Dealmakers should anticipate that the COVID-19 crisis will add to the complexity of regulatory approval. They should prepare for a slower clearance process in the near term and expanded regulatory scrutiny of deals over the long term. The pandemic has, understandably, affected the operations of regulatory authorities. The impacts vary by jurisdiction and include temporary closures, slower processing times, changes to mandatory deadlines, and requests to delay merger filings. Moreover, key factors that affect merger clearance for large deals—anticompetitive concerns, national security issues, and geopolitical considerations—have become more important.

Companies that are currently engaged in M&A or that anticipate pursuing deals in the near term must understand how the crisis is affecting merger clearance, both operationally and with respect to the level of scrutiny and the required remedies. They can then apply this understanding to optimize their interactions with regulators and address five issues that may impact a deal’s economics: the regulatory risk associated with the buyer, the potential for synergy loss due to merger clearance remedies, the need to divest assets at fire-sale prices, the prolonged uncertainty and lost business momentum resulting from extended approval times, and the need to ring-fence assets pending divestment.

How Is COVID-19 Affecting Merger Clearance?

Although it is too soon to fully assess the long-term consequences of COVID-19 on M&A, deal-making activity in the near term has naturally been affected by the deterioration of capital markets and the real economy. M&A activity has declined , with a greater emphasis on acquisitions of distressed businesses by those companies strong enough to weather the economic storm. Indeed, downturns often present opportunities to create value through M&A.

In addition, as of this writing, the operations of regulatory authorities have been disrupted by the crisis. Although the situation is quite fluid, in many jurisdictions, leaders and staff members are working from home, which means that any interactions with dealmakers and their representatives are occurring via video, telephone, or email. Some authorities have shifted to, or are making greater use of, electronic filings instead of paper-based submissions. For example, US regulators have implemented a temporary electronic filing system. And regulators are finding it challenging to collect market information from relevant parties—such as customers, suppliers, and competitors—to assess merger clearance requests. As a result, European Union (EU) regulators have encouraged dealmakers to postpone filings, when possible. In contrast, regulators in China have resumed normal operations and implemented accelerated review processes for certain industries that are critical to addressing the challenges arising from the crisis or that have been hit especially hard.

Resuming normal operations with an emphasis on accelerated reviews for high-priority deals will be crucial in other jurisdictions as well. In the coming months, we expect to see a higher proportion of distressed deals in which sellers are acquired by financially stronger competitors. To address antitrust concerns, the parties may seek to persuade regulators that an acquisition will actually promote, rather than reduce, competition by enabling the continuation of a business that would otherwise fail.

Cross-border deals may see heightened scrutiny as countries introduce or expand so-called foreign investment approvals.

Cross-border deals may see heightened scrutiny as the crisis reinforces the recent trend of countries introducing or expanding the use of so-called foreign investment approvals to protect businesses deemed to be of national interest. Regulators have blocked a number of prominent deals because of national security concerns. For example, in 2018, the Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States (CFIUS) blocked the acquisition of chipmaker Qualcomm by Broadcom, which was then based in Singapore. Subsequently, the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) gave CFIUS additional powers to investigate and block foreign acquisitions of US companies. Given that the crisis has caused significant disruptions to supply chains, including those for critical medical supplies, dealmakers should anticipate that regulators will take a broader view of which acquisitions constitute a threat to national security. Indeed, the EU has encouraged member states to use foreign investment approvals to scrutinize deals involving critical health infrastructure and medical supplies.

The crisis-related complications add to the challenges of merger clearance that experienced dealmakers are already familiar with. In some cases, regulators require significant divestments to help preserve market competition. This was the impetus for the remedies required for approval of the asset swap between the pharmaceutical giants GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis in 2015.

In other cases, regulators block deals because the remedies proposed by the parties are deemed insufficient. In 2019, for example, EU regulators formally blocked the proposed joint venture in the steel industry between thyssenkrupp and Tata. To address anticompetitive concerns, the parties had agreed to divest a portion of the business that was related to auto body sheet metal production. However, regulators were not satisfied and wanted them to divest production in other steel categories as well. Ultimately, the parties said that the requested concessions “undermined the logic” of the joint venture and refused to agree to them.

In still other cases, regulators block deals outright. In 2019, EU regulators blocked the acquisition of Alstom by Siemens after concluding that the merger would harm competition in the railroad equipment industry.

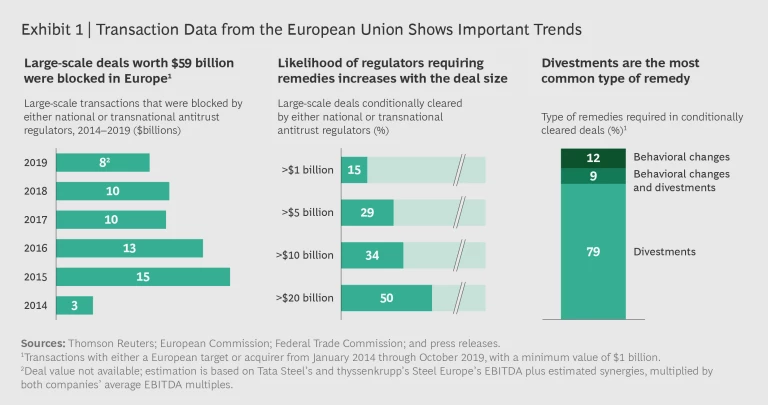

We analyzed deals of European companies from 2014 through 2019 and found that EU regulators blocked large deals that had a combined value of almost $60 billion. As would be expected, the likelihood of remedies being required increased with the size of the deal. Divestments are the most common type of remedy. (See Exhibit 1.) We see similar trends in the US.

Effectively Navigating the Process

Against this backdrop of increasing complexity and scrutiny, companies must be ready to proactively preserve the economics of their deals as they navigate the merger clearance process. The agenda should include the following set of actions.

Take steps to enhance deal certainty. In a competitive auction, a seller may, all else being equal, prefer a bidder that is less likely to raise regulatory concerns, thus increasing the certainty of deal approval. Some buyers’ attributes increase the risk that the regulatory process will be prolonged or that the deal will be blocked or fall apart because the parties cannot agree on remedies. To compensate for higher regulatory risk, a buyer may need to bid at a premium price to acquire the target. Because the COVID-19 crisis may impact how regulators assess deals, it adds another element of potential regulatory risk for the parties to consider.

Buyers can find ways to promote certainty. For example, some prospective buyers that anticipate regulatory concerns have partnered with another bidder that will acquire the part of the target’s business that may be a source of regulatory concern. This type of structure may alleviate the seller’s potential misgivings about deal certainty. However, such deals are inherently complex to craft. Further, they may require the original buyer to offer a financially attractive deal to its bidding partner, thus eroding the economics of acquiring the target.

Understand how potential remedies would affect synergies. Achieving cost and revenue synergies is usually a fundamental aspect of a deal’s rationale. If, in order to get merger clearance, the parties must divest a portion of their businesses—or otherwise exclude it from the merged company—then, by definition, there will be fewer overlapping businesses to integrate and thus less synergies to achieve.

Although the COVID-19 crisis is unlikely to have a direct impact on synergies, there may be indirect impacts if the crisis affects regulators’ decisions about the scope of remedies required—for example, excluding parts of the businesses from the deal for national security reasons. Even before the crisis, as noted above, the divestments required as remedies by regulators often diminished the value of announced synergies or, in extreme cases, completely undermined the deal logic.

Experienced buyers anticipate how the regulatory process will affect synergies. They perform a comprehensive synergy analysis that is typically broken down by business, function, and region. In addition, they consider how the synergies will be affected by various regulatory scenarios—such as a requirement to exclude a certain business or country unit from the merged company. In one case, the potential buyer built a detailed outside-in model of synergies that facilitated exploring a variety of regulatory scenarios and the associated financial implications. For each scenario, the model included the value creation potential and the one-off costs of divestitures required as remedies. This modeling, in turn, helped to inform a proactive regulatory strategy that balanced the value creation goals with regulatory risk considerations.

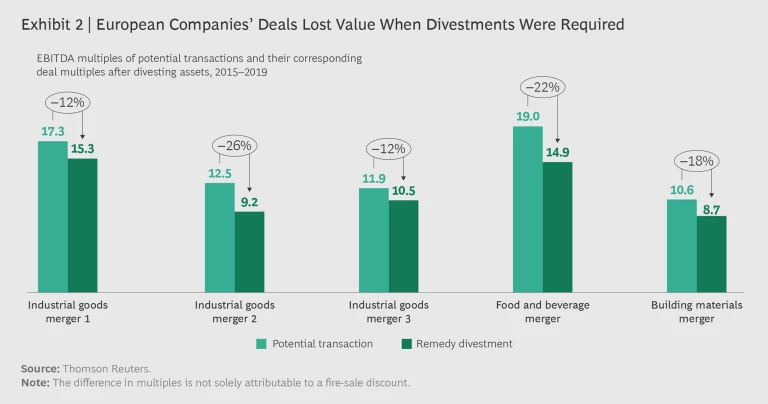

Evaluate how fire-sale divestments will affect value creation. We have seen buyers lose significant value because they needed to divest assets in order to comply with clearance remedies. (See Exhibit 2.) If the current crisis dampens companies’ appetite for acquisitions, the value lost owing to divestments, especially those made at fire-sale prices, will likely rise.

In a recent health care merger, EU regulators required the buyer to divest a drug and the associated business operations—including, potentially, commercial operations, R&D, and manufacturing capabilities. The exact scope of the divestment would depend on which company was acquiring the drug. Although there were a number of potential acquirers, regulators determined that one company was particularly well positioned to preserve competition. The price ultimately paid by this company was less than half of the buyer’s original estimate of the drug’s enterprise value.

Buyers must determine the additional synergies and value creation that are needed to compensate for any fire-sale discounts in order to secure merger clearance. For example, if a business with a nominal value of $500 million is sold for $260 million, then additional annual synergies of approximately $20 million are needed to negate the fire-sale effect. (This assumes an EBITDA multiple of 12x, which is the long-term average across industries, and does not take into account any costs incurred to execute the transaction.)

To reduce the risk of a heavily discounted sale, a company should run a robust remedy divestiture process.

To reduce the risk of a heavily discounted sale and minimize the value leakage, a company should not allow the ongoing acquisition and integration process to distract from the need to run a robust remedy divestiture process. It should approach the process as rigorously as it would any divestiture. This entails developing a well-considered divestiture strategy that includes an analysis of the buyer universe, as well as anticipating the value creation rationale for each potential buyer and the operational scope of a divestiture that would address a buyer’s needs and the regulator’s concerns. Dealmakers should develop strong marketing materials that present a compelling equity story and meticulously prepare for due diligence, management meetings, and negotiations.

Although the parties often devote most of their attention to the acquisition and integration, investing in reducing value leakage from fire-sale discounts may also generate good returns—indeed, it may be more fruitful than trying to squeeze out the last few dollars from synergies.

Monitor dips in business performance while clearance is pending. During the period between the announcement and the closing of the deal, we often see a performance dip. Because of the ongoing uncertainty, many employees may lose focus and become less productive, and some key people may even leave the company. Demand may also decline for various reasons—for example, customers may have concerns about the future of the business or the new owner, the commercial team may lose a high-performing key account manager, or competitors may take advantage of the uncertainty to lure customers away.

In the EU, a phase 1 clearance process nominally takes 25 to 35 working days, but a phase 2 process, if required to assess more complex cases, nominally takes 90 to 125 days. Parties should proactively suggest remedies to regulators so that they can obtain clearance in phase 1 and avoid the long delay entailed in phase 2.

For distressed deals, in particular, it is important to close as quickly as possible. In most jurisdictions, closing a deal without first having approval from regulators (known as gun jumping) is not permitted. However, in some jurisdictions, when time is of the essence, the parties can seek an exemption from the standstill obligations so that the closing can occur before receiving formal approval.

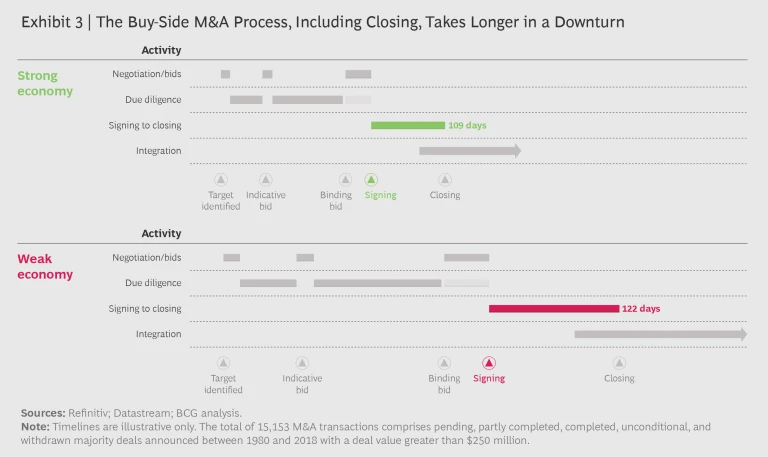

Given the sharp economic downturn, companies should anticipate especially long delays in closing deals. Our research shows that deals (including the period between signing and closing) take longer to execute, on average, during a downturn. (See Exhibit 3.) The COVID-19 crisis will likely further lengthen this timeline owing to the impact of health issues, social distancing, and telework.

In the event of a prolonged period between the deal becoming public and the closing, it is crucial to put in place a monitoring system that provides an early warning of lost momentum in the business, as well as to create a rapid response force to address the underlying problems. To support its surveillance, a consumer goods company created a status dashboard to monitor KPIs. The dashboard presented information gathered through weekly polling of general managers in each market, data from existing management processes (such as the number of sales visits per day, the number of resignations, and unusual changes in order volumes), and information about competitor and recruiter actions.

Consider the costs of ring-fencing businesses to be divested. There are various types of divestment remedies, depending on the jurisdiction. Commonly, buyers can obtain conditional approval for a transaction with the expectation that they will divest the business in question within a specified time period. In other cases, regulators may require a fix-it-first remedy—essentially the parties must find a buyer for the business and enter into a legally binding agreement to divest it as a condition to gaining regulatory approval for the main transaction.

Regardless of the specific remedy, the parties must typically ring-fence the business they are selling if the divestment will occur after the closing of the main transaction. In the EU, for example, this is referred to as a hold separate arrangement. The business to be divested must be separated from the retained business by limiting information flows between the competing businesses and implementing independent governance. The parties must also ensure that they do not treat the ring-fenced business differently or that it does not act differently, such that its competitive position is negatively impacted during the ring-fencing period. If remedy divestitures take longer to execute and close during the COVID-19 crisis, ring-fencing arrangements will need to remain in place longer, which lengthens the period during which certain synergies cannot be realized.

If remedy divestitures take longer to execute, ring-fencing arrangements will need to remain in place longer.

Ring-fencing measures can require making organizational changes—for example, maintaining separate commercial teams and limiting the distribution of reports that contain sensitive data such as pricing. Regulators can also require more-expensive technical measures, such as systems changes to prevent access to sensitive data.

Beyond the costs of setting up and maintaining a ring-fenced arrangement, the separation may impede the companies’ efforts to integrate their operations, thereby slowing the pace at which they can realize synergies from the main deal. That makes it especially important for companies to avoid overkill in ring-fencing. Regulators are often open to pragmatic solutions to keep the businesses separate, but this requires that companies develop a well-considered approach that is clearly communicated to the regulatory body.

Summing Up the Imperatives

Taking into consideration the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on merger clearance, as well as the actions discussed above, buyers can use the following imperatives to guide their preparation and identify improvement opportunities for their capabilities:

- Engage in early and detailed discussions with regulators to understand how the COVID-19 crisis will affect the merger clearance process.

- Anticipate the seller’s concerns about deal certainty, and develop clear, credible solutions—such as proactively partnering with an acquirer for the businesses responsible for the uncertainty.

- Model the synergy impact and costs associated with the most likely remedy scenarios to inform the regulatory strategy.

- Anticipate likely remedy divestitures, and estimate the impact of fire-sale discounts on overall value creation. Prepare as robustly for divesting in this context as you would for any major divestiture.

- Implement early-warning systems to detect the loss of business momentum between the announcement and the closing of the deal, and have a task force ready to address these issues.

- Anticipate likely ring-fencing requirements and the associated costs and synergy implications. Prepare pragmatic solutions—while limiting unnecessary cost—to keep the businesses separate.

- Most important, understand the financial implications of all these issues. Know the point at which the deal no longer makes economic sense—and be prepared to walk away from it.

In the midst of unprecedented uncertainty, it is clear that the COVID-19 crisis has created an additional set of considerations for merger clearance and raised the stakes of navigating the process effectively. Dealmakers that understand the implications and respond proactively will be well positioned to use M&A as a tool for emerging from the crisis as industry leaders.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dominik Degen and Jan Huber for their contributions to this article.