Like the rest of the oil and gas sector, the North American midstream segment has been rocked by the plunge in global oil demand spawned by the coronavirus pandemic. Since 2020 began, many North American midstream players have seen their market value cut roughly in half, hurt by pullbacks in production by oil and gas producers and a ramping down of capacity by refineries, liquefaction facilities, and exporters.

How can midstream players position themselves for the road ahead? Optimal responses will hinge on each company’s historic performance and current financial health. Many of these businesses face sizable financial challenges; historically, they have demonstrated weak earnings potential or carried excessive debt, or both. These companies should focus on cost optimization, with an eye toward debt reduction, improved capital efficiency, and building capital to fund future growth. A smaller number of companies are in positions of strength, having demonstrated the ability to generate cash while carrying a relatively low debt burden. They should seek to exploit these positions by identifying and seizing growth opportunities.

A Volatile Decade

The steep decline in oil prices in 2020 is the latest blow to North American midstream players during a tumultuous decade. From 2010 through 2014, encouraged by the combination of cheap capital and growing production of shale oil and gas, the companies invested heavily in pipelines and gathering-and-processing infrastructure, with a focus on production centers in North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and Alberta. The companies’ leverage grew from just over four to nearly five times earnings; their capital expenditures grew by roughly 140%.

The group was forced to shift its focus, however, following the plunge in oil prices in late 2014 and the resulting steep decline in share prices that carried into the next year. From 2016 through 2019, companies emphasized deleveraging and more-rigorous capital discipline. These companies’ distribution coverage (cash flow from operations relative to distributions) grew by about 30%, and capital expenditures were increasingly funded by cash flow through operations. The increased capital discipline was also, in some cases, driven by a change in corporate structure. Several companies moved from master limited partnerships to C-corporation structures to lower their cost of capital and streamline investment governance. In recognition of these improvements, analysts entered 2020 guardedly optimistic about the segment’s business prospects.

The pandemic slammed the brakes on midstream companies’ improving fortunes.

The pandemic slammed the brakes on midstream companies’ improving fortunes. Shale operators quickly halted completions and refocused on core areas, reducing their 2020 capital budgets by $6 billion. The number of active rigs in the US has decreased by approximately 70% since the initial market collapse. Oil and gas production fell by 10% from the end of March through June. The effects of these developments have been felt unequally by midstream companies, however; reductions in production have been more pronounced in higher-cost basins, impacting volumes of crude oil, associated gas, and natural gas liquids (NGLs). The number of oil rigs in the Bakken, Eagle Ford, Niobrara, and Permian basins, for example, fell by 50% to 85% from the end of March through June. By contrast, the number of rigs in the dry-gas basins of Appalachia and Haynesville declined by only 20% to 25%. This uneven disruption to midstream businesses is reflected in their stock prices, as large midstream players’ year-to-date share price declines have ranged from moderate (less than 10%) to severe (more than 60%).

AN UNEVEN LANDSCAPE

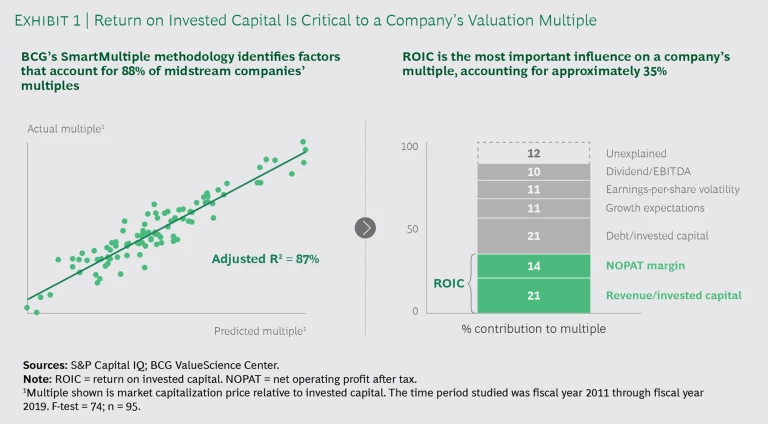

As North American midstream players contemplate their next moves, they should begin by assessing their performance across two dimensions. The first dimension is their historic ability to deliver returns, which we measure using return on invested capital (ROIC). According to BCG’s SmartMultiple methodology, which examines the effects of different operational metrics on multiples, ROIC is a major driver of a company’s valuation multiple and, ultimately, its total shareholder return. (See Exhibit 1.) The second dimension is the amount of leverage employed, with leverage defined as net debt relative to enterprise value. Companies that have performed well on both dimensions will have strategic options their less financially robust peers do not.

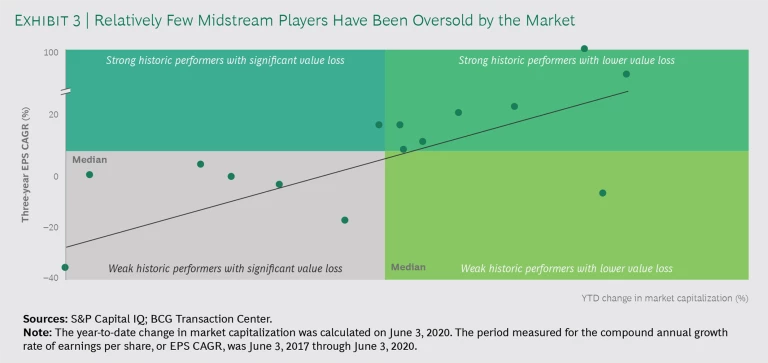

In parallel, midstream players—particularly those in positions of strength—should determine how they and their peers are being valued by capital markets. This will help companies understand whether attractive acquisition candidates are available—or whether they themselves are potential targets. A useful yardstick here is a company’s year-to-date change in market capitalization relative to its three-year earnings per share (EPS) results. We consider companies that have a three-year EPS performance above the midstream median, but valuations that have fallen more than the market, to be oversold.

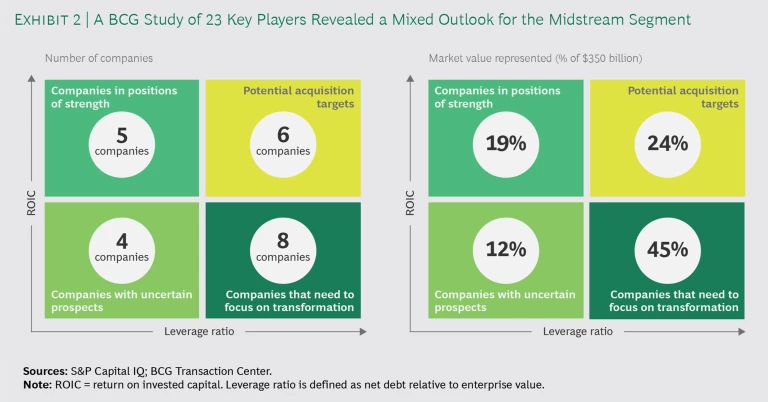

We applied these two lenses—ROIC and capital market valuation—to 23 of the largest North America-focused midstream companies. Combined, the companies represent roughly $350 billion in total market value. Our analysis revealed variance within the group (see Exhibit 2):

- Eight companies—which collectively represent about 45%, or $160 billion, of the group’s total market value—entered the crisis in a vulnerable condition and are even more vulnerable today.

- Five companies—which represent 20%, or $70 billion, of the group’s total market value—will emerge from the downturn in a position of financial strength. We define strength as having a five-year ROIC that is above the segment median, coupled with low leverage (meaning a total debt to EBITDA ratio of less than 4.5).

- On balance, investors are valuing midstream companies fairly, which limits the number of potential opportunistic acquisitions. (See Exhibit 3.) Our analysis confirms that, even in the face of substantial share price volatility, the predictive value of the relationship between a company’s market capitalization and three-year EPS performance holds.

Based on these findings, we conclude that most midstream companies should act in the short and medium terms to enhance their postcrisis prospects—whether it be to shore up finances or, at the other end of the spectrum, leverage an already strong base to enable greater growth.

A COMPANY-SPECIFIC PATH FORWARD

The best way forward for a company will depend on where it sits on the spectrum of returns and financial strength.

Companies in Weakened Financial Positions

Companies in a relatively weaker financial condition should focus on business transformation aimed at reducing costs, improving capital efficiency, and releasing cash for future growth investments. Businesses in this group consist of two types of players: large firms (including three of the five largest midstream companies) and smaller, more niche-oriented players.

Both groups find themselves in a challenged position due to a legacy of debt-fueled investment and exposure to underperforming segments of the market, such as dry natural gas plays, Canadian oil sands, and NGLs. Absent appropriate efforts at transformation, the companies’ growth efforts will continue to be handcuffed by their high debt burdens.

Companies in this group should emphasize cost optimization, and some have already announced cost-reduction efforts targeting both capital expenditures (budgets across the segment have already been slashed by as much as half) and operating expenditures. Most players will need to do even more. We recommend they aim for a comprehensive transformation of their finances through a combination of levers:

- Zero-Based Budgeting (ZBB). This is geared toward the generation of both short- and long-term savings through bottom-up budgeting and clear cost accountabilities. In our experience, ZBB can help a company realize a reduction in sales, general, and administrative costs of up to 30%, driven by the rightsizing of the organization to current activity levels, reduced complexity, and the establishment of a cost-conscious and an owner-operator mindset among managers.

- Utilization of Digital Technologies. Midstream players can often generate substantial value by deploying digital technologies, particularly in operations-focused applications. Companies should establish an overarching digital strategy, if they do not already have one. This would help them identify specific applications—terminal operations and predictive maintenance, for example—where the use of these technologies can be profitably piloted, deployed, and scaled.

- The Pursuit of Operational Excellence. The best operational-excellence programs have common characteristics. They span the entire business, are driven by the top, establish cost-category owners, and address cultural change in addition to operational improvement. Such programs can deliver significant value, including a reduction in maintenance costs of up to 30% through improvements in value-based maintenance, planning, and execution. They can deliver up to 40% improvement in a technician’s effectiveness through advanced efforts to maximize tool-use productivity.

- Enhancements to the Management of Capital Projects. Excellence in capital project management can be fostered through deliberate and focused collaboration with contractors, transparent risk assessments and critical-path analyses of project plans, and the institution of new processes and change management programs to optimize project team behaviors.

Companies in particularly dire straits, whose short-term debt poses an immediate threat to their solvency, should focus solely on ensuring the availability of enough cash for survival. These players will benefit from establishing a plan to quickly free liquidity—potentially through such measures as asset sales, contract renegotiations, and wage freezes—supported by proper controls. We recommend the establishment of a governance office that monitors and forecasts cash generation, confirms the impact of proposed actions, and rigorously monitors how cash is released and utilized.

Companies in Strong Financial Positions

Companies in positions of strength, by contrast, should seek to exploit their positions by identifying and seizing growth opportunities, aiming to build a portfolio that is both strong and resilient. Two of the five companies in this group are large players (with valuations exceeding $10 billion). These companies have put themselves in winning positions largely through a history of patient investment in growth, along with a consistent focus on debt management.

While scenario planning in response to market uncertainty isn’t new, a more robust process is called for in today’s increasingly uncertain world.

These players should first look to build a more resilient portfolio through strong scenario planning. While scenario planning in response to market uncertainty isn’t new, a more robust process is called for in today’s increasingly uncertain world. Traditionally, companies would plan for a specific, likely scenario, but now, they must create a strategy that has the potential to yield high levels of success and resiliency across a range of scenarios. This takes going beyond the obvious. Scenario planning has typically rested heavily on consensus views and projections based on publicly available information. In the present environment, companies must consider disruptive developments, such as new or emerging technologies, and the potential for wildcard events, such as fracking bans or future pandemics.

Financially strong companies should also ensure that their portfolios are sufficiently diversified by asset and commodity type, as well as by geography. Greater diversification, in cases where a company deems it necessary, carries some risk, but it also offers potential benefits, especially when newly acquired assets are outside the buyer’s industry and are acquired during times of economic weakness. Our analysis indicates that noncore acquisitions in weak economies create about 4 percentage points more value than core acquisitions do in such periods, as they can help companies’ smooth earnings volatility and, when incorporated into a diversified portfolio of midstream assets, provide more strategic options.

Further, financially healthy midstream players could drive growth through M&A. This can be highly rewarding, particularly in today’s economy; we have found that M&A transactions carried out during downturns typically outperform strong-economy deals by about 10 percentage points. As noted, the market is currently valuing most midstream businesses accurately, resulting in a limited number of obvious acquisition targets. Nevertheless, healthy companies should still consider acquisition as a strategy. But their M&A teams need to be more targeted in their acquisition screening, more deliberate in their estimates for revenue and cost synergies, and more efficient in their overall approach.

Financially healthy midstream players could drive growth through M&A.

First, M&A teams need to think carefully about what they are looking for in a potential target. With fewer obvious targets available, screening efforts ought to extend beyond entire companies to assets or a portfolio of assets that can help meet broader strategic objectives. Second, acquisitive midstream businesses should be methodical and realistic when determining the synergies they hope to realize. Cost synergies announced from recent M&A activity in the utility space range from 1% to 4% of total acquisition cost; those from oil and gas range from 1% to 5%. By contrast, announced cost synergies in the midstream segment range from only 1% to 2%, approximately. Moreover, the challenge of realizing synergies from asset-focused acquisition in this space is especially challenging in the current environment, since it can be difficult for acquirers to access detailed information on individual assets. The lack of transparency also increases the odds that acquirers are paying full or nearly full value (or overpaying) for assets, leaving little to no margin for error.

Finally, midstream players that are contemplating acquisitions need to be more efficient with their overall M&A process, including its speed. Deals undertaken in weak economies take roughly 20% longer to execute than those in strong economies, stemming from the greater challenge of performing due diligence and accurately determining valuations, as well as the increased difficulty in securing financing. The extra time can lower the return on investment.

As the dust settles and midstream companies look ahead, they need to make a realistic assessment of where they are and where they hope to be in the next two to five years. Then, to reach their target state, they need to design a viable plan—one that can be successfully executed amid ongoing market turbulence—and bring it to fruition.