Climate change poses a significant threat to the continent. But as global decarbonization efforts intensify, Africa could emerge as a green powerhouse.

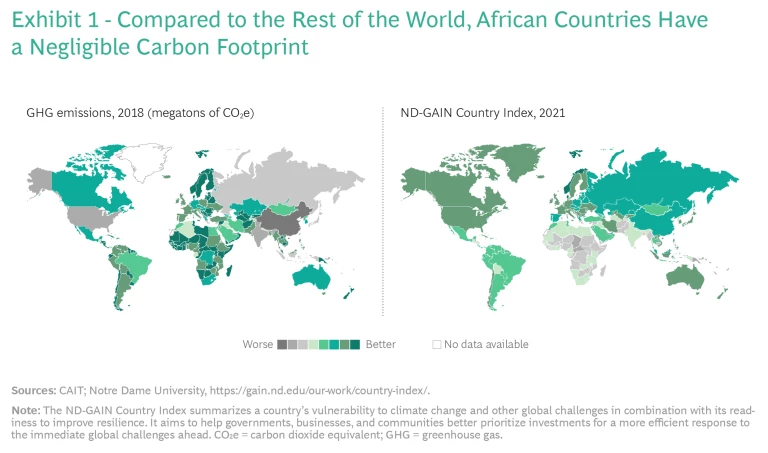

Of the six continents that have large human populations, Africa has contributed the least to climate change. In 2019, it drove only 4% of global CO2 emissions, and about three-quarters of that total came from just five countries—South Africa (33%), Egypt (17%), Algeria (12%), Nigeria (10%), and Morocco

Those dire outcomes, however, are not inevitable. African countries have a chance not only to create resilience for their economies and societies, but also to advance their industrial development. To avoid disastrous consequences and seize opportunities, African countries must prioritize three actions:

- Invest massively in climate adaptation. African countries need to mobilize massive funds to build climate resilience. Collaboration with and financial support from the international community will be critical to obtaining the necessary investment.

- Build the foundation for low-carbon socioeconomic development. By leveraging new technologies and business models, African countries can chart their own low-carbon development paths optimized to the local context.

- Accelerate the creation of local green manufacturing capabilities. African countries need to harness their natural resources and local capabilities to drive the creation of localized green manufacturing hubs. Doing so can create millions of jobs and spearhead Africa’s industrial development.

The success or failure of these efforts will hinge largely on the ability of African leaders and of the global community to work collaboratively on topics of finance, technology, and capacity building. African leaders must create sound plans for national climate resilience that identify solutions to their countries’ specific challenges and opportunities. At the same time, developed countries in other parts of the world that have historically contributed the most to global emissions must help unlock the required investments from the private and public sectors. One recent positive sign in this regard is an agreement announced at the November 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) that will support South Africa’s efforts to decarbonize its power sector and realize a just energy transition.

Committing to such collaborative efforts is not merely a matter of climate justice, ensuring that African countries that contributed little to climate change do not suffer the most from it. Rather, collaborative action by African countries and the international community can advance sustainable development, enable Africa to emerge stronger in the burgeoning net-zero economy, and drive progress in confronting the climate threat—not just for Africa, but for the planet as a whole.

The Climate Challenge in Africa

Africa’s contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions has been and remains negligible. Emissions per capita in sub-Saharan Africa are among the lowest in the world, at 0.8 megaton of CO2 per capita in 2018. The corresponding emissions figures in the United States and the European Union (EU) were roughly 15.2 and 6.4 megatons of CO2 per capita, respectively, in

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states that the rate of human-induced surface temperature increase on the African continent has been and will continue to be more rapid than the global average. Extreme weather events, including heavy rain and heat waves, will increase in frequency and intensity across the continent. Most of the continent is projected to experience drier conditions overall. Sea level rise will threaten Africa's coastal lines, including mega cities such as Lagos, Nigeria, which is built on a

The local impact of climate change in certain parts of Africa is likely to have disastrous consequences. The continent’s key economic sectors today—particularly its rain-fed agriculture—depend heavily on weather and are vulnerable to changes in weather patterns and local climates. Consequently, rising global temperatures could heighten food insecurity, drive population displacement, threaten human health, and intensify stress on water resources. At the same time, Africa has underdeveloped infrastructure, relatively little local capital, and endemic poverty, all of which severely limit the ability of countries in the region to adapt. The poverty challenge is particularly daunting: 33 of the 54 countries on the African continent fall into the category of least developed countries, meaning that they have low incomes, face severe structural impediments to sustainable development, and are particularly vulnerable to economic and environmental shocks. And roughly 40% of people in sub-Saharan Africa live in extreme poverty, subsisting on less than $1.90 per

African countries whose economies rely on exporting fossil fuels or carbon-intensive products will suffer an additional hit as the global economy decarbonizes. In 2018, fossil fuels accounted for almost 50% of all exports from sub-Saharan

Failing to adapt to both the physical risk of climate change and emerging trade risks could have devastating, long-lasting socioeconomic consequences.

Three Climate Action Priorities

The magnitude of the climate change challenge facing Africa requires countries to take three aggressive actions in response: invest massively in climate adaptation ; build the foundation for low-carbon socioeconomic development; and accelerate the creation of local, green manufacturing capabilities. As leaders inside and outside Africa develop strategies in each area, they must base their efforts on the core principle of ensuring a just transition that contributes to the improved well-being of citizens and to the eradication of poverty and inequality. (See “The Need for Just Transitions.”)

The Need for Just Transitions

Key decision makers in both the public and private sectors must thoroughly assess a number of important opportunities and challenges, as well as the enablers required to capture those opportunities, if they are to ensure a just transition of South Africa’s power and other sectors to net zero. (See the exhibit.) For each opportunity and challenge, the public and private sectors need to act collaboratively and decisively to ensure no one is left behind. A holistic solution encompassing a comprehensive set of enablers will be critical not just for South Africa but for Africa as a whole to ensure that no one is left behind and that the economy of the future is inclusive and robust.

Invest massively in climate adaptation. Across the continent, countries must drive the development of resilient agricultural systems, coastal infrastructure, cities, and water resources, while promoting the preservation of regional biodiversity and land. They should give special attention to protecting their most vulnerable communities, including those most likely to become climate refugees or to fall into extreme poverty traps. As countries focus on adaptation measures, they will also need to tailor their actions to the regional context.

The cost of adaptation measures in Africa will be immense. Even in a scenario in which the global average temperature increase by 2050 is limited to 2 Celsius degrees, the United Nations Environment Program estimates that the continent's adaptation costs will be approximately $35 billion a year by 2050 and $200 billion a year by the 2070s. In a scenario where temperatures increase by 3.5 to 4 Celsius degrees by 2050, adaptation costs in Africa could reach $45 billion to 50 billion a year by 2050 and up to $350 billion a year by the

African governments are already investing in adaptation projects and activities. Examples include the Great Green Wall, which aims to restore degraded land across the Sahel region; adoption of micro-irrigation practices in Morocco’s agricultural sector; a movement toward more resilient crops in Egypt; reforestation efforts in Central and East Africa; deployment of water desalination projects across the continent; and initiatives such as the Initiative for the Adaptation of African Agriculture, which is led by Morocco and supported by a large coalition of regional and international public- and private-sector stakeholders. New tools, particularly advanced analytics, will provide crucial support for adaptation action in the region. (See “The Power of Advanced Analytics in Adaptation.”)

The Power of Advanced Analytics in Adaptation

Take drought prediction, for example. In East African countries such as Kenya, successive years of poor rain have left the region in severe drought, jeopardizing food security for millions of people. Drought prediction tools have been developed that draw on advanced analytics to improve resilience in the face of such events. These tools have the potential to serve as early warning systems, pinpointing areas that are at high risk of droughts or floods. They can support targeted responses by assessing at a very granular level the impact of climate change locally on specific sectors, regions, or populations, and they can support decision making by testing the macroeconomic and microeconomic effectiveness of potential measures and policies. Such tools are invaluable to policymakers seeking to anticipate and respond to droughts, as well as to donors wishing to maximize the positive impact of their funding.

Creating and effectively leveraging data analytics tools will be critical to successfully driving short- and long-term responses to climate change.

Post-COVID-19 recovery measures can be another powerful lever in driving climate action in Africa. In the East African Community (EAC)—consisting of the nations of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda—such measures include efforts to improve adaptation in the agricultural sectors by building climate resilience, ensuring food security , and bolstering value creation by shifting to the production and export of higher-value crops. To improve agricultural adaptation, EAC countries are taking steps to enhance agrobiodiversity, diversify food sources, and promote climate-smart agricultural production, including regenerative practices and community-led localized solutions. These steps can yield meaningful environmental, social, and economic benefits. For example, climate-smart agricultural practices in the EAC could lower greenhouse gas emissions by up to 1%, reduce crop loss by 2% (350 kilotons), reduce water use by 1% (roughly 90 cubic meters per hectare) as a result of planting heat- and drought-tolerant crops, increase the yields of nutrient-dense crops, and reduce undernourishment in the population. All told, the production of high-value crops through these practices could bolster annual GDP for the EAC region by as much as $2 billion.

Despite important moves such as those that the EAC is making, adaptation measures to date are insufficient. In large part, that is because most African countries lack the financial resources to fund such efforts and because access to global finance is inadequate. Although Africa is the world’s second-largest and second-most-populous continent, only 10% of the world’s climate funds go to the continent, and globally less than 15% of all climate funds go to adaptation

Build the foundation for low-carbon socioeconomic development. If African countries are to increase their adaptive capacity to deal with climate change, they must advance their overall socioeconomic development—and access to

clean energy

will be critical to this effort. Unfortunately, a significant energy gap persists on the continent today, with roughly 600 million Africans lacking access to

Climate change and the pressure to close the development gap have put African countries at a crossroads. Some observers argue that Africa should pursue a development path similar to the one that today's industrialized countries did in the past, rooted in fossil fuels and outdated technologies. But this "grow first, clean up later" approach would lead African countries to create highly carbon-intensive economies and lock the continent into increasingly uncompetitive socioeconomic and technical systems. Ultimately, such a bet would limit Africa’s growth potential, make it a “market of last resort” that relied on outdated technologies, and further widen the development gap between it and the rest of the world.

African countries should avoid repeating the unsustainable development choices of the past century. Instead, they should leverage the continent’s vast renewable resources and existing and emerging disruptive clean-energy technologies—including renewable energy, green hydrogen, green synthetic fuels, advanced battery technology, and digitization. Such efforts not only would help address the challenge of energy-related emissions, but also would improve the availability, reliability, and affordability of Africa’s energy supply and promote robust socioeconomic development.

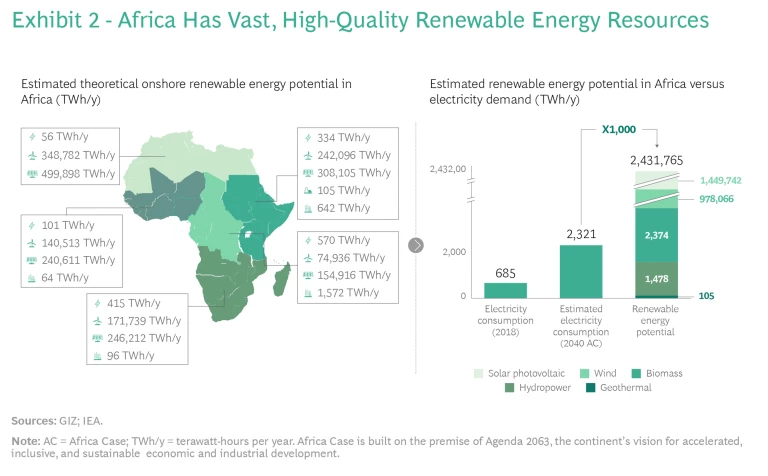

Many African countries are endowed with high-quality renewable energy resources. (See Exhibit 2.) Seven of the ten sunniest countries in the world are in Africa. In fact, the continent could become the first to power industrialization predominantly through locally available renewable energy sources. Critically, the intermittent nature of renewables can be managed by deploying hydropower (where locally feasible), natural gas (which is available in a number of African countries and can serve as a transition fuel in the middle term), and, in the longer term, green hydrogen and advanced battery technology. Morocco has already begun to make the transition to a predominately renewable-energy power system. The country aims to meet 52% of its power demand via hydro power, wind, and solar by 2030, and potentially to export solar-generated electricity to less-sunny Europe in the longer term.

To grasp the potential of renewable energy in Africa to help solve the continent’s energy gap and drive decarbonization, consider the situations of the EAC, Nigeria, and South Africa.

In the EAC, where around 140 million people have no access to electricity, distributed renewable energy is the most cost-competitive

In Nigeria, meanwhile, distributed solar photovoltaic (PV) energy is the most cost competitive option to meet the electricity supply gap in urban areas, such as the city of Lagos, which faces a significant grid supply gap. In 2020, that gap was roughly 29 TWh, with the grid supplying only 3% to 5% of demand. Solar PV systems, such as micro solar home systems, standalone rooftop systems, and solar diesel hybrid systems, could generate up 10 to 15 TWh a year in Lagos.

One of the most carbon-intensive economies in the world, and the largest emitter on the continent, South Africa is responsible for more than 30% of Africa's emissions, and its coal-based power sector drives 43% of its emissions . At the same time, however, South Africa has among the best wind and solar resources in the world. A renewables-dominated power system, backed by natural gas as a transition fuel for periods of peak demand, is the most cost-competitive power system for the country.

Of course, transitioning South Africa’s power system to net zero will not come cheap. It will require the deployment of roughly 150 gigawatts of wind and solar capacity by 2050—almost four times the total installed capacity of South Africa’s coal power plants today—and a total investment of about $200 billion. International support for such an effort is growing. At COP26, the governments of South Africa, France, Germany, the UK, the US, and the European Union announced an agreement to provide $8.5 billion over the next three to five years to help support South Africa’s transition. If well managed and well coordinated, the transformation of South Africa’s power system by 2050 could create roughly 3.5 million net job years, assuming that the country can effectively reskill and redeploy the workforce, with additional job potential if the country can localize elements of the renewable energy value chain.

Ultimately, the pursuit of low-carbon development paths by South Africa and other African countries will benefit those living on the continent and will be a critical factor in mitigating climate change globally.

Accelerate the creation of local, green manufacturing capabilities. In addition to holding high-quality renewable energy resources, Africa boasts vast deposits of minerals such as manganese, lithium, and cobalt. These inputs can help fuel the development of a robust green manufacturing base .

For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo has the largest proven reserves of cobalt and accounts for 70% of global cobalt production today. African countries can harness these natural resources and locally available renewable energy to establish globally competitive production of energy-intensive, climate-compatible industrial goods such as green steel and other green metals, fuel cells, electric vehicles, and green-hydrogen-based chemicals and fuels. (See “The Green Hydrogen Opportunity in Africa.”)

The Green Hydrogen Opportunity in Africa

A key element in low-cost green hydrogen production will be the availability of sufficient high-quality renewable energy resources. Countries that are rich in renewable energy, such as Australia, Chile, and Saudi Arabia, are already positioning themselves to become leading suppliers of hydrogen products.

However, many African countries are endowed with vast renewable energy resources of their own and could produce green hydrogen at globally competitive prices. For example, South Africa could generate green hydrogen at a levelized cost of roughly $1.6 per kilogram by 2030, making it competitive with the corresponding 2030 levelized costs in Australia (about $1.6 per kilogram) and in Saudi Arabia (about $1.5 per kilogram). Leveraging its existing expertise in synthetic fuel production, South Africa is well positioned to become a major producer of green fuels, such as synthetic aviation fuel and e-ammonia, for local and global markets.

The continent’s unique natural capital gives it another significant green opportunity. Voluntary carbon markets are growing quickly, reflecting the increased need for nature-based carbon sinks such as forest preservation, soil restoration, and biochar production. As a result, African countries can develop new businesses and services that are good for the planet even as they generate new profit pools for the continent.

The Congo Basin rainforest, for example, is the world’s most important forest ecosystem after the Amazon forest. The ecosystem is valuable both for biodiversity and for carbon sequestration. Gabon, which today relies heavily on oil imports, is exploring how to monetize the preservation and restoration of its portion of the Congo Basin forest—an ecosystem that absorbs around 140 megatons of CO2 annually, more than one-third of France's annual

Driving Global Collaboration

To ensure that they realize their green potential, African countries must drive collaboration on national, regional, and international levels and across sectors. This will involve stepping up and taking proactive measures. The critical starting point is to develop ambitious national climate resilience plans that foster concrete adaptation strategies, establish regional and international collaboration, and attract required investments. Such national plans should include three key components:

- Estimate the local impact of climate change using advanced analytics and other fit-for-purpose tools. These estimates can help countries identify adaptation requirements, define project pipelines for building climate resilience, and gauge potential socioeconomic impacts on the most vulnerable populations and the investments required to avoid or minimize detrimental effects over the coming years.

- Identify key policy enablers, develop supportive policy frameworks, and improve governance systems. The goal of these actions is to mitigate political and regulatory risk and ensure proper execution and tracking of climate-related initiatives. For example, countries must find the right balance between policies that phase out fossil fuels and those that encourage investments in new green technologies. The ability of African governments to address their future policy direction with a unified voice will be critical to creating transparency and improving investor confidence.

- Develop and implement regional, international and cross-sectoral collaboration strategies that strengthen the continent's seat at the global table. These strategies will be critical to capturing green opportunities—in particular, a substantial share of international financing—and driving stronger representation at international climate negotiations through a unified African voice. African countries must also align their approaches to engaging the international community on topics such as green finance, climate funding, technology transfer, and capacity building. The Initiative for the Adaptation of African Agriculture , which aims to attract more funds to Africa’s agricultural adaptation projects, offers a good example of how a coordinated alliance between multiple African governments can elevate key issues on the international political agenda. Such coordination can ultimately strengthen the continent’s negotiating position at key forums such as COP26 and beyond.

Climate change threatens to cause disastrous damage to African countries, even though they have contributed relatively little to climate change. This potential harm, in turn, poses a significant risk for the rest of the world. It is essential for African nations and for the international community, especially the developed countries that are mainly responsible for the climate crisis, to work together to counter the threat. They must jointly assess risks, identify suitable adaptation measures, and put them in place along with the required technological, financial, and political enablers.

At the same time, African countries need to identify and realize new green industrialization opportunities—particularly in connection with developing African manufacturing hubs for future local and global net-zero markets—to drive socioeconomic development on the continent. In this regard, Africa has the opportunity to turn vulnerability into strength and to grow into a green superpower, providing a firm foundation for sustainable development on the continent and beyond.

Achieving a climate-resilient, socially just, decarbonized future for African countries is critical not just for the continent’s political, economic, and environmental stability, but for the good of the world as a whole. It is clearly in the interest of governments around the globe to unlock massive investments in Africa and to partner with African countries to ensure that their efforts do not fail.