Managing uncertainty has always been part of the executive remit. But rarely have leaders been forced to tackle volatility in so many areas all at once. The COVID-19 crisis has underscored just how interconnected people, markets, and events have become. As the novelist Nadeem Aslam wrote, “Pull a thread here and you’ll find it’s attached to the rest of the world.”

In an interlocked global economy, triggering events can quickly set off a chain reaction. Before April 2020, for example, few would have predicted that the price of a barrel of oil would fall below zero. But as the pandemic forced communities around the world into lockdown, the cessation of air and road travel lit a match to kindling that was ready to burn, with a growing oil glut, simmering tensions among the world’s major producers, and the ever-present desire of commodity traders to be made whole from a deal. As the expiry date for May’s crude contracts loomed, investors had to pay buyers to take the oil off their hands, an upside-down arrangement that sent prices cratering.

One might argue that such scenarios are exceptional. Yet even before the pandemic, businesses faced a growing number of potential destabilizers—whether in the form of a digital challenger with a better and cheaper way of serving a core market, an extreme weather event, a massive data breach, or a table-turning change in trade policy. These and other destabilizers aren’t going away. As value chains become more intertwined and networks more global, an ill-timed spark could send finely crafted forecasts up in flames.

BCG’s research has found that some organizations are much better than others at managing this degree of uncertainty. A few even thrive on it. They find opportunities in places where others aren’t looking and shore up their organizations so they can anticipate volatility earlier and spring back faster. These companies have what we call “uncertainty advantage.” With the right data, processes, commitment, and mindset, others can build this advantage into their organizations, too.

You Can’t See the Galaxy with a Microscope

Nearly all businesses do multivariate modeling. Nearly all have protocols to tamp down risk and anticipate exposures, and nearly all have business continuity plans to provide operational resiliency. Yet the reality is that many organizations aren’t approaching these activities in the right ways. They’re focusing too much on the near term and relying too heavily on familiar patterns at the expense of counterintuitive ones.

During the COVID-19 crisis, for example, many leadership teams acted decisively to preserve liquidity, bolster revenues, and adapt working arrangements. But these were mainly short-term actions in the traditional crisis response playbook. With forecasts in flux, the priority for most leaders was getting through the next few months and quarters. Few businesses had the stomach to consider bolder course corrections or look for silver linings in the downturn that could position their businesses for greater long-term success.

Most companies haven’t built the capabilities to manage, much less thrive, amidst uncertainty.

The reason for this, we believe, is that most companies haven’t built the capabilities to manage, much less thrive, amidst uncertainty. They lack the robust sensing skills needed to reveal value-creating or value-destroying trends. They don’t have processes in place to evaluate and prioritize multiple strategic options and exploit them in creative ways. And they haven’t adequately prepared their organizations to anticipate and respond to upheaval.

The need for these capabilities isn’t new, but the long bull market over the past decade provided a cushion, allowing companies to fall back on conventional modeling and strategic planning rather than modernizing their approaches. The COVID-19 crisis means that companies now have a lot of catching up to do and a smaller window in which to master the learning curve. But an uncertain future is no excuse not to prepare.

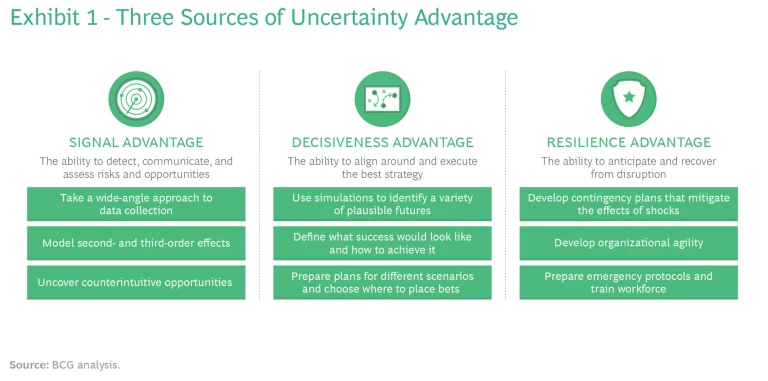

The good news is that companies don’t need to reinvent themselves to gain uncertainty advantage. They just need to become better at detecting signals, more decisive in acting on them, and more proactive in building practices that foster resilience. (See Exhibit 1.)

Signal Advantage

Leaders know that betting on new technologies, products, markets, and skill sets is crucial, but the wrong choices can have punishing consequences. Out of a desire to avoid undue risk, businesses can get locked into a cycle of analysis paralysis, delaying key decisions until they acquire information that they feel they can trust. Yet a small cadre of organizations with superior sensing capabilities have been able to move forward with greater confidence. They have developed a more expansive view of potential risks and opportunities and a more nimble way of interpreting inputs. They have cultivated “signal advantage.”

Businesses with signal advantage take a wide-angle approach to data collection, gathering information under a range of headers, from macro topics like the economy, the environment, and geopolitics to business-specific areas such as customer, market, and technological trends. Instead of tracking 5 or 6 variables, for example, as many organizations do, they track 70 or 100. Advanced modeling tools allow them to interpolate this data, develop early-warning systems, and draw patterns out across different time horizons to see how impacts grow, weaken, or mutate.

For these companies, trend analysis is not only about gathering signals, it’s about probing the fact base and asking questions like “How might these trends combine in surprising ways?” and “What actions would a disruptor take in this situation?” Google cofounder Larry Page, for example, is famous for challenging engineers to think about what could be true, even if unlikely, and to imagine opportunities that conventional wisdom would say are impossible.

Strong deductive capabilities allow companies to go deep, applying insights from a single source across the enterprise. And strong inductive capabilities allow them to go wide and ask, “What might this outlying piece of data foreshadow?” For example, an agricultural insurer created a business that is now worth upwards of €100 million per year by using high-altitude imagery to assess grassland production and model feedstock harvests. This signal intelligence improved the company’s underwriting processes and helped it create a novel pasture insurance product, filling an unmet need for livestock farmers.

Decisiveness Advantage

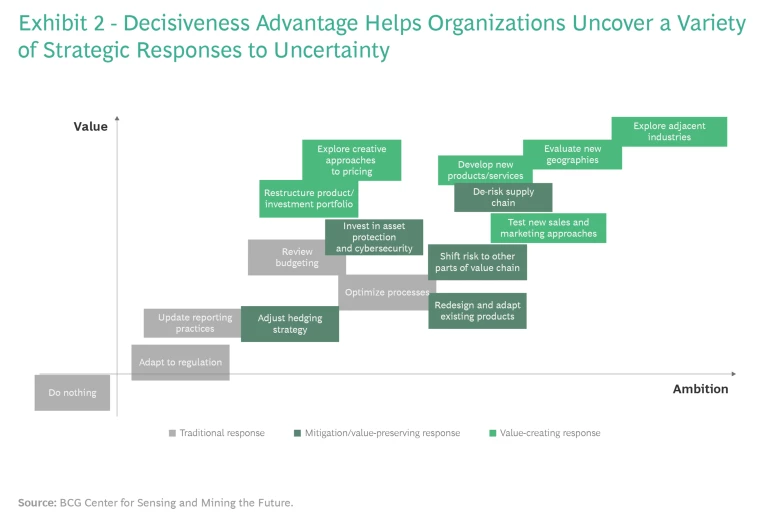

No analytics, no matter how robust, can precisely predict the future. But businesses with uncertainty advantage don’t require precision to act. Instead, they look for chinks in the chain in the form of strategic openings and unexploited opportunities. Using simulations, war gaming, and trend forecasts, teams develop strategic choices under a variety of plausible futures and pressure test strategies against a diverse set of outcomes. Individuals are encouraged to develop not only out-of-the-box ideas, including new business models, products, and services, but also the conditions for success—for instance, external coalitions, joint ventures, lobbying, and other factors that could help nudge the desired scenarios into reality.

These exercises can take the form of workshops for big, “change the organization” initiatives. But many successful scenario-building efforts involve little more than a few hours with sticky notes or a whiteboard. The key is encouraging an open-minded examination, making brainstorming a regular practice, and keeping it grounded in a clear set of objectives. The analysis should consider the business case for each scenario holistically, factoring in financial requirements, projected returns, legal and regulatory complexity, market acceptance, and technical feasibility. Establishing the right practices and rewarding employees for their contributions are also crucial. These steps build organizational learning and inculcate a “what if” mindset that conditions teams to consider innovative alternatives as part of business as usual. (See Exhibit 2.)

Rich sensing capabilities and a methodical visioning process enable organizations to pursue ambitious plays. Consider Toyota, which in 1993 made a big gamble. It anticipated that fossil fuel prices would rise in the years ahead and that fuel-efficient cars would be the next trend. Company leaders reviewed their strategic options. One of the boldest was to develop a vehicle that could run on green technology and be mass produced. The company set an aggressive target, committing to launch, by 1997, not only the first commercially viable automobile with a hybrid-electric engine but also one that would improve fuel efficiency by 100% over the average vehicle. The project’s leader marshaled 1,000 engineers to work on the initiative, ultimately unveiling the car two months ahead of schedule. Today, Toyota is the top seller of hybrid cars and Prius is a household name.

Resilience Advantage

Uncertainty advantage also requires the ability to bounce back from the direct and indirect impact of negative events. Companies that have cultivated this ability are able to triage system shocks and regain operational stability quickly, without throwing the organization into chaos. To acquire this “resilience advantage,” leaders look at the evolving business and macroeconomic landscape and consider what demands it might place on their organization, what capabilities they might need, and what no-regret moves and contingency plans to make.

A decade ago, the leaders of a rail company wondered how to make their business more resilient in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. They laid out a range of scenarios, including one that explored the consequences of the European Union’s hypothetical dissolution. Brexit still lay in the future, but the Eurozone was convulsed by the sovereign debt crisis, and squabbles over austerity measures had intensified national divisions. As part of their strategic-planning exercises, the company’s leaders gamed out what would happen if the EU broke up. Where should they situate their business? How would they access needed parts and materials? Then they imagined what a winning business would do to prepare for such a shift. As a result, even before the UK referendum on Brexit, the company was launched down a new path. It had established a footprint in neighboring Ireland, created new freight routes, and reduced its reliance on the single market. Having played with the idea of what it might do in a similar situation—as well as in other scenarios—the company was able to be more proactive and expansive when planning for an event like Brexit.

Businesses with resilience advantage cultivate options, agility, and attentiveness, which allow them to devise multiple ways to reach their goals. They consider the resources they will need and begin laying the groundwork to acquire them. They also prepare their workforce. Harvesting lessons from previous crises, they establish emergency protocols for business continuity and disaster recovery and run preparedness drills that give employees a playbook to use. Thinking ahead gives the organization dexterity when a negative event occurs, removing confusion and reducing the risk of error.

Companies need to become better at detecting signals, more decisive in acting on them, and more proactive in fostering resilience.

A leading technology device manufacturer knew it had to take preemptive action when modeling revealed risks to its supply chain. For a business that shipped an average of 1.7 computers and one printer per second, even a day’s delay in acquiring needed parts could have widespread ripple effects, slowing production, creating distribution bottlenecks, and disgruntling customers. To get the advance warning it needed, the company created a visualization tool that pulled in weather data, pollution data (which might force a supplier’s plant to temporarily shut down), trade forecasts, and other information. When a risk event tripped a predefined trigger, the system sent managers an automatic alert. The managers had been trained on the new protocol and were empowered to activate the prescribed business continuity plan, be it using a backup parts supplier, a different logistics provider, or some other option. Despite destabilizing events such as flooding in Jakarta, an earthquake in Asia, and a port strike in the US, the business met its fulfillment commitments. The changes reduced risk detection and response times from 28 hours to just 1 hour, a 96% improvement.

Leading Through Uncertainty

The less stable a situation, the more important it is for senior leadership to play a hands-on role. For example, early in the pandemic, when there were fewer than 20,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the US, CEO Jeff Bezos sent Amazon’s staff a memo announcing that he was assuming a direct role in managing the company’s response to the crisis: “My own time and thinking is now wholly focused on COVID-19 and on how Amazon can best play its role.” The memo telegraphed the company’s commitment and ambition and let everyone know that the response to the crisis would be anything but business as usual.

Active leadership is crucial during times of uncertainty. Top managers must demonstrate through board resolutions, CEO speeches, purpose statements, and other means that they believe in the new initiatives. Likewise, they must be willing to invest resources in terms of capital, people, and time. In addition to setting the strategic course, leaders need to build adaptability into their organizations, encourage a focus on the unexpected, and make it acceptable for teams to challenge assumptions and identify new pathways to growth.

Finally, they need to make their findings available and actionable. Using projections and scenario analysis, leaders can communicate new business practices, engage with stakeholders, disclose related risks and opportunities, and successfully communicate their plans to the market.

Getting Started

Uncertainty is uncomfortable. Going boldly into the future comes with anxiety. Rather than seeking to eradicate uncertainty, top-performing organizations create the conditions for living with it successfully. Change won’t always happen overnight, but it doesn’t have to.

BCG’s research has found that the companies that performed best over the past decade experienced just as much turbulence as their peers, with shareholder returns dropping by 27% on average. But these businesses turned uncertainty into advantage by scanning the landscape, orienting themselves to new circumstances, deciding how to respond, and acting quickly. With experience and expertise, their uncertainty advantage grew and their tempo accelerated. The 25 companies in the S&P Global 1200 Index with the strongest TSR over the last decade recovered faster from the 2008 crisis and rebounded higher, ending the decade with EBITDA margins that were more than five times higher than those of their peers.

These companies proved that crisis can spark transformation. Other companies can do the same. For leaders interested in building uncertainty advantage, we offer these starting suggestions:

- Make a list of five commonly held assumptions about the business and imagine that each one has been shattered. Consider what might trigger these events, how the company should position itself in light of them, and the investments, divestments, and partnerships it should make. Thought exercises like these can lead to breakthroughs. It’s how Southwest created the first low-cost airline. Its leaders imagined a scenario in which there were no travel agents, no assigned seats, and only one type of plane, among other shifts. Then they worked to create that future.

- Find the shortest path to launch. Take a counterintuitive idea with high potential and chart what it would take to become reality in your organization. Where are the rough patches? Innovative companies are zealous about removing these points of friction. They design processes that allow them to go from ideation to action quickly. They integrate sensing capabilities into day-to-day decision making, deploy scenario-building and war-gaming tools in direction setting, and put the right tools and resources within easy reach of project teams.

- Empower employees to challenge the status quo. Questioning existing norms and ways of working can feel like a high-risk, low-reward proposition for many employees. To elicit the best inputs, leaders need to model curiosity, create playful workspaces, and forge an active learning organization that celebrates and rewards experimentation.

Most of all, stop moving uncertainty advantage to the side of the desk. Imagining the future will always seem less important than dealing with today. Periods of crisis only exacerbate the tendency to retrench. By tracking signals, visualizing what the world might look like three or five years down the line, and imagining what it will take to win that future, organizations can take uncertainty from a scary abstraction to a practice that energizes the workforce and reshapes performance for years to come.