A raft of powerful and structural challenges to the chemical industry has surfaced, in part, but not entirely, because of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the industry has already had to deftly navigate product commoditization, shifting consumer attitudes and regional preferences, and regulatory changes over many decades, the dynamics today are unique and more potentially disruptive than ever before. Taken as a whole, they affect the entire value chain and are driving a tectonic shift in the chemical industry that has been a long time in the making.

Because these challenges and their impact are tightly interconnected, chemical companies must take steps to view them holistically, navigate them, and find ways to benefit from them. That will mean a complete reexamination of how value is generated in light of the new pressure points the companies face. And they must be certain that these reoriented value levers are operational and targeted, combined with clear metrics to determine their efficacy while supporting objectives for future growth.

Uncertain Looming Demand and Profitability Cliffs

The primary challenge that many chemical companies face is volatile and often declining demand, a trend that will affect chemical segments and applications differently. Between 2015 and 2019, median chemical company sales gains held at 3.8% per year, virtually in line with global GDP growth. But many chemical companies—particularly those targeting the European and North American markets—cannot expect that type of growth anymore.

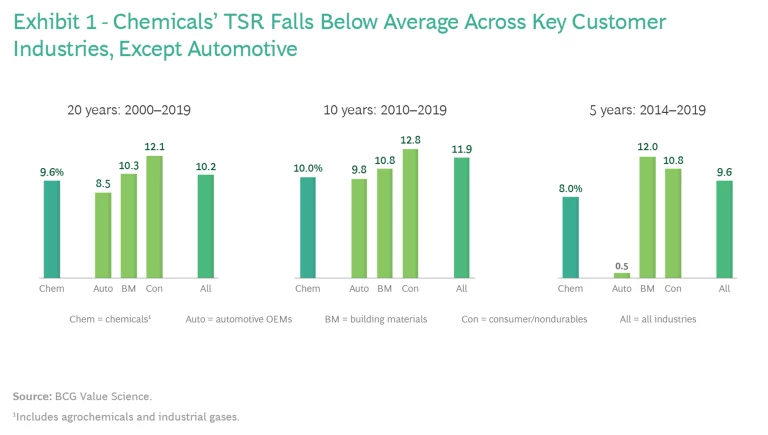

Indeed, chemical companies’ value creation is already showing troubling signs. For the past two decades, total shareholder return in the chemicals sector has not only lagged behind the average of all industries but also behind the results of its key customer sectors, including construction and nondurable consumer items. (See Exhibit 1.) By this metric, chemical companies have outpaced only the auto industry.

Why the concern about the chemical industry? One explanation is “chemophobia,” an especially relevant worry for segments that supply chemicals for consumer goods products, including single-use plastics. Worried about their health and the environment, some consumers are seeking alternatives for products that contain high amounts of chemicals. Reacting to this, some chemical companies are beginning to take steps to adopt circular economy methods, which involve continuous recycling of feedstock and materials throughout the production process, reducing energy and resource consumption. However, although recycling at scale is imperative, for chemical companies it will constrict virgin feedstock demand and other volume flows.

Equally threatening to volume and profitability are reductions in the amount of chemicals needed for specific customer applications, a trend propelled by customers themselves.

Equally threatening to volume and profitability are reductions in the amount of chemicals needed for specific customer applications, a trend propelled by customers themselves. Aided by digitization, customers, especially industrial manufacturers and makers of consumer products, are developing in-house capabilities to better assess the value, quality, and quantity of materials and products they are buying from chemical companies. With more knowledge about their specific needs, customers can more easily switch chemical suppliers based on reliable apples-to-apples cost and product comparisons, thereby influencing chemical prices and the composition of chemical products with more certainty than before. Similarly, customers can increasingly make educated decisions and be proactive about replacing chemicals’ current ingredients with more sustainable ones.

Global issues are also undermining chemicals’ profitability. Such issues include trade wars, local content regulations, minimal IP protections for chemical companies in some countries, and a growing consensus that long-distance shipments of high volume/low value products are wasteful and environmentally unsound. All of these things collectively shift the contours of chemical production and distribution from a global to a more regional profile.

New Demand Pockets Are a Double-Edged Sword

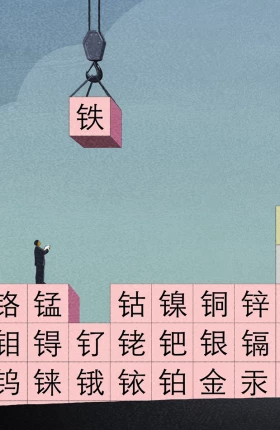

On the plus side, chemical companies can find some comfort in the potential for new emerging demand pockets. For instance, chemical-related products and solutions are poised to play an essential role in the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables. To illustrate, in the automotive arena, the shift toward electric vehicles (and possibly hydrogen-powered cars) and autonomous driving will sharply reduce the need for certain plastics used in fuel tanks and under-the-hood applications. But at the same time, EVs will require a wide range of new chemicals-driven solutions for batteries, vehicle lightweighting, electrical components, and thermal insulation.

Similarly lucrative new demand pockets will also emerge in other industries. But these new markets are anything but easy wins for chemical companies. To improve their attractiveness and applicability, chemical companies will have to develop fresh sets of skills to rapidly enhance chemical properties and functionalities. For example, polymers and adhesives used in mobile communication devices will not only have to meet structural specifications as they do today but also be much lighter. That’s how they will satisfy new equipment requirements designed to minimize interference and enhance performance without adding weight.

Many of today’s materials and manufacturing advances involve contributions from multiple industries and technologies, combining digitization, artificial intelligence, and “ecosystems” of companies to streamline value chains.

Because of the deepening competitive landscape, chemical companies are facing a tough battle for these new demand pockets. Many of today’s materials and manufacturing advances involve contributions from multiple industries and technologies, combining digitization, artificial intelligence, and “ecosystems” of companies to streamline value chains. In these arrangements, the revenue and profit streams for chemical companies are less favorable than before. A prominent example is the 3D printing market, in which software, solution, and equipment providers are the center of value generation and power, while standardized polymers—the essential medium for the printing activities—from different chemical players are interchangeable.

Whether chemical companies can take advantage of the new demand pockets and monetize innovation will depend in part on how much they embrace digital solutions. To expand product properties and applications, chemical companies will need to adopt data accumulation and analysis tools for market intelligence. Thus far, companies have generally not adopted digitization sufficiently to readjust their business models to meet the emerging challenges.

Moreover, the coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated some of the pressures on chemical companies. For instance, the virus amplified the need for more resilient global supply chains—chiefly, more regional manufacturing and distribution—as mid- and long-distance shipments were hindered. And with face-to-face sales more difficult, only those chemical companies that had already digitized go-to-market and sales activities and adopted digital customer collaboration tools were at a distinct advantage.

Reexamining Value Levers

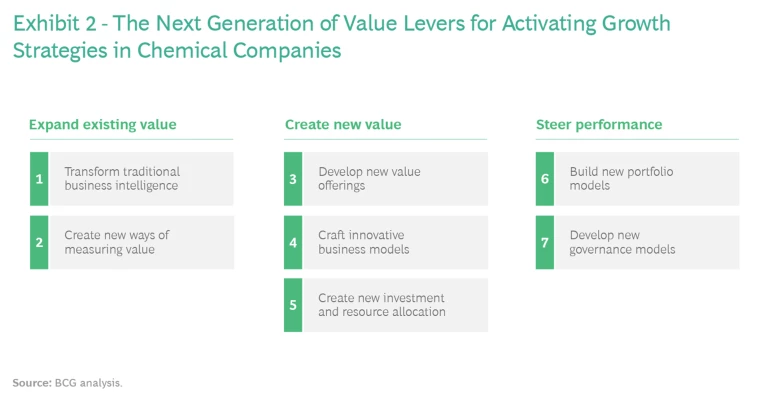

The extent of the interconnected driving forces pressuring the chemical industry is broad and complex. To address these forces, chemical companies may need to take a bold step: reassess the seven core value levers that most induce growth in the industry, reorienting them to support planned initiatives and transformation efforts (if any) and to overcome the current disruptive challenges. (See Exhibit 2.) By reexamining these value levers, chemical companies can accomplish a series of critical and interwoven goals.

The first is to focus on expanding existing value by improving and modernizing business intelligence (BI) and developing new ways to measure value (value levers 1 and 2). The second is to create new value through fresh offerings from new business models, driven by new investment and resource allocation paradigms (value levers 3, 4, and 5). The third is to steer performance by transforming portfolios to better reflect changing value chains and end industries, while designing new governance frameworks to support critical business models and operations (value levers 6 and 7).

Let’s examine each of the seven value levers in turn.

1. Transform traditional business intelligence into value chain oriented, “always-on” radar.

Today, business intelligence at chemical companies often has a product-dominated bias and tends to downplay the importance of gathering essential information about growth-producing activities across the value chain. Such activities include customer applications, possible regulatory changes, and shifting customer attitudes and preferences. Moreover, the supply and demand disruptions caused by COVID-19 also revealed substantial BI gaps in external supply-chain-related customer and supplier data.

By enhancing the capabilities of their BI systems, chemical companies will be able to better target product and service offerings to match their skills, expertise, traditional market strengths, and shifts in customer needs.

By enhancing the capabilities of their BI systems, chemical companies will be able to better target product and service offerings to match their skills, expertise, traditional market strengths, and shifts in customer needs. Such changes include, for example, polymer-related demand as automakers increase their output of electric vehicles. Moreover, companies with enhanced BI will be in an excellent position to add value by streamlining the value chains they operate in as well as reducing their number to some degree. It may be more valuable to be a “core partner” in a few concentrated high-precision value chains, providing innovation and specialization for sustainability practices, as opposed to being a peripheral commodity provider in many different ones.

The following are key questions that chemical executives might ask themselves as they reposition their business intelligence. (For a full list of questions for this value lever, see “Questions for Transforming Your Business Intelligence.” Note that in subsequent sections describing each of the seven value levers, we will likewise include sidebars with complete question lists.)

- Do you have full transparency on a granular level of the key customer value chains that you are serving? (That is, not the automotive industry, but rather the EV battery value chain; not the construction industry, but rather the buildings’ decorative coating value chain).

- Can you identify the likely “demand cliffs” and “growth pockets” in each value chain that you are operating in?

- What is the status of your “business risk intelligence” in your value chains? This includes both potential logistics and supply risks but also regulatory and customer sentiment risks (for example, are you fully aware of your product ratings in end customer apps like Code Check?).

Questions for Transforming Your Business Intelligence

- Do you have full transparency on a granular level of the key customer value chains that you are serving? (That is, not the automotive industry, but rather the EV battery value chain; not the construction industry, but rather the buildings’ decorative coating value chain).

- Can you identify the likely “demand cliffs” and “growth pockets” in each value chain that you are operating in?

- What is the status of your “business risk intelligence” in your value chains? This includes both potential logistics and supply risks but also regulatory and customer sentiment risks (for example, are you fully aware of your product ratings in end customer apps like Code Check?).

- Is your current business intelligence approach dominated by a product focus? (“We are number two in XYZ chemical!”)

- Do you have end-to-end supply chain information and metrics (including customers and suppliers) for your most relevant value chains?

- Do you know the “innovation pivot areas per value chain”? Where in your different value chains are the key specifications being defined? Are you in the position of a “specification taker” or can you shape application and product specifications in your value chains?

- Do you have a clear view on which kinds of value your products are providing to your customers’ products, devices, and solutions while “in use”? Do you have a view on how to measure the “product-in-use contribution”?

- Do you clearly know the “compromises and pain points” customers incur when doing business with your company?

- Do you have a clear idea of the implications of digital initiatives on your customers and your customers’ customers? How will these change your go-to-market models?

- Do you have a good understanding of the potential new-growth pockets driven by downstream innovation and likely regulatory changes?

- Do you have a clear view on changing downstream value chains driven by technology changes and/or industry convergence (for example, automotive battery value chains, closed-loop recycling value chains for food packaging, etc.)?

- Do you have a target picture for your specific business segments regarding what “zero CO2 emissions (downstream) and circular economy at scale” will really entail? Which of your current business segments will face “end of volume growth” and by when?

- How can your innovation efforts contribute to a greatly increased utilization of downstream products? (five- to ten-fold durability, precise product-in-use measurement, close to 100% recyclability, etc.)

2. Create new value metrics that go beyond financial reporting.

Performance metrics often are rather narrowly focused on typical balance sheet and profitability items, which look backward. As a result, they fail to provide sufficient information and guidance for portfolio, technology, operations, and people decisions relevant to current chemical industry conditions.

A much more useful and enlarged set of standardized value metrics for the chemical industry should be centered on three goals:

a) Making ESG (environmental, social, and governance) KPIs and targets operational, not just for chemical companies’ own operations but also for their entire value chain.

b) Developing rules for CO2 footprint reduction and for adopting circular economy principles.

c) Identifying ways to evaluate company assets that are often neglected; namely, employee diversity, skills, and capabilities.

Awareness of the materiality and business relevance of ESG factors has grown in recent years, but metrics for gauging compliance are far from standardized. Accounting for CO2 footprints is equally inconsistent. For instance, some companies report carbon emissions from only their direct operations (Scope 1 on the Greenhouse Gas Protocol scale) and their energy use (Scope 2), while neglecting to measure Scope 3 upstream emissions, which are generated by the production and distribution of the feedstock, intermediates, and materials they purchase. Since Scope 3 upstream emissions constitute more than 50% of the carbon footprint for many chemical companies, overlooking these numbers renders the result useless.

Have you translated your ESG targets into specific metrics and objectives and compared them with investors’ expectations and competitors’ goals?

Accurate and standardized tracking of ESG metrics and targets across chemical value chains will surely be mandatory in the future, affecting everything from required allocation of recycled raw materials in end products to adhering to social standards, such as outlawing child labor globally. Similarly, the skills and capabilities of companies and their workforces, especially those related to technological developments and innovation, will increasingly be highly sought-after. Likewise, unambiguous measurement protocols will be crucial to maintain the support of stakeholders and investors.

Questions to ask when developing new standardized value metrics for ESG and internal capabilities include:

- Can you fully calculate the CO2 footprint of your products—caused by both your own operations and purchased products and feedstock—and use these insights to inform portfolio management, innovation strategy, and other important functions?

- Have you translated your ESG targets into specific metrics and objectives and compared them with investors’ expectations and competitors’ goals?

- Have you designed metrics to provide findings about skills and capabilities by job profile and across the company—in other words, are you doing strategic workforce planning?

Questions for Creating New Ways of Measuring Value

- Can you fully calculate the CO2 footprint of your products—caused by both your own operations and purchased products and feedstock—and use these insights to inform portfolio management, innovation strategy, and other important functions?

- Have you translated your ESG targets into specific metrics and objectives and compared them with investors’ expectations and competitors’ goals?

- Have you designed metrics to provide findings about skills and capabilities by job profile and across the company—in other words, are you doing strategic workforce planning?

- Do you know the degree to which your most relevant suppliers adhere to ESG principles?

- Do you have respective full life-cycle analyses (LCA), including product disposition, reuse, or recycling?

- Do you have transparency on the downstream CO2 savings enabled by your products and solutions, compared with the “next best alternative” (for example, in the context of insulation, lightweight, and durability enhancement)?

- Are you fully aware of your ESP and CO2 related ratings by the various regulatory and private bodies (such a DJSI, Refinitve, CSR hub, etc.)

- Have your defined and communicated a strategic roadmap toward specific and absolute CO2 reduction (“pathway to zero”)?

- Are you fully aware and have you applied transparent product specific allocation rules for both recycled input material and renewables (for example, mass balancing)?

- Are you fully aware and participating in efforts to harmonize the various ESP related metrics and accounting recommendations?

3. Develop new value offerings, responding to changes in volume growth and profit pools.

Demand and profitability cliffs on the one hand, new growth pockets on the other hand, and the full digitization of value chains across different industries will compel chemical companies to focus on value growth to uncork growth streams. For instance, currently the lifetime usage of drilling machines (which contain a high amount of plastics) is only about 30 minutes. Imagine how many fewer drills would be sold if do-it-yourself outlets offered in-store “drilling as a service” and drills were utilized about 1,000 times longer than they are now. To make up for the impact on plastics profits, chemical companies might focus on providing solutions that increase the durability of power-tool casings.

Are you fully aware of the pain points and compromises customers are facing when doing business with your company?

Moreover, new value offerings should address how products and solutions are offered. For example, chemical companies can conduct joint product development with customers using digital collaboration tools and materials based on precise customer preferences. Or chemical companies can use remote monitoring equipment to track the strength, performance, and suitability of catalysts used at, say, polymer plants or refineries. With this data, chemical companies can then share insights with customers about their operations, recommending improvements and participating in their implementation.

Questions to ask when designing new value offerings include:

- Have you created new approaches to capture product-in-use value for your most sustainable products? For example, can you make a product with 30% fewer ingredients by volume that achieves the same desired performance? That way, you could establish customer payments by the number of products produced instead of by the amount of materials in them. Ideally, both the customer and the chemical company can come out better financially in such an arrangement.

- Are you fully aware of the pain points and compromises customers are facing when doing business with your company? Replace these problematic interactions with digitized approaches for repeat business, joint business development, product data capturing, and the like.

- Which feedstock and precursors enable enhanced durability and utilization of your products? Which ones support substantially improved recyclability? Which ones contribute to significant CO2 reduction in the overall product life cycle, including post-use emissions?

Questions for Developing New Value Offerings

- Have you created new approaches to capture product-in-use value for your most sustainable products? For example, can you make a product with 30% fewer ingredients by volume that achieves the same desired performance? That way, you could establish customer payments by the number of products produced instead of the amount of materials in them. Ideally, both the customer and the chemical company can come out better financially in such an arrangement.

- Are you fully aware of the pain points and compromises customers are facing when doing business with your company? Replace these problematic interactions with digitized approaches for repeat business, joint business development, product data capturing, and the like.

- Which feedstock and precursors enable enhanced durability and utilization of your products? Which ones support substantially improved recyclability? Which ones contribute to significant CO2 reduction in the overall product life cycle, including post-use emissions?

- Do you know which of your chemical ingredients end up in customer products that are useless or even harmful to the environment, such as in single-use packaging for, say, body care products used by hotels? It would probably make sense to move away from these segments.

- Do you have a clear view on the “value hierarchy” of the applications you are serving with your products? Chemical companies should segment their products and applications in a “value to the world hierarchy” along the following lines:

- Have you defined joint innovation targets with your customers to further downgauge volume of ingredients?

- Have you defined “value capture” approaches for your ingredients, which enable a much higher durability of your customers’ products (for example, leasing related business models)?

- Have you defined “value capture” for your products, which contribute to downstream CO2 reduction (for example, sharing of saved CO2 surcharges downstream)?

- Have you invested in value chain traceability and supplier quality assurance? And can you realize a value premium by presenting your business to customers as a “most sustainable supplier”?

4. Craft innovative business models.

In order to grow and profit from—and play a crucial role in—the changes in industry value chains and the transition into a decarbonized economy, chemical companies need to improve their innovation programs and alter their business models in three ways.

First, they must tackle difficult problems that will require new chemical solutions and that are going to gain in importance in the coming years. Among them: increasing battery life cycles; implementing zero-loss energy transmission; developing hydrogen as an energy source; or engineering carbon capture and storage systems.

Second, they must shift their core focus—from providing chemicals to offering solutions based on chemicals innovation; in other words, from volume to value delivery. These solutions can come in many forms, such as collaborating with customers on complex job sites, guaranteeing product performance and pricing models, providing application-specific formulations instead of individual chemical products, or “renting out” process chemicals that can be returned by customers after usage.

To better understand and creatively address customer needs, chemical companies should engage in joint research and development activities with downstream value chain partners.

Third, they must anticipate how customer needs might change as global trends and requirements evolve. For instance, chemical companies can create products that facilitate customer participation in the increasingly important circular economy by improving the sustainability of existing chemical applications, designing for recyclability, lowering materials volume, and enabling lightweight solutions.

To better understand and creatively address customer needs, chemical companies should engage in joint research and development activities with downstream value chain partners and be more aggressive about embracing digitization as a tool to scale innovation across value chains. In addition, they should consider involvement in multi-company and multi-industry ecosystems, in which organizations—including suppliers, distributors, competitors, and sometimes regulators—pool resources to more efficiently deliver products and services to a wider customer base. In some cases—for instance, cosmetics and nutrition—chemical companies can serve as ecosystem orchestrators, reaping the highest rewards for leading the network’s product and services development and operations. In other instances, such as applications such as additive manufacturing that require strong high-technology capabilities, chemical companies may be better suited to be contributors but can still turn profits and enjoy market rewards and stability from their participation.

Questions to ask when designing new innovation models include:

- Have you clearly identified the pivot areas of innovation that should garner the most attention in order to succeed in your most relevant value chains, even as they change dramatically?

- Which partners do you need to address these pivotal areas of innovation?

- Have you developed capabilities to orchestrate or contribute to ecosystems in applications where the pivot area of innovation is within your value chain coverage?

Questions for Crafting Innovative Business Models

- Have you clearly identified the pivot areas of innovation that should garner the most attention in order to succeed in your most relevant value chains, even as they change dramatically?

- Which partners do you need to address these pivotal areas of innovation?

- Have you developed capabilities to orchestrate or contribute to ecosystems in applications where the pivot area of innovation is within your value chain coverage?

- Is the portion of your innovation budget that addresses measurable ESG targets sufficient?

- Which innovation activities are needed to measure the “value in use” of your products and to capture the fair share for your company?

- How can you best leverage digital technologies to enhance both effectiveness and efficiency of your innovation efforts?

5. Create new investment and resource allocation.

What’s needed are paradigms that go beyond capital expenditure. By reassessing business intelligence, value metrics, value offerings, and innovation, chemical companies can derive new financial and resource allocation strategies based on more relevant and accurate perceptions of which parts of the business to support. Essentially, investment decisions need to be reoriented along three dimensions.

First, decision makers need a new concept of what company assets are and how they should be cultivated. In today’s landscape, the idea of company assets is expanding to include skills and capabilities for emerging value chains; customer relationships; marketplace intelligence; access to regulatory policymakers; intellectual property and its protection; and freedom to operate in various regions. Moreover, companies need to go beyond the notion of “I must have full control over my assets” or “I need to own it all.” Instead, they should imagine more collaborative ventures and investments that target specific value chain outcomes that are core to their competitiveness and leave the rest to better-suited partners.

Second, decisions should be made around specific value chains that will bring the best returns. This involves exchanging the narrow product view (“We need to increase production capacity of product X to regain market leadership in China”) for building objectives that are specific to value chain capabilities (“We need to improve our ability to capture value in the high-voltage renewable energy transmission ecosystem”).

What share of your resource allocation is targeted toward breakthrough and disruptive improvements?

Third, risk-return formulas should be redesigned, particularly in light of COVID-19 supply chain disruptions that attempt to achieve a greater degree of diversification.

Questions to ask when developing new investment and resource allocation plans include:

- What percentage of your overall investments are allocated toward increasing customer value and improving ESG targets in a measurable way?

- What share of your resource allocation is targeted toward breakthrough and disruptive improvements?

- Do you have clear investment processes and guidelines that support critical aspects of the business beyond capital expenditure, including talent and capabilities?

Questions for Creating New Investment and Resource Allocation Plans

- What percentage of your overall investments are allocated toward increasing customer value and improving ESG targets in a measurable way?

- What share of your resource allocation is targeted toward breakthrough and disruptive improvements?

- Do you have clear investment processes and guidelines that support critical aspects of the business beyond capital expenditure, including talent and capabilities?

- Which percentage is improving ESG targets in a measurable way?

- Do you have a process and metrics in place with respect to allocation of “risk mitigation remedies”—specifically the ability to strike the right balance between efficiency and risk mitigation?

- Do you have an honest view on capability gaps and a respective “gap closure plan” (for example, in the context of missing digital capabilities, circular economy capabilities, and capabilities for successfully orchestrating ecosystems)?

6. Build new portfolio models centered on value chains, business models, and ecosystems.

Business portfolios also need to be reassessed in a multidimensional way, based in part on the insights gained from new business intelligence initiatives and also on the combination of value chains being addressed and the ecosystems that the company is involved in. Portfolios should be analyzed through a lens of new growth pockets and demand cliffs. All of this should form the basis for resource-allocation decisions and help make determinations about which parts of the portfolio the company should retain and which parts can be shed. Portfolio options should include different business models that chemical companies can choose from, depending on their market and investment strategies and the partnerships and ecosystems they form to further facilitate shifting into new value chains.

Questions to ask when developing new portfolio models include:

- Are you able to define your business portfolio by end industry, value chain position, and application?

- Do you have a clear view of your “critical capability portfolio”—that is, the competitive advantages that should be maintained and enhanced and the competitive gaps that need to be closed?

- Are you able to assess your portfolio of value chains by whether you “own positions of power”—that is, do you cover the pivot areas of innovation within the value chain, or are the essential innovations removed from your areas of expertise and outside of your capabilities?

Questions for Building New Portfolio Models

- Are you able to define your business portfolio by end industry, value chain position, and application?

- Do you have a clear view of your “critical capability portfolio”—that is, the competitive advantages that should be maintained and enhanced and the competitive gaps that need to be closed?

- Are you able to assess your portfolio of value chains by whether you “own positions of power”—that is, do you cover the pivot areas of innovation within the value chain, or are the essential innovations removed from your areas of expertise and outside of your capabilities?

- Can you assess your business portfolio in terms of demand cliffs versus new pockets of growth?

- Are you able to evaluate your portfolio by degree of sustainability?

- What does your “portfolio of business models” look like in different value chains? Typical business models driven by the new strategic imperative for chemical companies might be, for example: value chain innovation pacemaker; most ESG compliant product and service provider; niche application and product-in-use specialist.

7. Develop new governance models.

The combined impact of the powerful forces driving significant shifts in the chemical industry—namely, digital transformation, geopolitical changes, and the increasing relevance of sustainable offerings and operations—compel companies to focus more on good corporate governance. One option is adding nongovernmental organization (NGO) leaders to formal governance bodies (such as the board of directors) to diversify decision making.

Chemical companies that have established external advisory boards often use them to focus on keeping the company aligned with its stated ESG policies and goals.

Another noteworthy approach is to appoint more advisory boards that include experts weighing in on digital, environmental, and business model innovation strategies. Such committees could also include people from chemical customer industries and NGOs. Although these boards may lack statutory authority, they should be given complete independence to offer opinions and direction, even to contravene top management points of view—and management should be mandated to take these boards’ direction seriously. Chemical companies that have established external advisory boards often use them to focus on keeping the company aligned with its stated ESG policies and goals.

Questions to ask when implementing new governance models include:

- Does your company regularly assess its board composition, committee charters, and meeting timing and scheduling for effective ESG governance and digital competence?

- Have you integrated ESG fully in governance, including the board’s corporate strategy discussions and management incentive schemes?

- Is sustainable business-model innovation a key responsibility of management, supervisory, and external advisory boards? And are these committees providing input and challenging the company’s “sustainable equity story”?

Questions for Developing New Governance Models

- Does your company regularly assess its board composition, committee charters, and meeting timing and scheduling for effective ESG governance and digital competence?

- Have you integrated ESG fully in governance, including the board’s corporate strategy discussions and management incentive schemes?

- Is sustainable business model innovation a key responsibility of management, supervisory, and external advisory boards? And are these committees providing input and challenging the company’s “sustainable equity story”?

- Do you have annual in-depth reviews of ESG performance, materiality, and targets?

- Does your board include ESG factors in enterprise risk management and risk tolerance discussions? Does this include the whole supply chain and not just the company’s own operations?

- Does your management consider ESG factors in all major investment decisions, business development, and innovation initiatives?

- Does your leadership make ESG explicit in business planning, target setting, performance assessment, and compensation?

- Has your company committed to a management board-signed statement of corporate purpose?

- Does your company release an integrated ESG report?

C learly, chemical companies have their work cut out for them. Changes in their industry are coming quickly now, and they will be long-lasting and have a deep impact. To successfully transition into—and, better yet, lead in—the new future they face, chemical companies must reassess and reorient value levers more quickly and seriously than ever before.