A recent BCG report details a rapidly growing skills mismatch across the globe and estimates that 1.3 billion people have competencies misaligned with the work they perform—including 53.3 million in the US, a number that is surely far higher today due to the pandemic. The unprecedented pace of innovation—especially technological innovation—is largely to blame, and as Covid-19 accelerates the shift to remote, digital work environments, the skills mismatch is widening faster than ever.

That initial report identified a strong need for closer collaboration between higher-education institutions and employers. To understand more, BCG worked with Google to perform an in-depth assessment, including an extensive survey and interviews with business leaders and higher-ed professionals. (See “Our Research.”)

Our Research

Our Research

For this study, we worked with Google before the COVID-19 pandemic to survey 166 US business professionals at the director level or above, including chief HR and IT officers and C-suite executives, all with decision-making authority over recruiting, training, and education benefits. We also held in-depth interviews with 18 primarily US-based higher-education professionals. Although the skills mismatch is a global problem, we chose to focus on the US because it is one of the largest markets struggling with this challenge.

Our research reveals that higher-ed institutions have a tremendous opportunity to step up and help reduce the mismatch. They can do so by initiating deep collaboration with employers in their region to equip the workforce with up-to-date, in-demand competencies. Businesses, in turn, should support this collaboration by investing in their people and working with higher-ed institutions to offer upskilling and reskilling opportunities along a lifelong learning path.

The ongoing pandemic will certainly throw up new obstacles along the path—including uncertainty around student enrollment, changing operating models, and the need for virtual learning at scale—but it has also kick-started the move to online training, which takes less time than in-person efforts, is more cost effective, and has strong potential for future growth.

The Growing Skills Mismatch

Many employers today struggle to keep themselves and their employees on top of the latest skills and technologies, even as higher-ed providers scramble to prepare students for the roles they hope to fill. Although higher education typically provides a good foundation and mindset for pursuing a future career, it can fall short in providing an up-to-date education that aligns with employers’ needs. In fact, only a third of US college students expect to graduate with the knowledge and skills they will need to be successful in the workplace, and just over half believe their major course of study will lead to a good job, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (USBLS). Students also struggle to find the right job after graduation, facing uncertainty about income and employment along with high potential costs for additional training and certification—uncertainty and costs that have only multiplied since the pandemic.

Employees now change jobs—and even careers—more frequently than they used to, hampering employers’ ability to manage long-term learning pathways.

Once hired, many employees must deal with lower productivity and higher costs than in the past, due to the need for additional training. As one higher-ed provider noted, “There is a challenge around job retention in the early years, partly driven by misaligned employer expectations around the knowledge and skills a new graduate will possess.”

Compounding the issue, employees today change jobs—and even careers—more frequently than they used to, hampering employers’ ability to manage long-term learning pathways. On average, a worker holds upwards of ten different jobs before the age of 50, and that number is likely to rise, according to the USBLS. As a result, employee learning is subject to fragmentation and a lack of continuity in the learning life cycle.

Exacerbating the skills mismatch are inadequate career services at higher-ed institutions—or rather, poor institutional promotion of those services. Fewer than 20% of undergraduates reach out to their school’s career centers for advice on finding jobs or identifying and applying to graduate programs, although such advice ranks among a center’s most valuable services, according to a 2017 Strada-Gallup survey of college students. As one educator admitted, “We have good relationships with corporates but are struggling to make our career services really effective—especially due to poor student engagement.”

The US skills mismatch is especially conspicuous in technology, advanced manufacturing, and health care—although it also appears in industries as disparate as construction and financial services. In health care, for example, jobs abound, but professionals increasingly require proficiency in working with advanced technologies such as AI and machine learning.

Time for Higher Ed to Step Up

Given the need for better training in school and in the workplace, we see a tremendous opportunity for educational institutions to come to the fore, not only fulfilling their intended societal role but also boosting student placement rates and entry salaries. As they do, they can generate additional revenues, reduce the role of private recruiting and training companies in the education market, and earn higher rankings and prestige for their institutions.

The opportunity couldn’t be riper right now. According to John Farrar, industry leader for education at Google, “COVID-19 has propelled institutions to remove inertia, accelerating their ability to innovate and experiment. Credential stacking will be the currency of the future for lifelong learners. This is a first mover advantage, and you have all the tools in your toolbox to capitalize on it.”

To succeed, they must collaborate with potential employers across their employees’ lifelong learning cycle. We have defined three core stages in this cycle: preskilling, upskilling, and reskilling. Within these, we have identified several areas of significant opportunity for higher-ed providers. (See Exhibit 1.)

Preskilling for the First Job

Preskilling—providing employees with the skills they require before they begin their career—is exactly what higher-ed institutions were created to do. Yet only 36% of the business leaders we surveyed believe these institutions give their graduates adequate training. There is clearly room and opportunity for institutions to provide a more appropriate and targeted education that meets employers’ needs and prepares students for the jobs they seek.

Today, several private recruiting and training companies hire and quickly train college graduates and then send them to work for corporate partners. These businesses provide a supply of competitive talent to employers, with a focus on free training and better job opportunities for those they hire, sometimes including a minimum wage during the training process.

Underscoring the relevance of this model is the average annual pre-pandemic revenue growth rate of 13% achieved from 2016 to 2019 by the market leader, FDM Group. Increased M&A activity—such as InvestCorp’s acquisition of Revature in February 2019, and Wiley’s acquisition of mthree in January 2020 for £98 million—is an additional indicator.

As a provider in this space tells us, “Our key selling point and reason for our success, frankly, is that we focus on the practical, job-oriented aspects of education, whereas the typical university focuses on the theoretical aspects. Also, they don’t tend to be on the forefront of topics, making their content and materials less relevant.”

Despite the competition, 70% of business leaders in our survey believe higher-ed providers should be more involved in this rapidly growing arena. As one business provider in the space told us, “If colleges and universities step up their game and ensure they have a strong marketing and sales organization in place, and their services roughly match up to ours commercially, I can definitely see them competing with us.” The two leading opportunities for higher ed in this area are first-job readiness and apprenticeships at community colleges.

First-Job Readiness. Our research indicates that 81% of respondents believe that better aligning educational curricula with job openings and skills gaps could resolve the skills mismatch their businesses face. Higher-ed providers should work closely with corporate partners to offer job-oriented short courses in the final phases of a degree, codeveloping a curriculum and materials and aligning these courses directly with corporate needs. They should also engage more closely with businesses in job placement efforts and improved career services.

81% of respondents believe that better aligning educational curricula with job openings and skills gaps could resolve the skills mismatch their businesses face.

Once a few higher-ed providers start pursuing this opportunity, we expect a competitive dynamic to emerge that incites other providers to follow. After all, when students find better jobs, alumni are happier, their salaries are higher, and university rankings improve.

Apprenticeships at Community Colleges. For students with an associate degree, higher-ed institutions should collaborate with corporate partners to establish apprenticeship programs for more hands-on professions such as manufacturing. Apprenticeships offer a lower bar for employers looking to hire in a post-pandemic landscape. The US Department of Labor (DOL) has supported this market by granting $184 million to colleges in June 2019 to support training for over 85,000 apprentices in the fields of health care, advanced manufacturing, and information technology.

To enter this market, higher-ed institutions should identify the appropriate disciplines, articulate the competencies and skills to be mastered, develop a curriculum and credit system, and determine how stakeholders will assist student apprentices throughout the program. In the process, higher-ed institutions should register a degree apprenticeship program with the DOL’s Office of Apprenticeship or with a recognized state apprenticeship agency. Registration can signal that the program meets objective quality standards and will equip apprentices who complete the program with a national, industry-recognized credential.

They should also strive to boost overall adoption of apprenticeship programs, given that, as one educator told us, “The apprenticeship model has to be done at scale—with a higher number of apprentice students across a high number of employers and industries; otherwise, the impact will be too narrow.”

Upskilling for the Long Term

Our research also finds that the traditional corporate training market, with around $150 billion in North American revenues, is not meeting the long-term development needs of corporate leaders, particularly in certain niche areas. Comprehensive training is difficult to source, according to 78% of the business leaders we surveyed, although 83% consider such training to be a priority. As a result, many employees need the kind of new knowledge and skills that higher-ed providers are perfectly equipped to offer. The two leading opportunities for higher ed in this area are short training courses and lifelong learning.

Short Training Courses. More than 88% of our respondents believe higher-ed institutions have good potential to provide training in advanced technical skills, soft skills, and industry-specific knowledge. Compared with other training providers, such institutions have in-house research and expertise, the ability to think through higher-level industry implications, and an expert and alumni network they can gather for facilitated learning sessions with industry experts and corporate peers. As one provider told us, “Based on their particular—preferably distinctive—expertise, universities can offer short trainings that tie to a skills gap in a company and then articulate that into a credit or degree so it’s of clear value to both employee and employer.”

To succeed in this market, providers should identify important pockets of expertise, develop a curriculum and materials in close collaboration with an internal working group and an external business partnership team, and iterate regularly to stay relevant and up-to-date. They should also connect their partners’ employees with counterparts in other companies within the alumni network. For example, Northeastern University recently implemented an online learning platform in partnership with Pearson Publishing and with Practera, a provider of experiential learning programs. The university has also established successful partnerships with both IBM and General Electric, providing training in high tech and in advanced manufacturing systems, respectively.

78% of business leaders say that there is an unmet need for continuous, lifelong learning due to the pace and scope of innovation.

Lifelong Learning. In our survey, 78% of business leaders say that there is an unmet need for continuous, lifelong learning due to the pace and scope of innovation. Higher-ed institutions can work closely with corporate partners to provide this learning for key talent and to map out career pathways, including the knowledge and skills needed at each step and even a timeline for required training and assessments. The process of developing a high-performing accountant or controller into a potential CFO, for example, requires a wide array of soft and hard skills, online and offline learning, and micro and macro formats. Higher-ed institutions can use their knowledge, network, and brand to serve as the constant factor in such an employee’s development.

“Enabling a holistic, lifelong curriculum will be especially interesting for the more prestigious universities, as they will be able to leverage their brand to charge a premium,” one provider told us. And another higher-ed provider noted, “The rise of the lifelong learner is really a key trend. It is even more applicable to certain industries exposed to rapid innovation such as tech and financial services.”

Reskilling to Prepare for New Jobs

The swift pace of innovation has rendered many career fields obsolete and created entirely new ones. This evolution, which repercussions of the pandemic are likely to accelerate, offers an opportunity to reskill portions of the workforce. In fact, our survey indicates that 68% of organizations are investing in reskilling and upskilling their employees. The two leading opportunities for higher ed in this area are corporate training camps and tuition support programs.

68% of organizations are investing in reskilling and upskilling their employees.

Corporate Training Camps. Reskilling often takes the form of short, boot-camp-style training dedicated to teaching critical new skills. Currently, most such training is unaccredited.

Higher-ed providers that wish to enter this market should collaborate with corporate partners to envision future workforce needs, design a course of study, and agree on a learning pathway—including both content and methodology—that will meet the companies’ workforce goals. Even when provided online, training camps typically take employees away from their work, so providers should keep them short but maintain their quality. Providers should also use their admissions expertise to help employers develop an internal pipeline for such training and consider offering accreditation for them.

One large multimedia company, for example, works with an adult education school to take talented women from nontechnical roles across the company and train them to become software programmers. Although the program has a clear diversity angle, its primary goal is to move employees into areas in which the business needs people.

The educational institutions most likely to succeed in providing this type of training are large research universities and technical schools that have the resources to quickly and effectively build intensive courses on emerging technologies, in collaboration with employers that face or expect to face significant staffing shortages, primarily in technical fields.

Tuition Support Programs. In the US, the market for tuition support programs is currently $30 billion, led by Guild Education. (See the sidebar “Provider Case Study: Guild Education.”) Higher-ed institutions have a good opportunity in this area. Such programs are extremely beneficial, especially for employees with an associate degree or lower: employers often cover tuition costs upfront, offer career guidance, handle applications and registrations, and provide flexible class or work schedules.

Provider Case Study: Guild Education

Provider Case Study: Guild Education

Guild Education, the industry leader in tuition support programs, allows employers to use its network of affiliated schools to customize their education programs. These schools offer flexible schedules and formats that work for the employee, an array of choices for improving employee engagement, and various options for upskilling and reskilling. In turn, the schools have access to a large pool of candidates with a relatively secure form of financing from their employers. Although Guild takes a cut of the schools’ revenues, the schools may recoup this expense in the form of lower marketing costs.

Guild helps employee participants set goals and visualize their career paths with coaches who walk them through their options and stay in contact throughout the journey. Employees also have access to an online platform where they can find information about and register for programs that fit their needs. Guild recently acquired The Entangled Group, a “venture studio” focused on the education ecosystem.

The benefits to employers are substantial. The Lumina Foundation has calculated a 144% ROI for the tuition reimbursement program at Discover, for example, and 129% ROI for a similar program at Cigna. Additional business benefits include motivating employees to stay in their positions for the duration of their studies—much longer than the typical tenure for some jobs—becoming eligible for certain federal tax breaks, and being able to shift employees from their current roles to roles that are in greater demand.

81% of business leaders say they would like employee participation rates to rise

In light of these benefits, most employers that are aware of such programs want to boost them. In fact, 81% of business leaders say they would like employee participation rates to rise. Higher-ed institutions can therefore promote these programs directly to employees and to potential business partners. As they do, they should be sure to reach out to business leaders beyond the head of HR—especially those in the C-suite.

Many employees who would benefit from this type of programming will require some convincing, however. Although 60% of the firms we studied offer some form of tuition assistance, only 2% to 5% of eligible employees participate. In explaining the reluctance to take advantage of these programs, respondents cite reasons such as employees’ lack of time outside their work hours, a lack of employer funding up front, inflexible schedules, and employees’ inability to see a connection between the programs and higher pay.

In response, companies can argue that the time invested will result in a promotion, a better career, or a higher salary. One educator says, “Flexibility is key. In some cases, employees work two different jobs and the flexibility to, for example, follow classes in evenings and nights is really important.”

To succeed in this competitive environment, providers should work with companies to optimize program offerings and processes. Employees particularly care about diversified course options, coaching, flexible formats (both online and offline), and a low administrative and financial burden—that is, no hassle around reimbursement, with the employer paying the institution directly.

Three Foundational Pillars

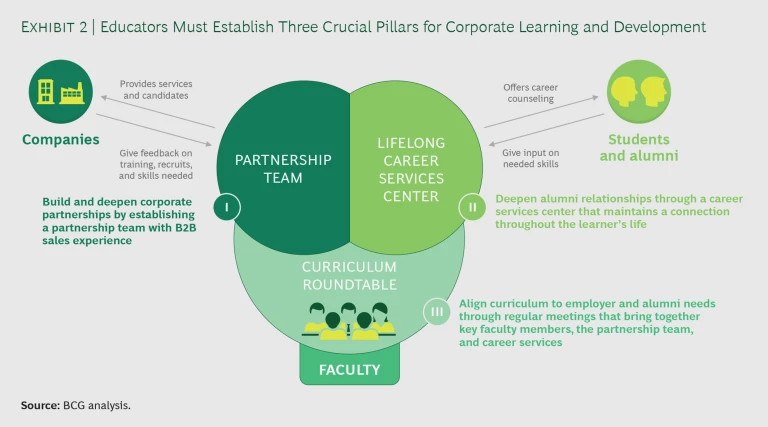

Higher-ed institutions that want to realize these collaboration opportunities must rely on three foundational pillars: an internal partnership team, a lifelong career services center, and a curriculum aligned with employer and alumni needs. (See Exhibit 2.) Specific operational details, such as team sizes and setup times, will vary from institution to institution, depending on such factors as the strength of corporate partnerships, the size of the career services team, and the level of collaboration with faculty on the curriculum.

Partnership Team. The partnership team should consist of individuals with business-to-business (B2B) sales experience who can build and deepen corporate relationships. This team will have three primary goals: to market and sell educational products and services, to place graduates with employers, and to establish a line of communication that generates and maintains robust feedback.

The team should begin by matching a shortlist of target companies to the institution’s areas of expertise and reaching out to those businesses to establish relationships. The business leaders in our survey identified five specific actions as most important for these relationships:

- Be open to codeveloping the curriculum

- Provide high student satisfaction

- Have an online offering

- Deliver niche expertise

- Set up a direct point of contact

Providers’ solutions should offer education throughout the individual’s career, including job-specific training to permit successful entry into the workplace, continued training and development to ensure continuing relevance, and mentorship and guidance to navigate the modern career path. These criteria hold for talent with a bachelor’s degree or higher and for those with an associate degree or lower.

Providers should advertise their value proposition and reskilling capabilities to employers and employees. As one business training provider told us, “I definitely see the opportunity for higher-ed providers, but there is a marketing challenge in having a strong B2B sales force knocking on the doors of corporate HR and learning and development heads that is a prerequisite for success.”

Higher-ed institutions should focus on face-to-face marketing complemented with digital marketing solutions. Although 84% of our respondents point to peers and colleagues as the source of the external providers they hire and 55% point to conferences, others say that digital solutions—such as the provider’s website (for 49% of business leaders), online videos (13%), and online search ads (11%)—are important adjuncts to their decision-making process.

Lifelong Career Services Center. Higher-ed providers should deepen their alumni relationships by establishing a lifelong career services center, expanding the traditional role of career services. Center counselors can begin by closely aligning their goals—including their marketing goals—with those of the partnership team. In addition, they should create and maintain close connections to industry so they can better advise learners on valuable content and skills.

As one educator told us, “The North Star in terms of career services is that employers are embedded into the process from day one of the student’s post-secondary education. This will have key benefits for the employer, as it will be able to better assess talent, etc., but perhaps even more for students, as their learning will be validated, and they will be motivated by that.”

Curriculum Roundtable. In order to agree on a curriculum that suits both employers and alumni, providers should create a curriculum roundtable, or working group, that continually identifies new employer needs and incorporates feedback into the educator’s offerings. Participants at regular meetings should include key faculty members, the partnership team, and career services, and the meetings should entail discussing emerging innovations and how to accommodate them, such as by awarding microcredentials (certifications in specific topic areas) and badges or by establishing indicators of specific accomplishments that others can verify online.

Act Now to Win

Now more than ever, higher-ed institutions need to prepare and develop students and employees with the skills that employers need. They can provide significant value to all parties involved, including themselves, by decisively entering the corporate training arena and collaborating closely with employers to create a better fit between employer needs and the knowledge and skills of students and workers. By doing so, and by supporting lifelong learning initiatives, they will help fulfill their critical societal roles of preskilling, upskilling, and reskilling talent. These efforts will allow them not only to stay relevant but also to regain market share from private recruiting and training companies and generate additional funding for research projects and other needs through the corporate-training revenue stream.

The greater their success, the more employers will recruit their students, the higher their job placement rates and entry salaries will be, and the higher their rankings and institutional prestige will ascend. It’s a true win for all involved.