COVID-19 has significantly disrupted the PE industry in Asia-Pacific (APAC), but it doesn’t alter the industry’s promising long-term growth prospects. In fact, it could create opportunities for funds that understand the characteristics and trends of PE deals in the region and are willing to be bold.

Success requires a deep understanding of the region’s characteristics and typical deal patterns during the period of strong growth prior to the pandemic, as well as a clear sense of how those factors have changed as a result of COVID-19. Some new sectors and investment themes are emerging. In other instances, opportunities that were attractive before the pandemic are even more so now, due to reduced valuations, faster growth, or other factors. In the past, PE investors in APAC created value primarily through debt financing and multiples arbitrage—that is, through largely financial strategies. But to win in the future, they will need to create teams and networks that can make large-scale operational changes with the potential to unlock significant value in portfolio companies .

We are bullish about the long-term prospects for PE in APAC once the crisis is behind us. And we believe that firms with the right capabilities in place and willingness to be bold will capitalize on the once-in-a-generation opportunity that the next several years present.

Strong Growth Leading Up to the Crisis

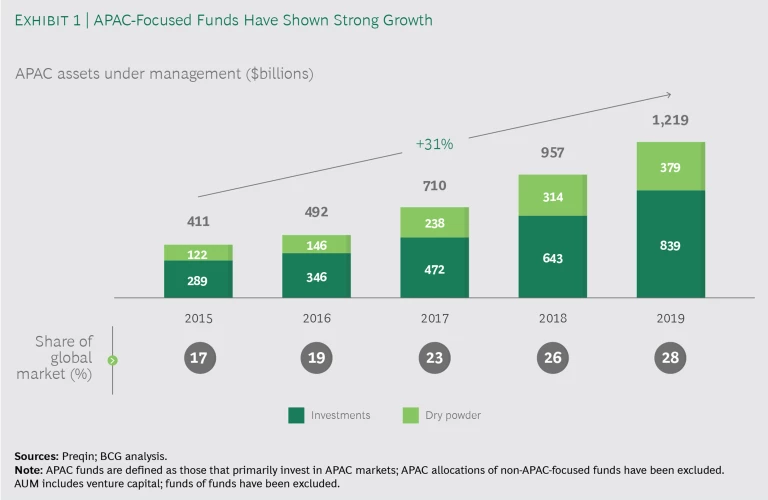

The PE industry in APAC has shown robust growth over the past five years across all key metrics. Assets under management for APAC-focused funds grew at an annual rate of 31% from 2015 through 2019, versus 12% for funds focused on North America and Europe during the same time

APAC has seen companies raise nearly $800 billion in funds during this time frame. The average size of private equity funds in APAC grew larger, too, from approximately $210 million in 2015 to $630 million in 2019 (excluding VC funds, which are smaller by design).

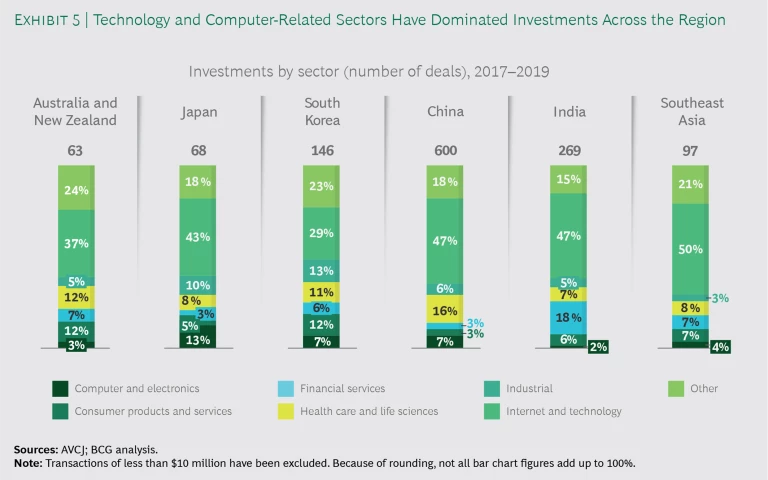

Overall, growth-oriented funds have claimed the biggest share of PE funds raised in APAC recently, for a good reason. As governments in the region—particularly in India and China—modernize infrastructure and encourage entrepreneurship and technological innovation, the opportunities for growth funds to capitalize have increased. Buyout funds’ share of fundraising grew from about 12% of the market in 2016 to roughly 28% in 2019. For buyout funds, the more promising markets are in mature economies such as Australia, Japan, and South Korea, where succession deals and carve-outs present opportunities. In terms of sectors, technology-oriented funds have shown dramatic growth, with $136 billion in total fundraising from 2015 to 2019, compared with $48 billion from 2010 to 2014. In 2019, for example, SINO-IC Capital, backed by the Chinese government, raised a $30 billion fund dedicated to the integrated circuit industry.

From 2015 to 2019, APAC saw more than $850 billion in total PE investments, including a high of more than $200 billion in

Key Interregional Differences

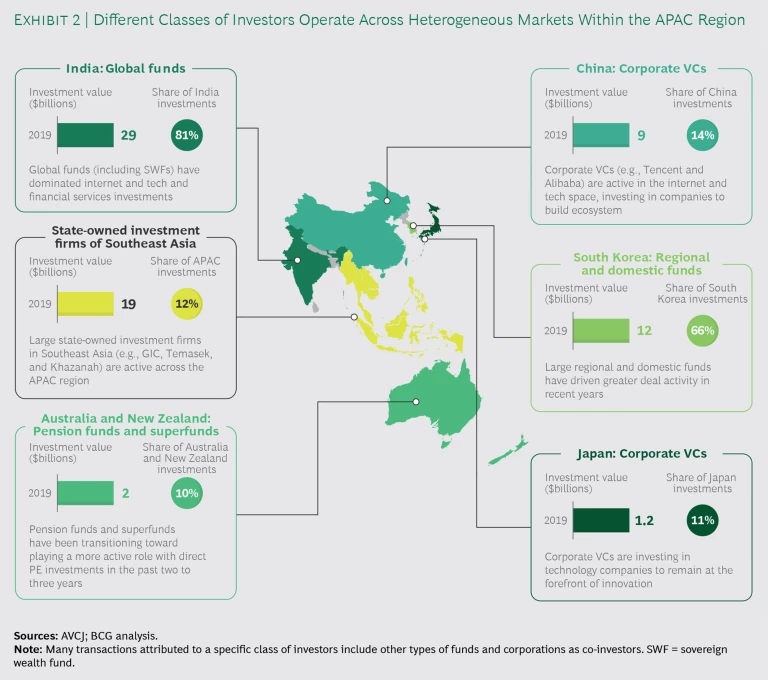

The PE market in APAC is not homogeneous. Each country and region has its own characteristics, and each has evolved in its own way over the past several years. The most notable changes relate to types of fund classes, investment dynamics, and exit strategies. (See Exhibit 2.)

Differences in Fund Classes Across the Region. Large pension funds have been more active in Australia and New Zealand, transitioning from a relatively passive fund-of-funds model and limited partnership positions to an approach that involves playing a more active, hands-on role with direct investments. For example, AustralianSuper participated with BGH Capital in a $1.5 billion takeover of education group Navitas in 2019. Early redemptions due to COVID-19 (which are expected to exceed $20 billion) are likely to exert greater pressure on pension funds in the region. That will require them to cover fund costs with a lower asset base, which may lead to mergers that allow funds to generate scale efficiencies and gain the resources to do larger deals.

In Southeast Asia, state-owned investment firms such as GIC and Temasek (in Singapore) and Khazanah (in Malaysia) have been increasingly active in cross-border investments. In 2019, these investors had some level of participation in 12% of all deals across the APAC region, by value, up from 6% in 2017. That concentration is even more pronounced in India: 48% of all deals involving such investors in 2019 were for India-based companies (accounting for $9 billion in deal value), compared to 17% in 2017 ($2 billion).

Corporate venture capital funds have been more active in China and Japan, investing heavily in startups and high-growth companies as the local technology ecosystem in the region evolves. For example, the venture arms of Chinese internet giants Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent have participated in about $10 billion worth of deals over the past three years across China and India.

Corporate venture capital funds in China and Japan have invested heavily in startups and high-growth companies.

Finally, the contrast between two of the region’s largest markets—South Korea and India—illustrates the heterogeneous nature of the region’s investment market. In South Korea, regional funds such as Affinity, IMM, and MBK are strong; 66% of the deals by value in 2019 involved regional and domestic funds, as large regional funds increased their allocation to the country. India, on the other hand, is dominated by global funds, including large state-owned investment firms, which participated in more than 81% of deals, by value, in 2019.

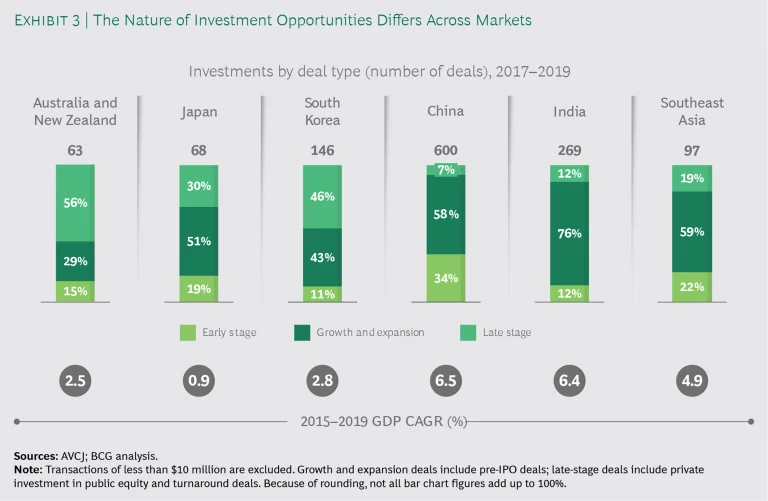

Differences in Investment Dynamics. Typically, the share of investments in mature companies tracks the maturity of the economy as a whole. (See Exhibit 3.) The slower-growing economies of Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand are home to large diversified conglomerates and have historically witnessed multiple divestitures of entire divisions, business units, or country-specific entities, creating opportunities for large buyout funds and consortiums. For example, Toshiba divested its memory division in a high-profile, $14.7 billion deal in 2017 to a consortium of investment funds and corporations; and Hitachi divested Hitachi Koki, its electric tools and equipment business, to KKR in 2017. In contrast, developing markets such as India, China, and Southeast Asia have seen a higher proportion of growth investments, largely in the internet and technology space.

Another factor distinct to the APAC region is the prevalence of small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) and family-owned businesses, with a large overlap between the two. SMEs comprise over 90% of enterprises in the APAC region and employ nearly 50% of the workforce, and in some markets the numbers are even higher. In Japan, for example, SMEs make up about 99% of all companies. As Japan’s population ages and business owners there retire, many face a lack of heirs who can take over the business. As a result, investors are seeing an increasing number of buyout opportunities in the country.

As Japan’s population ages and business owners there retire, investors are seeing an increasing number of buyout opportunities.

At the same time, family-owned businesses in APAC are becoming more receptive to private capital. As of 2018, China, India, South Korea, and Thailand all ranked in the top 10 countries globally for number of family-owned businesses with market capitalization of over $250 million. In the past, owners of such businesses, especially in India, have not been inclined to accept funding from PE investors, because they typically view such investors as being more interested in generating a rapid return than in improving the company’s long-term performance. As family businesses look at growth and expansion, however, they are increasingly exploring funding through sale of minority stakes.

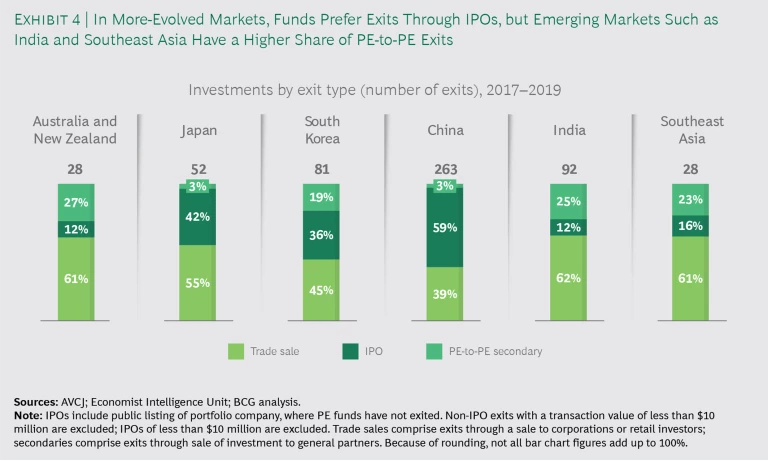

Differences in Exit Strategies. The exit strategy for a fund varies depending on multiple factors—most notably the maturity of a country’s public markets, strategic buyers’ appetite for M&A, and prevailing macroeconomic conditions. For example, Japan, China, and South Korea have seen a higher share of IPO exits over the past three years. (See Exhibit 4.) Australia and New Zealand, by contrast, have had a checkered history of exits via IPO, and IPO exits therefore continue to be low.

Regulatory requirements are a factor as well. In India, strict rules limit the pool of companies that can go public. (For example, companies that have yet to generate a profit are not eligible.) Similarly, China has seen a decline in the number of PE-based IPOs, from 280 in 2017 to 86 in 2019, primarily because of new regulations that aim to improve the quality of listings in order to protect investors through selective IPO approvals. In response, some funds in China have shifted to alternative exit strategies, including trade sales and IPO listings in other countries. For example, Alibaba made two public offerings: one in the US, in 2014, raising $21.8 billion; and one in Hong Kong, in 2019, raising $12.9 billion.

Changes in Investment Opportunities Due to Covid-19

COVID-19 is driving changes in consumer and social behavior as well as in purchasing patterns. For example, pressure on personal finances is reducing discretionary spending on purchases such as automobiles and luxury goods. Social distancing, driven by health concerns and government-mandated lockdowns, is turning consumers toward internet-based, at-home solutions for both work and leisure. This has accelerated adoption of digital channels such as e-commerce, digital media, and digital payments. Although many of these trends had already begun gaining momentum in APAC prior to the pandemic, COVID-19 has given them a considerable boost. (See the sidebar.) As a result, new investment opportunities are emerging.

Key Growth Trends That COVID-19 Has Accelerated

- Growth in digital platforms that allow people to conduct much of their normal activity from home, including such areas as entertainment, education, payments, and home services

- Continued adoption of e-commerce and online-to-offline business models, especially for nontraditional sectors such as grocery staples and fresh food

- Stronger demand for tools that allow people to work from home, including connectivity, collaboration, and shared experiences

- An acceleration of health and wellness tools and services such as telemedicine, cloud physicians, online pharmacies, and fitness services

COVID-19 has positively affected some previously strong sectors, such as health care. Prior to the crisis, the health care sector in APAC was growing rapidly, driven by aging populations in some markets (Japan, South Korea, and Australia and New Zealand) and increased affluence leading to more spending on health care in others (India, China, and Southeast Asia). The share of health care investments in China, by value, has grown from 5% in 2017 (nearly $5 billion) to 12% in 2019 (almost $8 billion). However, the pandemic has sharpened the focus on the industry and spurred deals. During the first four months of 2020, 69 health care deals were closed in the APAC region, including 47 in China alone. That is up nearly 50% over the same period in 2019. (See Exhibit 5.)

Telehealth and online pharmacy businesses are seeing strong growth, too, as consumers require health care services while at home and governments seek to relieve pressure on strained hospitals and clinics. The convenience of these models makes them likely to stick. Baring Private Equity Asia acquired a 14.5% stake in JD Health, a telehealth and online pharmacy platform in China. Although this deal closed in May 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it could be a harbinger of similar transactions in the future.

COVID-19 has helped accelerate some emerging technology trends in APAC. COVID-19 has accelerated the rate at which consumers are adopting technology-driven solutions in everyday life, presenting new opportunities for investors. For example, education technology grew fast during the previous five years, especially in China and India, but its growth has accelerated as many parents have tried to compensate for the closure of schools during COVID-related lockdowns. Byju’s, an Indian player, is now the world’s most valuable ed-tech company, with a valuation of $10 billion in its May 2020 funding round.

COVID-19 has accelerated the rate at which consumers are adopting technology-driven solutions in everyday life.

Digital payments are another example. The e-payment sector had been expanding quickly in APAC over the past five years, in part because of high smartphone penetration rates and wide 4G coverage in the region. But COVID-19 has given it further impetus, as consumers have had to make payments without using cash or having access to bank branches. Consumer studies in India indicate that 42% of consumers have increased their usage of digital payment methods since COVID-19 took hold.

A key solution applicable in virtually every industry is artificial intelligence (AI). That sector has been hot for the past few years, but it has received a further boost due to the digitization push resulting from COVID-19. The first four months of 2020 saw 23 AI investments in APAC that raised a total of $866 million, a significant increase over the preceding four months, in which 20 AI investments raised $755 million.

Behavioral shifts due to COVID-19 are creating new investment themes. COVID-19 has changed the prospects of several other sectors with nascent trends prior to the pandemic. For example, cybersecurity and connectivity apps and services are likely to become more important as working from home becomes more common. Prior to the coronavirus, the trend of working from home was relatively limited in APAC. Because many APAC economies have been traditional destinations for contact-centers and business process outsourcing, shifts to working from home can impact a large proportion of employees there.

EXL Service, an American operations management and analytics services company, plans to shift 25% of its Indian workforce to a permanent work-from-home model in the near future, and Tata Consultancy Services in India expects 75% of its workforce to be able to work from home by 2025. That shift will trigger a growing market in tools and technologies to support people working from home. Zoom Video Communications added more than 183,000 enterprise customers in the first quarter of 2020 and grew at 350% compared to the prior year. In May 2020, to make its services more secure, the company acquired Keybase, an encrypted messaging startup. Alibaba’s Dingtalk and Tencent Meeting—both of which offer videoconferencing—have been two of the most downloaded iOS apps in China in 2020. Tencent Meeting was launched very recently, in December 2019, but it amassed 10 million daily active users in its first two months.

Lower valuations make some sectors more attractive. Another key way that COVID-19 is changing the investment market in APAC is by reducing industry valuations. Any sector or business model that relies on the physical movement of people, in-person transactions, or a high degree of social contact has lost significant revenue as a result of coronavirus-related lockdowns. The valuations for these sectors are all down significantly, reflecting temporary concerns that could encourage an overcorrection. Moreover, businesses that lack a strong liquidity cushion may be forced into a sale, making them attractive opportunities for investors.

Airlines have been among the worst hit companies, with share-price declines of 70% or more for carriers such as United, and bankruptcies at Avianca and Virgin Australia. The sector will recover gradually, with domestic air travel returning before international travel does. Accordingly, domestic-focused airlines with low fleet repayment costs could be attractive. In this spirit, the sales process for Virgin Australia, an airline heavily focused on the domestic Australian market, attracted interest from about 20 bidders, with Bain Capital eventually winning.

Other sectors experiencing lower valuations include automotive manufacturers—which have lost nearly $130 billion in revenue worldwide—along with cinemas and retail. Some of these sectors will recover, and within each sector, certain business models are more likely to lead the pack. In the near term, significant gaps in valuations between buyers and sellers may continue. For deals in these sectors to pick up, either the gaps must close or potential targets must experience even greater economic pain, reducing their negotiating power.

Sectors temporarily experiencing sharply lower valuations include airlines, automotive manufacturers, cinemas, and retail.

New opportunities to invest across types of deal structures are emerging as a result of COVID-19. In addition to making some sectors more attractive, the coronavirus is changing the nature of opportunities available across types of deals. As conglomerates face a cash crunch and compressed valuations, we are likely to see a trend of carve-outs, as corporations focus on their core assets to revitalize their business and counter liquidity challenges. This will create opportunities for funds that have typically preferred control deals.

Like corporations, family-owned businesses are feeling stress from COVID-19, but the effect for them is magnified because their personal wealth and their income are deeply tied to their business. Such business owners will be more open to private capital than ever before, as they look to shore up their liquidity to weather the pandemic and sustain their business. This will give investors many more opportunities than in the past to take minority stakes in such businesses.

Because family-owned businesses in APAC are often highly leveraged, the stress they experience during the crisis will be compounded. Some family-business owners may be open to relinquishing control in exchange for immediate support in managing debt obligations and charting a way through turbulence despite unfavorable valuations. Likewise, in markets with aging population such as Japan and South Korea, COVID-19 will accelerate succession control deals, as SME owners lacking planned heirs seek external support to turn around their businesses and maintain their hard-earned legacy.

The divide between winners and losers will widen. Within sectors, companies that are uniquely positioned or have a robust business model will become much more attractive to investors. For example, India’s Jio Platforms, a digital services company, has attracted more than $20 billion, nearly half of it in PE investments, over the past few months. Investors have a positive view of the company’s potential to leverage its vast telecom subscriber base and its network of physical retail outlets to transform the country’s digital ecosystem.

Funds with portfolio companies that are well positioned to navigate the crisis will try to capitalize on their advantage. They will leverage these portfolio companies to consolidate the industry through horizontal or vertical integration. By consolidating their position and expanding their theater of operations, successful portfolio companies can help their PE investors reinforce their advantages over the competition.

Debt finance may become scarce. The relative share of debt in the capital structure of deals is likely to fall—and where it does not, lenders will enforce stricter covenants to protect themselves. Therefore, investment theses need to be stronger to justify the higher level of equity that will be needed. As the typical value-generation route of using leverage becomes less common, funds must have high degree of conviction about potential EBITDA improvement in their target companies. Banks are likely to direct any incremental loans toward safer recipients, as opposed to funds for buyouts. Similar trends occurred after the global financial crisis in 2008. Investors will not want to saddle their acquisitions with unsustainable levels of debt, especially when business performance is so uncertain through the COVID-19 recovery.

Banks are likely to direct any incremental loans toward safer recipients, as opposed to funds for buyouts.

Holding periods will likely get longer, and funds will need to rethink their exit strategy. In terms of exits, the pandemic is likely to increase holding periods. Lower-than-expected valuations might persuade funds to hold on to their investments in anticipation of a post-COVID-19 recovery. Market liquidity is also likely to be lower because of the pandemic, at least in the immediate future, with funds finding fewer potential buyers in the price ranges at which they would consider selling. Yet another reason for longer holding periods is the risk of negative exchange-rate movements for emerging market currencies, as investors flock to the safer haven of the US dollar. Such a trend would further depress valuations for global investors, making the internal rate of return for a PE owner even less attractive. As funds hold on to investments for longer periods, some are likely to use operational levers more proactively to create value.

As a result of increased volatility and reduced stock market valuations worldwide, the share of IPO exits across all APAC markets is likely to decrease. Funds will need to prudently plan their exit strategy earlier in the investment life cycle and tailor their approach to the strengths of an individual holding. For example, public investors may favor a portfolio company that has a high degree of digital maturity or a unique proposition, making an IPO more likely. At the same time, in an environment with fewer IPOs overall, funds should engage with prospective buyers much more closely to capitalize on any opportunities that may arise. Regional and domestic funds may be able to exit some positions through secondary sales to global funds that are looking to increase their exposure to APAC.

How Funds Should Prepare

In this uncertain environment, funds should consider taking several steps to maximize their chances of success.

Build new team capabilities. Traditionally, funds in APAC have focused on building strong transaction teams and creating value through financial levers. In the post-COVID environment, however, funds will need to be able to make operational changes within companies to unlock value. To that end, funds in APAC should carefully assess their existing capabilities to make operational changes, identify gaps, and determine when to fill those gaps using internal resources and when to tap into external expertise.

In the post-COVID environment, funds must make operational changes within companies to unlock value.

For example, for truly cross-industry and cross-portfolio areas that need ongoing attention—such as scenario planning, demand forecasting, and leadership development—funds should build internal capabilities. But for specific value creation topics within individual companies—for example, cost efficiency; digital transformation; cybersecurity; and compliance on environment, social, and governmental issues —funds must build a network of trusted advisors. This network can include technical advisors, consultants, former senior industry executives, and industry professionals such as bankers and lawyers.

Funds should also define a clear engagement model between themselves, portfolio companies, and advisors, while remaining cognizant of the tradeoffs across such models. Funds can choose to be deeply involved, shaping and steering the work and guiding portfolio companies on scope and goal setting, or they can play a more hands-off role by acting primarily as facilitators.

Leverage digital to cast a wider net in deal sourcing and in due diligence. Successful deal sourcing in APAC will require leveraging digital tools and analytics to scan the market. Some APAC regions have low-quality data, but understanding the different sources of data and making sound interpretations on the basis of limited information are critical to forming an investment thesis.

To identify potential targets, funds should analyze publicly available unstructured data—such as social media posts, customer mentions, and reviews—to identify latent needs and emerging trends. This approach can help identify sectors that are likely to have a positive outlook in the future. Within chosen sectors, funds must use all available databases to run deep market scans to minimize the chance of missing potentially attractive targets. Funds can then use further analytics keyed to specific variables to drill down within sectors, at a company level, to identify a tangible set of potential targets that are consistent with solid investment theses.

A similar approach applies to due diligence. Funds must leverage a mix of proxy data sources, digital analytics tools, and social listening to identify potential areas of value, a company’s brand position compared with that of its competitors, and prevailing consumer sentiment. This information can help funds validate company-specific and market-specific assumptions used in valuation models. As the emphasis on value creation and buyouts grows in APAC, it is important to frame a fund-wide strategy, tailored to each individual APAC market, to develop an approach to operations and digital diligence during the phases of commercial and financial due diligence. As digital transformation is becoming a critical means of creating value at portfolio companies, funds should create standardized frameworks for assessing the digital maturity of target companies during diligence.

Funds should create standardized frameworks for assessing the digital maturity of target companies during diligence.

Be pragmatic in leveraging digital for value creation. Portfolio companies will have varied degrees of digital maturity, and funds must articulate a clear digital strategy that encompasses which products or services to digitize, which data and analytics use cases to advance, and which supporting technology infrastructure to build.

COVID-19 offers funds an opportunity to accelerate the digitization of core processes. Table-stakes examples include robotic process automation in service centers and back-office processes, and digital sales channels for companies operating in the retail sector.

However, funds must embrace digital more boldly if they are to leapfrog competitors. For example, setting up digital centers and incubation labs at a fund level can give portfolio companies the right platform to rethink the customer experience, create disruptive business models, and harness technology for innovation. Funds may appoint a chief digital officer (CDO) to oversee the application of digital initiatives across portfolio companies. But funds must be prudent in assessing CDO capabilities to ensure that they can properly align the digital initiatives with the portfolio company’s strategic priorities and existing business operations.

Continue crisis management best practices initiated in response to COVID-19. As funds continue to respond to COVID-19, many have rolled out a strong set of proactive measures. Even as the crisis eases and funds return to business-as-usual operations, some of these practices should be continued.

A strong focus on cost and liquidity management has helped funds ensure the viability of distressed portfolio companies. Continuing this mindset by setting up cash management offices or committees to regularly monitor spending levels, for example, can ensure that companies stay lean and financially healthy. Funds must also continue to conduct scenario-planning and demand-forecasting exercises that consider all possibilities, including outlier events, and judiciously act on any insights.

Certain funds have used the crisis as an opportunity to increase the level and improve the quality of their engagement with portfolio companies’ leadership teams. Keeping regular channels of communication open and continuing to build trust can ensure that all stakeholders remain aligned. Similarly, some funds have increased their collaboration and sharing of best practices, to generate synergies among the companies in their portfolio. This will remain important beyond COVID-19, particularly for industry-focused funds. For example, funds can look at combining procurement processes to enable their portfolio companies to build scale and reduce costs.

Be ambitious, and don’t waste the crisis. Last, funds should be ready to act swiftly so that they can complete deals in positively affected sectors where competition is high, or in negatively affected sectors where sellers are motivated. This requires early framing of investment theses, tight monitoring of metrics across targets, and a readiness to invest quickly when the opportunity is ripe. This is the time for portfolio companies to actively pursue acquisitions and to consider divesting businesses to strengthen the overall company. Greater ambition will be rewarded at both the fund level and the company level. Crises such as COVID-19 present a rare window of opportunity to mobilize organizations for large transformations across products, services, customer interactions, and core operations. In a BCG survey conducted in North America in June 2020 , 90% of investors said that they believe it is important for companies to prioritize building business capabilities for advantage and growth, even at the expense of earnings per share.

Even before the pandemic hit, APAC was a vibrant and exciting market for PE firms. COVID-19 has not changed that, despite the accompanying economic slowdown—but it has raised the stakes. Some companies and segments are growing faster today than they were six months ago because of emerging trends and changing consumer behaviors. Reduced valuations are making other sectors attractive as well. Within sectors, as economies emerge from the pandemic, there will be clear winners and losers. For funds, the challenge is to be bold and make the most of this unique opportunity. Success won’t be easy, but for funds that understand the characteristics of investments in the region, adapt their investment decisions to reflect the changes that COVID-19 has brought on, and take steps to build the right capabilities, the region’s future looks bright.

The authors would like to thank Kshemu Desai, Udit Gadkary, Aayushi Garg, and Yuvraj Singh for their support in preparing this publication. They would also like to recognize the regional and industry insights provided by BCG colleagues Michael Brigl, Roy Huang, Seoha Kim, Vinay Shandal, Ben Sheridan, Mark Wiseman, and Yue Hong Zhang.

They thank Allister Noronha for conducting research and Jairam Janardhanan, Dogyun Kim, Ryuji Sakaue, and Tian Yu for validating data.

In addition, the authors are grateful to Katherine Andrews, Kim Friedman, Jeff Garigliano, Abby Garland, Steven Gray, Eva Klement, Kate Myhre, Shannon Nardi, and Franziska Weyer for assistance in writing, editing, design, production, and marketing.