World leaders are committing unprecedented funds to recovery packages. Their choices will shape our economies and societies for decades, and determine whether we breathe clean air, create a sustainable low-carbon future and possibly even survive as a species.

—Ban Ki-Moon, former UN Secretary General

The public sector’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been unparalleled. To date, governments have pumped more than $11 trillion in direct stimulus funding into their economies—and these programs are likely just the opening salvo. Such spending dwarfs the $600 billion per year that governments, multilateral agencies, and the private sector around the world allocate to climate investments, according to the Climate Policy Initiative’s estimate. Given the scale of current stimulus funding, governments have a critical opportunity to design their stimulus programs in a way that accelerates progress toward net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Governments looking to seize this opportunity must manage seemingly difficult tradeoffs. As job losses mount in many countries, governments feel pressure to preserve established industries—many of which are fossil fuel intensive. At the same time, some governments and businesses are pushing for a rollback of environmental protections, including climate-related regulations, under the guise of stimulating economic recovery.

But climate progress and a strong rebound from the COVID-19 crisis are not mutually exclusive . A well-designed recovery program can not only bolster GDP, create jobs, and lower emissions in the near term, but also transform the country for leadership in the green economy over the long term. To ensure that they deliver on this opportunity, governments should tailor their plans to their country’s specific circumstances. Through our work, we have identified seven country archetypes that reflect a nation’s industrial mix, and the capabilities and skills of its workforce. The best approach for each archetype varies significantly.

Although approaches may vary, the urgency to act does not. According to the most recent UN Environment Programme Emissions Gap Report, global temperatures are on track to rise by 3.2°C by the end of the century. In order to limit global temperature increases to 1.5°C degrees, the target set five years ago at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 21) in the Paris Agreement, the international community must slash global annual emissions by 35 gigatons (Gt) annually in this decade. Fortunately, the economic case for climate action is growing stronger: a 2019 International Monetary Fund analysis found that the domestic environmental benefits of a $50 carbon tax exceed the costs for just about every G20 country.

All governments should engineer their stimulus programs to advance a green, resilient recovery and to support their climate commitments ahead of next year’s COP 26 meeting in Glasgow. Such action will drive progress in addressing the planet’s greatest threat and ensure their countries will thrive in a low-carbon future.

The Potential of a Green Recovery

Given the magnitude of the challenge, government stimulus programs offer a critical opportunity to accelerate progress on mitigating climate change. New research published in Nature Climate Change indicates that channelling 1.2% more of global GDP into green energy while shifting investment away from fossil fuels could reduce emissions by up to half this decade.

Evidence is mounting that, if done well, green recovery programs can yield robust economic benefits. New research from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the IMF outlines a sustainable recovery plan for the next three years. The plan would require an annual investment of about $1 trillion for three years—a relatively small share of stimulus spending to date—and could boost global GDP by 3.5%, creating the equivalent of about 9 million jobs per year over that period. At the same time, those investments would help position countries to compete in emerging green industries.

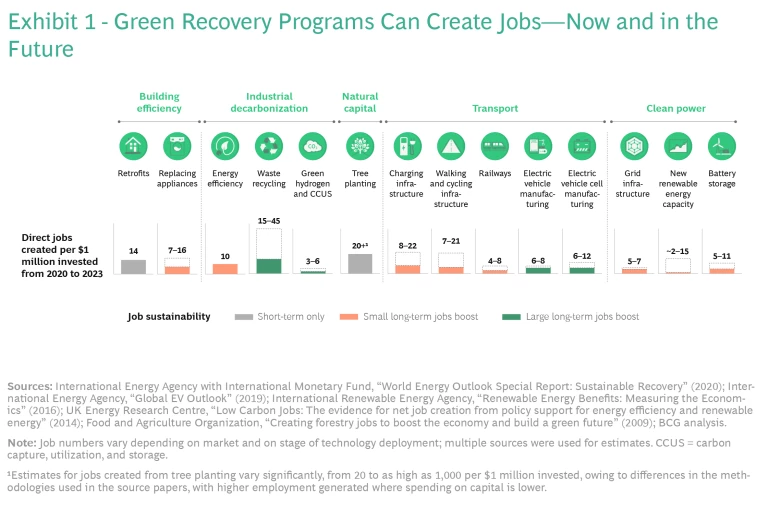

As countries consider how to design green recovery plans, they need to understand how various plan components differ in job creation potential and in duration of impact.

Assessing the Wide Range of Benefits. Payoffs from green recovery efforts fall into four main areas:

- Direct Benefits. These include direct jobs and economic activity resulting from the construction of green projects such as retrofitting buildings for greater energy efficiency. Green recovery efforts also extend to jobs created in the supply chain and in adjacent sectors, such as heat pump and insulation manufacturing.

- Indirect Benefits. The ripple effects of green stimulus spending can be quite large. For instance, incentivizing energy efficiency retrofitting—in forms such as the recent introduction of renovation vouchers in the UK, or the low-interest-rate financing offered by Germany’s KfW state bank—boosts economic activity in two ways. First, it increases the demand for people working as retrofitters, who will then spend their wages elsewhere in the economy. Second, it reduces household energy bills, freeing up funds that those households can spend on other goods.

- Noneconomic Benefits. Some positive spillover effects are not reflected in near-term employment or GDP numbers. Carbon emissions, for example, have real-world costs, including property damage from increased flooding and negative impacts on human health. In addition, increased energy efficiency can have significant positive social effects, including reducing fuel poverty and other forms of economic hardship.

- Future Benefits. As traditional industries such as internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle manufacturing and fossil-fuel power decline, a green recovery plan can ensure that countries are competitive in fast-developing new markets. At the same time, the expansion of new green sectors can boost the economies of struggling regions. The rapid growth of the offshore wind industry in Britain’s Humberside region, for instance, has provided a major economic boost to the area.

Aiming for Near-Term and Long-Term Impact. Governments have the opportunity to design policies that provide both a near-term boost for recovery and jobs and a long-term economic transformation.

Near-term responses typically involve interventions that offer a strong boost to jobs and GDP in the short run but vary in the duration of their impact. Tree-planting schemes , for example, deliver immediate direct job benefits, although these typically dissipate once the planting is complete. In capital-scarce countries with significant available labor, such schemes can create between 500 and 1,000 jobs per $1 million invested.

Governments can combine short-term policies with other initiatives—such as investments in electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure or grid capacity expansion—that provide a longer-lasting economic boost. Customers benefit from a lower cost of vehicle ownership and reduced power costs, and the nation wins by creating long-lasting jobs. The German government, among others, has already incorporated these approaches into its recovery plan, making a €2.5 billion investment in EV charging infrastructure and providing a €9,000 subsidy per vehicle to encourage adoption.

Solar photovoltaic (PV) energy and offshore and onshore wind energy technologies also offer opportunities for sustained job creation and GDP growth. These technologies are relatively mature and are more labor intensive per unit of power generated than is new gas or coal power technology. Research conducted by the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts indicates that every $1 million of government stimulus funding redirected from fossil fuel power to green power creates an additional five jobs.

Over the long term, governments can invest in transformative new technologies such as green hydrogen and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). Although these burgeoning industries may take time to develop and scale, they can ultimately create significant numbers of jobs in research and development and infrastructure construction.

A combination of near-term and long-term initiatives can have a significant positive impact. The IEA/IMF plan mentioned above, for example, contains initiatives that create both short-term temporary jobs and long-term permanent employment gains. (See Exhibit 1.)

One Size Does Not Fit All

The opportunity to build a future economy that captures new value pools in low-carbon technologies is not uniform. The size of the opportunity depends on an array of factors, including a country’s existing manufacturing base and its workforce capabilities. At the same time, the feasibility of implementing a green recovery may be limited. In particular, countries that depend heavily on fossil fuels and have weak balance sheets will have less incentive to move aggressively.

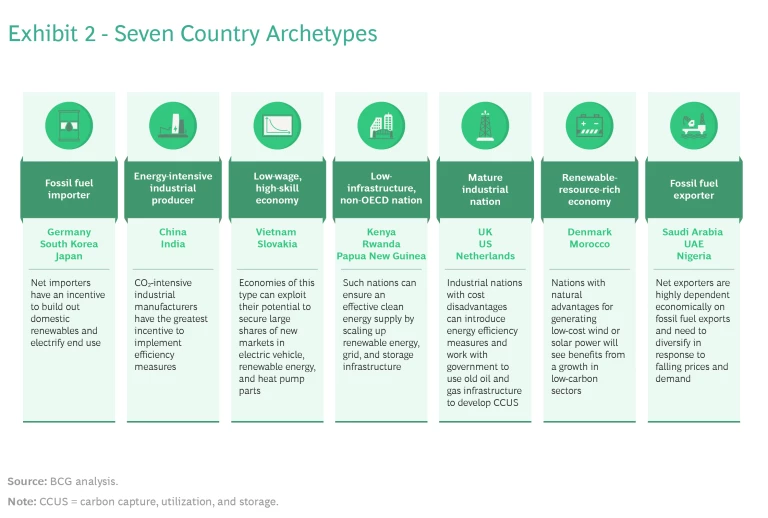

Seven Archetypes. Seven clusters of countries have emerged in response to the opportunity presented by a green recovery program. (See Exhibit 2.)

The archetypes for these clusters are as follows:

- Fossil Fuel Importer. This category includes countries such as Germany, South Korea, and India. For such countries, accelerating the shift to clean power and to electrifying mobility and heating will strengthen national security, improve the balance of trade, reduce the cost of power to consumers, and potentially promote development of a robust domestic manufacturing industry.

- Energy-Intensive Industrial Producer. This type of country will find significant potential in efficiency measures to reduce its cost base. For countries with a prominent export trade, such as China, adopting such measures can help protect their operations from carbon border adjustment taxes that major markets such as the EU are currently considering.

- Low-Wage, High-Skill Economy. Nations with low manufacturing costs, including some in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, can capture sizable shares of new markets for low-carbon products. Areas of opportunity might include assembling or making parts for EVs, renewable energy infrastructure, or heat pumps. EV models developed by Vietnamese startup VinFast, for example, will use locally produced components, if possible, and serve both a rapidly growing domestic market and the international export market.

- Low-Infrastructure, Non-OECD Nation. Countries in this category can increase the share of their energy that comes from renewable sources, lower their cost of energy, and prepare for new industrial growth by scaling grid and storage capacity. Increasing grid access in rural communities, in particular—including via microgrids—can promote more efficient and cost-effective domestic use.

- Mature Industrial Nation. Countries such as the US, the UK, the Netherlands, and Norway are finding their international competitiveness challenged by lower-cost, higher-carbon rivals. Securing their heavy industry by leading in low-carbon products would give them a clear competitive advantage against rival economies. Energy efficiency programs can bring their cost base more closely into line with competitors. More transformative moves toward full decarbonization are another opportunity. For example, mature industrial countries can leverage their highly skilled workforces and concentrated industrial clusters to repurpose decommissioned oil and gas infrastructure into CCUS facilities.

- Renewable-Resource-Rich Economy. Countries that fit this archetype can exploit natural advantages for low-cost wind and solar power generation and position themselves as leaders in the green manufacture of energy-intensive products, including hydrogen, synthetic fuels, steel, and chemicals. Countries in this category include Denmark (which has the potential to generate large amounts of wind power), and Morocco (which has significant potential to generate solar power).

- Fossil Fuel Exporter. The declining price of oil is likely to have a severe negative impact on major producing nations. No OPEC member nation could balance its 2019 budget when oil prices were below $50 per barrel—and that represents an optimistic projection for 2020 prices. Furthermore, the economic crisis caused by COVID-19 and the ongoing movement toward renewables may mean that the world has already passed its peak demand for fossil fuels. Major oil producers, including countries in the Middle East and Africa, would do well to diversify and future-proof their economies by investing in low-carbon opportunities, including green hydrogen.

In pushing to position their economies in emerging green sectors, however, governments must move quickly. Delaying could enable other nations to establish an advantage that countries slower off the mark cannot overcome. (See the sidebar.)

The Battle for the EV Market

Jobs in the ICE industry are under threat in several traditional major markets. Pre-COVID-19 competition from low-labor-cost economies strained margins and led to offshored production. The pandemic has compounded the problem by lowering demand for vehicles. Meanwhile, the ongoing growth of automation continues to reduce the number of workers required.

Several studies have shown that companies can maintain or even expand the number of jobs during the transition from ICE production lines to EV manufacturing. Europe alone could see the creation of 200,000 jobs across the full EV value chain by 2030, according to a study by the European Association of Electrical Contractors, creating net new employment even as the ICE industry declines. However, such projections assume that countries will move quickly to capture a high share of exports and retain production across the value chain.

Doing so will not be easy. China has already taken an early lead in EV parts manufacturing. Other governments should therefore direct green stimulus support to help traditional OEMs accelerate development of their in-house EV skills. For governments in mature industrial nations that may be wavering, the risk could be sizable. Volkswagen is poised to start producing some EV models in Slovakia, a country with high skill levels and low wages, where recent state investment in gigafactories could help the nation double down on its competitive advantage.

Understanding Feasibility. Although every country has an opportunity to drive a green recovery, the incentive to move aggressively is hardly equal from one nation to another. Two factors help shape the degree to which an ambitious green recovery program is feasible:

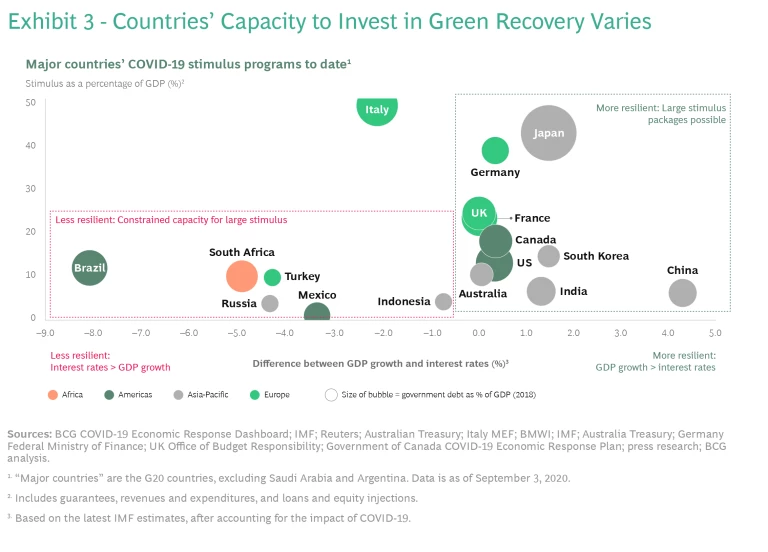

- Fiscal Position. Countries that maintain strong balance sheets (low debt and high fiscal reserves) and GDP growth that outstrips interest rates have the economic bandwidth to invest in a green recovery. Many of these countries have already introduced ambitious stimulus programs, and they possess the fiscal flexibility to do even more. Countries with weaker balance sheets and a higher cost of borrowing have less room to maneuver. For these countries, finding additional support through overseas development assistance, multilateral development banks, and multilateral institutions such as the G7 and G20 will be vital. (See Exhibit 3.)

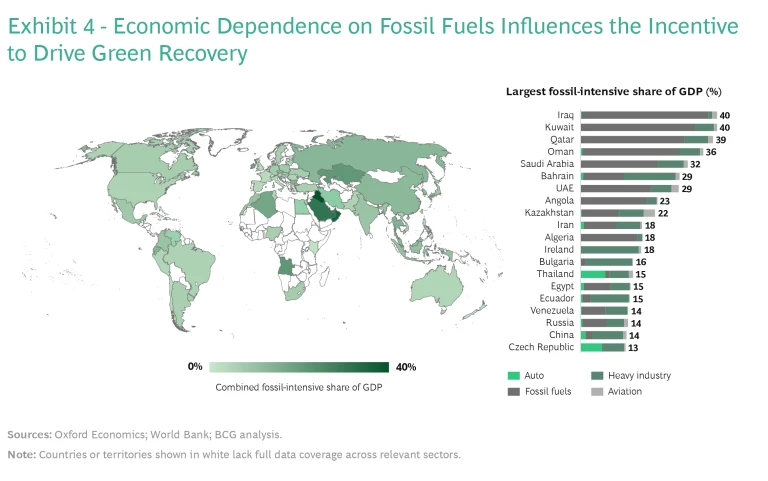

- Dependence on Fossil-Fuel-Related Sectors. In countries where fossil-fuel-intensive industries such as industrial goods production, ICE vehicle manufacturing, and nonrenewable power generation account for a large share of jobs and GDP, governments are likely to be reluctant to aggressively push a green recovery plan. (See Exhibit 4.) In some countries, the concentration of these jobs in economically challenged areas, where skills are limited and the opportunity for new industries is low, compounds the issue. These countries may face an additional challenge because workers with skills in fossil-fuel-related industries dominate their labor force, making it more difficult to find the skilled workers needed in expanding green sectors.

A Deep Dive in Two Countries. To understand how nations’ green recovery plans may vary, consider the cases of Denmark and Vietnam. These countries align with different archetypes, and both the opportunities for and the feasibility of a green recovery differ. Nevertheless, both countries can chart their own successful paths toward a green recovery.

A renewable-resource-rich nation situated between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, Denmark has emerged as a global leader in the offshore wind industry, with major domestic players such as Vestas and Ørsted carving out strong positions in equipment manufacturing and power production, respectively.

A green recovery for Denmark could double down on this technical advantage, expanding the export markets for its domestically manufactured wind-turbine technologies. Denmark might also take advantage of its natural ability to produce zero emissions power to lead the way in producing low-carbon products in energy-intensive sectors. With a large European market on its doorstep, Denmark could play a prominent role in the manufacture of green hydrogen and green steel. And because making green steel and green hydrogen often entails constructing new manufacturing sites that are near renewable power sources, government-aided investment in building these sites in Denmark could be extremely effective.

Vietnam, meanwhile, has a very different opportunity. A nation with a low-cost, high-skill economy, it has mounted a strong response to COVID-19, and its economy is likely to be one of quickest in Asia to rebound from the pandemic. Despite the country’s historically weak fiscal position, this rapid rebound should strengthen it considerably; indeed, some analysts think that it may avoid recession entirely.

Leveraging this economic strength could enable Vietnam to position itself as a leader in Southeast Asia, capable of exporting to other regional leaders and beyond. Currently dependent for much of its energy on large amounts of imported coal, the country could take this opportunity to focus on previous investments in the solar sector to create domestic jobs and bolster growth. This strategy could help Vietnam improve its national security and its balance of trade. At the same time, the growth of domestic EV player VinFast has developed capabilities in parts manufacture and assembly. Using this advantage to export low-cost parts to major global OEMs as they switch to EVs could secure Vietnam’s position as a global sector leader.

Policymakers in Denmark and Vietnam, as in all countries, face unique pressures and have their own particular preferences. The key for each country will be to tailor the plan to its own context, focusing on areas where it has a competitive advantage.

Implementing a Green Recovery

All nations must contend with certain implementation hurdles if they are to deliver a successful green recovery. Previous attempts at green stimulus have revealed several pitfalls. The response to the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 in many cases included support for a green recovery. The ten largest programs directed a combined total of $263 billion toward green initiatives, roughly 16% of the total spent. Together with domestic green growth initiatives, such as the UK’s Green Deal, these efforts have helped define best practices that nations should adopt to improve their odds of success:

- Define success and monitor execution. Governments should define what success in a green recovery program will look like, setting clear targets and performance indicators, and they should monitor implementation to ensure that it delivers on the potential. Uncoordinated disbursement of funds without clear accountability for results can lead to subpar results and wasted resources. An independent, unbiased organization is often best positioned to monitor implementation of the program. In the UK a quasi-independent agency, the Committee on Climate Change, scrutinizes the government’s progress on climate action. By monitoring progress and recommending interventions in areas where the policy is falling short, such entities can ensure that green recovery policies deliver the intended environmental and economic outcomes.

- Build wide-ranging political support. Stimulus programs are most likely to be effective when they enjoy support from across the political spectrum and the universe of nonpolitical stakeholders, including government, opposition parties, business leaders, and regulatory bodies. Political dissension contributed to the weak implementation of Australia’s 2008 Green Stimulus, which saw just 35% of the earmarked funds deployed by 2014.

- Design the right incentives. Governments must design policies carefully to ensure that a program realizes its full potential impact. Low-interest-rate financing on green products or targeted subsidies, for example, can help drive changes in consumer behavior and maximize a policy’s chances of success. Much as stimulus programs in the period from 2008 to 2009 helped make renewables cost competitive with fossil fuels, the current round of government spending could help push new green technology up the experience curve.

- Ensure an equitable transition. Planners must design programs in a way that ensures a fair distribution of the benefits and costs of transition. Governments should ensure, for example, that areas such as Teesside in the UK or the Appalachian region in the US, which rely heavily on fossil-fuel-based manufacturing, receive appropriate support during the shift to a green economy. Some governments have already taken action to address the issue. The EU has created a €40 billion transition fund to help some fossil-fuel-dependent regions develop new low-carbon

industries.1 1 Source: Euractiv, “EU boosts ‘just transition fund’, pledging €40 billion to exit fossil fuels” (May 27, 2020), accessible here. At the same time, governments can take steps to minimize job losses. In the oil and gas sector, for example, government can encourage workers to leverage their existing skills on green projects such as the decommissioning of unused infrastructure in the near term while providing training in new fields such as green hydrogen manufacturing over the longterm.2 2 Source: Atlantic Council, “Public sector investment opportunities for a green stimulus in oil and gas” (May 30, 2020), accessible here. - Ensure consistency with overall government policy. Governments should ensure that their overall government policies align with and complement any green recovery program. After all, green recovery efforts are unlikely to lead to sustained emission reductions if they are not supported by broad policies such as cross-sector carbon taxation. At the same time, governments may need to implement measures such as border adjustments to ensure a level playing field for domestic companies and international competitors. Such measures can strengthen the competitiveness of manufacturers that adopt green approaches, thereby ultimately saving domestic jobs.

- Support with regulatory measures. Governments that build the right regulatory foundation—including product standards, public procurement rules, and minimum efficiency standards for household and industrial energy uses—can spur rapid growth of the market for green products. Using regulatory standards to overcome implementation problems can be crucial. In cases where a tenant pays the energy bill but their landlord must bear the cost of retrofitting the property, for example, setting a minimum energy efficiency standard can exert pressure on an otherwise reluctant landlord to make the right retrofitting investments.

A Unique Opportunity

The climate challenge today is urgent and demands global, collective action. The massive stimulus programs being adopted offer a unique opportunity to drive real progress.

A few countries—notably France, Germany, and South Korea—are leading the way, with ambitious recovery packages that aim to drive rapid decarbonization while supporting the development of new domestic industries and long-term competitive advantage. Such initiatives will likely expand in some cases and be replicated elsewhere in coming months. After all, sizable investments are essential to post-pandemic recovery. In 2008, the IMF recommended that countries spend about 2% of their GDP to revive their economies in the face of the financial crisis, and the scale of today’s crisis exceeds the difficulties of that period. It’s hardly surprising that the German recovery package, for example, represents 3% of the nation’s GDP.

Spending on this scale can move the needle on climate change in ways that have eluded society to date. It can help countries meet the climate goals set in the Paris Agreement and position them to seize new opportunities in green technologies. In a best-case scenario, governments will respond to the pandemic-driven postponement of COP 26 by coordinating and aligning their green recovery plans to fuel their own transition to a low-carbon economy while increasing the support they provide to countries that have limited financial resources to make a similar shift.

The potential reward of such action is enormous. Well-designed, well-executed green recovery plans can bend the curve downward on emissions and push the economic growth curve upward, helping secure a more prosperous, secure, and resilient future.

The authors thank Sam Sherburn for his research and analysis assistance in the development of this article.