Transitions toward the use of low-carbon sources of energy are changing the way the world produces and consumes energy in fundamental ways. In response to growing calls for action, several international oil companies (IOCs) have redefined their businesses in recent years and expanded into alternative-energy areas. National oil companies (NOCs), IOCs’ fully or partially state-owned counterparts, are also under pressure to review their strategies and define their path ahead in the emerging landscape. But their purpose differs from that of IOCs, and they face different challenges as well.

By growing their businesses, IOCs create value for public shareholders. NOCs’ central role, however, is to monetize national hydrocarbon resources as effectively as possible in order to maximize state revenues while guaranteeing a secure supply of affordable energy for the nation’s needs. But like IOCs, they must respond to societal pressures at home and abroad and adapt meaningfully to energy transitions. The task they face is how best to do all that in the most environmentally sustainable way.

All NOCs will have to significantly reduce emissions and lower production costs to stay competitive and help mitigate climate change.

NOCs that operate in geographies with abundant, readily available reserves of lighter oil have a head start when it comes to producing hydrocarbons cheaply, efficiently, and with the lowest possible emissions. But all NOCs will have to significantly reduce their emissions while lowering production costs in order to remain competitive and play their part in mitigating climate change. They will need to develop new carbon abatement technologies, streamline their organizations, and prioritize low-cost production.

The Importance of NOCs

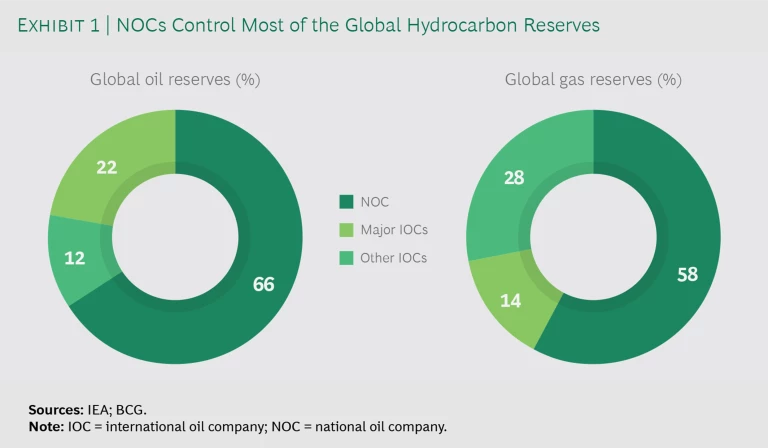

NOCs are major players in the global oil and gas sector. Together, they control more than 65% of global crude oil reserves and more than 55% of global gas reserves. (See Exhibit 1.) Some of the world’s biggest hydrocarbon producers are so-called export-focused NOCs, which have large domestic oil and gas resources that they sell in global markets. Import-focused NOCs, on the other hand, depend on resources that they’ve acquired abroad to supplement their domestic production and meet local demand.

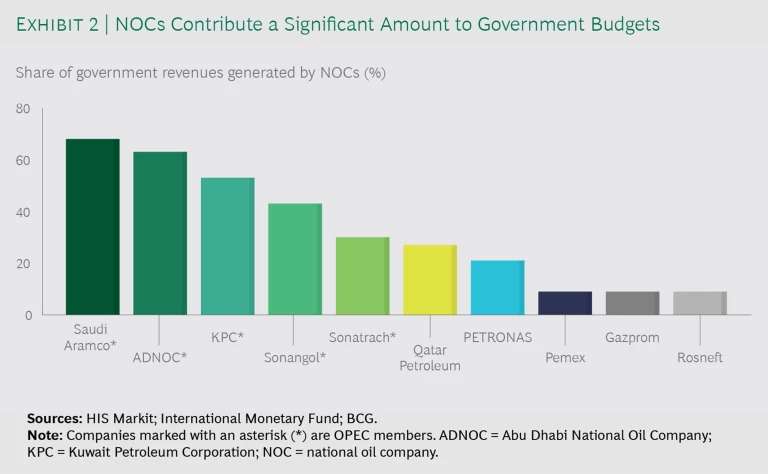

As state-owned organizations, NOCs play a pivotal role in their countries’ political economies. Several OPEC member countries, despite efforts to broaden their economies, still derive more than 60% of their revenues from oil and gas sales generated by their NOCs. (See Exhibit 2.) The proportion is also significant in some non-OPEC countries, including Mexico and Russia, which have far more diversified economies and where the oil and gas sectors contribute a smaller share to their respective countries’ GDPs.

In most countries with NOCs, the revenues produced by those organizations are vital for economic sustainability. They help to finance public infrastructure projects and development and welfare programs. The NOCs themselves play a key role in developing national resources and capabilities and in supporting employment. And global demand for the NOCs’ oil and gas offers a source of international political influence for the governments that own them.

We believe that NOCs can continue to play an important role in the global energy landscape if they tackle their emissions and improve their operational efficiency. Consider, for example, that:

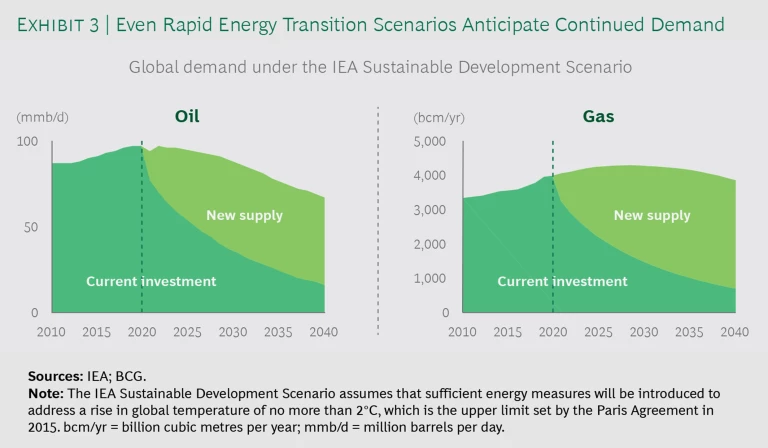

- Even under rapid energy transition projections, such as the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario, demand for hydrocarbons isn’t anticipated to dry up overnight. The scenario indicates that, in 2040, daily demand for crude oil will be 67 million barrels, while the annual demand for natural gas will be 3,854 billion cubic meters. (The estimates for these levels of demand are based on a rise in global temperature of 2°C, which is the upper limit set by the Paris Agreement in 2015. If the increase is less, then the need for fossil fuel resources would also be lower). Given their large oil and gas reserves and national purpose, NOCs have an incentive to capture a big chunk of this volume as long as demand lasts. (See Exhibit 3.)

- In a warming world, NOC-owning governments are rightly responding to their climate change commitments under the Paris agreement by investing in renewables and other low-carbon technologies. Several countries with export-focused NOCs are relying on revenues from oil sales to fund these investments. However, governments will still need to identify the most effective approach for exploiting alternative-energy opportunities. This is likely to include creating new state-owned companies or tapping private-sector expertise, although, in some countries, import-focused NOCs may naturally become alternative-energy players in time. (See “The Renewables Opportunity for Import-Focused NOCs.”)

The Renewables Opportunity for Import-Focused NOCs

Import-focused NOCs may need to rethink their strategic priorities, however. Over the coming decade, competition for cheap, low-carbon oil and gas reserves will become fiercer. As a result, it may make sense for these companies to transform themselves into alternative-energy players.

Given the abundance of such renewable energy sources as solar and wind in some countries, these NOCs may be in a stronger position to provide affordable long-term energy supplies for their nation—a key part of their mandate—by taking this step. At the same time, they would help support government policies designed to curb their country’s emissions.

Much will depend on how technological advances, government policies, and a continued decline in renewable costs will shape domestic demand for alternative energy. What’s more:

- In many countries, COVID-19 is already altering the contours of energy transitions toward low-carbon sources.

- Some countries have introduced green stimulus initiatives with the goal of accelerating innovation and the adoption of wind, solar, and renewable battery technologies, thus reducing the country’s reliance on oil and gas imports.

- In China and South Korea, increasing sales of electric vehicles is a key priority.

In the short term, import-focused NOCs may not be able to become pure alternative-energy companies as long as oil and gas make up a significant share of their home market. Nevertheless, by concentrating on building low-carbon energy businesses, they could mitigate the substantial risks and potentially high costs of developing the overseas hydrocarbon reserves that they are likely to depend on increasingly in the years ahead.

Nevertheless, with their government owners’ finances increasingly challenged by low oil prices, NOCs will have to compete harder for scarce state funds and demonstrate greater capital discipline. But as IOCs are forced by their public shareholders to curb capital spending and diversify their portfolios, the importance of NOCs as oil and gas producers is likely to grow, reinforcing their value as revenue generators for their government shareholders.

Some NOCs Have a Head Start

Faced with the dual pressures of scarce finances and a growing demand for cleaner crude, NOCs need to reduce their emissions, improve their operational efficiency, and lower costs to compete. Some are in a better starting position to deliver on these imperatives than others. While NOCs include some players that depend heavily on foreign capital and expertise to develop oil and gas resources, others are technically and operationally advanced, and well-financed domestically. In broad terms, NOCs differ along the following four dimensions:

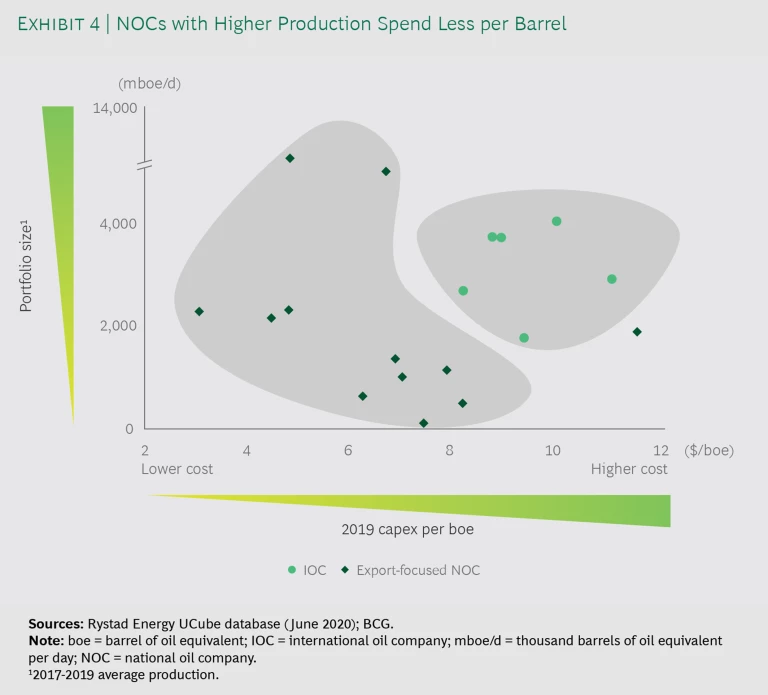

- Resource-Development Costs. Development costs vary widely depending on the size and nature of a company’s oil and gas resources. NOCs with large resources benefit from economies of scale, which help to reduce costs. However, companies that rely on the production of heavy (with a high density) or sour (with a high sulfur content) crude face relatively greater costs to extract and refine the oil so it can be marketed. Because these types of crude require more energy to produce, they also generate greater greenhouse gas emissions per barrel. In the future, as consumer concerns about company emissions and crude’s carbon content increase, NOCs with cleaner and lighter reserves and a smaller carbon footprint are likely to secure buyers more easily. (See Exhibit 4.)

- Institutional Robustness. The ability of NOCs to make decisions quickly and effectively varies significantly. Companies with a more developed institutional capacity for decision making and robustness typically enjoy greater freedom to make their own strategic and capital allocation choices without government intrusion. This can have a major impact on how they respond to disruption.

- Government Financial Strength. Because NOCs depend on funds from their government shareholders, factors such as the strength of state finances can have a direct impact on companies’ strategic options. The funds available to companies for important investments are likely to be more limited, for example, in countries with weak finances, when the state demands a higher dividend from its NOC, and during periods when governments are exercising greater fiscal restraint.

- Operational Efficiency. NOCs with sophisticated technical and operational capabilities—including how they manage upstream exploration and production activities, and how successful they are in curbing costly emissions and leaks from their operations—are able to generate greater profits without increasing cost.

Over the next decade, NOCs with access to abundant low-emission production, robust and agile decision-making processes, a supportive and financially healthy government shareholder, and strong operational efficiency will have a head start over their peers. They will be well placed to be among the cheapest, cleanest, and most efficient operators.

NOCs with access to abundant low-emission production, agile decision-making processes, a healthy government shareholder, and strong operational efficiency will have a head start.

Clearly, some of these factors are outside NOCs’ direct control. A company’s domestic reserves are determined by geology; healthy government finances are shaped by fiscal policies and wider economic drivers; and an NOC’s strategic course is set, or at least influenced, by the state. But all NOCs can improve their competitive potential by taking steps to become cleaner and cheaper producers.

Five Steps to Become Cheaper and Cleaner

A commercial imperative is influencing the move toward becoming cleaner and cheaper producers. Export-focused NOCs will have to do so to sell their products to increasingly environmentally conscious consumers abroad, while import-focused NOCs with large domestic markets will need to follow suit to ensure continued energy security as their governments seek to meet climate goals. Companies should consider taking the following actions:

- Reduce emissions. NOCs can significantly reduce their greenhouse gas footprints by taking a variety of steps along the value chain. These include improving energy efficiency, ending natural-gas flaring, reducing methane leaks, switching to renewable sources for power and biofuels for heat generation, using low-carbon hydrogen in their refining businesses, and applying carbon capture, utilization, and storage to decrease their emissions. Companies should also consider supporting technologies and measures, such as reforestation and green agriculture management techniques, that reduce overall CO2 levels in the atmosphere. While the cost of extracting CO2 directly from the air is prohibitive at present, so-called direct air capture technology could revolutionize global climate change mitigation efforts.

- Prioritize low-cost production. NOCs with a broad mix of oil and gas resources need to focus on developing lower-cost, lower-emission hydrocarbons to deliver the biggest revenues at minimum expense. In the medium term, these NOCs should concentrate investment on maximizing production from existing fields, especially those with low-carbon resources or where oil and gas can be extracted cheaply, rather than exploring for new reserves. Some NOCs will need to forge partnerships with foreign IOCs to tap into capital and the expertise needed to lower production costs in their portfolios.

- Develop new technology. Investing in R&D and establishing strong relationships with emerging-technology providers will help NOCs to both acquire and reduce the costs of technology solutions. These solutions can then be used along the value chain to curb emissions and improve operational efficiency. Oilfield services and equipment (OFSE) suppliers will remain key technology partners as long as they deliver the innovations needed to respond to energy transitions. But NOCs will also need to develop new technologies in-house, particularly if balance sheet pressures prevent OFSE companies from carrying out this role.

- Streamline organizations. Up until now, NOCs have often been tasked by governments with creating employment for the domestic workforce. However, the imperative to lower operational costs and improve efficiency will require companies to introduce new, simpler organizational structures and processes. By taking such actions, companies can reduce their cost base, improve decision making, and increase their agility.

- Improve transparency. NOCs should publicly disclose their emissions data in order to bolster their social license to operate both at home and abroad and to highlight the improvements in emissions that they are making.

The ownership structures of NOCs and the unique role they play in meeting government objectives allow them to focus on producing oil and gas while demand remains strong. But they can’t ignore the climate change imperative. They will need to improve their operational efficiency and achieve the lowest emissions possible in order to compete in the years ahead.