For the past few years, in many parts of the world, a protectionist mindset has been challenging the continuing trend of globalization. This mindset, if it spreads further, could endanger the many benefits of more open international trade —which include allowing multinational supply chains to become more flexible and versatile, giving consumers throughout the world better selection and lower prices, and helping pull hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. Open trade has also facilitated innovation and economic cooperation. The most recent example is the expansion of international e-commerce, which has given smaller businesses and those in developing economies access to global markets.

The current wave of protectionism, which has seen the imposition of new tariffs and other trade restrictions, is slowing down these positive developments. The COVID-19 pandemic represents a further deep shock to global trade. It is prompting a reconfiguration of value chains around the world , as countries look to reduce their reliance on certain foreign suppliers and increase their self-sufficiency in strategic industries, and as firms seek to reduce their dependence on single sources of supply. There is a real risk that these trends may further fuel a damaging spiral of trade restrictions and retaliation.

New research conducted by BCG and HSBC for the Business Twenty (B20) has analyzed a range of scenarios that quantify the collective economic implications of the choice between rising protectionism and liberal trade policy reform.

Conversely, if increasing protectionism prevails around the world, it will impose a persistent drag on GDP growth in a global economy already struggling to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. In a worst-case scenario in which COVID-19 proves to be more difficult than expected to control and contain, an even greater shortfall in growth would result.

The data and analysis also suggest that every country would benefit from the pursuit of open trade, including countries that are currently heading down a protectionist path or seeking to isolate their industries from outside competition. Of course, a global regime oriented toward open and fair trade would still face many challenges. For example, no matter what happens, the world will have to confront the daunting task of enabling economic recovery, including rebuilding sectors and trade routes that have suffered structural damage as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. But in an open economic and trade atmosphere, the global economy would have a head start measuring in the trillions of dollars.

Analyzing Trade and GDP Impact

Economists have debated the risks and merits of free trade since the 18th and 19th centuries, when Adam Smith and David Ricardo debunked the tenets of mercantilism. So when the B20 Trade and Investment Taskforce asked BCG and HSBC to evaluate the costs of protectionism over a five-year time horizon, we looked for a substantive, analytic approach. As a basis for analysis, we used the BCG Global Trade Model, which has been reliable in predicting global merchandise trade flows. (See the sidebar.)

A Methodology for Modeling the Future Impact of Trade Policy

To obtain comparative data, we estimated four realistic scenarios on international merchandise trade flows, determined by aggregating a plausible level of protectionism for every G20 country under each potential future.

For each scenario, we determined an index score ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 represents a fully closed trade environment, based on historical precedent (that is, assuming that all indicators are the most restrictive they have ever been), and 1 a scenario of fully open trade (that is, assuming that all indicators are the least restrictive they have ever been). Each scenario score represents the average of the normalized values of indicators in four index components:

- Tariff Levels. These include US-China bilateral tariffs and global average most-favored nation tariffs.

- Broader Trade-Restrictive Trends. These include antidumping/countervailing duties trade remedies, digital services trade restrictions, and aggregate measurements of trade-restrictive measures, as compiled by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and other organizations.

- Trade-Opening Trends. These include new free trade agreements and increases in trade-facilitating measures, as defined by the WTO and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

- Efficacy of the WTO. This is defined in terms of dispute settlement, trade facilitation, and monitoring of the subsidy programs of WTO members.

The five-year time horizon reflects recognition of the evolutionary nature of trade dynamics: they tend to reinforce themselves over time, becoming more extreme in the direction first chosen.

The first scenario, “open and fair trading” represented the highest plausible level of unfettered fair trade, with an effective WTO making it viable. We also modeled a second scenario called the “incrementally improving trading system,” derived from a less ambitious set of trade-opening policies. It generated small levels of improvement each year. A third scenario—the “baseline” case—amounts to continuing the trade policies of 2020 for five more years. The fourth scenario, “rising protectionism,” assumed continually expanding use of tariffs and other trade barriers.

Then, based on historical and observed relationships between trade policy (more precisely, tariffs, import restrictions, import facilitation, and WTO reform) and trade values, we projected trade in merchandise value (exports only, to avoid double counting) and gross domestic product (GDP) for each G20 country and for the whole group under each scenario. Overall trade value is an indicator of overall prosperity because both imports and exports lead to business activity and employment.

We then estimated the GDP effect of each trade scenario, on the basis of the historical relationship between trade and GDP in each G20 country. Unlike some other metrics for GDP, our GDP formula for trade did not merely reflect countries’ trade balance in a conventional sense. Doing so would have misleadingly favored a high export/import ratio. Instead, we looked at the trade balance defined as “exports minus intermediate imports” because it is important to take into account the economic value of intermediate imports, which are indicators of industrial activity, sustainable employment, prosperity, and an economy’s level of embeddedness in global trade networks.

The most illuminating insights come from a comparison of two extreme scenarios of merchandise trade: a “rising protectionism” future, in which average global tariffs rise, the current tariffs associated with US-China trade tensions remain in place for the medium term, and countries adopt very few new trade-facilitating measures; and an “open and fair trading” future, in which countries support open borders and a rule-based, multilateral system. At first, in both scenarios, trade volume rises in 2021 from its 2020 numbers, as the world economy begins recovering from COVID-19. But in the “rising protectionism” scenario, the value of trade levels off by 2022, and GDP levels off soon after. This creates a vicious cycle, in which diminished business confidence provokes even more protectionist competition, lasting at least through 2025.

The “open and fair trading” scenario has similar momentum, but in the opposite, positive direction, with annual trade and GDP growth continuing through 2025. An effective World Trade Organization (WTO), new trade agreements, tariff reductions, and trade-facilitating measures such as mutual recognition of technical standards and expedited administrative procedures increase market access for companies and enable the growth of international e-commerce. The additional compound growth in trade value (compared to the current baseline) reaches 2 to 2.6 percentage points, followed by further GDP growth of 1.8 to 2.3 percentage points per year.

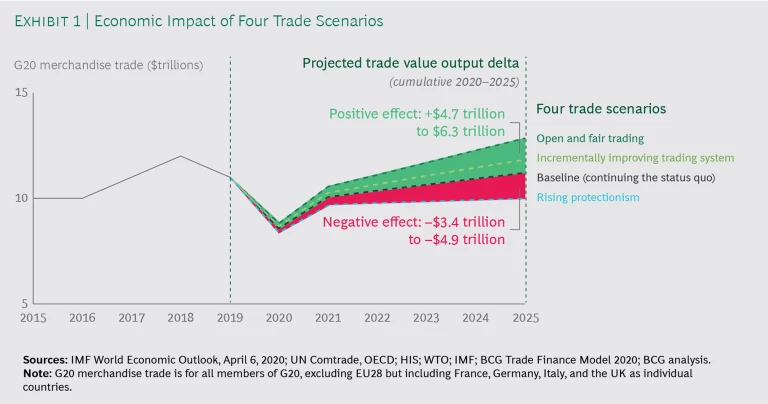

To assess the consequences of choosing a less ambitious set of trade-opening policies, we have also modeled a more modest scenario reflecting incremental improvements in the trading system. This scenario still delivers modest benefits to trade and GDP over the baseline status quo scenario, but with much less momentum for COVID-19 recovery. Exhibit 1 shows all three scenarios, plus a straightforward projection continuing the current baseline status quo.

By 2025, the difference in economic vitality is dramatic. In the “open and fair trading” scenario, the G20 economies would enjoy a five-year cumulative positive material impact in trade value of $4.7 trillion to $6.3 trillion over the baseline projection scenario. (The range depends on the pace of economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.) That is an increase of almost 30% in the global trade value of goods exported, compared to today. In the “rising protectionism” scenario, the G20 countries endure a cumulative five-year lost opportunity in trade value ranging from $3.4 trillion to $4.9 trillion.

It is noteworthy that service industries represent a large portion of GDP, especially in developed markets. If we were to include them in the preceding figures, the value of easing trade restrictiveness would be even more substantial. But trade in services is harder to liberalize because it is challenging to measure and generally subject to national regulation, such as in transportation, telecommunications, and professional services. This explains in part why the global value of trade in goods remains about three times as high as that of trade in services.

The Prospect of Open and Fair Trading

The stated goal of trade protectionism is to protect the economic interests of select domestic industries or companies. But in a world dominated by production along global value chains, trade restrictions may harm the very industries advocating protectionism, as well as hurting end-use consumers.

To be sure, there can be business risks associated with open trade, and some of them have been especially evident during the COVID-19 crisis. Reliance on any single country or source can make private-sector supply chains more brittle. For countries, relying solely on foreign manufacturers for critical supplies (such as personal protective equipment, medical devices, vaccines, or non-pandemic-related supplies such as computer chips or critical materials) can create vulnerability.

But the solution is not to restrict trade. It is to diversify it, developing more flexible, versatile, and therefore resilient supply chains that take into account long-range needs and give every country an opportunity to participate. Fortunately, more and more countries are becoming competitive as manufacturing centers. In addition, emerging production and logistics technologies, such as digital fabrication, provide greater opportunities for diversification and offer trade opportunities for buyers and sellers of intermediary goods.

Business leaders could recommend and advocate several direct measures to move the world toward an open and fair trade scenario. These include the following five:

- Improve international institutions. It is essential to reform and strengthen international bodies, including the WTO, so they can keep pace with the new challenges that businesses face globally.

- Rethink the rules of trade. The world needs a better global trade rulebook and more effective means of enforcement if it is to roll back protectionism, support open markets, and ensure a level playing field globally.

- Foster the growth of e-commerce and digital trade, with technology as a key enabler. The platforms and tools of the digital economy have played a vital role in continuing economic activity during the pandemic-flattening lockdown period. To ensure that digital technology can enable further advances, we need to build a more resilient global infrastructure, establish sound and coherent international rules, and foster digital skills. The importance of digital platforms goes beyond the point of sale. Digitizing the entire trade value chain—from sales to shipping to financing—would materially reduce the time, cost, and complexity of trading across borders, and would give businesses better access to financing and risk mitigation solutions. For this to happen, we need a clear set of universally accepted legal frameworks and standards on digital trade.

- Promote the export of services and nonphysical goods. The crisis has hit many service sectors disproportionately hard, and reviving them will be pivotal in rebooting the global economy. Among developed economies—and a growing number of developing economies—services now account for a majority of GDP growth. Reducing trade restrictions on services can unlock competition and provide incentives for innovation, economies of scale, and opportunities to specialize in service provision.

4 4 For one indicator of how services liberalization might help countries and sectors, see the Services Trade Restrictiveness Index developed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Facilitating trade in nonphysical goods and reducing trade restrictions on digital services or digitally enhanced services are equally important.5 5 Digital services refers to offerings that are fully based on digital technology and on the provision and analysis of digital data (for example, those offered by Google and Facebook). Digitally enhanced services refers to offerings that have complemented or enhanced existing goods and offline services (for example, streaming services and e-books). For a discussion of the transformation of international trade through digitization, see BCG’s “ Global Trade Goes Digital.” A common understanding about intellectual property regulation, common standards regarding data localization, and a fair and rational customs framework for electronic transmissions would help clear the way for rapid progress.

- Promote the positive social and environmental effects of open trade. We must align trade and investment rules to ensure that trade can be a force for good—spurring innovation and inclusive growth, promoting technologies that minimize harmful environmental impacts, and ensuring that international trade does not become a means to avoid societal and environmental responsibilities.

Trust and Collaboration

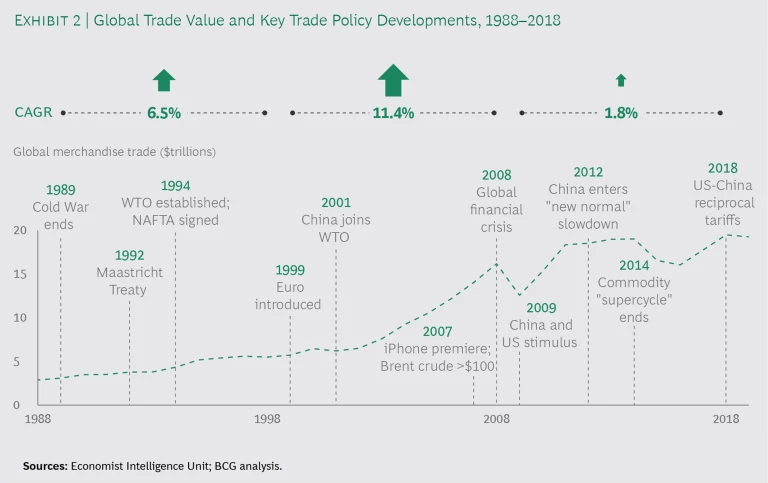

Naturally, an individual country cannot create an open and fair trade policy environment unilaterally. Like vaccination, fair trade requires critical mass to be effective. Indeed, the history of trade growth over the past 30 years suggests that trade growth and trade policy innovation and openness often influence each other, with powerful benefits to overall prosperity. (See Exhibit 2.) That’s why WTO reform is vital, not as a one-off initiative, but as a continuing series of efforts to reestablish the WTO as a credible ongoing arbiter of disputes and a forum for developing and deepening multilateral agreements. Policymakers also need to move beyond focusing on tariffs; they should aim to facilitate trade by reducing nontariff impediments—such as customs costs and delays, paper-based processes, intellectual property rights, and misalignment between standards and regulations—to trade in goods and services. Liberalized trade in services such as logistics services in ports or telecommunications services for e-commerce is an important complement to increased trade in goods, even though it is difficult to measure and regulate. In this context, services liberalization not only is a positive policy in its own right, but also provides useful leverage on trade in merchandise.

In the current geopolitical environment, trust and collaboration among economies must return to their former levels. We believe that even though trade disputes have grown more contentious, many of the differences are manageable, given the political will and a broad consideration of societal interests. Moreover, many examples of international cooperation during the COVID-19 crisis show that it is still possible to collaborate globally toward collectively beneficial results.

The time to start is now. As the world emerges from the worst pandemic and deepest recession in generations, trade openness can be a powerful engine of economic growth and social development. With appropriate policies and international agreements in place, increases in international merchandise trade value—which had reached a historic peak of $18 trillion in 2018 and 2019—should act as a powerful catalyst for faster economic recovery. Business, government, and social enterprise leaders all have reasons to advocate for prosperity, and ample data indicates that the “open and fair trading” future offers the best path to achieving this objective.

This article would not have been possible without the contributions of Nikhil Dangayach, Iacob Koch-Weser, and Stephanie Resch (BCG), and Douglas Lippoldt, Shanella L. Rajanayagam, and Eugen Taso (HSBC).