Agile’s reach is broadening inside companies, but vendors are often left outside the new processes. A five-pronged approach allows agile and outsourcing to fuel each other—and expand the rewards.

As agile ways of working take hold, many companies are moving faster, launching better products, operating more efficiently—and mastering only half the equation. That’s because agile tends to have an internal focus: train employees, build a culture, manage change, reap the rewards. Yet most companies also rely on external providers— especially when it comes to digital transformation . By leaving vendors outside their agile processes , they’re leaving value on the table.

When agile meets outsourcing , the paradigms fuel each other. Companies can expand their agile teams—or ramp up new ones—more quickly. They gain access to specialized talent. They leverage the know-how of agile-savvy vendors. And all the while, they boost the quality of their outsourcing by focusing on outcomes rather than outputs.

Tying the knot between agile and outsourcing is no simple feat. Many companies have faced roadblocks, from finding the right mix of in-house and external resources to structuring deals so that vendors and companies share risk and can better measure—and improve—performance. But there’s an approach that can make the union work.

Tying the knot between agile and outsourcing is no simple feat.

Five Key Steps

Integrating agile and outsourcing is particularly important as companies embrace digital business models and customer-centric offerings. Agile is an essential pillar in digital transformation . So, too, is outsourcing. In a study by BCG and the University of Auckland, 100% of respondents said they leveraged external resources in their transformation. While some companies relied exclusively on third parties, the vast bulk—92%—used a mix of internal and third-party resources. Yet very few were able to create a sustainable model that aligned incentives between the parties.

Our approach helps companies develop that model—and a foundation for combining agile and outsourcing. It focuses on five pivotal stages in the outsourcing process: crafting a sourcing strategy for agile teams; selecting the vendor; negotiating and contracting; setting up ways of working together; and evaluating the partnership. What follows is a closer look at tackling—and mastering—each stage.

Crafting a Sourcing Strategy for Agile Teams

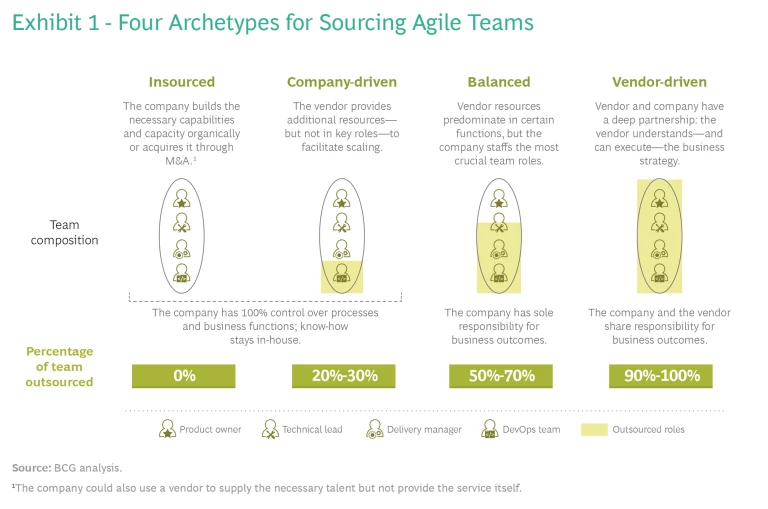

The cornerstone of agile is the cross-functional team. So not surprisingly, one of the first—and biggest—challenges in bringing vendors into agile is determining which functions to insource and which to outsource. To strike the right balance, companies need to understand the four main archetypes for sourcing agile teams. (See Exhibit 1.) They also need to assess priorities, capabilities, and tradeoffs.

The four archetypes break down as follows:

- Insourced. The company retains full control over processes, business functions, and know-how—and doesn’t outsource any part of the agile team.

- Company-driven. While the company still retains control over processes and business functions, and staffs key team roles, vendors provide additional resources to facilitate scaling. Typically, 20% to 30% of the team is outsourced.

- Balanced. Vendors have a much larger footprint—generally accounting for 50% to 70% of the team composition—but the company retains the most crucial roles, such as product owner and technical lead.

- Vendor-driven. Vendor and company share responsibility for business outcomes, with the vendor providing the bulk —if not all—of the agile team. In this model, the vendor has a deep understanding of the company’s business strategy . And it has the ability to carry it out.

Zeroing in on the right model is not a one-time event. Companies will need to perform the analysis for each agile team, since those teams and their circumstances will vary. But some key considerations can help guide the way.

Chief among them: the strategic importance of each team function. Some capabilities are so crucial to a company’s business or operating model that it’s preferable—even essential—to retain them. When a vendor controls such a function, companies can find themselves “locked in” with that vendor, no longer having the flexibility—or leverage—of switching providers relatively easily.

Some capabilities are so crucial to a company’s business or operating model that it’s preferable—even essential—to retain them.

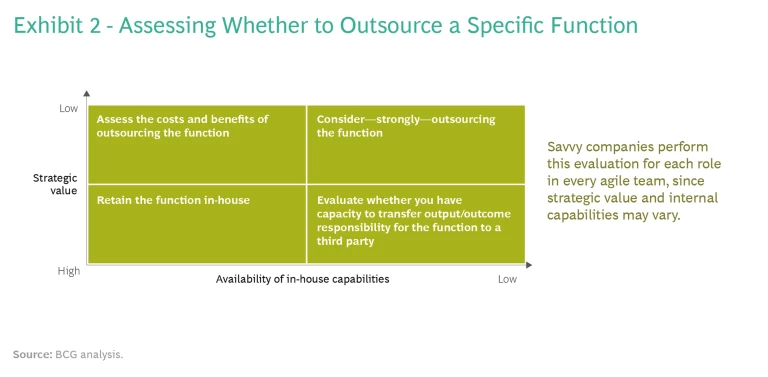

But there is also the question of availability: Does the necessary talent exist in the organization? If not, can it be generated fairly quickly? Some calls are easy. Companies should retain team functions they deem highly important and that are readily available and accessible in-house. Conversely, they should outsource low-importance functions that are not readily available and accessible in-house. But in between, the decisions are harder. (See Exhibit 2.) In these cases, considerations like cost and the vendor’s agile maturity level can tip the scales.

For many businesses, the company-driven model may be the most tempting. It offers a way to augment agile teams relatively quickly, while retaining key roles and know-how. And it gives flexibility. By keeping the most crucial roles in-house, companies can pivot to new vendors when necessary and maintain agile ways of working. In our own experience, this has been the most common model for mixing agile and outsourcing.

By letting an agile-savvy provider lead the charge, a company new to agile methodologies could reap benefits faster than if it started from scratch.

But keep in mind that the balanced and vendor-driven models have their advantages, too. By letting an agile-savvy provider lead the charge, a company new to agile methodologies could reap benefits faster than if it started from scratch. Similarly, companies that are well along their agile journey could learn from more-experienced vendors ways to shape and accelerate their own embrace of agile.

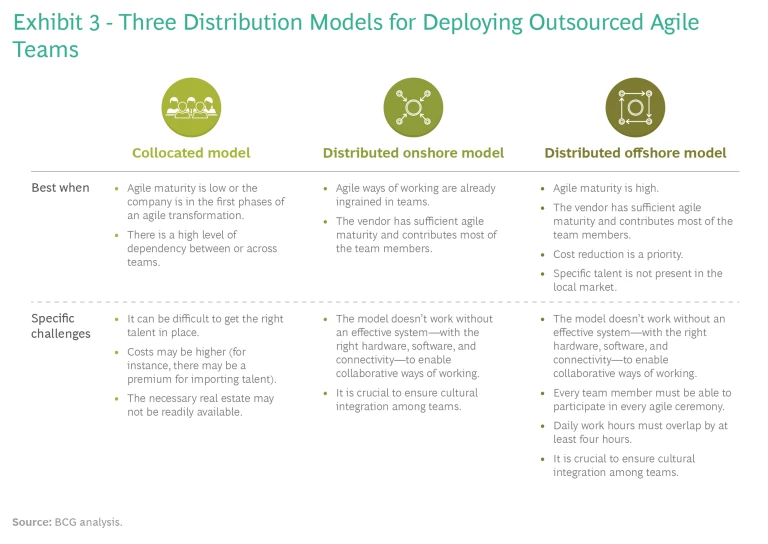

In honing a sourcing strategy, companies also need to determine the right distribution model. How physically close—or far-flung—should the team be? Here, there are three ways to go: a collocated model, where members work in proximity to one another; a distributed “onshore” model, where members typically work in the same time zone; and a distributed “offshore” model, where members are in different time zones. (See Exhibit 3.)

In making the decision, companies need to consider agile maturity—theirs as well as their vendor’s—along with costs, real estate availability, and access to talent (specialized skills won’t be equally available everywhere). They also need to assess the feasibility of integrating—both technically and culturally—distributed teams. That feasibility may be greater than you think: the pandemic has ushered in new ways of working that have shown that distributed models work.

Selecting the Vendor

Now, how to make the chosen sourcing and distribution models work? Selecting the right vendor is crucial, but traditional approaches might not cast a wide enough net—or ask the right questions.

Selecting the right vendor is crucial, but traditional approaches might not cast a wide enough net—or ask the right questions.

To be sure, many vendors have adopted—or can adapt to—agile ways of working. But in an increasingly digital world, it’s often nontraditional sources, such as innovation labs, startup incubators, universities, and niche players that can provide vital talent and capabilities. Companies need to adjust their sourcing processes so they consider new ecosystems and can identify and nurture potential partners.

This means applying a longer, but more flexible, screening checklist. While the usual criteria—vetting a provider’s financials, technical capabilities, IP protections, local resources, track record, and so on—are still important, some niche players might not pass traditional background checks. Yet they still might make for a good fit. So companies need to factor in additional criteria, such as: What is novel and potentially disruptive about this player? And then the company could opt occasionally (but judiciously) for a judgment call instead a rigid, no-exceptions policy when a contender can’t check a time-honored box.

Evaluate, too, a provider’s ability to adapt to agile. That analysis varies with the sourcing model. For instance, for the balanced archetype, companies should look closely at the provider’s agile maturity and whether it has the capability to transfer know-how through training, workshops, and other means. With the company-driven model, such factors are less critical. Yet for the vendor-driven model, where the provider is deeply involved in key functions and bears more responsibility for results, companies must go even further: checking that the vendor has sufficient business process knowledge and can commit to outcomes.

Negotiating and Contracting

Agile’s orientation around teams adds new wrinkles to how companies negotiate with their vendors. Savvy companies will seek a contract that recognizes and facilitates the hallmarks of successful agile teams. Such teams are empowered to make the decisions and take the actions that drive business outcomes. They’re also accountable for those outcomes. And successful teams are persistent, staying together for the long run, instead of disbanding after a specific project. This is important because it takes time for team members to get the “rhythm” of working together. By avoiding frequent swap outs, agile teams avert the need to repeat the learning curve.

Savvy companies will seek a contract that recognizes and facilitates the hallmarks of successful agile teams.

Companies, then, must come out of negotiations with three key boxes checked: they need to align incentives, ensure (as much as possible) that teams remain intact, and create a robust system for measuring performance.

Incentives. Traditionally, incentives are not well-aligned between company and vendor. Outsourcing often follows a time-plus-materials pricing model, which has its advantages but doesn’t give the vendor much skin in the game—or motivation for putting and keeping its best people on a given team. Even more important: the time-plus-materials model means more revenue for the vendor if the project grows in length or complexity. So vendors lack the incentive to push back on additional requirements—and to push for getting out a minimum viable product early.

Ideally, companies could tie 100% of the vendor’s earnings to business outcomes. But that’s rarely possible since few vendors have total control over the outcome. A more realistic solution, then, is a sliding scale: the more control the vendor has, the more that pricing is linked to outcomes.

Ideally, companies could tie 100% of the vendor’s earnings to business outcomes. But that’s rarely possible since few vendors have total control over the outcome.

Teams. As for keeping teams intact, specific contract clauses can help—but what clauses, exactly? Negotiations work best when both sides feel they’re gaining something. So companies shouldn’t be too draconian (vendors also need flexibility) or too relaxed (the team shouldn’t be the vendor’s training ground). In our experience, a good practice is to limit unwanted attrition to a predefined threshold, such as 20% each year, or to specify—by name—team members who cannot be moved unless the company asks for the change.

We have seen, too, a benefit when companies give themselves the option to internalize a certain percentage of vendor personnel each year (ideally, up to 20%). This helps a company retain key talent and face less disruption should it subsequently switch vendors.

Performance. Finally, when it comes to measuring performance, both sides should agree on the right KPIs or, more common in agile, objectives and key results (OKRs). Crucially, they should decide whether a metric looks at output (such as story points completed) or outcome (such as customer satisfaction score). A good rule of thumb: Where a vendor has responsibility for a specific process or task, it should commit to an outcome-based metric. Where it has less say in how a team works, an output-based metric is likely to be more appropriate.

Surveys can also be valuable, helping companies and vendors alike to gauge team sentiment and how well members are adapting to agile and to each other. Transparency is crucial, too. Everyone—from upper management to the people on the teams—should have access to the metrics that track performance.

Setting Up Ways of Working Together

From day one, team members that come from a vendor must work efficiently and as part of the team. But onboarding and cultural alignment can be particularly challenging, not only because team members come from different organizations but also because they might be located in different regions of the world.

The solution might seem obvious: treat internal and external people exactly the same. And, indeed, some practices are straightforward: everyone participates in the same agile ceremonies; everyone is evaluated according to the same metrics, shares the same perks, has the same learning opportunities, and can win the same awards (and rewards).

But some scenarios complicate the picture. What happens, for instance, if a vendor’s employees join an existing team? In that case, the product owner or scrum master should brief the new members on team rules and ceremonies. They should also schedule events to spark connections and collaboration.

And what if team members are geographically distant? Here companies must ensure that their processes and technologies—data access, connectivity, collaboration tools, and so on—truly bring everyone together. They should design events and ceremonies with virtual interaction (and time zones) in mind.

Likewise, an agile Center of Excellence (CoE) can help foster a team dynamic—and enhance transparency and communications—by providing simple but direct guidelines. An effective CoE gets everyone on the same page with respect to culture and agile ways of working.

Companies that get agile right also understand the value of robust governance. Typically, product owners and tribe leaders are the first line of defense, empowered to deal with most day-to-day roadblocks. That shouldn’t change when outsourcing is involved. But there are some new wrinkles. A team leader, for example, might need to coach or even remove a vendor resource—and should have the authority to do so.

A vendor management office (VMO) plays a key role in governance. It acts as a second line of defense, advising product owners and team leaders and acting quickly when roadblocks require escalation. A VMO reviews vendor performance against the defined KPIs and OKRs. And, when teams need help, it coordinates support.

Evaluating the Partnership

Because agile teams generally need several months to reach peak productivity, companies should let that window close before deciding whether their vendor is a keeper, a fixer-upper, or a goner. At its core, an evaluation is centered around two questions. How well has the vendor adapted to the desired agile ways of working? And: What are the results?

If a vendor has adapted well to agile and the results are good, a contract renewal is in order. Conversely, if the vendor hasn’t adapted well and the results are poor, it’s time to look for someone else. But things aren’t always so clear-cut.

What do you do, for instance, if your vendor has adapted well to agile yet the results are poor? It’s important to approach remediation together: company and vendor might codevelop a training plan for underperforming team members. And if adaptability is poor but the results good? Here, too, the key is formulating a joint approach: modifying incentives, investing in coaching and cultural alignment, or taking other steps.

If, ultimately, the solution is to switch gears—or providers—some best practices can minimize disruption. Include a contract clause, for example, that allows for increasing or decreasing vendor resources as needed. An insourcing clause is also valuable here, letting you bring in-house the team members who are working out, so when you switch to a new vendor you’re switching fewer team members—and getting back to peak productivity as soon as possible.

Companies have gained tremendous value from agile. And they’ve gained tremendous value from outsourcing. By bringing together the two paradigms, businesses can reap even greater rewards—particularly from their digital initiatives. That integration isn’t easy, but companies that approach the task in a savvy, holistic way may find that this is one instance where the whole might indeed be greater than the sum of the parts.