If your company is to prosper far into the future, it must compete on speed of learning. Artificial intelligence, robotics, and other advanced technologies in the workplace are having a transformative effect on corporate efficiency, productivity, and innovation. But technology alone won’t ensure enduring success. To truly benefit from the latest generation of technological advances, companies must turn themselves into what we call bionic organizations—institutions that can harness both the power of machines and the power of humans.

Too often, companies overlook the human factor. This is a serious mistake. To exploit the full potential of new technology to decode trends and emerging customer needs—and thereby achieve competitive advantage—a company must ensure that its employees are constantly learning, adapting, and acquiring the skills they need to compete in the workplace. As we explained in the first article in this series, that can occur only if the CEO builds a world-class corporate learning capability.

But while many corporate leaders now recognize this necessity, they are less clear about how to develop such a learning capability. In a BCG survey of some of the world’s biggest companies, about 95% of respondents agreed that corporate learning was crucial to the future of the company and should be granted high-priority status. Yet only 15% said they had delivered on this, owing to the difficulty of developing a world-class learning capability. In this article, we will show precisely how CEOs can develop this capability, detailing the framework they should adopt and the steps they should take.

Although 95% of large companies surveyed agree that corporate learning is crucial to their future, only 15% say they have granted it the high-priority status it deserves.

Drawing on our proprietary study of the learning capabilities of more than 120 companies from around the world, we have developed a comprehensive blueprint or framework that identifies the five core components—or domains—of a successful learning ecosystem. To help CEOs develop their approach, we have also crafted a set of questions that they should ask themselves:

- Strategy. Does your company have a clear purpose—a “why”—for learning? Is learning embedded at the heart of your business strategy? And are business needs embedded at the heart of your corporate learning ecosystem?

- Organization. Does your company have a learning culture that the senior executives promote and that fosters a growth mindset in every employee? Does your learning and development function have the operational model, processes, and competencies to support the upskilling and reskilling of your employees across the whole company?

- Offering. How well does your company assess and address individual and collective learning needs? Does your company offer personalized learning journeys for employees to upskill, reskill, and cross-skill, and does it give them the opportunity to attain credentials and other certificates?

- Enablers. Does your company have the necessary infrastructure—the tools and technology—to measure, support, and continuously improve the learning ecosystem? Does your company incentivize employees to learn and business leaders to become tutors or coaches?

- Learnscape Integration. Is your company taking advantage of the entire learning landscape, stretching from individuals and teams to the whole enterprise and to the wider community of learning providers, external networks, and partners?

Along with a blueprint for redesigning corporate learning, we have devised a three-step maturity assessment diagnostic and associated roadmap to help CEOs take the temperature of their organization’s learning capability, benchmark their company against the best learning companies in the world, and introduce a series of strategic interventions designed to transform their company into a learning powerhouse.

A Learning Ecosystem Framework: Does Your Company Have What It Takes to Be a Corporate Learning Powerhouse?

We have closely examined how the world’s leading companies undertake corporate learning. For example, Amazon promotes constant reskilling powered by technology; Google espouses an “always-on” learning mentality; Microsoft practices what CEO Satya Nadella calls a “learn it all” mindset, which he contrasts to an old-style “know it all” mindset; and Toyota advocates lifelong learning.

Yet, for all their individual differences, what distinguishes these companies from most other companies is their focus on learning as something long term, business related, strategic, and constantly evolving. Other companies—insofar as they make any commitment to corporate learning—pursue one-off, short-term upskilling initiatives designed to close a newly identified skills gap. In contrast, the leading companies have built distinctive, sustainable, digitized learning ecosystems.

While their rivals depend on one-off, short-term upskilling initiatives, leaders in corporate education have built distinctive, sustainable, digital learning ecosystems.

Although the world’s best corporate learning ecosystems are unique to the companies that have developed them, they nevertheless have some common characteristics that fit into our framework of five domains and 18 dimensions. (See Exhibit 1.) The five domains are as follows:

- A refined strategy—a clear “why” for learning within the company

- A mature learning organization—a sophisticated learning culture with leadership support and a well-resourced learning function

- A high-quality offering—a first-rate library of content that is delivered through diverse channels

- A set of enablers to support the delivery of learning programs—a robust learning infrastructure with appropriate measurement tools and technology

- Learnscape integration—a network of connections inside the company and outside the company with the wider community of corporate learning and development providers

Each of these domains contains a number of dimensions—critical but more granular components that feature prominently in the world’s best learning organizations. There are 18 dimensions in all. (See the sidebar.) By paying attention to each one, companies can obtain an extremely detailed picture of the strengths and weaknesses of their learning ecosystem.

THE 18 DIMENSIONS OF SUCCESS

Here is the full list of 18 critical dimensions that we have identified:

- Learning Mission. Define a clear “why” for learning.

- Learning Strategy. Ensure that the learning strategy derives from the overall business strategy.

- Learning Culture. Create a vibrant culture that prioritizes learning as critical to personal and corporate growth.

- Business Leaders. Make senior executives and frontline managers day-to-day champions of the learning organization.

- L&D Organization and Operations. Design a cross-functional operating model that supports L&D, and consider making the chief learning officer a C-suite priority.

- Learning Needs. Establish a sophisticated process for identifying current and future skills gaps across the organization.

- Learning Content. Curate a relevant, best-in-class curriculum from a diverse set of learning and development providers to upskill, reskill, and cross-skill teams and individuals.

- Channels and Formats. Deliver learning programs in a wide variety of ways—from online and offline to on-the-job and offsite.

- Pathways and Experiences. Develop personalized learning plans that encompass formal and informal learning for employees to follow throughout their careers.

- Credentials. Build a library of certificates and credentials that give employees public recognition of their learning achievements and offer incentives for further growth and development.

- Technology and Tools. Put in place the right enabling infrastructure to support learning that is instantaneous, on-the-go, interactive, and engaging.

- Workflow Design. Make learning a part of business as usual, by incorporating learning programs into the everyday rhythm of daily work life.

- Measurement and Assessment. Monitor what and how much learning is occurring, using a robust set of tools to effectively, reliably, and consistently gauge employee development.

- Incentives and Accountability. Recognize that learning and development are central to the company’s growth prospects, and structure incentives, benefits, and a bonus system around them.

- Individuals. Put the individual at the heart of the learning ecosystem, and design learning journeys accordingly.

- Teams. Introduce a robust offering of group-based learning activities to foster collaboration and improve team performance.

- Organization. Capture and foster organizational learning with analytics, in a way that increases business-level knowledge throughout the enterprise.

- Community. Forge dynamic connections with customers, clients, universities, and other external stakeholders as part of a proactive effort to give employees access to the best learning and development opportunities available.

A Three-Step Learning-Maturity Assessment Diagnostic and Roadmap

Once they have a clear understanding of this learning ecosystem framework, CEOs can begin the process of assessing how their learning capabilities compare to those of their peers and rivals. This means answering the crucial question: “How good is your company at corporate learning?” Their response to this question could determine the fate of their company over the coming years. So, to help them answer it, we have developed a three-step maturity assessment and associated roadmap. It starts with a health check of the company’s corporate learning ecosystem.

Step 1: Check Your Company’s Pulse—How Fit Is Its Learning Capability?

In our view, CEOs should carry out a pulse check to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their company’s learning capability. Doing this involves conducting a company-wide learning ecosystem maturity assessment (LEMA).

CEOs must go beyond simply assessing the company’s L&D function or leadership. After all, if you want an unbiased opinion about the quality of a meal, you don’t ask the cook; you ask the people who ate it. CEOs must assess everything from the learning strategy and the content and delivery channels to the enabling infrastructure and the connections with external learning providers. They must seek the opinions not only of their fellow leaders, but also of leaders and employees from various functions and business units—who ultimately make up the bulk of the learners.

In tandem with these assessments, CEOs should measure the current strength of their company’s learning and development capabilities against a set of KPIs—for example, the cost of learning, the number of employees engaged in learning programs, the frequency with which employees engage in learning programs, and the popularity of different learning programs and products.

Step 2: Rate Your Company—How Does It Compare to the Best in the World?

After completing the pulse check, CEOs can begin to gauge how their company compares to its peers, its rivals, and the world’s best learning companies. We have established that every company falls into one of four maturity levels (see Exhibit 2):

- Starter Companies. These companies have not yet developed even the most basic building blocks of a learning ecosystem. Typically, they do not have a learning and development function. For these organizations, learning is very much an afterthought.

- Adopter Companies. Although they have adopted some basic building blocks, these companies have significant shortcomings in their learning environment. Typically, while learning is part of an adopter company’s strategy and culture, it is not yet central to the company’s mission.

- Performer Companies. These companies are well on their way to becoming world-class learning companies, having developed the majority of the necessary building blocks. Even so, they still have room for improvement.

- Leader Companies. The few champion companies in this elite category have put learning at the core of their strategy and culture. They perform strongly in most—if not all—dimensions of a learning ecosystem.

Once CEOs know where their company stands in a ranking of corporate learners, they can begin to prepare a roadmap for true change—one that optimizes the environment for learning within the organization.

In a global, cross-industry benchmark of major companies, measuring the extent to which they had turned learning into a competitive advantage, we found relatively few companies (7%) at the starter stage, but many (41%) at the adopter level. About one-third (35%) were performer companies, and less than one-fifth (17%) were learning leaders.

Step 3: Transform Your Business—Prepare a Learning Ecosystem Roadmap

The first two steps of the maturity assessment process—measuring the company’s performance across the five domains and 18 dimensions of the LEMA learning ecosystem framework, and benchmarking the results—provide CEOs with a detailed understanding of the current state of their learning ecosystem. From this foundation, they can create and follow a clear action plan or roadmap.

The learning ecosystem roadmap is like a learning navigation system for a company. CEOs can set their destination—for instance, to become a corporate learning leader—plot their route, and follow the instructions in the form of a set of strategic interventions drawn from an extensive library of best practices. The roadmap is almost always unique, since every company tends to be on its own particular growth path. For example, an adopter company in the IT sector and a performer company in the retail sector are likely to have very different needs.

Even leading learning companies can do more to measure outcomes, embed learning in the day-to-day workflow, and promote a system of credentials and certifications.

Nevertheless, in our survey, we found that most companies share some common strengths and weaknesses. Typically, leaders and performers are good at describing their mission, packaging their learning content in compelling formats, and delivering learning programs through various classroom, online, and other channels. (See Exhibit 3.) But even leading learning companies are less good at measuring outcomes, incorporating learning activities into the day-to-day workflow, and marking the personal achievements of employees through a system of learning credentials and certifications.

Another shared weakness—one that many chief learning officers acknowledge—is companies’ failure to integrate their learning agenda into their corporate strategy. In belief audits that we conducted with L&D leaders from various industries, we found that while 95% of them believed that learning should be a top-three priority, only 15% of them believed that learning constituted a core part of their company’s overall business strategy.

This mismatch may reflect some senior executives’ deep-seated fear that if they invest too heavily in employee learning and development—and offer certification courses that have real value in the wider labor market—they will simply be sponsoring a brain drain of their most talented people. It is true that some employees who undergo expensive training eventually join rival companies. But we see no realistic alternative to investing in the creation of a full-fledged learning ecosystem. Only by doing this, and becoming a talent magnet, can companies recruit and retain the kind of people who will help them adapt and thrive in today’s fast-changing environment.

In our experience, companies that take a cautious, fearful approach eventually face two challenges. First, their best employees actively start looking to join companies that are ready to invest in their personal development. Second, the remaining employees, who have no ambition to leave in search of new and better opportunities, fail to develop new skills and fall behind their rivals in other companies.

So leaders have a stark choice. They can invest in developing a highly skilled and highly adaptive workforce, and accept that they will lose some of their investment when people leave the company. Or they can give short shrift to training, and suffer the consequences of a stagnant workforce that is not incentivized to learn and grow.

We know which choice we would—and do—make.

The Learning Action Plan in Operation: Three Case Studies

The best way to judge the value of a strategic framework is to see how it works in practice. Here, we will present three case studies spanning different corporate learning maturity levels: a learning adopter, a learning performer, and a learning leader.

A Learning Adopter: One of the World’s Largest Airlines

We began our work with a major airline by conducting the benchmark maturity assessment, which yielded a LEMA performance score of 48 out of a possible 100, indicating that the company was a learning adopter. (See Exhibit 4.) Despite its low overall score, the company excelled in two specific dimensions: its learning mission and the variety of channels and formats it used to deliver learning activities. If the company had achieved a comparable level of performance across all five domains, it would have landed comfortably in the learning leader category. In several other dimensions, however, the company’s performance was dire enough to have been typical of a learning starter.

We suggested a series of best-practice interventions designed to increase the company’s learning capability, starting with a focus on improving the assessment of learning needs. Specifically, we advised the company’s executives to pursue a three-step process: first, to systematically segment their employees across business units by hierarchy, job family, skill set, or seniority; second, to identify skills gaps by conducting a mix of self-assessment surveys, manager interviews, and applied analytics of performance reviews; and third, to create targeted learning content for different groups of employees—thereby increasing the value of learning.

A first critical step in gauging a company’s learning needs is to segment employees across business units by hierarchy, job profile, skill set, or seniority.

To give the company’s leaders a practical example of what we had in mind, we pointed to the work of L’Oréal, the world’s biggest cosmetics firm. As it prepared to push forward with an ambitious digital transformation, the French corporation drew up a sophisticated taxonomy of the skills its IT department needed—everything from artificial intelligence and machine learning to algorithms and data warehousing.

After assessing the specific learning needs of individuals in different employee segments, the company was in a position to deploy its impressive array of learning channels and formats more effectively—and to move a step closer to becoming a learning performer.

A Learning Performer: A World-Class Professional Services Company

Our assessment of one of the world’s leading global professional services corporations indicated that it was a learning performer—one maturity level higher than the airline company—with an overall LEMA performance score of 71 points. (See Exhibit 5.) In some dimensions, it was outstanding, earning scores of 96 for its learning mission, 89 for its channels and formats, and 81 for its learning culture. These areas of strength signaled that the company’s leaders saw a link between individual employee learning and the overall success of the company, and that they had established a clear “why” for learning. But in other dimensions—the availability of learning credentials, for example, and the inclusion of learning activities in the workflow—the company was much less impressive.

Our first recommendation to the company was to introduce a system of internal credentials and to partner with external institutions that provide relevant accreditation. The world’s best learning companies do precisely this, for two reasons: it gives them a clear view of who knows what, and it incentivizes their employees. One company that does this especially well is Salesforce, the US cloud-based software company, which has established a full suite of badges that it awards to employees each time they complete a targeted learning activity. These badges are not just ornaments. By gamifying or injecting fun into the learning process, they encourage employees to actively participate in learning programs. They also recognize real achievement and mark individuals for internal promotion.

By gamifying or injecting fun into the learning process, a system of badge awards encourages employees to actively participate in learning programs.

Our second suggestion to the global professional services company was to embed its learning activities in the day-to-day workflow—that is, to schedule the learning programs during the working day, package them in bite-size chunks so employees can easily complete them between essential work assignments, and send individual employees regular reminders or nudges such as short email messages or push notifications about agreed-upon learning objectives. Too often, companies invest in one-off—and sometimes off-campus—training sessions that fail to add value because employees struggle to apply those lessons in their everyday working life.

For a model, we urged the company to look at Google, which has worked out how to deliver the right content at the right time. The technology giant has developed a series of what it calls “whisper” courses—little nudges in the form of “a series of emails, each with a simple suggestion, or ‘whisper’” that executives can act upon in one-to-one or team meetings with staff. For example, one whisper email reminded managers of the importance of showing appreciation for their team members and gave some examples of how to do this, such as by saying “That’s a really thought-provoking point that you brought up because [X].” Other whisper emails covered topics on cultivating trust and sharing feedback.

A Learning Leader: A Global Consumer Goods Giant

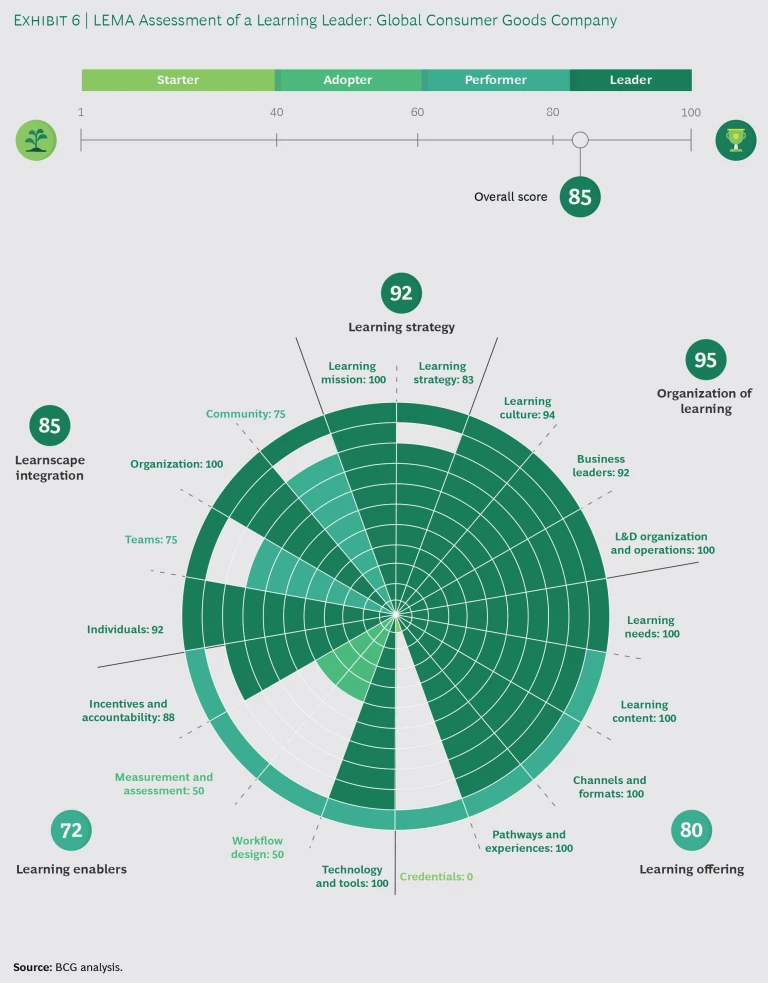

This giant consumer goods firm, headquartered in the US, has an admirable corporate learning capability. When we conducted our benchmark assessment, we gave it a LEMA score of 85 percentage points, meaning that it already ranked as a learning leader. So why should the company look to improve its score? Well, as it turns out, the assessment flagged some striking weaknesses hidden among the company’s numerous strengths.

For one thing, we were startled to find that it had seemingly neglected to develop a learning credentials program. (See Exhibit 6.) So we advised the company’s leaders to address this as a matter of urgency.

We were also surprised to find that, despite all the time and money the company had invested in learning activities, its leaders had dedicated little effort to tracking employees’ progress and establishing the overall value of the learning ecosystem. To put this right, we advised the company to create a set of business-related KPIs for measuring the learning achievements of individuals and teams and for establishing the ROI of learning for the whole enterprise. To complement this initiative, we also recommended that the company introduce a comprehensive learning audit encompassing a self-assessment by individual employees, a report by a dedicated learning advisor, and a review by the employee’s line manager.

Again, we encouraged the top executives to look at the best practices of other companies. In this case, we pointed to the example of Audi, the luxury automobile manufacturer. It runs a two-hour virtual training course for employees in its service and dealership divisions. Online, employees enter a virtual dealership, where they must deal with challenging scenarios, including demanding and belligerent customers. How do they cope? How do they compare to their coworkers? As soon as they complete the course, they—and their bosses—can get immediate answers by checking a barometer that reflects the mood of the virtual customer. If they do well, they collect points that might increase their chances of promotion. In addition, they can review the performance of coworkers who take the course.

Learning = Growing = Thriving

It is a truism that if you’re not growing, you’re dying. But how do you grow? Very simply, you need to find sources of competitive advantage. For the most part, companies compete on the price and quality of their goods and services; on their ability to influence suppliers, customers, and others in their network; on their capacity to recruit and retain talented people; and on their agility and adaptability in a fast-changing world. But if they are to succeed, they must also compete on their capacity to learn.

In fact, we consider a functioning learning ecosystem that provides durable, highly transferable, in-demand skills at scale to employees and teams across the organization to be the principal source of competitive advantage in business today. You may have the most affordable products, the highest-quality services, the most talented workers, and the nimblest organization, but if you’re not learning—and learning fast—you will almost certainly struggle to compete over the long haul.

Learning is essential for growing, and growing is essential for thriving. This is why we place so much importance on a company’s corporate learning capability.

How good is yours?