Current efforts to combat climate change leave women behind. But drawing women fully into the fight is a win-win—accelerating climate progress and advancing gender equity.

It is no secret that climate change is likely to have a disproportionate impact on women. For example, women are more at risk in climate-induced disasters. Research also suggests that women’s livelihoods and education will take a harder hit than men’s as the planet warms. Less widely recognized, however, is the fact that the current approach to combating climate change could leave women behind, too.

If current trends in areas such as education and employment continue, BCG analysis indicates, climate mitigation and adaptation strategies as designed today could delay the attainment of gender equity by 15 to 20 years. This is largely because women are underrepresented in the fast-growth green economy and therefore are at a disadvantage in garnering new jobs, participating in reskilling, and gaining access to funding for green tech startups.

The good news is that this outcome is not inevitable. Applying a gender lens to climate action will not only address the inequity issue, but also accelerate progress in mitigating climate change and adapting to it. We do not have to decide which pressing challenge to address and which to ignore. Rather, with the right approach, moves to combat one can fuel progress in the other.

On the basis of our work with private- and public-sector organizations to drive progress on climate and gender equity, we see two primary areas for action:

- Embed a gender lens in climate investments. We expect global investment in efforts to achieve net zero to total $100 trillion to $150 trillion by 2050. Players in the public, private, and social sectors should work to ensure that women participate fully in that effort, including by supporting female entrepreneurs in the green economy.

- Ensure equity in green economy jobs. Governments and companies must take steps to increase the share of women who are educated and trained in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and sustainability-related fields, and they must ensure equal representation of women in reskilling efforts in major sectors of the global economy.

Concerted action in both areas will create a win-win—advancing gender equity and accelerating the global effort to reach net zero.

The Unintended Consequences of Climate Action

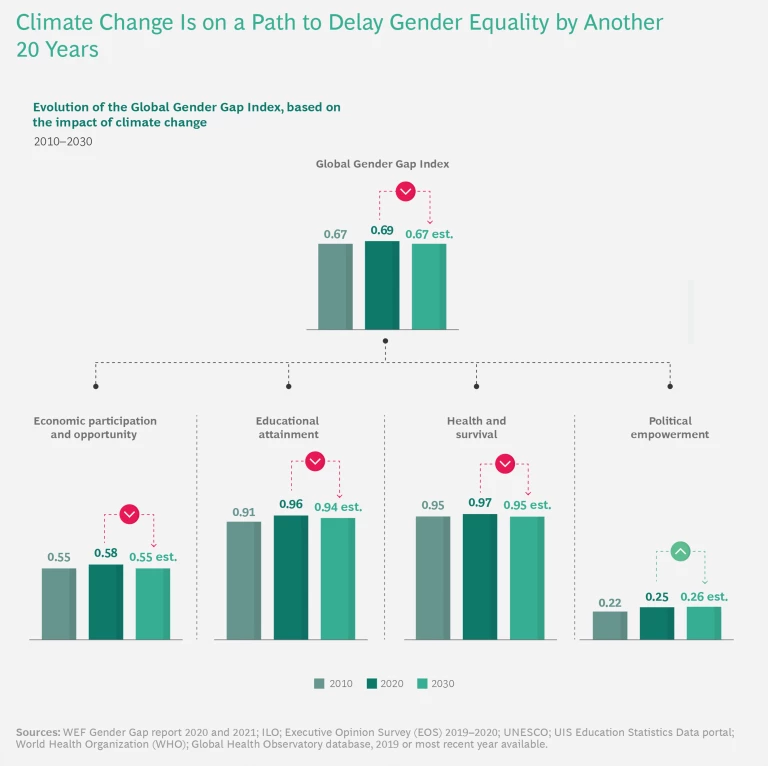

To understand the impact of climate action on gender equality we use the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Gender Gap Index. This instrument measures the gap as an index (ranging from 0 to 1), with 0 representing complete inequity and 1 representing parity between men and women. The index has four dimensions: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. In view of the current level of progress and the recent outsize negative impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on women, the WEF estimates that it will take roughly 135 years to close the global gender gap. The actual duration of the gap is difficult to project with precision, but evidence indicates that it is likely to persist for a significant period of time.

As numerous studies and reports have detailed, climate change alone could extend that period further. That’s because women are likely to face reduced access to education and employment and to experience greater negative health and safety impacts from climate-induced natural disasters. BCG estimates that climate change could reverse gender progress and push the attainment of gender equity out another 20 years. In other words, if the impact of climate change on women goes unaddressed, gender equity in 2030 will be back to where it was in 2010. (See “Quantifying the Impact of a Warming Planet on Gender Equity.”)

Quantifying the Impact of a Warming Planet on Gender Equity

First, women’s employment and income levels will likely take a bigger hit than those of men. Consider agriculture. Overall, women depend more on the agricultural sector than men do. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, more than 60% of women work in

Second, women’s access to education is likely to be impacted. Plan International has observed that a climate-induced crisis such as a drought often results in curtailment of girls’ education, as “families may no longer be able to pay school fees, or girls may need to travel further for water and firewood, leaving no time for their

Third, we project that life expectancy for women will likely decline more than that of men as a result of the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases and injuries. Research has found that women are often at greater risk from natural disasters. For example, about 80% of the victims of the Sidr cyclone in Bangladesh were women and girls. And in 2008, when cyclone Nargis devastated Myanmar, 61% of the victims were

Our projections do include one bright spot, however: a slight improvement in the political empowerment component of the index. Over the past decade, women have been taking a larger role in addressing climate change, and this has expanded their overall influence in the political sphere. In the years ahead, they will likely build on these gains.

Less appreciated, however, is how climate action as currently designed will impact women.

Positive Impacts of Climate Action on Gender Equality

Climate action will benefit the global population generally and women specifically in many ways.

Today, some diseases related to climate change—in particular, illnesses stemming from air pollution such as respiratory diseases— disproportionately impact women. Consequently, women will see an outsize benefit from environmental

Additional positive gender equity impacts are likely to stem from investments in measures that enhance society’s ability to adapt to climate change. These adaptation measures—including the use of climate-smart agricultural practices (low-till farming for example) and expanded access to microfinance for smallholder farmers—can positively affect women’s livelihoods. Consider the benefits of agroforestry practices, which involve incorporating trees and shrubs in cropland. The approach offers a low-cost way to restore soil fertility and could significantly boost female farmers, many of whom have difficulty affording inputs such as fertilizers. In addition, organizations such as the ECOWAS Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency have undertaken efforts to help rural women and girls gain access to burgeoning sources of renewable energy.

Negative Impacts of Climate Action on Gender Equality

Our research also found that climate action as designed today could have a negative impact on women in two critical areas—economic participation and opportunity and educational attainment—more than offsetting the positive effects outlined above.

Economic Participation and Opportunity. The negative impact in this area stems largely from the way climate action is likely to shape women’s access to jobs and reskilling in the green economy:

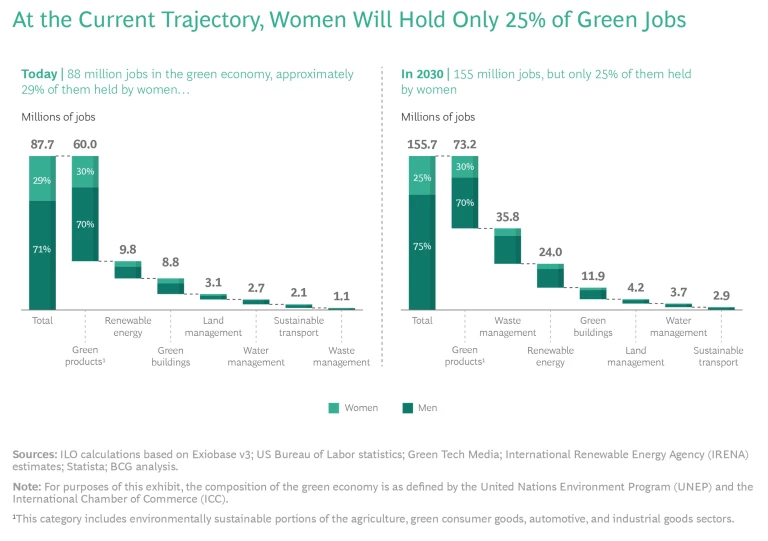

- New Green Jobs. The green economy comprises sectors such as green products (including agriculture, green consumer goods, and the green segments in automotive and industrial goods), waste management, and renewable energy. The green economy will be responsible for 67 million new jobs by 2030, according to BCG analysis. But the current gender distribution in the sectors where most jobs will be added suggests that women will hold only 25% of those new jobs. (See the exhibit.)

- Reskilling. According to the International Labor Organization, the transition to energy sustainability will require reskilling workers for 20 million new jobs by

2030.2 2 https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_732214.pdf, page 22. Women are underrepresented today in sectors where major green reskilling efforts will take place, such as energy (where women account for just 23% of the workforce), building and materials (31%), industrial goods (21%), and engineering (25%). For example, 6 million jobs will be reskilled in the oil and gas segment of the energy sector, but only 22% of reskilled workers will bewomen.3 3 https://www.ilo.org/inform/online-information-resources/research-guides/economic-and-social-sectors/energy-mining/oil-gas-production/lang--en/index.htm; https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-energy-gas-mining-oil/.

Factoring in the impact on women’s participation in green jobs and reskilling, we project that women’s labor force participation globally will probably decline and wage inequality will increase as women are relegated to lower-skilled jobs. That could translate into a 3-percentage-point decrease in women’s economic participation and opportunity by 2030.

Another major economic challenge that women face involves overcoming barriers to financing and opportunity in the green startup space. Between 2013 and 2019, venture capital funding in the climate sector—including innovative areas such as regenerative agriculture analytics and negative carbon technologies—increased by 84% on a compound annual basis and reached $16.3 billion in 2019, triple the value of the hot fintech

Educational Attainment. The second critical area where women are likely to suffer negative impacts from climate action is in access to vocational education. As the green economy booms, it will change the job market and make reskilling more important. But because women carry an outsize share of childcare responsibilities globally, they will find it difficult to participate in the vocational training system to the same degree as men. As a result, we project a 1% decrease in women’s educational attainment by 2030.

The Bottom Line. The erosion of gender equity as a result of reductions in women’s economic participation and opportunity and in their educational attainment is likely to more than offset women’s projected gains in health and survival and political empowerment. Absent a concerted effort to shift course and integrate women into climate action, progress toward gender equality will likely be delayed by an additional 15 to 20 years. This outcome is hardly fixed, of course, as there is still time to bring a gender focus to climate action.

The Win-Win of Bringing Women into the Climate Fight

Integrating women into the climate fight is a win-win. In addition to addressing issues of inequity, it will accelerate action on mitigating and adapting to climate change overall. A deep dive into two areas—agriculture, and STEM and green entrepreneurship—will help clarify why this is so.

Agriculture. Agriculture was responsible for 12% of total global greenhouse gas emissions in 2018, making it the second-largest contributor, after the energy sector, according to Climate Watch. Because women account for 43% of ag workers, their actions can have a meaningful impact on emissions in that sector. Mounting evidence indicates that women are inclined to adopt sustainable farming practices that can help in mitigating and adapting to climate change. For example, a study by the World Bank found that women in agriculture consistently seek new or alternative sources of water and plant new varieties of crops, and that their involvement in group decisions results in improved sustainable land management.

Investing in female ag workers and farmers through financing, reskilling, and access to land and insurance could lead to significant reductions in agriculture emissions. If women had the same level of access to support in those areas that men do—which we estimate would require global investment of roughly $35 billion—the result would be a cumulative emissions reduction from 2020 through 2050 of about 27.5 gigatons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e). That’s nearly 1 gigaton per year, which is approximately the amount of current total annual global emissions from the aviation industry.

Critical Sectors of the Green Economy. Investing in women’s STEM skills and green entrepreneurship can have a major impact as well. Today, women account for only 36% of STEM students worldwide. If women participated in STEM fields at the same level as men, the green economy—including startups—would see an infusion of engineers and creative talent. And assuming that those additional women-led startups contributed to emission reductions in line with climate startups historically, that could yield a total reduction from 2020 through 2050 of 12.7 gigatons of CO2e, or roughly 0.5 gigaton annually. The projected effect would be more significant in developed countries, where the green economy is already expanding at a rapid clip, but it could also have a major impact on the green economy workforce of emerging countries in the medium to long term.

Expanding women’s participation in other sectors of the green economy is likely to support emissions reductions there, too. For example, many companies are developing new sustainable business models as they race toward net zero. Consumer companies are remaking their businesses to offer more-sustainable foods, including plant-based proteins . Home goods companies are adopting circular business models to reduce emissions and environmental impact. And grocery retailers are trying to reduce emissions in the agricultural value chain, including by slashing food waste . Neglecting to fully engage women in these areas leaves a lot of talent on the bench and makes overall success more difficult.

A Sizable Impact. Taking action in agriculture and in STEM and green entrepreneurship could reduce global emissions by 1.5 gigatons annually—an amount equal to the combined total annual emissions of Indonesia, South Africa, and Brazil. And BCG analysis indicates that these steps would also likely bolster global GDP by nearly 2%. (See “The Economic Rewards of Gender-Inclusive Climate Action.”)

The Economic Rewards of Gender-Inclusive Climate Action

First, investing in women farmers could significantly increase yields productivity, mainly in middle- to low-income countries. Empowering women farmers broadly—not only through training in regenerative agriculture, but also through greater access to capital and equipment—will increase crop yields. The UN estimates that doing so could generate an additional $100 million in Malawi, $105 million in Tanzania, and $67 million in Uganda in annual agricultural GDP. And in India alone, the increase in productivity could translate into a boost of roughly $30 billion in annual GDP. Altogether, we project that support for women farmers could generate $700 billion to $800 billion in GDP globally by 2030, roughly twice the annual GDP of Nigeria.

Second, investing in closing the gender gap in green entrepreneurship to raise women’s overall level of entrepreneurial activity will creates jobs—roughly six jobs for every new venture. Research by Mass Challenge and BCG concluded that startups founded or cofounded by women performed better over time than those founded by men alone, generating 10% more cumulative revenue over a five-year period. Taking both those factors into account, BCG estimates that bolstering female entrepreneurs in green tech would add $500 billion to $600 billion to global GDP annually by 2030.

Third, investing in women in agriculture and green entrepreneurship has significant positive ripple effects. According to the Clinton Global Initiative, women invest 90% of their income back into their families, compared with 35% for men. Consequently, raising the overall level of female employment and reducing income inequality between women and men will not only reduce overall income inequality, but also generate an additional $200 billion in annual global GDP.

That economic boost doesn’t take into account the positive impact of other steps to integrate women into climate action, some of which are difficult to quantify. Consider steps to expand climate education and awareness for mothers. As mothers and educators, women are at the forefront of climate education, raising awareness and climate literacy within their families and communities. Indeed, statistics show that women in regions subject to droughts and floods teach their children how to adapt their behaviors and consumption patterns—for example, by reducing the amount of plastic waste they send to

Bringing a Gender Lens to Climate Action

Concerted efforts across the public, private, and social sectors are necessary to avoid unintended negative consequences of climate action on gender equality. Such efforts must also address the inequities that climate change on its own will bring. For example, governments, NGOs, and private companies should continue their support of women smallholder farmers—in particular, female-headed households—to ensure that they have appropriate tools and techniques, including access to regenerative agriculture practices, to sustain crop yields.

As climate action momentum builds, leaders in the climate fight must take steps to ensure that their plans fully take into account the impact of climate policies on women. We see two critical areas for action in this regard.

Embed a gender lens in climate investments. All players in climate policy, as well as private-sector actors, should take steps to ensure that women participate fully in the multi-trillion-dollar opportunity to achieve net zero.

A critical part of that effort involves supporting female entrepreneurs. Funding remains a key hurdle, and action to expand access to capital for women entrepreneurs in the green economy is vital. But other forms of support are equally important and often overlooked. Although the entrepreneurship gap has many causes—including differences in access to human capital, social capital, and ongoing financial resources—recent BCG research has found that one key factor is women’s relatively limited access to robust support networks . Investors, corporate executives, and public-sector actors should help scale female entrepreneurs’ networks to achieve sustainable impact. The African Women in Business Initiative, for example, supports and enables women entrepreneurs, in part by helping them cultivate professional networks.

Ensure equity in green economy jobs. If women are to participate fully in the green economy, all concerned parties must intensify their efforts to get more women into STEM education and jobs. Governments should establish targets for the share of women in STEM programs at both the regional level and the country level and should dedicate budgets to achieve these goals.

But employment opportunities related to climate action go well beyond engineering and other STEM disciplines. As companies drive transformations and business model innovation in support of net-zero goals, they will need sustainability expertise across multiple functions—management, operations, finance, and marketing. Higher-education institutions and corporations can ensure that female students and employees receive equal opportunity for training and reskilling in sustainability so that they can participate equally in these emerging employment opportunities.

Governments and companies should also dedicate more resources specifically to women’s reskilling, especially in sectors where women are underrepresented.

As currently structured, climate action poses a significant challenge for women. But it also represents an opportunity. Bringing women fully into the climate fight can reverse the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equity and can accelerate progress overall. To do that, policymakers engaged in crafting plans to combat climate change must apply a gender lens to everything they do. And those working to advance gender equity must increase their focus on helping women become players in the burgeoning green economy. Such action can create a much-needed win-win that advances both climate action and gender equity.

The authors would like to acknowledge Sander Van Damme for his support in the development of this publication.