Digital tools enabled by advanced analytics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning can help companies uncover the fastest and most effective path to abating the O&G industry’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The global oil and gas (O&G) industry has a big problem: it is responsible, either directly or indirectly, for close to half of all global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. As the impact of global warming becomes all too apparent, pressure is mounting rapidly—from activist investors, regulators, employees, and society as a whole—for the industry to change its ways.

Last year, for example, BlackRock, the world’s largest fund manager, rejected 55 board directors of companies that failed to act on climate issues. This year, the organization rejected almost five times as many—including a major O&G company. A court in the Netherlands recently ordered an O&G major to slash its emissions harder and faster than planned. And in some locations, making significant emissions reductions is becoming a requirement to hold a license to operate.

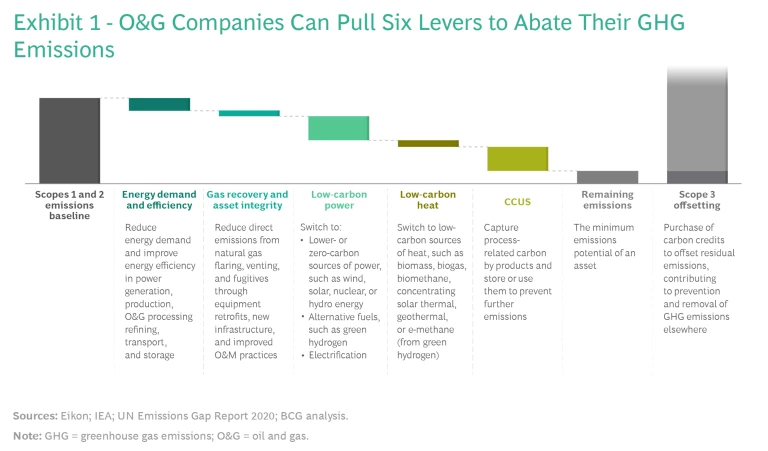

O&G companies can pull six levers to reduce their carbon footprints. (See Exhibit 1.) Nevertheless, most have not succeeded in significantly reducing the scope 1 and scope 2 emissions for which they are responsible. And few have been able to accurately calculate the amount of scope 3 emissions generated by customers—let alone make significant strides to reduce them as well.

By fully integrating these levers into all their operations, however, O&G companies can indeed effectively reduce their direct and indirect emissions. To do so, companies will need to identify and measure their emissions as accurately as possible, determine the optimal means for abating them, execute the abatement, and then provide a full and accurate accounting of their decarbonization efforts.

That’s where digitization—in the form of new tools using advanced analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning—comes in. These tools help companies figure out the fastest and most effective steps to take along the road to decarbonization and provide guidance for executing on those steps. Here’s how they work.

The Context

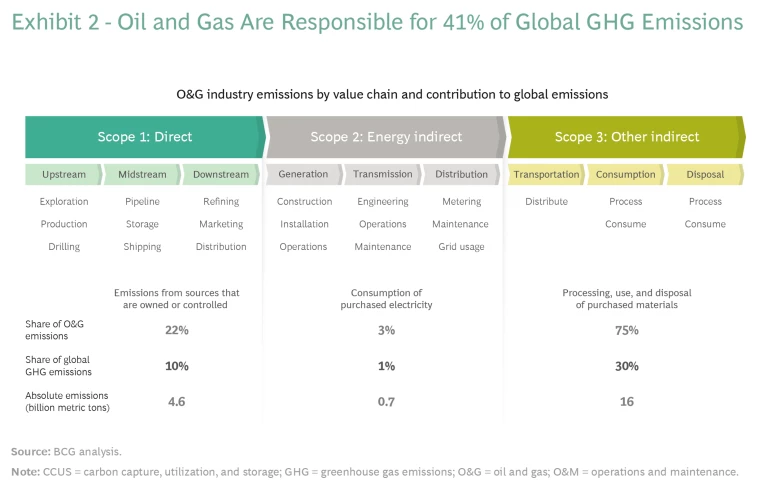

The O&G industry is responsible for 10% of global GHG emissions through its direct scope 1 emissions from operations and another 31% through its indirect scope 2 and scope 3 emissions. (See Exhibit 2.) Given the magnitude of the industry’s emissions, however, simply diversifying into low-carbon energy alternatives will not be sufficient to reduce emissions to acceptable levels.

Companies themselves can decrease scope 1 and scope 2 emissions through operational and energy efficiency initiatives—the fastest, and often lowest-cost, pathway to decarbonization.

Scope 3 emissions must also be significantly limited if the industry is to make a real dent in the world’s overall carbon emissions. But few companies have created targets for reducing scope 3 emissions or are set up to tackle the challenge of understanding their extent and how to decarbonize them. Without visibility into scope 3 emissions, companies will be unable to communicate, commit to, or deliver on their climate ambitions.

Cracking the Climate Code

O&G companies looking to take the next step in their decarbonization efforts, optimize their operations in light of their abatement goals, and provide full visibility into both their direct and indirect emissions must integrate digitally enabled analytics into their DNA. These tools, along with AI and machine learning, can help companies identify the sources and drivers of emissions (their own as well as those of suppliers and customers), reduce energy consumption, and optimize the energy efficiency of their own operations.

O&G companies must integrate digitally enabled analytics into their DNA.

Just such an effort enabled one O&G operator, for example, to identify ways to abate 500 million tons of scope 1 and scope 2 CO2 equivalent emissions, constituting 30% of its total emissions. Of that total, 15% could be abated economically through improvements in operational and energy efficiency, 60% through a switch to lower-carbon power and heat equipment and sources, and 5% through fewer flaring, venting, and fugitive emissions. The company also gained greater visibility into the tradeoffs across abatement initiatives.

The process of full data integration must begin with the development of a precise, credible, and high-quality baseline of GHG emissions. Created through the collection and analysis of both real-time operational data and transaction-level data from suppliers and customers, the baseline helps companies identify the drivers of emissions intensity and uncover abatement initiatives. Quantifying, abating, and monitoring methane emissions, however, is a particularly tricky problem. Digital tools can help companies make considerable progress in this area. (See “Minding the Methane.”)

Minding the Methane

When it comes to methane, however, the challenge is different and considerably harder. Identifying the sources of methane emissions and capturing data on the amount emitted is not easy. What’s more, the margin of error is wide, which makes abating such emissions—especially fugitive emissions—also difficult and results in a considerable degree of uncertainty with regard to accurately reporting progress.

To greatly improve accuracy in measuring methane emissions, companies must obtain observed operational emissions data from multiple sources and multiple vendors across the entire asset portfolio. Once obtained, that data can be fed into a digital platform powered by AI that can integrate it, generate insights, and provide guidance on the action needed to mitigate the emissions.

We have developed a four-prong approach to implement the digital tools needed to help O&G companies measure, abate, and report on their methane abatement efforts.

Holistic Strategy. First, develop a clear coordination strategy for translating methane abatement goals into action, making sure to assess the full complement of measuring and monitoring data needed to meet those goals. There are as many methods of measuring methane emissions—satellite, stationary, and mobile ground detection systems; various analytics products; and many kinds of field services—as there are companies offering solutions. Gathering and managing this wealth of data and services options is no easy task.

Advanced Analytics. Once the strategy is defined, determine which specific insights will enable action, given the available methane data. Then develop the value-based analytics needed to provide these insights on the basis of three key principles. Using advanced analytics is:

- Actionable. With advanced analytics, companies can locate methane emissions, generate automated proposals for reducing those emissions, and develop real-time planning to carry out abatement efforts.

- Valuable. Companies can use advanced analytics to tie specific KPIs to each abatement proposal, including return on investment and emissions reduction data, while preserving the flexibility needed to add additional KPIs.

- Optimized. Advanced analytics can offer proposals, based on fully integrated data, that maximize both abatement and economic value.

Field Services. At the same time, create a unified dashboard providing full visibility into methane emissions across the entire asset portfolio. This will allow operations teams to take optimal and timely abatement action and monitor progress.

Compliant Reporting. Consolidate monitoring data to enable in-depth and transparent reporting of methane abatement progress to regulators, investors, and other stakeholders.

AI-enabled, end-to-end digital platforms are now essential to measure, monitor, and abate methane, as well as to comply with reporting standards and expectations.

The baseline then allows companies to optimize their abatement efforts throughout their operations and business activities. Optimization is a hugely complex process, especially for large, integrated operators, which must seek to optimize every asset across the company—potentially requiring, for example, significant changes in operations and maintenance, field development, governance, and financial accounting. And then, of course, this all has to be put into practice globally.

AI on the Road to Abatement

The role of AI in the abatement journey is becoming critical. It can help companies bring together diverse data sources—often residing in data silos and requiring further analysis and reconciliation—and then apply advanced algorithms to more precisely estimate emissions levels, optimize operations to reduce them, and monitor progress.

Key to the process is, first, to use AI to build the emissions baseline across all three scopes and then to identify the highest value abatement initiatives by simulating and quantifying the potential impact of specific abatement initiatives—all while taking into account asset-specific constraints, financial impacts, and regulatory requirements and constraints.

AI tools can then suggest an optimal strategy for reducing emissions, which companies can use to build an actionable emissions-reduction roadmap for each asset. Ultimately, the roadmap should take into account asset-specific priorities, portfolio-wide initiatives, and organizational constraints.

Then it’s time to put the roadmap into practice. AI-driven process optimization can generate the desired emissions reductions in real time, managing asset emissions and directly monitoring them. Options are already available, for example, to optimize energy efficiency at a processing plant, refinery, or offshore platform. (See “A Winning Combination.”).

A Winning Combination

That’s why predicting the amount of energy consumed and the resulting GHGs produced, along with understanding the underlying levers available to reduce those emissions, are key to the effort of decarbonizing O&G assets. Optimizing operations from the standpoint of energy efficiency can reduce energy consumption by up to 15% while continuing to meet production expectations—making it, in some cases, the most cost-effective and fastest lever for abating O&G assets’ emissions. No capital investments are required, and the gains can be achieved within as short a period of time as 12 weeks from initiation to working proof of concept.

New tools are now being developed and implemented that leverage data to analyze each unit’s working regime, predict the expected energy usage, and support process engineers in their efforts to optimize both energy usage and the resulting GHG emissions. These tools can take into account all the relevant elements of operations, including targets such as throughput and minimum and maximum production yields, and identify optimal unit settings, such as temperature set points, while supporting the effort to test new operational strategies.

The process begins with real-time monitoring of energy consumption at each unit and the related CO2 emissions. The tools look for similar production levels and contextual setups in the available historical data, comparing current and historical efficiency performances. This allows for the determination of a new set of optimal settings for the unit that aim to maintain production safety and continuity while optimizing performance and energy consumption levels.

Finally, these tools can suggest concrete actions that operators can take to move from the current settings toward the optimal ones, with the goal of reducing energy consumption and emissions levels.

Greater energy efficiency, lower costs, and fewer emissions—a win all around.

Options to manage energy use at the earlier stages of upstream production are also available. (See “In Search of Lost Time.”) In addition, the roadmap provides the means to monitor progress in reducing emissions across assets and the entire abatement program.

In Search of Lost Time

As with many industrial processes, time is money. In the case of drilling for oil and gas, time also means the release of GHG emissions—both directly, in the form of flaring and from the use of machinery such as the drilling rig itself, and indirectly, in the form of scope 2 emissions released by the providers of the energy used. It is estimated that so-called invisible lost time (ILT)—inefficiencies resulting from the difference between the actual time it takes to complete a task and the best-case scenario, as well as suboptimal drilling routes and inadequate data—can increase the time it takes to drill and complete a hole by as much as 60%, boosting a company’s carbon footprint proportionally.

Nonproductive time (NPT)—caused by situations in which drilling progress is halted for operational or geomechanical reasons, such as stuck pipes and total fluid losses—can also significantly affect the time to reach the target depth and increase the resulting overall carbon footprint.

While a variety of digital solutions have been long available to drillers to better manage their energy use, new AI-based tools are now coming online that can decrease both ILT and NPT, effectively reducing operational time by 50% or more. These tools gather data from a variety of sources and vendors and then leverage a combination of machine learning, statistics, and physical models to provide real-time targets along with guidance on how to achieve them. Not only can they show drillers just how to drill and identify the best drilling routes, but they can also determine the processes and drilling directions that will use less energy and reduce the risk of events leading to NPT.

While working with one exploration and production client to reduce ILT, we found that these tools decreased drilling time by as much as 75%, depending on the nature of the geology encountered. They increased tripping and casing speed by more than 20%, reduced hole-cleaning time by more than 50%, and decreased connection time by more than 25%. Overall, operational time declined by half, reducing scope 1 and scope 2 emissions by at least 50%, and events leading to NPT dropped by 70%.

The Scope 3 Challenge

As critical as it is to reduce scope 1 and scope 2 emissions, the difficult truth is that for most O&G companies, scope 3 emissions can account for 90% or more of their total emissions footprint. What’s more, building a reliable, high quality, and granular scope 3 emissions baseline, and then working with suppliers and customers to abate their emissions, is an enormously complex analytical problem. Yet the increasing pressure to abate GHG emissions is forcing operators—especially large ones, given their huge carbon footprints—to seek solutions with urgency.

As oil and gas move through the supply chain, to refiners and final markets and combustion points, the resulting emissions become notoriously hard to measure. Companies typically rely on estimates of emissions from data reported by suppliers as well as estimates of end-user consumption patterns. But data quality tends to be poor, and companies often do not have the capability and resources to develop a true understanding of their scope 3 footprints. Moreover, there are no set industry standards for measuring and reporting on scope 3 emissions, making it difficult to compare scope 3 emissions footprints across operators or to set emissions targets on the basis of competitive benchmarks.

The sheer complexity of establishing a baseline for scope 3 emissions makes it essential to use AI-based tools. These tools can model the entire O&G value chain—from exploration and production to refining to distribution and, ultimately, customer usage—at a very granular level.

The sheer complexity of establishing a baseline for scope 3 emissions makes it essential to use AI-based tools.

Well location, for example, will determine in part the extent of the scope 3 emissions produced by suppliers and refineries as oil or gas is distributed to downstream refineries and pipelines. Further downstream, the model can follow the production of scope 3 emissions from the transportation of finished product by channel and by customer using transaction-level data from the business systems. The emissions footprint at the point of consumption can even be estimated by modeling fuel consumption patterns across geographies and industries.

With this baseline data in hand, companies can then use additional AI tools to work with suppliers and customers to assess the impact of specific decarbonization levers. Companies are using several levers to reduce their scope 3 emissions intensity. These include methods of reducing total net emissions—such as nature-based carbon capture, industrial sequestration, and carbon offsets—along with commercial partnerships and alliances across the value chain to promote direct reduction of scope 3 emissions. Further scope 3 reductions can be gained through asset portfolio optimization.

In short, the sheer amount of scope 3 emissions for which every O&G company is responsible makes it incumbent on them to turn to such tools as the basis for any abatement program.

Next Steps

O&G companies looking to jump-start their decarbonization efforts will need to take into account three key considerations across the abatement value chain.

Baselining. All too often, companies’ baselining efforts focus largely on emissions forecasting across scopes 1 and 2 in the context of compliance. Make sure the baselining process covers the full range of current operations across all assets and the entire value chain, including suppliers and customers, and that it takes into account production forecasts, information on cessation-of-production dates, and growth opportunities. And don’t let the baselining process overwhelm the actual abatement effort.

Abatement. The financial viability of abatement initiatives is rarely a barrier, especially in regions with high carbon prices or strong abatement incentives. Nevertheless, make sure that abatement efforts remain focused on finding win-win scenarios that take into account production improvements and the expected life of production assets. Abatement initiatives must be both economically sound and able to be carried out rapidly.

Governance and Change Management. With attention focused on new business opportunities, many companies struggle to properly manage their decarbonization efforts, link them clearly to overall strategy, and effectively mobilize their asset teams. Integrating digital abatement tools into the overall data architecture is key to create a single source of truth for production and financial data as well as decarbonization. This, in turn, can serve as the basis for the change management program needed to adapt the company’s operating model and to institute the cultural changes and new ways of working needed to enable faster decision making and speedy, effective carbon abatement.

The Abatement Advantage

Emissions abatement is fast becoming table stakes for O&G companies. The tools and techniques of AI and machine learning, therefore, must become central to the strategy of all companies in the industry looking to abate their GHG emissions across the board. The enormous number of variables involved in establishing emissions baselines, optimizing operations, and reporting accurately can be handled only with the help of these digital capabilities. Their value to the O&G industry in its efforts to combat global warming is incalculable.

Ultimately, far-sighted O&G players will also come to see emissions abatement as a competitive advantage. O&G customers working to reduce their own scope 2 emissions, for example, will likely turn to suppliers of oil and gas that can demonstrate abatement success. Technologies that enable them to do so will create a win-win for all concerned—not to mention benefit the planet as a whole.

The authors would like to thank Marie-Hélène Ben Samoun, Ferrante Benvenuti, Brendan Boyle, Thomas Giraud, Olivier Kahn, Prashant Mehrotra, and Ramya Sethurathinam for their contributions to this article.