Since 2016, the US generic-drug industry has been experiencing real challenges to value creation. US generic-drug prices are eroding rapidly, new challengers are accessing the market with low-price products, and pharmacies are joining forces with wholesalers to leverage purchasing power. Meanwhile, the ongoing inquiries into pricing and opioid marketing have created uncertainty and adversely affected several companies’ valuations.

Although the industry has recently begun to stabilize, US generic-drug companies will not thrive if they continue to employ their momentum strategies. Going forward, the following strategies offer competitive advantage: consistently being first-to-file (FTF) and first-to-market (FTM), especially with Paragraph IV (PIV) certification products; engaging in the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) business; excelling at complex generics; and consolidating to achieve advantage economics.

These strategies, however, are available only to companies with a natural advantage, and they won’t solve the growth and profitability challenges of companies with significant exposure to commodity portfolios. The hope for these companies is to move away from a reliance on generics and to focus on higher-value, differentiated products.

The hope for these companies is to move away from a reliance on generics and to focus on higher-value, differentiated products.

The Current State of US Generics

The US generics industry comprises two distinct business models: manufacturing and supplying older and commodity generics and competing to be FTF-FTM in the race for new generic-drug launches.

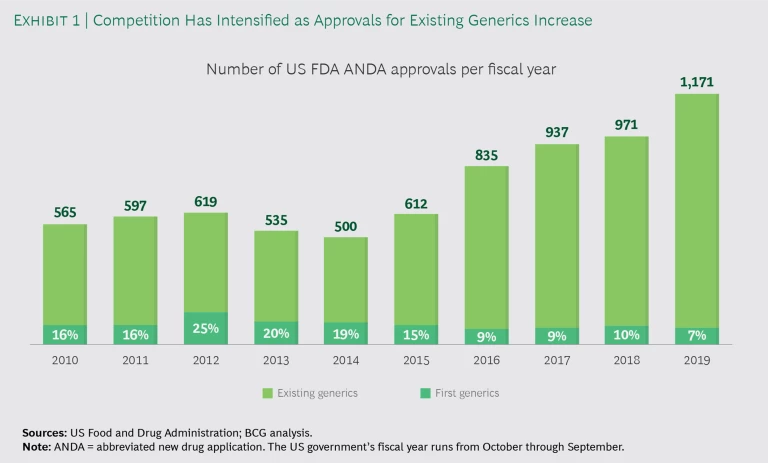

Over the years, established US generics companies have built up increasingly large portfolios of old generic products, and a number of Indian entrants have added to the offering. Since 2016 in the US, under Generic Drug User Fee Amendments, or GDUFA, I and II, the number of abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) approvals has increased considerably, but more than 90% of the approvals have been for established products for which other ANDAs already existed. (See Exhibit 1.) As a result, mature generics are hotly contested, and most become commodities within two to three years of launch.

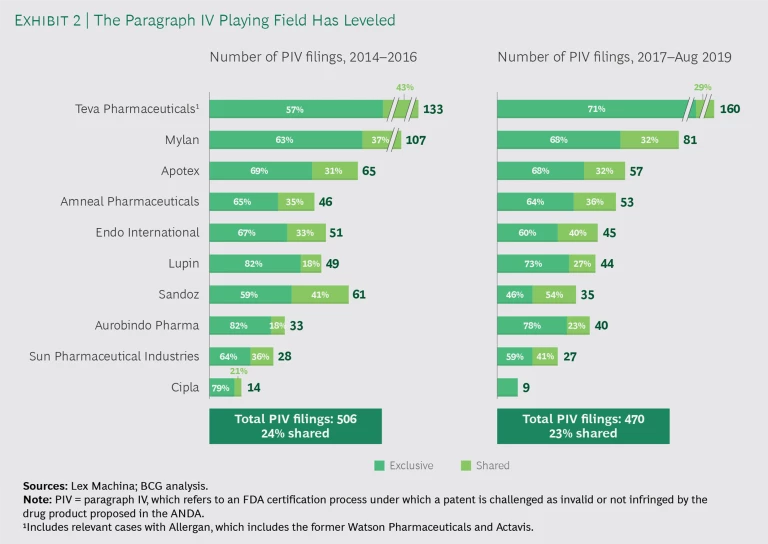

On the other hand, FTF-FTM products can still be very profitable for the duration of exclusivity. The number of companies with the necessary capabilities—including navigating PIV filing and litigation—is still limited, but it has grown as certain Indian companies have become more sophisticated. (See Exhibit 2.)

With strong competition among manufacturers and excess capacity in manufacturing and R&D, US buyers are exploiting their advantage. Three buying consortia, which represent 90% of the US market, are positioned to drive down suppliers’ prices and to extract large discounts on all inputs, including new generics. This power dynamic is driven mainly by the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs).

While PBMs have struggled to control the cost of branded and patent-protected drugs, which represent most of the US payers’ spending on drugs, they have found a soft target in the generics segment and have realized that simple moves to exploit competition can reduce generic-drug prices and generate big savings. Pressure from channel buyers helps them in the short term but hurts them in the long run. Market rules are such that retail prices end up depressed, and the overall value pool declines for everyone. Wholesalers, in particular, are feeling the pain.

As a result of these market forces, large Western generics companies are suffering. Teva Pharmaceuticals and Mylan are still successful in the FTF-FTM game, but they are burdened by large commodities portfolios. Companies that are not entirely focused on generics, such as Novartis (with its Sandoz division) and Pfizer (with its Upjohn division), have begun to scale down through divestitures or carve-outs.

The larger Indian generics companies are doing slightly better owing to their lower cost base and comparatively younger portfolio. But the smaller Indian players that spent years seeking approval for commodity products are realizing that they are now ten years late to market, and the payoff won’t justify the initial investment. However, since all past investments are “sunk costs,” these companies will continue to exploit their existing pipelines, adding even more pain to the marketplace as supply exceeds demand.

Several US domestic generics players are also struggling, particularly those that avoided the consolidation trend and grew on the basis of a narrow portfolio of generics. Many of these businesses have plateaued—or worse, rapidly declined—especially those dealing in opioids. They have struggled to rebound because their R&D capabilities are limited and rebuilding a broader generics pipeline is a ten-year undertaking.

Future Sources of Value

The commodity generics segment, including the Indian companies, will continue to struggle for the foreseeable future. Large global generics companies with broad portfolios used to enjoy a supplier advantage, but US buyers now have so many options among scale suppliers that breadth is no longer an asset. On a full-cost, or ROI, basis, it’s likely that more than 50% of each company’s products are unprofitable. As a result, these companies will undoubtedly rationalize their portfolios and manufacturing capacity in the hope of increasing prices. However, manufacturing assets are often depreciated, products still generate positive cash margins, and rationalizing a manufacturing network takes time and money. It will, therefore, be several years before the generics supply in the US is in balance with demand.

Where, then, are pockets of value in US generics?

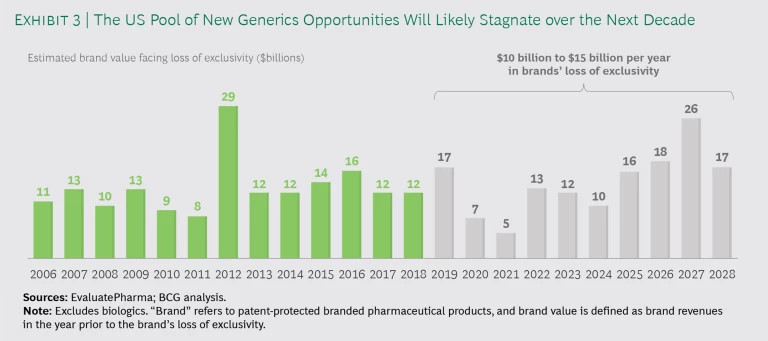

First-to-File and First-to-Market. FTF-FTM products still generate major returns for generics companies, and we believe that they will continue to do well. The FTF-FTM market has become more competitive in recent years as a number of Indian companies have improved their PIV challenges and FTM capabilities, but only a handful of companies really have the R&D capabilities at scale and the acumen to play the game well. The incoming volume of small-molecule generics opportunities is not as large as in the past, but it remains sizable and stable. (See Exhibit 3.) FTF-FTM will remain a good business model for the foreseeable future. Given that it takes more than five years to develop and bring a new generic product to market, the pipeline is already set for the next five to ten years.

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient. The API business is a rare pool of profitability. Margins remain attractive even in the most commoditized categories, because supply is much more concentrated in APIs, and suppliers have achieved greater scale by operating globally rather than regionally. At the formation of a market for a generic drug, once a few API suppliers have received approvals from the FDA and European Medicines Agency, there are very limited incentives for new entrants to compete. Even Chinese API manufacturers—the new challengers in global markets—think twice before investing to obtain FDA approval since it’s likely that they will become mired in a US price fight and will win share only by undercutting established market prices, hurting incumbents’ and their own margins.

That said, there is a rationale for established API manufacturers to enter the finished-dose business, especially if they have a large share of the API business and their finished-dose manufacturing assets are specialized on, for example, antibiotic, cytotoxic, or hormonal products. Over the long term, we expect the market to organize around a small number of backward- or, more likely, forward-integrated API players that specialize in a certain type of chemistry.

Complex Generics. Products requiring specific technologies, such as extended-release formulations, respiratory and inhalation devices, and sterile products (for example, ophthalmic solutions), face less competition than simple generics. However, in complex generics markets, offering a product early is essential for capturing value. The market dynamics for these products will likely be similar to those for simpler oral solid-dose products, with little difference from the payers’ perspectives as long as the products have FDA approval with an AB rating. With a buying approach that is similar to the one they use for oral solid-dose products, channel buyers will make purchase decisions and substitute on the basis of their own economics.

In complex generics markets, offering a product early is essential for capturing value.

Given the higher upfront investment required for complex generics, it is crucial to have the necessary R&D and manufacturing capabilities in place (internally or externally) to support early market access.

Consolidation to Achieve Advantaged Economics. To date, consolidation efforts in the generics sector have not generated much value overall, and we don’t believe that general consolidation will generate value under the current market conditions.

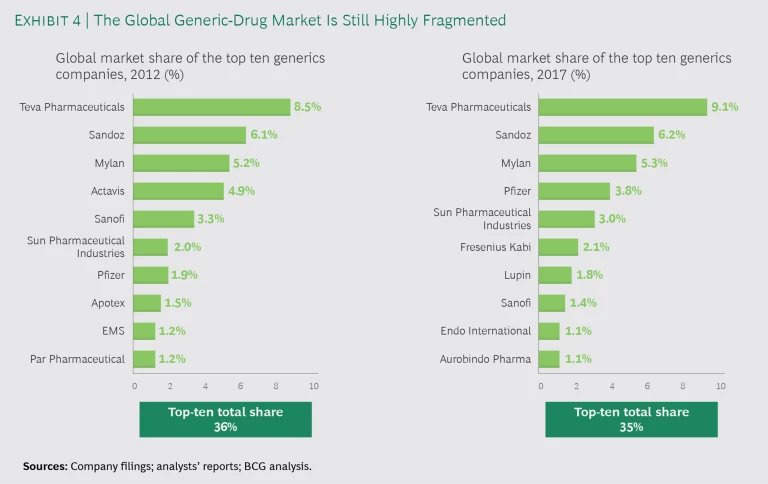

In the US, size per se does not confer an advantage, because buyers can shift market share to counterbalance suppliers with a material market share. As a result, the top ten generics companies in 2012 had market share of 36% and a new set of top-ten generics companies still controlled only 35% of the market in 2017. (See Exhibit 4.)

On the other hand, companies have opportunities to create value from consolidation in niches. For example, they can drive backward or forward integration around certain APIs to create scale, and they can do the same in markets outside the US where local sales forces drive the go-to-market model for branded generics (sold with a company umbrella brand or distinct product brand).

Companies have opportunities to create value from consolidation in niches.

Expansion into Differentiated Products. Companies with significant reliance on commodities will need to expand beyond generics and focus on higher-value, differentiated products, such as incremental innovations covered by 505(b)(2) of the US Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; biosimilars; and, potentially, molecular innovations.

Although these may seem natural extensions of the generics business model, they are segments that need to be addressed with open eyes. In the US, barriers to the uptake of biosimilar drugs are still high. Incremental innovation around the molecules—for example, alternative dosage forms—is a space that large pharma companies have consciously deprioritized over time because they believed that they could achieve a bigger bang for their money by betting on breakthrough therapies.

There are certainly smaller opportunities that generics players can tackle. However, the core competencies required for innovation—even incremental—are different from those needed to be a successful generics company. Drug innovation is more about medicine than engineering, which requires new capabilities, and successful products must bring meaningful value to patients. In concept, a shift to a more differentiated and innovative portfolio is certainly an attractive strategic option for a generics company, but it requires a profound transformation of the company’s business model, not just an extension.

The US generics industry is undergoing a major transition. By embracing a strategy that capitalizes on the high-impact pockets of opportunity, generics companies can secure a path to profitable growth. However, there are no simple solutions: true solutions will require material, multiyear efforts.