cards tend to have low annual fees, many people carry multiple cards in their wallet. By contrast, only few people can afford to carry both an Android and Apple phone, so they tend to choose one model and stay with it for at least a couple of years.

Second, disintermediation happens when partners from two sides of a transaction ecosystem bypass the matching platform and connect directly. For example, Homejoy, an online platform that connected customers with home service providers, including house cleaners and handymen, suffered from disintermediation as customers who were satisfied with the service of a cleaner did not return to the platform but hired the person directly. Homejoy closed down in 2015.

Third, differentiation and attack from niches happens when a subset of users has distinctive needs or tastes that can support a separate ecosystem and take away market share from the dominant player. For example, Upwork, the leading marketplace for freelance labor, found it difficult to establish a defendable dominant position (and earn a decent return) because of market fragmentation and competition from hundreds of niche players that focus on specific industries, job types, or locations.

And finally, ecosystem carryover happens when a successful business ecosystem expands into a neighboring domain. It is an important route for ecosystem growth and expansion, as we will discuss in the next section, but also a significant threat for established ecosystems. A special case of ecosystem carryover is nested ecosystems. For example, we could imagine that ride-hailing platforms at some point may come under pressure from broader mobility-as-a-service ecosystems that include multimodal transport solutions, which may in turn be attacked by even broader smart-city ecosystems.

Digital technologies, while offering new ways of exploiting network effects and supply-side economies of scale, also make it more difficult to defend an established position. Digital business models have much lower entry barriers than traditional brick-and-mortar businesses. It is so easy to create a digital platform today that you do not even need to program your own software but can build it from components available on cloud-services platforms. Digital network effects as a barrier to entry are much weaker than the physical network effects of a railway or telephone network. Moreover, they can quickly be reversed once a network starts losing users and gets into a downward spiral, as once-dominant platforms like Second Life and BlackBerry have painfully experienced. And finally, the high rate of innovation and technological disruption in this field means that established ecosystems will always be challenged by new players with a better concept and a more exciting offering. Think of how Myspace killed Friendster, only to be subsequently killed by Facebook.

BCG Henderson Institute Newsletter: Insights that are shaping business thinking.

If you want to design your business ecosystem for evolvability and long-term viability, you need to build in some characteristics that make it easier to defend. How can you evaluate how well your ecosystem is prepared? Here are four essential questions:

- How strong are network effects in your ecosystem?

- To what extent can your ecosystem benefit from supply-side economies of scale?

- How high are multihoming and switching costs on the demand and supply side?

- To what extent is your ecosystem protected from specialized niche competition?

The application of the four defensibility tests to ride-hailing platforms such as Uber, Lyft, and Didi uncovers the fundamental challenges of their business models. On the positive side, there is only limited threat from niche specialization in ride-hailing, and the platforms can clearly benefit from substantial indirect network effects. However, these effects are only local and difficult to transfer to new cities. More importantly, ride-hailing suffers from multihoming and low switching costs for riders, who have a high incentive to use multiple ride-hailing services, as well as drivers, who can easily switch between platforms or even serve multiple platforms at the same time. As indicated above, the resulting high recruiting and retention costs for drivers lead to limited supply-side economies of scale, further reducing barriers to entry.

By contrast, video games score better in the defensibility test. They exhibit moderate, but global, indirect network effects, benefit from substantial supply-side economies of scale (low marginal cost of selling an existing game), and experience limited threat from niche specialization. However, the industry suffers from multihoming of game developers, who have high incentives to work for multiple console producers, as well as of players, who are further encouraged by subsidized console prices. As a result, Microsoft, Nintendo, and Sony have formed a rather stable oligopoly for an extended period of time, but market shares have varied from console generation to generation, depending on the newly introduced games and hardware features.

What can you do as an orchestrator to improve the defensibility of your ecosystem? Of course, you can try to increase barriers to entry. For example, you can reduce the incentive to multihome by building proprietary standards that suppliers must follow or by creating loyalty programs for users. You can also implement a rather strict governance that requires suppliers to commit exclusively to your ecosystem. However, this will also limit their incentive to join your ecosystem in the first place.

The most effective defense, however, is to ensure that you offer the best available product or platform and the best overall ecosystem solution. Having only a superior product or platform is no longer sufficient in an ecosystem world, where competition happens at the system level. In many ways, the BlackBerry was superior to the iPhone—in terms of data security, keypad, and battery life—but Apple offered the far-better overall solution with its ecosystem of app developers.

The most effective defense is to ensure that you offer the best available product or platform and the best overall ecosystem solution.

At the same time, you must not neglect your core product. In 2004, Microsoft’s Internet Explorer captured close to 95% market share and was widely considered to have won the browser war. However, with no serious competitor left, Microsoft underinvested in the further development of the browser and its underlying ecosystem. Inferior product execution and product innovation from 2004 to 2015 allowed Firefox and Chrome to enter and eventually dominate the market.

In the end, the only way to defend your leading position as an ecosystem is to be the technology and innovation leader in your industry, to encourage all partners in the ecosystem to relentlessly innovate, and to continuously adapt and reinvent your ecosystem, before others do.

How can you expand the ecosystem?

The exact route of expansion of a business ecosystem cannot and should not be planned in advance. A key benefit of ecosystems is their responsiveness to changing consumer needs and technological opportunities. It is thus important for an ecosystem orchestrator to be open to the creative potential of consumers and complementors, and to build flexibility and adaptability into the model.

An ideal ecosystem architecture uses a modular setup with clearly defined interfaces, such as APIs in digital ecosystems. They define how ecosystem members connect to the overall system and should provide the element of stability of the ecosystem. When complementors can rely on the stability of interfaces, they can flexibly innovate and add new functionalities to the system. Even major technological changes in the core product or platform can be easily accommodated, as long as the interfaces remain stable. In this way, Microsoft managed to defend Windows as the dominating PC operating system over three decades, in spite of substantially changing technologies and customer preferences.

Three pathways for expansion should be considered in ecosystem design. First, expansion can happen by adding new products or services to an existing ecosystem. For example, LinkedIn started as a social network, allowing users to connect with other professionals through simple profiles. Over time, it added further services, such as a marketplace for online recruiting, advanced messaging features, and a content publishing platform. Second, an existing ecosystem can be used to expand into adjacent markets. For example, Uber started as a ride-hailing service and successively expanded into other mobility-related services, such as food delivery, e-bikes and scooters, and courier services (which shut down in 2018). And finally, ecosystem carryover is a strategy that leverages the success of one ecosystem to create advantage in constructing a new one. For example, Apple used its strong position in the music player ecosystem to conquer the smartphone ecosystem by positioning the iPhone as the next-generation iPod. In this way, the iPhone started with a built-in, loyal customer base, which gave Apple a decisive competitive advantage in this emerging market.

As these examples indicate, many different assets can serve as a basis for ecosystem expansion. It could be existing relationships to customers and/or complementors that can be transferred to new applications, as in the case of the iPhone. It could be idle capacity, as in the case of Amazon, which used server capacity from its retail operations as a starting point for building Amazon Web Services. It could be technology, as in the case of Alphabet, which used its Google navigation technology to build the Waymo ecosystem for self-driving vehicles. And it could be data, as in the case of Alibaba, which used information from transactions on its Taobao marketplace to build the Ant Financial ecosystem. Whatever the critical assets for future expansion will be, ecosystem orchestrators need to ensure in their ecosystem design that they control them.

How can you protect against backlash?

A number of large platform-based ecosystems have recently experienced a substantial backlash from consumers and regulators. For example, marketplaces such as Amazon and eBay were criticized for not collecting sales taxes to gain a competitive advantage. Uber and Airbnb were accused of escaping regulation in the transportation and hospitality sector in order to avoid costly requirements for safety, insurance, hygiene, and workers’ rights that apply to taxis and hotels. And Facebook was harshly criticized for its data privacy policies and for false and misleading stories disseminated on the platform.

It is true that many ecosystem models have successfully exploited missing regulation for new technologies or gaps in existing regulation. However, as ecosystems begin to dominate larger parts of our economy, social and regulatory scrutiny will increase, and members of an ecosystem must accept, anticipate, and address their growing responsibility. To this end, it is important to design your ecosystem not only for legal compliance but also for long-term social acceptance, and to make it robust in the face of shifts in public values and perceptions. For example, the high energy intensity of many digital business models has recently been increasingly criticized, and designing an ecosystem with a favorable climate footprint may soon become an important competitive advantage.

There are also increasing concerns that dominant ecosystems may become too big to control and could abuse their market power. Existing antitrust legislation in most countries is not well suited to regulate business ecosystems. To avoid a regulatory backlash, ecosystem orchestrators should anticipate such concerns, continuously challenge their ecosystem design, and work with regulators to ensure broad social acceptance. More important, they should preempt regulation by self-regulating and not abusing their central role in the ecosystem and their ecosystem’s role in the economy. In the long run, a business ecosystem will prosper only if it continues to create tangible value for its customers and ensures fair value distribution among all contributors to the ecosystem.

Designing a business ecosystem is a major undertaking. The six steps and underlying interdependent design choices we present here can help. A business ecosystem that is well-designed in this way has the potential to create entire new industries or substantially shape and transform existing industries.

At the same time, it is important to accept that business ecosystems cannot be entirely planned and designed—they also emerge. Ecosystem design must ensure that the basics are in place and strategic blunders are avoided, but it must also leave room for creativity, serendipitous discoveries, and emerging customer needs. Ecosystems that are successful in the long run need to be adaptable and be ready to modify their designs in anticipation of shifts in markets, technologies, regulations, and public sentiment. They must also be ready to embrace the serendipity of unintended and unforeseen opportunities.