In many countries around the world, restarting the economy while also fighting the coronavirus has turned into a protracted and arduous slog. Some countries that seemed to be on the cusp of decisively controlling the virus, such as Germany, have recently experienced new outbreaks and hot spots. Others, such as the US, are seeing a rapid rise in infection and hospitalization levels that may signal uncontrolled virus transmission. Both situations have forced select national and regional governments to delay reopening schedules and, in some cases, reimpose targeted lockdowns.

A small subset of governments, mainly in the Asia-Pacific region, have been able to do things differently. Early in the pandemic, these governments were able to decisively contain the spread of the coronavirus, and a few are on the path to total elimination. For example, in early June, New Zealand’s government announced that the country no longer had any active coronavirus cases. Although New Zealand has reported a few new cases since then—mainly due to breakdowns in its strict quarantine rules for travelers from abroad—infection levels remain miniscule, allowing the economy to reopen and people to live and work much like they did before the outbreak. Other governments that largely contained the virus in the first phase of the pandemic include those of Australia, China (after the initial outbreak in the province of Hubei), South Korea, and Taiwan.

These governments have taken what we refer to as a crush-and-contain approach, which has proven the most effective strategy for combating the coronavirus. This approach has resulted in the best health outcomes in terms of preventing virus transmission, and evidence suggests that it minimizes the economic costs of the pandemic. After all, the sooner a country can limit the spread of the virus after it first appears, the shorter the period that the economy will be frozen, and the sooner people can get back to work. BCG’s modeling estimates that the cost of a successful crush-and-contain strategy is dramatically less—approximately 30% to 40% less—than other approaches to fighting the disease.

For politicians and policymakers in the rest of the world, however, the critical question is this: Does crush and contain remain a viable strategy today for governments that were unable to contain the spread of infection in the early phase of the pandemic? Or is it simply too late?

We believe that the crush-and-contain strategy is not only viable, but also more relevant than ever.

We believe that the crush-and-contain strategy is not only viable, but also more relevant than ever. It is indeed late, but it is not too late. It is becoming increasingly clear that despite the focus on reopening the economy, there is no sustainable path to reviving consumer spending and safely putting people back to work unless the virus can be contained. What’s more, our research and modeling show that governments can successfully crush and contain the virus—even when their societies are already experiencing high levels of spread—at a lower cost than they could pursue other, less aggressive approaches.

In order to effectively deploy a crush-and-contain strategy, however, many governments at the national, regional, and local level must significantly up their game. First, they must position themselves to contain the virus in the long term, either by nipping virus transmission in the bud when it first appears or by crushing any major outbreaks of infection through strict lockdowns. Second, during necessary lockdowns, governments must develop the three components of a long-term containment strategy: comprehensive virus monitoring, detailed guidelines for safer interactions, and policies to protect the borders of containment zones. In this respect, crush and contain isn’t just a strategy, it is a dynamic system with four interlinked imperatives:

- Take a more rigorous approach to lockdowns. After nearly seven months of sustained economic pain, no one welcomes further lockdowns. And yet, in many parts of the world, lockdowns are once again on the agenda. The imperative is to make them effective. In order to crush the spread of infection, lockdowns must be extremely strict and have high levels of compliance. Fortunately, the more effective a lockdown is at reducing contact, the shorter it needs to be, and the less it will hurt the economy. We estimate that if a lockdown is strict enough to reduce social contact by 80% from prepandemic levels, it can decisively crush infection transmission in five to eight weeks, depending on the current level of infection.

- Take a more targeted approach to virus monitoring. A comprehensive virus monitoring system, including widespread testing and tracing, is critical for containment. But testing and tracing is most effective at the very beginning of a pandemic and once it is successfully crushed. When infection levels are already high, virus transmission will quickly outpace the ability of societies to track it. In such situations, testing and tracing need to be carefully targeted toward the most vulnerable segments of society , not only to save the lives of those most threatened by COVID-19, but also because doing so is the best way to reopen society safely.

- Take a more customized approach to reopening guidelines. As a society begins to reopen, governments must combine general protocols for safer interactions, such as requiring that people wear masks, with additional guidelines that are carefully customized to the unique circumstances and risks of different economic sectors and population segments. Our modeling suggests that by instituting custom guidelines for safe interactions, governments can reduce the expected peak infection level in some economic sectors by an additional 85% on top of what can be achieved by using general practices alone.

- Enact stronger policies to protect the containment border. Finally, governments must develop the capacity to protect the borders of containment zones in which the crush-and-contain strategy is being implemented. As important as policies are to ensure biosecurity at the national frontier , so too are policies that protect borders of a specific region, state, or metropolitan area—as well as those that protect the borders separating the especially vulnerable population from the general one. Indeed, the best way forward for many societies is to progressively implement a crush-and-contain strategy in regions of the country or for segments of society where the need is greatest.

Many governments missed the opportunity to crush the coronavirus in the early phase of the pandemic. They should prepare now to make sure they don’t miss the opportunity yet again.

Should it neglect any of these imperatives, a government is likely to become trapped in a suboptimal equilibrium in which uncontained transmission will continuously undermine the restarting of the economy, leading to significantly higher costs in terms of human lives and economic destruction that will happen in successive waves. Many governments missed the opportunity to crush the coronavirus in the early phase of the pandemic. They should prepare now to make sure they don’t miss the opportunity yet again.

How the Crush-and-Contain Strategy Optimizes Health Outcomes and Economic Impact

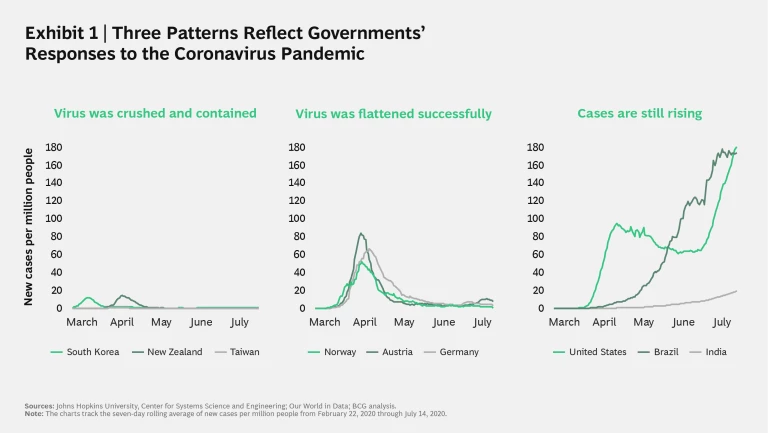

Roughly seven months into the coronavirus pandemic, the growth in new cases has fallen into three distinct patterns. Exhibit 1 charts the seven-day rolling average of new cases per million people in nine sample locations.

Key insights include:

- Governments that crushed and contained the virus (represented by South Korea, New Zealand, and Taiwan) were, for the most part, quick to respond to the first signs of infection spread and crushed it decisively. Taiwan moved the fastest—so much so that it never had a significant outbreak.

- Others represented in Exhibit 1 faced much larger outbreaks. The three European governments (those of Austria, Germany, and Norway), however, were able eventually to bring the growth in new cases down considerably—although still at levels roughly ten times higher than those in the previous category.

- Finally, some governments (such as those of Brazil and, increasingly, India) have experienced nearly uncontrolled transmission, characterized by consistent growth in the seven-day average of new cases. Meanwhile, the US originally saw case growth fall slightly and then remain on a too-high plateau before spiking again.

The patterns in Exhibit 1 demonstrate that the crush-and-contain strategy produces better health outcomes in terms of limiting infection spread. All things being equal, it also tends to minimize the economic costs associated with fighting the coronavirus pandemic.

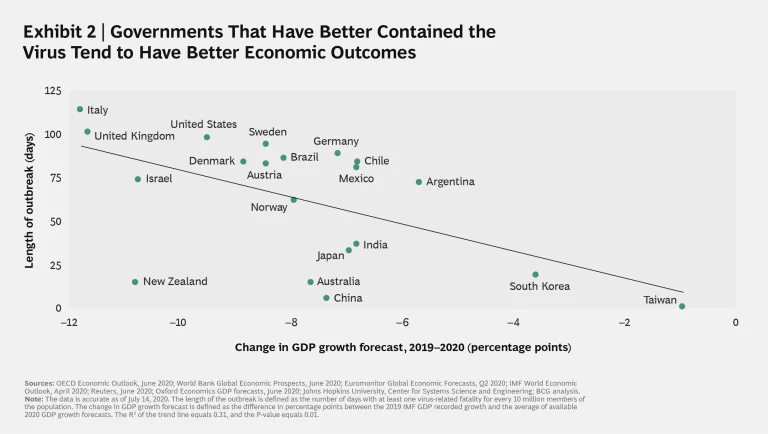

Exhibit 2 provides an illustration of this cost advantage, using the length of infection outbreak as an indicator of how well each government contained the virus and correlating these responses with respective GDP growth forecasts.

Three findings stand out:

- A statistically significant correlation exists between the length of the outbreak and the negative impact on future GDP, accounting for about one-third of the observed difference. In other words, effective containment curbs the economic costs of the pandemic. This finding is in line with recent research showing strong correlations between the level of infection spread and declines in consumer spending.

1 1 See Raj Chetty, et al., “How Did COVID-19 and Stabilization Policies Affect Spending and Employment? A New Real-Time Economic Tracker Based on Private Sector Data,” NBER Working Paper No. 27431, June 2020; available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w27431. - The best-performing governments, those of South Korea and Taiwan, took a crush-and-contain approach and were therefore able to avoid society-wide lockdowns by moving fast to contain virus transmission before it really took off.

- Governments that effectively implemented a crush-and-contain strategy but also needed to impose lockdowns, such as those of New Zealand and China, did less well. New Zealand particularly is an outlier because of its outsized economic reliance on its travel and tourism industry—which has been severely impacted by the country’s strict restrictions on foreign visitors—and due to its high dependence on international trade.

BCG’s modeling confirms the basic economic advantage of the crush-and-contain strategy. Understanding why this is the case requires digging deeper into the dynamics of lockdowns to crush infection spread.

Lockdowns: Early, Stringent—and Short

Not all governments that have pursued a crush-and-contain strategy implemented lockdowns. Taiwan’s government, for example, was able to rely on a world-class testing-and-contact-tracing infrastructure and on widespread compliance with practices such as mask wearing to stop infection spread, and therefore avoided lockdowns. And not all crush-and-contain governments that instituted lockdowns did so across their respective societies. Some, like the governments of China and South Korea, took a more targeted approach. But others, those in New Zealand and Australia, for instance—did institute society-wide lockdowns.

Our modeling shows that once infection spread crosses a certain threshold, lockdowns will be a necessary first step in breaking the back of virus transmission. The precise location of that threshold will vary by country or region depending on a complex variety of factors, including the existing capacity of intensive care units (ICUs) in local hospitals, the speed with which governments can ramp up a testing-and-tracing infrastructure, and the ability to subsidize those who cannot work under lockdown.

What the experience of the crush-and-contain societies suggests, however, is that if a government is going to impose a lockdown, it should adhere to two steps. It should institute the lockdown as early as possible in the event of uncontrolled virus transmission, and it should make the lockdown extremely strict (without imposing too high a cost on society). The more effective a lockdown is at radically reducing interpersonal contact, the faster a society will crush the spread of infection. And the sooner a society does this, the shorter the lockdown needs to be, and the less of a negative impact it will have on the economy.

BCG has developed an “epinomic” model that allows us to dynamically simulate the interlinkages between infection spread and economic impact. The model (initially developed for a European country and designed for developed economies with relatively high levels of urbanization) uses epidemiological and macroeconomic data, as well as assumptions on interaction levels and population mixing, to estimate the combined health and economic consequences of various approaches to imposing a lockdown. We have been using this model to help governments around the world run scenarios and test and refine their restart strategies.

A lockdown needs to reduce interpersonal contact by at least 80% from prepandemic levels.

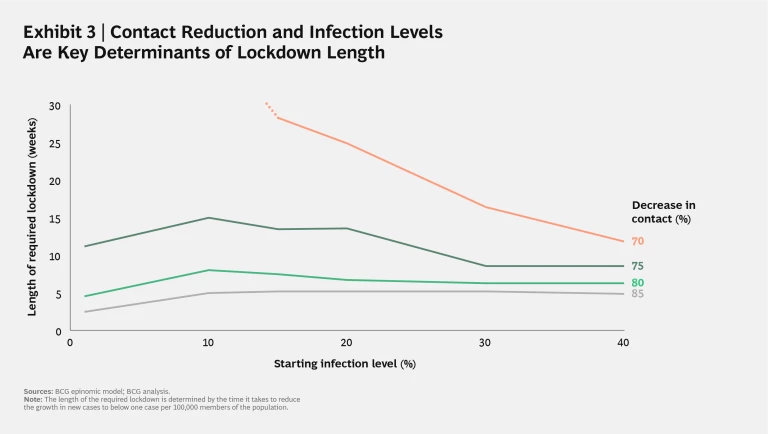

Our model sheds light on the tradeoff between the necessary length (and, therefore, cost) and strictness of a lockdown. Based on the experience of the early crush-and-contain governments, we estimate that to decisively crush infection spread, transmission needs to be reduced to fewer than one new case per day for every 100,000 people in a given population. Our simulations suggest that to reach that threshold in a reasonable amount of time, a lockdown needs to reduce interpersonal contact by at least 80% from prepandemic levels (assuming no behavioral modifications such as widespread mask wearing). If contact reduction doesn’t reach that 80% level, the required lockdown to crush infection spread becomes progressively much longer and the costs to society more expensive.

Exhibit 3 charts the length of time in weeks required to reach one new case per day for every 100,000 people at different levels of contact reduction and infection spread. The exhibit suggests that if governments hit that critical 80% contact-reduction figure, a lockdown can achieve its goal of crushing growth in new infection spread in roughly five to eight weeks, which is in the range of the most effective lockdowns that governments imposed in the early phase of the pandemic. However, once contact reduction falls to 75%, the necessary length of the lockdown increases to between 9 and 15 weeks. And if a lockdown is only successful in reducing 70% of contact occurrences, the length of the lockdown at some levels of infection goes literally off the chart.

Another key insight from Exhibit 3 is that as long as a lockdown reaches the 80% contact-reduction threshold, the level of infection in a given population does not really impact the time and cost required to crush infection spread. As the exhibit shows, the length of lockdown does increase somewhat as the infection level rises, but once that level reaches approximately 10% of the population, the length of required lockdown starts to flatten or even decline. As infection levels rise, lockdown time increases to about eight weeks, increasing the cost by a manageable 17%. But once infection levels reach approximately 15%, the time—and costs—of lockdown begin to decline again.

Although this finding may seem counterintuitive, consider the analogy of a forest fire. When the fire has just begun, it is relatively easy to stamp out; when it is raging, it is difficult. But once a critical mass of the forest is consumed, the ability of the fire to spread is limited by the lack of fuel. The dynamics of transmission spread are similar. While initially higher infection rates require a longer lockdown period, once the infection level reaches 15%, the necessary lockdown time likely decreases, assuming more members of the population will have developed some immunity and, in the near term at least, will not pass on the virus.

We have also modeled the cost implications of various positions on the tradeoff between strictness and time when it comes to lockdowns. In comparing a crush-and-contain lockdown to a less aggressive baseline scenario, we found that if a government can succeed in crushing infection spread in a lockdown of seven and a half weeks (roughly corresponding to the maximum time necessary to achieve an 80% reduction in instances of contact), the economic losses will be approximately 30% to 40% less than in the baseline scenario. (See “Modeling the Cost Implications of Different Lockdown Approaches.”) However, if a crush-and-contain lockdown is less effective in contact reduction, due to poor compliance on the part of the populace, for example, the length of the lockdown would have to be longer and the costs in lost business revenue and unemployment support higher. At a lockdown of 16 weeks, the two scenarios break even. But at a lockdown of 25 weeks, the crush-and-contain strategy becomes cost prohibitive—25% more expensive than the baseline scenario. In fact, a low-compliance crush-and-contain strategy is really no different, both in terms of health outcomes and economic costs, from just partially flattening the curve.

Modeling the Cost Implications of Different Lockdown Approaches

For our baseline scenario, we modeled a government that imposed a lockdown of only moderate strictness and that had some success at flattening the curve, but that didn’t crush infection levels decisively before reopening the economy. This is the situation today in much of the US. We compared this baseline scenario to one in which a government imposed a much stricter lockdown, substantially crushed infection spread, and then, once infection levels were low and under control, reopened the economy. Then, we modeled the costs of different versions of this second crush-and-contain scenario over a six-month period, varying the length of the time it would take to crush infection spread.

Our model assumes that the costs of the lockdown in the crush-and-contain scenario will be higher in the short term because of its increased strictness. However, we also know the costs will be lower than those of the baseline scenario once the lockdown is over, due to the likelihood in that scenario of sustained business closures and continued unemployment support in the course of a more phased reopening of the economy. Therefore, the cost advantage of the crush-and-contain strategy is dependent on the speed at which it can crush virus transmission and then return to business as usual.

In summary, the fact that a crush-and-contain strategy can still work and be cost-effective at relatively high levels of infection helps explain why it is still relevant to places where case counts are currently high. For example, China was able to successfully pursue this strategy after initially losing control of infection spread in Hubei province. Still, a government that implements a crush-and-contain strategy must be fully invested in its efforts. If the initial lockdown is too loose to crush virus transmission, costs escalate, placing society in a worst-of-both-worlds situation of expensive but ineffective lockdowns that do not control infection spread.

Transitioning from Crush to Contain

Strict lockdowns have the advantage of effectively crushing infection spread. They also help governments buy the time to develop the critical capabilities necessary to contain virus transmission in the long term. These include a comprehensive virus monitoring system, detailed guidelines for ensuring safer interactions, and policies to protect the border of the containment zone. All three are critical to the long-term containment essential to any plan for restarting the economy.

A Comprehensive Virus Monitoring System. A comprehensive testing-and-tracing infrastructure is necessary to save lives (so-called “diagnostic testing” to identify those individuals with COVID-19) and to prevent transmission (so-called “sentinel testing” to determine infections levels in society as a whole). A key reason that South Korea and Taiwan were able to avoid the disruption of society-wide lockdowns is that they already had such a system in place , largely due to their previous experience with the SARS epidemic, and could therefore identify and respond quickly to new cases by imposing quarantine on those infected and their contacts. Virus monitoring is also critical to containing transmission over time by allowing the quick identification of any new hot spots of infection.

A comprehensive testing-and-tracing infrastructure is necessary to save lives and prevent transmission.

However, the coronavirus is so contagious that, should infection levels in a society pass a certain threshold, infection spread will quickly outpace a country’s testing capacity and its ability to trace the growing surge in infections . The US, for example, has considerably expanded its testing capacity since being caught short in the early days of the pandemic, conducting nearly 15 million tests in June, or roughly three times the number conducted in April. But as cases surged in late June and early July, testing demand surged with it, creating new shortages and lengthy delays in getting testing results, and most tracing efforts were overwhelmed.

As a rule of thumb, if the test-positivity rate for both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections exceeds 5%, not enough people are being tested to get an accurate picture of the extent of infection in a given population. In such situations, where testing capacity becomes a constraint and the math of exponential infection spread makes tracing almost impossible, governments need to take two key steps.

The first is to embrace pooled testing—a technique in which multiple samples are combined into a single sample—to learn quickly whether any infection is present in the pooled population. If so, progressively smaller pools are tested until the infected individuals are identified. The approach was developed in the 1940s for sentinel programs to track the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and has been used by organizations ranging from the US military to the Red Cross and in a broad cross-section of countries including China, Germany, Ghana, Israel, Rwanda, and the US (beyond the military). The great advantage of pooled testing is that many people can be tested quickly and cheaply to identify any infection in a population. Preliminary research suggests that at low infection rates, pooled testing can test an equivalent number of people at approximately 30% to 45% of normal testing volume.

The great advantage of pooled testing is that many people can be tested quickly and cheaply to identify any infection in a population.

Pooled testing is especially important once a society starts to reopen because it can be targeted toward specific groups of people in workplaces, schools, and other locations with easily identified populations of employees or students. Here, the emphasis should be on environments—restaurants, gyms, and nursing homes, for example—that pose a high risk of superspreading, which is responsible for most virus transmission. For businesses where the risks of transmission are especially high, “zero-tolerance” pooled testing is a worthwhile approach, whereby the employees are regularly tested in a pool, and if any part of the pool comes back positive, the entire group goes into quarantine until those infected are identified by additional testing.

In addition to using pooled testing to extend the reach of existing resources, governments dealing with high levels of infection should also target limited testing-and-tracing capacity on the most vulnerable and exposed segments of the population—for instance, the elderly with comorbidities, nursing home residents, health care workers, or those in underprivileged communities. In the US, for example, an important priority should be to set up testing centers near communities of color, which have higher-than-average levels of infection and yet 15% fewer testing sites than found in predominately white communities. Focusing scarce testing resources on protecting the vulnerable is good policy, both because it saves lives and because it is the most effective way to achieve better health and economic outcomes for society at large.

Focusing scarce testing resources on protecting the vulnerable is good policy, both because it saves lives and because it is the most effective way to achieve better health and economic outcomes for society at large.

Safer Interactions. Lockdown crushes infection levels by radically limiting social interactions. But when it comes to simultaneously reopening the economy while also continuing to contain virus transmission, it’s imperative to make social interactions safer as individuals begin to congregate in restaurants, stores, workplaces, schools, and other institutions.

By now, most are aware of the general practices that reduce the spread of infection—such as physical distancing, frequent hand washing, and the widespread use of masks. And many governments have already developed detailed guidelines for key workplace settings, schools, and public transport as part of the phased reopening of the economy. But what most governments do not yet have is a clear understanding of which specific practices are most effective for a given economic sector. Without this understanding, it is difficult to assess tradeoffs and to decide where to focus scarce resources.

Our epinomic model sheds light on this question and helps demonstrate the power of customizing interaction guidelines by economic sector or population group. Take the example of education, which has recently become a major focus of reopening efforts in many countries. Governments increasingly recognize that restarting education is a critical priority, both to ensure that an entire generation of students does not fall behind and to free up parents to return to work. As countries develop plans to restart local school systems, cities and regions worldwide face the challenge of designing effective practices to ensure that students and their teachers stay safe and do not become vectors of infections for their families or for each other.

Any school’s reopening plan, however, must address two hard realities. First, reopening only makes sense once infections levels and the growth in new cases are already under control. Otherwise, reopening is likely only to pour more fuel on the fire. Second, reopening will inevitably result in more cases than would have existed if schools had remained closed. BCG recently assessed a European government’s school-reopening plan. Its country has relatively low infection levels, and general guidelines such as mask wearing are largely in place. Our modeling suggested that if no additional steps are taken to ensure safer interactions in the schools, reopening would result in approximately 35,000 additional new infections, of which about 700 would require hospitalization in an intensive care unit (in a nation with a total ICU bed capacity of only 1,300).

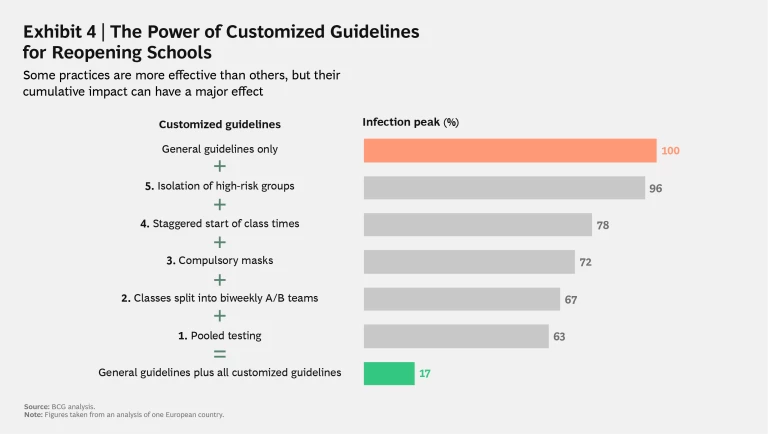

We also modeled the likely individual and cumulative impact of five potential practices tailored to ensure safer interactions in the country’s education sector. (See Exhibit 4.) We found that some practices would likely be limited in their ability to reduce virus transmission. For instance, isolating high-risk groups of students is a no-regret move to protect those vulnerable individuals, but it would have a minimal effect on the estimated peak infection rate, reducing it by only 4% on average, because there simply aren’t enough students with preconditions to have a major impact. Staggering the start of class times in order to minimize crowding in hallways at the start of the day and in between classes would be a much more effective step, reducing peak infection by 22%. But the most effective measures, by far, were to split classes into biweekly “A/B teams” (such that half the class attends school for two weeks, and then the other half attends for the subsequent two weeks, and so on) and to institute pooled testing. We estimated that these two steps would reduce peak infection by 33% and 37%, respectively.

The truly critical insight, however, is that combining all the steps listed in Exhibit 4 would result in a massive cumulative reduction of 83% in peak infection rates in addition to the reductions achieved by following the general guidelines alone. By implementing all five of the education-specific practices, the government would be able to cut its additional number of school-related infections down to 6,000, and its need for additional ICU beds for severely ill COVID-19 patients down to 10.

This analysis is a specific example of a more general principle: governments need more sophisticated analytical tools to make contact in key institutional settings as safe as possible and to model the different economic and social benefits and costs of certain types of interactions . The more refined and granular governments can get in their recommendations, and the more customized they can make practices for specific situations, the more effective they will be at ensuring safe interactions and limiting infection spread. At the same time, they will also minimize the negative economic impact of the coronavirus, allowing their societies and economies to reopen safely.

Protected Borders. Finally, effective containment also requires that governments exert effective control of the border to the zone in which the crush-and-contain strategy is being implemented. In order to contain virus transmission to manageable levels, a society must have the ability to isolate or otherwise protect itself from any infected individuals entering the containment zone from the outside.

Most attention about protecting borders has focused on international frontiers, and a number of the crush-and-contain governments have imposed stringent border restrictions. For example, New Zealand currently restricts foreign nationals from entering the country, and citizens and permanent residents are tested upon reentry and forced to quarantine for 14 days. Similarly, all persons arriving in South Korea are required to take a viral test upon arrival, to quarantine for 14 days (even if the result is negative), and to download an app that monitors their state of health and reports it to authorities daily during the quarantine period.

As economies open, bilateral and multilateral agreements are likely to become more common among societies that have crushed and contained the coronavirus. For example, the governments of Australia and New Zealand are discussing the creation of a “trans-Tasman COVID-safe travel zone” that would allow free travel between the two neighboring nations without the need for quarantine. Conversely, the inability of a country to decisively contain virus transmission will likely result in severe travel restrictions for its citizens, as demonstrated by the recent directive from the European Union to exclude travelers from the US, Russia, and Brazil when it reopened its borders to international travel in July.

But the principle of protecting the border does not apply exclusively to the lines dividing nations. Governments need policies for protecting containment zones from external contagion also at the level of specific regions or municipalities and for specific population segments. In China, all citizens are assigned to a risk-stratification category via a code in a mobile app. The categorization is based on the individual’s health status and the level of infection risk in their region. The app indicates who is cleared to resume work, study, or to travel between different regions within country. In Australia, the three states of Western Australia, South Australia, and Queensland emerged earlier from lockdown than others, but remained shut to travelers from other states with substantial community transmission. And even in the US, which is far from having contained infection spread nationwide, a few states are implementing increasingly rigorous travel restrictions on travelers, especially from states with high infection levels. (See “Crush and Contain in a Single US State.”)

Crush and Contain in a Single US State

Nevertheless, Hawaii moved quickly in the early weeks of the pandemic to institute a mandatory 14-day quarantine for new arrivals (violators face up to a $5,000 fine and up to a year in prison), as well as a statewide stay-at-home order, and established perhaps the most extensive testing-and-tracing system in the US. As a result, by mid-July, Hawaii had the fewest COVID-19 cases per capita of any US state, with only 21 fatalities—although a new spike in infections in July has led the state to keep its mandatory 14-day quarantine in place until at least September 1st.

Beyond universal travel restrictions or quarantine policies, creating effective border protection involves some combination of the following steps: a methodology for categorizing new entrants by degree of risk (with appropriate restrictions for high-risk categories), fast and efficient testing at the border zone, and quick action to isolate and trace contacts should an outbreak occur. These principles can be applied not only to specific geographic regions, but also to especially vulnerable population segments . For example, South Korea carefully protects the figurative border between nursing home residents and the rest of the population by closely monitoring the health and travel histories of staff and visitors.

Remaining Vigilant

The evidence shows that a crush-and-contain strategy works. It delivers far better health outcomes at a lower cost to the economy, and it can be applied on a local scale and even at high levels of infection. It is the best way to build the sense of public safety, as well as the consumer and business confidence, on which sustainably restarting the economy ultimately depends.

But creating an effective crush-and-contain system requires political will, realism about the necessary investments and the likely time frame, and a willingness to act decisively and quickly to any signs that virus transmission is getting out of control. The coronavirus isn’t going away, and its capacity to spread rapidly is extremely unforgiving of any breakdowns in containment. Constant vigilance is key.

Creating an effective crush-and-contain system requires political will, realism about the necessary investments and the likely time frame, and a willingness to act decisively.

Not even the successful crush-and-contain governments are immune. Early in the pandemic, Australia implemented an effective crush-and-contain strategy, nearly eliminating locally acquired cases. But in July, the state of Victoria had to reimpose a six-week lockdown for some 5 million people in the Melbourne metropolitan area after active cases tripled to nearly 1,000 in a brief nine days, pushing local contact tracing resources to their limit. The reason: a breakdown in hotel quarantine processes for foreign travelers led to some private security guards acquiring and then transmitting the virus just as the Victoria region was reopening after its initial lockdown.

And yet, if the story of the Melbourne lockdown is partly a cautionary tale, it is also an illustration of the kind of decisive action on which a successful crush-and-contain strategy ultimately depends. In order to win the fight, you have to fight to win.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their BCG colleagues Lorenz Pammer, Keerthana Raju, and Bryann DaSilva for their contributions to the epidemiology modeling, research, and analysis in this publication.