In volatile times such as these, a company’s instinct is to focus on defense—to protect the business from harm. Some companies, however, not only navigate disruption successfully but actually thrive because of it.

These organizations take many forms. They’re the technology companies and oil producers that can tell a political backlash is brewing well before it hits full force and then use their foresight to reposition their businesses ahead of competitors. They’re the equity investors that reap rich returns by snapping up stakes in undervalued—but sound—assets in the challenging emerging markets that others shun. They’re the industrial goods companies that shift production from one country to another because they correctly predict that rising protectionist sentiment in some key markets will lead to trade actions that will alter the economics of manufacturing .

What’s their secret? According to our research, the consistent winners apply a highly developed approach to geopolitical risk management that emphasizes opportunity rather than just mitigation, involves the entire organization, and leverages sophisticated and robust analytical processes.

A Wide Variety of Approaches to Risk Management

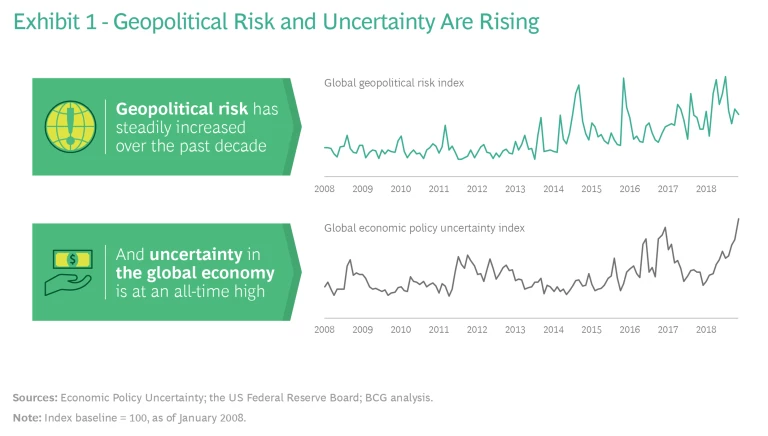

The value of being able to anticipate, synthesize, and harness risk for potential gain has never been greater. Global geopolitical risk and economic uncertainty have increased dramatically over the past decade, according to leading indices. (See Exhibit 1.) What’s more, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought geopolitical risk factors into sharp relief. The ability to proactively navigate turbulence can mean the difference between prospering through a crisis or falling victim.

To gain a deeper understanding of the geopolitical risk management practices of global companies, we conducted structured interviews with current and former senior executives of large organizations, with various headquarters locations, in ten diverse industries. We evaluated their organizations’ approaches along three dimensions: the strategic role of geopolitical risk management within the company, the ways in which different parts of the organization are leveraged, and the use of risk management processes and tools.

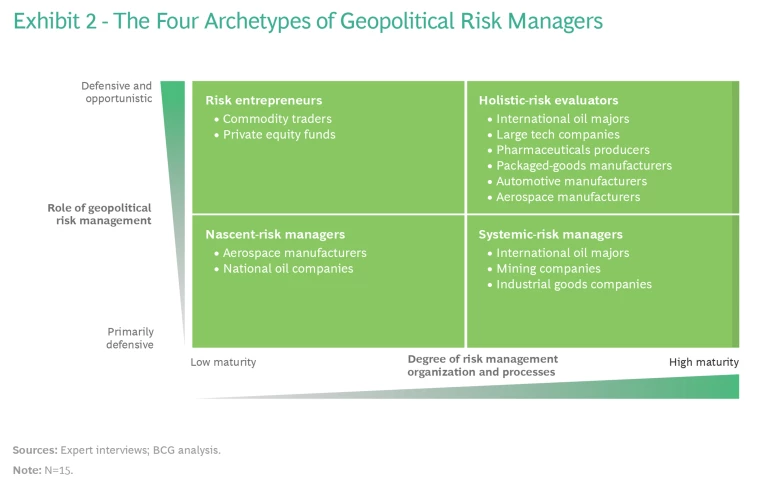

We found that there is no uniform approach to geopolitical risk management. Even leading global companies within the same industry can differ sharply, depending on their corporate cultures and geopolitical risk appetites. We grouped companies into four general archetypes according to the extent to which they recognize and act on opportunities arising from geopolitical shifts—in addition to mitigating the downside risks—and the intensity of focus and sophistication of processes with their organizations. We call these archetypes holistic-risk evaluators, risk entrepreneurs, systemic-risk managers, and nascent-risk managers. (See Exhibit 2.)

Holistic-risk evaluators have the most highly developed geopolitical risk management operations. They view disruption strategically, as a source of opportunity; embed risk management practices across the organization; and use advanced geopolitical-risk-monitoring tools and processes. Not surprisingly, several oil and gas companies—which often make large, long-term investments in high-risk countries amid frequently shifting environmental-protection policies—fall in this category. But so do some pharmaceutical, technology, and packaged goods companies.

Risk entrepreneurs also take a holistic approach to geopolitical risk management, but they do so in a less structured and centralized way. Systemic-risk managers adopt a primarily defensive position, focusing on protecting their businesses from the downsides of change. Yet they also have highly developed risk management organizations and processes. Nascent-risk managers use an almost entirely defensive strategy, with minimal organization and processes.

The Strategic Role of Geopolitical Risk Management

The most successful opportunists carefully monitor any situation that may, at first glance, appear to be a threat. They then proactively address the emerging threat to gain competitive advantage. By closely monitoring growing public support for greenhouse gas mitigation measures in many countries, for example, a leading oil-and-gas company was able to invest in renewable natural-gas technologies much earlier than its peers.

The most successful opportunists carefully monitor any situation that appears to be a threat and then proactively address it to gain competitive advantage.

A major global technology company offers another good illustration. The organization saw a troubling trend in a number of key markets that could potentially threaten its growing cloud-storage business: mounting anxiety on the part of policymakers and customers, who were worried that local governments could access confidential data kept on servers in certain countries. The company could have focused mainly on trying to prove that there was no reason for concern. Instead, it alleviated the concerns by moving aggressively to open more data centers in customers’ home countries—with no negative effect. As a result, the company was able to significantly expand its cloud business and gain advantage over competitors that were slower to act.

Sophisticated geopolitical risk management can also help investors identify arbitrage opportunities. “We are constantly searching for overlooked assets where we can navigate the risk, while others are unwilling or unable to,” an executive of a private-equity firm with a decades-long record of success in emerging markets told us. “Our Asia-Pacific footprint is now a huge advantage.”

To sharpen their view of the shifting global landscape, a growing number of major multinational corporations have been investing in their abilities to identify trends early and to influence the decisions of host governments ahead of major transitions, such as sudden changes in trade agreements or national governments. Companies also have been attempting to measure the impact of their lobbying efforts on governments, such as by benchmarking the success of their advocacy compared with that of their industry peers or estimating potential cost savings.

Quantifying return on advocacy is difficult, however. Sometimes, the payoff is simply that the company can continue doing business as usual. One Western energy company, for instance, credited the skills and transparency of its government relations staff for being able to operate simultaneously in two Middle Eastern nations despite strong political tensions between the two governments.

In extreme cases, a disruptive event can jeopardize an entire business. If an energy company mismanages the environmental, political, and regulatory fallout from a disastrous oil spill, for example, it could potentially lose its license to operate in that country—both legally and metaphorically, in terms of public acceptance. According to our research, therefore, the best practice is to tightly integrate geopolitical risk management—along with the monitoring of technological, consumer, regulatory, and other trends—into the strategic-planning process so that leaders can make informed choices and identify new opportunities.

Involving the Entire Organization

Most companies do not have a dedicated team of full-time employees devoted to geopolitical risk management. Instead, they depend on personnel from government relations, strategy, and other business functions to identify and mitigate risks, with one function coordinating and consolidating input.

Every organization we studied relies on input and expertise from the field.

Every organization we studied relies on input and expertise from the field. Successful geopolitical risk managers tend to hire a cadre of personnel with experience in doing business in the market and dealing with local agencies. To ingrain the importance of external relations throughout their organizations, some companies rotate high performers and potential candidates for upper management into country leadership positions, where risk management becomes one of their duties. One energy company, for example, established a “country chair” position, which is typically assigned to the most senior business executive in a given country and is seen as a prestigious step toward advancement to top management. In addition to their normal duties, country chairs are responsible for liaising with all external stakeholders—including national and local governments, community organizations, and other enterprises.

A strong cross-functional interface is critical, especially for companies that take a holistic approach to risk assessment. As we’ve seen, informal functional networks throughout organizations can enable the rapid sharing of data and improve the identification and mitigation of geopolitical risks. One consumer packaged goods company we studied has developed a strong knowledge-sharing culture among functional networks. Because the company sells its products almost everywhere, problems that pop up in one country often may have already been solved in another. A quick message or email to the global functional marketing, finance, or risk community, the company told us, allows for rapid troubleshooting, the cross-pollination of insights, and the sharing of best practices.

The Use of Processes and Tools

Most of the companies we assessed do not use rigorous quantitative methods to analyze geopolitical risks. In-depth analysis, they recognize, does not come solely from algorithms. The companies with the most disciplined approach, however, often use a combination of processes and tools to look at risks during different time frames and with different rates of periodic review.

A holistic view uses four lenses: global geopolitical trends and scenarios, ongoing operations, investment decision making, and frequent monitoring of evolving events and development that can affect the business. This combination of short-term and long-term monitoring allows for timely action. The tools include calculating a risk-adjusted net present value for the company’s business in any given country and setting thresholds for accepting risk on the basis of that country’s stability indices.

Developing Holistic Capabilities

Building a more holistic and entrepreneurial approach requires action in all three dimensions: enhancing the strategic role of risk management, ingraining it into the organization, and developing robust processes.

Assessing Approaches to Geopolitical Risk Management

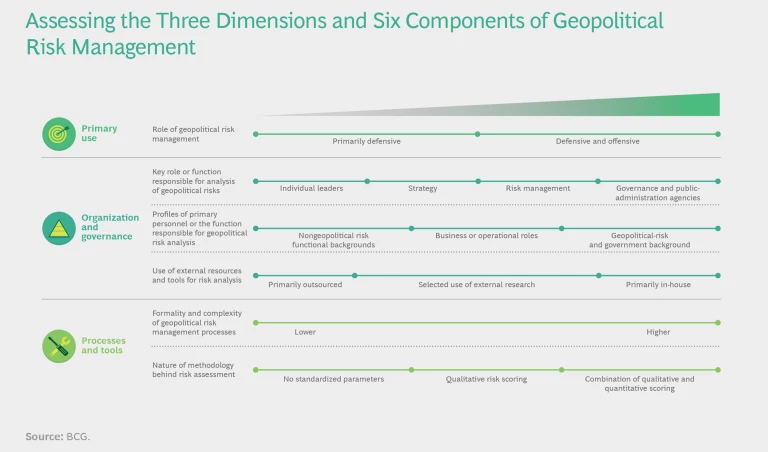

We evaluate three broad dimensions of geopolitical risk management, which incorporate six components, within an organization. (See the exhibit.) The first dimension considers the primary use, and the role, of geopolitical risk management within the organization. The second, organization and government, evaluates the capabilities required to deliver geopolitical risk management. Components of this dimension include the key role or function that is primarily responsible, the profiles of primary personnel or the functions responsible for geopolitical risk analysis, and the use of external resources and tools for geopolitical risk analysis. The third dimension, processes and tools, includes the formality and complexity of geopolitical risk management processes and the methodology used.

To enhance the role of geopolitical risk management and thus create tangible business opportunities, leaders should take the following steps:

- Integrate geopolitical signals and risk assessment into strategic-planning processes and define actionable strategies to both protect the business and take advantage of emerging opportunities.

- Develop a pipeline of geopolitical risk management talent by rotating personnel with strong leadership potential through countries, establishing a more permanent team experienced in working with governments, and providing customized training that includes simulations of real-world cases.

- Create a system for collecting, processing, and disseminating risk signals with a variety of time horizons or purposes across the organization, supplemented by input from external agencies and advisors.

- Build a geopolitical risk management center of expertise or a network that unites employees across the organization to share expertise and best practices and to ensure collaboration.

- Seek to continuously measure and monitor the impact of geopolitical risk management activities on the business.

“In every risk there is also an opportunity” is a well-worn adage. Yet few companies consistently act on it. In a global business environment characterized both by hypercompetition and intensifying geopolitical headwinds, it is no longer enough for companies with global footprints to only react defensively. Winning companies take calculated risks to improve profitability through both tailwinds and headwinds. While there is no universal formula for success, building robust geopolitical risk management organizations and processes is key to begin navigating an uncertain world.

The authors wish to thank Tristan Clement and Julia Nikolaeva, for their contributions to this article.