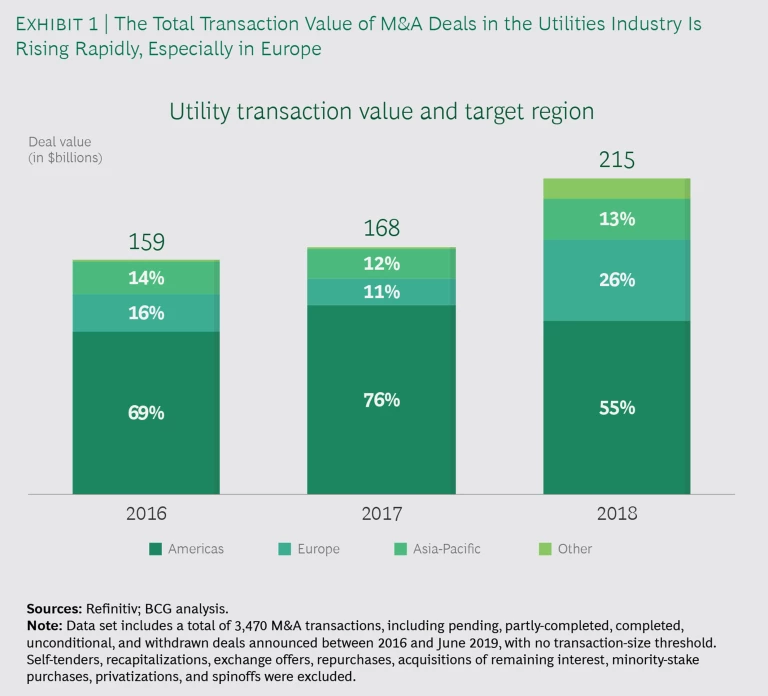

The global utilities industry is on an M&A binge. In 2018 alone, the industry carried out over 1,200 M&A deals worth more than $215 billion, most of them in Europe and North America. Despite their proliferation, these deals are not translating into success.

Total returns for shareholders in companies that have completed M&A deals recently have lagged far behind the industry’s average as a whole. In some cases, utilities have paid too much for the companies they bought, but our experience with clients suggests that poor post-merger integration (PMI) is to blame for the lackluster results.

To improve their performance, utilities must plan from the outset of a deal how to carry out and govern the integration process, develop strategies for capturing the anticipated synergies, and carefully design the outlines of the combined organization—all while accounting for their unique regulatory and multi-stakeholder environment.

Getting these elements right will become more important should the COVID-19 pandemic now threatening the global economy trigger increased M&A activity. Our research shows that M&A transactions carried out during weak economic periods generally produce better returns for shareholders. Even so, no company can afford to neglect PMI if it hopes to get the most out of its M&A deals.

No company can afford to neglect PMI if it hopes to get the most out of its M&A deals.

In what follows, we analyze the current state of M&A activity in the utilities sector, examine the reasons why utilities struggle to integrate the companies they buy, and suggest how they can power up their efforts to grow through M&A.

The Case for M&A

As utility customers everywhere increase their efficiency and turn to alternative power sources, energy sales are stagnating, especially in the US and Europe. For utilities, this means slim margins and reduced profitability.

Energy intensity, an indicator of an economy’s overall level of energy efficiency, has been on the decline (the lower the intensity, the higher the efficiency) over the past ten years in every G20-member country, and is expected to continue falling. Regional legislation, such as the EU’s 2012 Energy Efficiency Directive, is only accelerating this trend; the Eurozone’s energy intensity decreased by 37% between 1990 and 2017. China, which accounts for more than a fifth of worldwide energy demand, is also dramatically improving its energy efficiency, dampening global demand further.

In short, utility companies’ efforts to grow the top line organically will likely remain a challenge for the foreseeable future. Meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement—to keep global temperatures from rising 2°C by reducing energy-related CO2 emissions—will lead to even greater dependence on renewables and further disrupt operations across the industry in coming years. The energy transition will require business model innovation and technological expertise that often cannot be found in-house, putting increased pressure on utilities to look elsewhere for the capabilities they will need.

Taken together, these factors have given utilities little choice but to turn to M&A for growth. In 2018, the industry engaged in more than 1,200 M&A transactions, generating $215 billion in deal value, or approximately 7% of the year’s global total of over $3 trillion. More than 80% of these deals involve North American and European target companies. Exhibit 1 reveals that the share of European targets is growing particularly fast, up from 16% of all deals in 2016, to 26% in 2018, due in part to increasing interest among Chinese investors. Demand for investments in renewable power generation is also on the rise.

To date, leading players have announced plans to allocate at least an additional $300 billion in capital spending for new investments and M&A transactions—$180 billion in Europe, $100 billion in North America, and a minimum of $20 billion in Asia-Pacific. Companies have already included more than 100 deals into their capital spending plans for the next four years, the majority of which will likely be acquisitions or other investment programs. In the US, for example, Dominion Virginia Power announced investments of around $4 billion, primarily for renewables.

The $300 billion figure is a bare minimum. Although Chinese companies do not disclose exact figures for their investments, the China Three Gorges Corporation has announced further plans to invest in Europe and Latin America. This case, together with other opportunistic deals not included in the estimate, suggests that the actual amount of capital spending will be much higher in the future. And if recent experience is any indication, these transactions constitute only a drop in the bucket of what’s to come. Many utilities have the requisite cash, and some of the largest deals are never announced beforehand.

Furthermore, while the long-term economic impact of the pandemic remains uncertain, it has already had a negative effect on the utility industry. Spot prices for oil and gas have dropped sharply, and so has the spot market for power. As a result, many utilities, especially those focusing on power generation, will suffer. While it is impossible to tell how long the impact will last, distressed utilities may become prime targets for others with healthier balance sheets.

The Strategic Rationale

Most recent M&A deals have been carried out by strategic buyers looking to acquire rivals and companies in other markets. It is worth noting that the number of financial investors has also been growing in recent years; in 2018, they accounted for 27% of deals, up from just 19% two years earlier. A large proportion of utilities consists of regulated businesses that offer consistent, stable returns, making them especially attractive to private equity and pension funds.

In general, strategic M&A activities center on three goals, in addition to growth:

- Scale. Incumbents in geographies with high fixed costs are scaling up their operations by purchasing rivals or expanding their footprints. At the same time, they are looking at adjacent energy sectors to gain efficiencies and help facilitate the energy transition away from fossil fuels.

- Focus. Companies in the energy and utility sectors are among the most vertically integrated of any industry. Likely, utilities will not benefit from this structure as their industry grows more complex and flexibility becomes increasingly important. Already, many utilities are looking to streamline their portfolios in order to specialize in aspects of the energy value chain, such as distribution and transmission, sales, and service. Divestments and transactions that involve asset swaps enable utilities to concentrate on their strengths and aim for operational excellence.

- Capabilities. The pursuit of a green future and the ongoing energy transition demand innovation and the willingness to adapt to technological change. When it comes to developing the technologies and capabilities needed to keep up, smaller companies are often faster and better positioned. For large utilities, which often struggle to move quickly in fast-paced environments, it is more effective to acquire these capabilities than to build them on their own.

Diminishing Returns

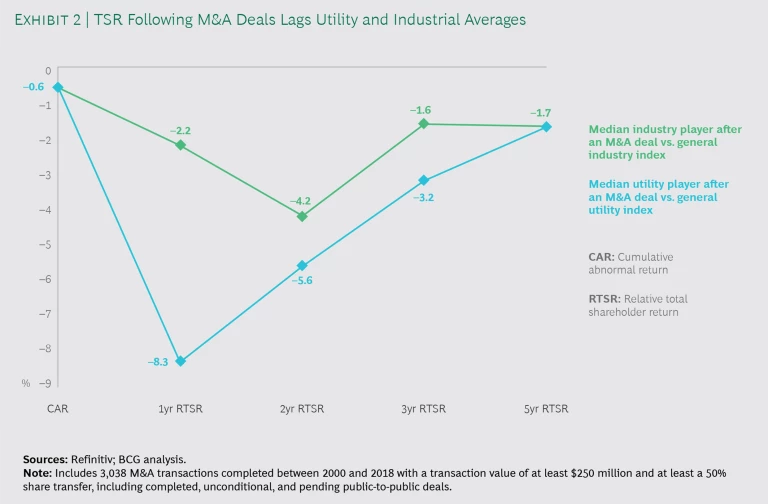

Thus far, utility companies’ ambitious efforts to promote growth and create value through strategic M&A deals have failed to produce the gains that company leaders—and shareholders—had hoped for. We analyzed more than 3,000 transactions between 2000 and 2018, calculating their total shareholder returns (TSR) across the five-year period following each deal. The results were unimpressive.

As Exhibit 2 shows, utilities’ cumulative abnormal returns (CAR)—returns above or below the sector norm, triggered by “abnormal” events such as mergers, dividend announcements, and lawsuits—fall an average of 0.6% immediately after the announcement of an M&A transaction. This is in line with the CAR of companies announcing deals in other industries, indicating that like other shareholders, utilities investors are often skeptical of the strategic rationale behind many M&A transactions and worry that they will not produce the expected synergies.

After that, however, the results for utilities engaged in M&A diverge significantly. In the first year following the completion of some type of M&A deal, utility companies yielded an average of 8.3% less in relative total shareholder returns (RTSR) compared to the industry average. Their results slowly improved after the first year, but even after five years, they still lagged their industry peers by 1.7%.

Even more troubling is the fact that utility companies significantly underperform the average of all industrial companies engaged in M&A. It is well known that shareholder returns tend to fall in the first few years after an M&A deal. But the 8.3% decline in utilities’ TSR in the first year after a deal closed is a full 6.1 percentage points lower than the average among companies in all sectors. Not until the fifth year did the TSR of utility companies improve enough to catch up. Clearly, the initial doubts about the strategic advisability of many of these deals have turned out to be well-founded.

There are no clear-cut explanations for utilities’ poor performance, though one explanation may be that overpaying for acquisitions can make it far more difficult to achieve the expected financial results. There is considerable evidence that many utilities have indeed overpaid for the assets they buy, particularly in Europe in the first decade of the 21st century, when high gas prices and utility rates provided companies with extra cash.

But the most likely cause for the sub-par returns is poor post-merger integration (PMI). Speed is of the essence in PMI, and utility companies are far slower than others—by an average of 81 days—to close on the deals they announce. If companies can’t speed up their efforts to integrate the assets they buy and achieve the hoped-for synergies, then creating the expected value will likely also be delayed.

The Path Forward

While the reasons for poor post-merger performance vary, in our experience, the specific difficulties utilities face in integration fall into three areas. They struggle to align their PMI efforts with the goals of the M&A deal; they lack a clear plan for capturing the full value of the deal; and they neglect to define in detail the nature and structure of the newly combined organization.

Utilities determined to spur growth through M&A would be wise to build their PMI capabilities in all three areas.

The very first task of any PMI involves choosing the integration lead and putting together the integration management office.

Setting the Direction. The very first task of any PMI involves choosing the integration lead and putting together the integration management office (IMO). The integration lead should be a board member or high-level executive who is fully committed—and has the board’s full trust—to carry out the integration program. The board must discuss any decisions that may affect the process with the lead and be willing to communicate its unwavering support for the position with all internal and external stakeholders. Conversely, the leader must be able to manage the program tightly, adhere to defined procedures and schedules, and defend his or her actions to the board, if necessary.

To manage the project successfully, the integration leader must staff the IMO with people who have the skills needed to make value-generating decisions under often uncertain conditions, and who can build and steer effective teams. Including members of the team behind the integration’s initial design will ensure a high level of accountability for the program’s success.

The program itself should be structured to pull the value-creation levers designed to generate the benefits of the merger—ideally reflecting how the target company will be run once it is fully integrated. To that end, the IMO’s task includes outlining the target operating model, defining the expected synergies, appointing the clean team, determining how IT and HR are to be implemented, and managing the cultural transformation. The team must be able to determine and deliver the calendar of decision steps that drives the execution of the integration program and be willing to adjust it as necessary.

In short, the IMO should become the integration lead’s navigation bridge, empowered to drive the program transparently and with full accountability for the results.

Capturing the Value. Capturing the full value of an M&A transaction is a masterful skill, and the key task of the integration lead. Three critical factors must be taken into account to accomplish this feat:

-

The technical implementation plan lays out a map of the target company structure, starting from its current state. Drawn up properly, the plan sets out the optimal disposition of all assets and people involved in the transaction, with due consideration for the current tax environment. Experts in corporate law and tax matters will be needed to ensure all the targets’ assets are correctly valued, and to account for any hidden reserves, intellectual property claims, or change-of-control clauses that could affect the process. Teams from accounting, corporate control, finance, and HR must work together to assess the plan’s completeness and viability.

The IMO must then determine the implementation steps themselves, so they can be completed efficiently and managed through a carefully structured process. It is essential that the IMO maintains centralized control over the planning stage, given that responsibility for the implementation plan is too often allowed to diffuse throughout the organization—or worse, is neglected entirely.

- Synergies are the most important lever for capturing value from a merger or an acquisition—but are notoriously difficult to bring to fruition. The IMO needs to be fully dedicated to identifying the key synergy opportunities—both in terms of growth and cost savings—early in the program, and then ready to pursue them rigorously until they materialize in the P&L statement. During this pursuit, it is critical to establish business cases for every activity that might produce value. Even business units and pet projects led by powerful executives must be examined carefully to ensure they will continue to add to the value equation.

-

HR implementation is all too often overlooked or deprioritized in the PMI process. But neglecting people issues can be disastrous. Successful HR implementation is based on solid analysis and regular communication. Company leaders need to explain to employees, in straightforward terms, the nature of the current organization, what the target organization will look like, and the path to getting there. This should include real numbers on current and future employment and how employees’ roles may change. Company leadership should therefore involve employee representatives in communicating the PMI plan in the effort to reassure and motivate employees whose livelihoods depend on their jobs.

The IT function and clean teams, too, have a major role to play in PMI. Integrating IT systems and resolving compatibility and data-availability issues is a daunting task under any circumstance, and even more so when bringing together two separate companies. Clean teams must understand the needs of the PMI program and exercise their regulatory leeway to provide insightful analysis of the target company’s operations and practices. Both the IT and clean teams will facilitate value capture only when they interact closely with the overall PMI program and align their activities with the program’s technical, synergy-based, and HR requirements.

Building the Organization. In determining the nature and structure of the newly merged organization, the need for speed must be balanced with the care required to maximize value. Taking some time to pick and choose corporate functions and processes from the best of both companies can be valuable, but it is likely to be more time consuming—and far more expensive—than deciding early to simply integrate the target company’s operations into the acquirer’s. The strategy of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” often works best.

In either case, investing senior leadership’s time in strategic discussions on the high-level target operating model will pay off in the long run. Determining clear top-down design principles early in the PMI process will save time by ensuring alignment among functions and business units. Once leadership has weighed in, it’s time for the IMO to sort out the details, leveraging the knowledge of current employees and securing their buy-in for the coming changes.

Selecting the right set of top executives for the new organization’s various units and functions is essential for building the best possible leadership team. New leaders should be selected early in the process so they have time to build their teams, and they should come from both the buyer and the target company to encourage cross-breeding of new ideas and loyalties. Clear and reasonably attractive options for those who are not chosen will avoid insecurity and foster a collaborative culture.

Every successful company is driven by purpose and culture—the “why” and “how” of organizational excellence—and companies undergoing a PMI must actively work to articulate, adapt, and maintain these core elements. Top leaders often assume that their company’s culture is like that of the company they are merging with, but as always, the devil is in the details. Thorough assessments often reveal dramatic differences between the two—such as why a particular strategy is in place, how performance is evaluated, or even how meetings are conducted. Addressing these differences openly, consciously defining a new purpose and target culture, and communicating the path to the newly structured organization are essential steps for avoiding costly misunderstandings.

Consciously defining a new purpose and target culture, and communicating the path to the newly structured organization, are essential steps for avoiding costly misunderstandings.

Solving the Synergy Equation

Utilities are turning to M&A in their quest for growth and greater returns for shareholders, which makes sense, given the challenges of organic growth amid declining energy consumption in Europe and the US. The unfolding COVID-19 crisis and falling fuel prices may trigger even greater M&A activity if price premiums for target companies fall in a weakening global economy.

But unless utilities can improve their efforts to integrate the companies they buy or merge with, inorganic growth, too, will remain a challenge. Put simply, many utilities lack the capabilities needed to make sure they capture the full value of the prices paid for the companies they buy.

Our experience in helping large utilities integrate purchased companies suggests that the key to success in PMI lies in appointing the right leader and the right team for the job. The PMI team must develop a carefully considered integration plan and rigorously manage its execution, building an organization that can generate the synergies required to capture the full value of the deal.

For utilities that can carry out their post-merger integration in an efficient, organized, and transparent way, the path to growth will be considerably smoother.