Remember the Macarena? The song shot to the top of 15 global music charts in 1996 and was certified platinum in seven countries. It was also a one-hit wonder. The band that created it, Los del Rio, did just fine—but they never topped the charts again.

Startups have it relatively easy. They’re only expected to get it right once. If they do, and are acquired by a larger company, it’s a big victory. Larger companies are held to a higher standard. Their valuations depend on the market’s belief that they will be able to innovate successfully into the future. If they don’t, they’re punished by the market.

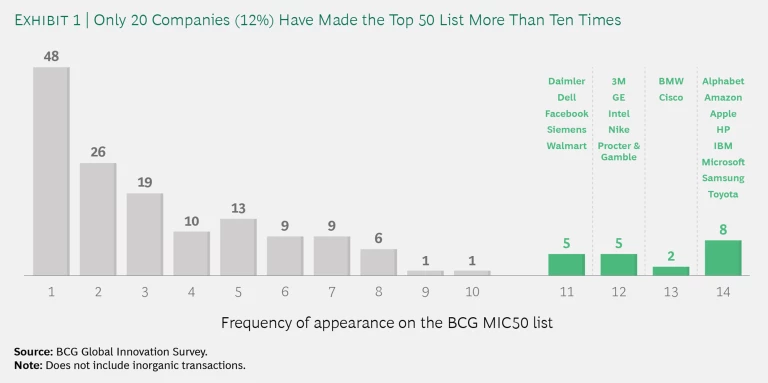

As we mentioned earlier , of the 162 companies that have made BCG’s annual ranking of the 50 most innovative companies since 2005, only eight made the list every year—and only 12% ranked in the top 50 ten or more times. (See Exhibit 1.) Serial innovation is hard. But in the current rapidly shifting customer and competitive environment, it is essential.

The 20 companies that made the list more than ten times come from a diverse set of industries—tech of course but also retail, automotive, industrial goods, and consumer products. (For a look at the 50 companies on the list in 2020 and the evolution of the top 50 over the past 14 years, explore this interactive exhibit .) Elon Musk of Tesla (which has made the list seven times) famously argued that even more important than the product is “the machine that makes the machine.” He has a point. Serial innovators succeed not because of the qualities of any individual offering. Rather, they draw on the strength of their underlying innovation systems, which integrate strategy, ecosystems, portfolio management, governance, development, performance management, and more into one seamless and mutually supportive whole. So what does it take to get it right again and again?

Systematizing Innovation Success

Successful innovation pays. An investment of $100 made in the MSCI World Index in 2005 would have been worth $251 at the end of 2019. The same $100 invested in BCG’s 50 most innovative companies (assuming annual reweighting) would have grown to $327—30% more. Over the 15 years that we have produced this report, the top innovators have outperformed the companies in the MSCI index by more than 1 percentage point a year on sales growth and by 2 percentage points annually on total shareholder return (TSR).

Everyone knows the parable of the blind men and the elephant: each man can feel and describe a part of the animal, but none of them can get a sense of the whole. Elephants are big; innovation systems are complicated and multifaceted. They involve people and teams from multiple functions. They can have lots of moving organizational parts: R&D, ecosystem partners, incubators, accelerators, and corporate venture funds, for example. They include decision-making systems, processes to guide activities, as well as many less tangible factors such as embedded tools, capabilities, and cultural norms of behavior. In recent years, we have examined specific aspects of such systems: how successful innovators source ideas , how they collaborate , how they organize to support innovation , and how they incorporate new technologies into their programs.

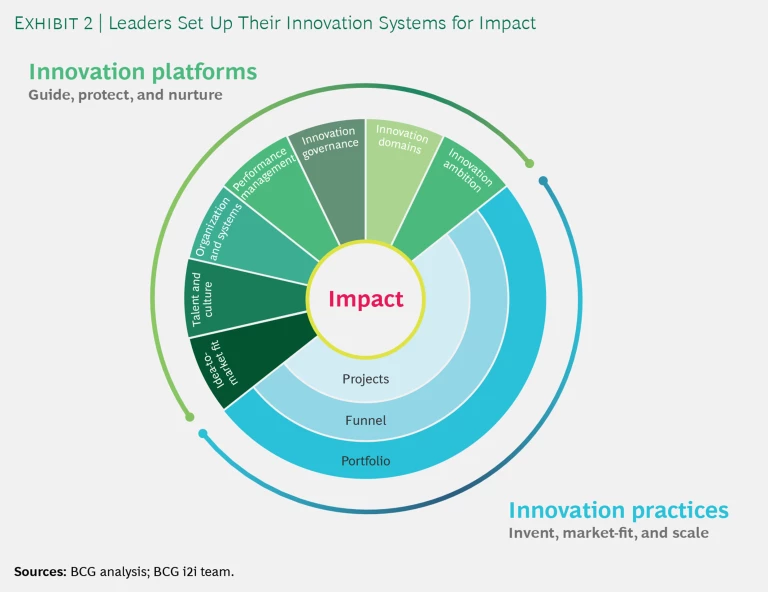

Companies with strong innovation systems do all these things well. But that’s often not enough. Innovation systems are dynamic. They need to be designed and regularly reworked to deliver the desired level of organic profitable growth—but they always need to be seen as a whole. On the basis of our research and experience, we assess innovation systems on ten elements. Seven relate to the innovation platforms and organization that set ambition, define innovation domains, delimit roles, shape portfolios, and measure and reward performance. And three are associated with the actual practice of moving a portfolio of projects to impact. (See Exhibit 2.)

The data from BCG’s innovation benchmarking database shows that companies with better systems achieve an increase of 5 to 20 percentage points in their innovation output (the percentage of sales from products, services, or business models introduced in the past three years).

In our experience, the most successful large innovators take a page from the instruction manual of serial acquirers and systematize the success factors. Serial acquirers integrate the discipline of effective M&A (from target identification and analysis to price setting and negotiation to rigorous post-merger integration) into their management systems. Serial innovators also understand that success depends on all facets of innovation working together toward a common goal of generating a continuing series of new products or services that make an impact where it counts—in the marketplace.

Getting Started

It’s difficult for leaders, even those with 20-20 vision into their organizations, to get their arms around the entire machine and identify what’s working and what isn’t. In most large organizations, the CEO is the only leader who is in a position of authority to drive an innovation system. All other leaders are left with partial or functional mandates. For them to drive change, they need to build exceptional stakeholder orchestration skills in order to cut through silos and build coalitions across the organization.

An effective innovation journey starts with doing the careful work of establishing a common language on innovation, building a fact base for framing the challenge, and getting CEO buy-in. Only then can leaders decide which issues to attack first. What is working well? What are their companies’ most pressing weaknesses? What should they scrutinize first—strategy, governance, process, talent, incentives, culture, or something else?

We have found that a series of pointed questions, each of which focuses on one of the ten essential elements of the company’s innovation system, provide a good way to start. We derived these questions from BCG’s experience working in innovation and validated them against our benchmarking database containing data on the innovation performance and organization of more than 1,000 firms. The questions for innovators in a post-COVID-19 world reflect the typical gaps we see between leading innovators (benchmark companies) and those aiming to join their ranks:

- Innovation Ambition. Do we have a shared innovation purpose? Have we established an aspirational goal aligned with corporate strategy and value creation targets that rallies our best talent to invent better ways to serve customers and society?

- Innovation Domains. Is our innovation strategy grounded in deep customer insight and foresight that help us decide what to do—and not do—and enable us to nimbly adjust to shifting opportunities? Do we focus on a limited number of innovation domains where we have a right to win?

- Innovation Governance. Do we ensure that people and budgets are aligned with our shared innovation priorities—and promptly realigned when priorities shift—even when multiple stakeholders have a voice?

- Performance Management. Do our metrics and incentives reward both predictable, incremental progress and successful step-change innovation? Do we recognize leaders who are not only able to push new ideas but also recognize failures early in the process?

- Organization and Ecosystems. Do we have clear roles for all the disparate elements of our broader innovation ecosystem—for example, R&D units, venturing vehicles, digital units, and external partners—to ensure that we collaborate seamlessly and realize our targets?

- Talent and Culture. Do we have true business builders, and do we allocate our very best talent to our most ambitious innovation challenges?

- Idea-to-Market Fit. What’s the last truly novel idea we developed that solved a “hair on fire” problem for customers?

- Project Management. Do we have a clear view of our unfair advantage relative to our competition, and do we actually manage to wield it?

- Funnel Management. Is our funnel of potentially valuable projects actually funnel-shaped or is it a cylinder? Do we learn from past mistakes?

- Portfolio Management. Do we manage our portfolio strategically, for example, to ensure balance between core and noncore, or among new products, services, and business models? Do we take nonconsensus bets that promise outsize rewards? Have we reassessed and rebalanced our priorities and our portfolio through the COVID-19 lens?

Consider the well-known history of Apple. Ranked #1 in our top 50 list for all but one year since 2005, Apple is a poster child of successful innovation. But in the late 1990s the company was in trouble, losing out to the Wintel platform. After Steve Jobs’s return in 1997, he set about recalibrating the company’s innovation system for success. He broadened the ecosystem by engaging Microsoft as a partner, strengthened governance by focusing development on the projects most likely to drive value such as the iMac, and increased ambition by defining new domains for innovation (iPod in 2001, iTunes Music Store in 2003). These moves generated the resources and attracted the talent that fueled Apple’s serial innovation machine, which now—against the odds—outlives its original founder.

An effective innovation system takes time and experience to build. Practice, as well as learning from both successes and failures, is essential. Our list of ten questions does not replace the need for a more systematic assessment. From time to time, a company needs to reassess and revalidate all the elements of its innovation system—the “machine that makes the machine”—to ensure that it is delivering maximum value. Still, in our experience, these questions provide a starting point for innovation leaders to build a case for change, rally other stakeholders, and point to a first set of points for action. Successful serial innovators are made, not born.