One might assume that the world is awash in frugal buyers. Why wouldn’t it be? With most of the global economy struggling to recover from the COVID-19 crisis, one would expect households to be tightening their budgets. Indeed, in the major markets we have studied, in rich and poor nations alike, anywhere from 70% to 90% of consumers identify themselves as “value conscious.”

But how thrifty are consumers when faced with an actual buying decision? In particular, how attentive are they to the price tag? And are they always likely to go for the cheapest option or only under certain circumstances?

To answer these questions, BCG’s Center for Customer Insights interviewed 40,000 consumers around the world to learn more about what drives their choices at the time of purchase—and at the time a product is being used—in different markets and categories. Among our key findings: it could be a serious mistake to base global pricing strategies on the assumption that “value consciousness” is an overarching preference among consumers.

To get pricing right, brands need a much more nuanced understanding of how purchasing decisions are made in different markets and categories.

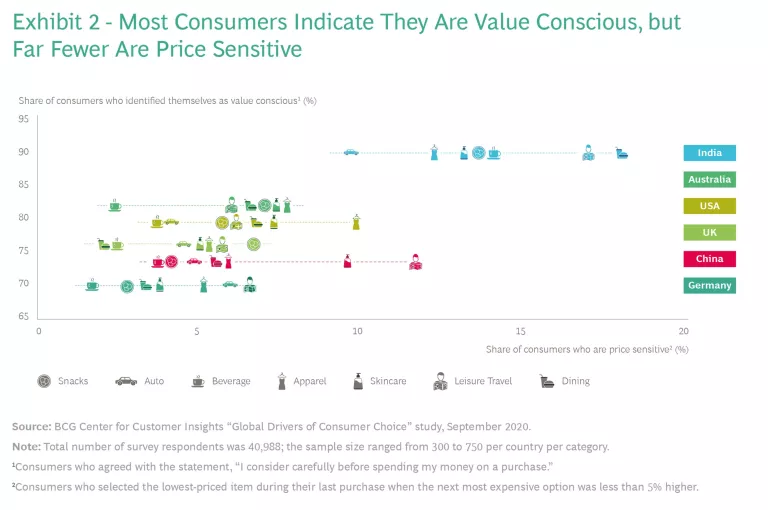

When we asked consumers about their most recent purchase in a wide range of consumer goods and services, a surprisingly small portion actually selected the lowest priced item. In fact, we found hardly any correlation between “value consciousness”—in other words, a preference for lower price as an attitude—and consumers’ actual purchasing behavior. And this was true across virtually every market and demographic group.

Our research produced several other valuable insights, including:

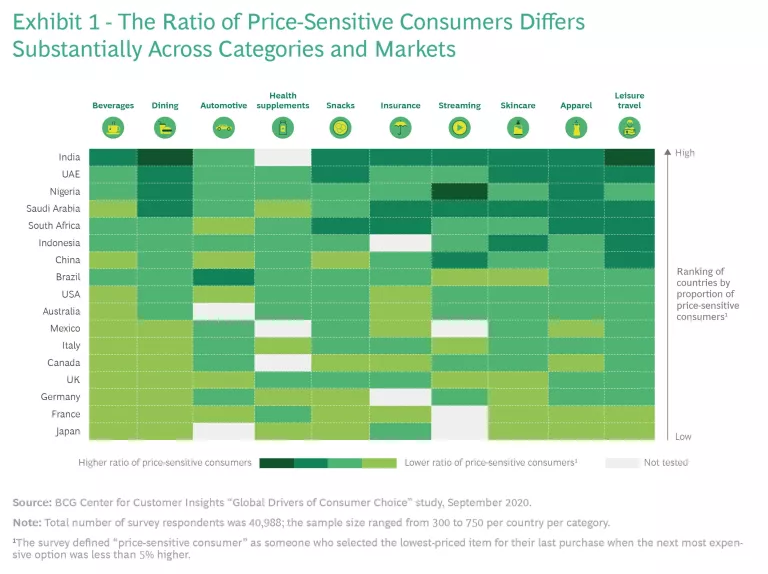

- The proportion of price-sensitive consumers varies widely from one market and product category to the next.

- In emerging markets, the proportion of price-sensitive consumers isn’t necessarily higher than in wealthy markets. The average Saudi Arabian consumer is more likely than Brazilians or Chinese to choose the lowest-priced option in most categories we studied, for example.

- The context in which a product is purchased is one of the most powerful drivers of price sensitivity. For instance, consumers in the US and Australia may be more price sensitive when dining with kids than when they are dining out as a couple.

These findings imply that brands shouldn’t define pricing strategies based only on stated consumer mindsets, such as value consciousness. Another key takeaway is that brands need a much more nuanced understanding of how purchasing decisions are made in different markets and categories, as opposed to applying a global playbook. Getting pricing right is critically important; it can be the difference between winning in the market with a differentiated value proposition and unnecessarily sacrificing profitability—or even triggering a self-defeating price war.

Understanding Price Sensitivity Around the World

The rise of the value-conscious consumer has been a widely acknowledged phenomenon ever since the Great Recession of 2008, with large percentages of households trading down to lower-value options in many product categories. We also observed a similar trend during the COVID-19 pandemic among lower- and middle-income consumers.

Pricing is a powerful tool for wooing such consumers, and many brands have concluded they can gain a competitive edge by offering the lowest prices on the market. But our research found that a bargain price usually doesn’t trump all other factors when it comes time for consumers to make a purchase. And it’s not safe to assume that consumers around the world, and in certain income and demographic groups, respond the same way to price.

In our interviews with consumers, we asked about their attitudes toward value consciousness and how price influences their purchasing decisions in ten categories of consumer goods and services. The study, part of our research into the attitudinal, demographic, and contextual drivers of global consumer choice, covered the following 18 markets: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, the United Arab Emirates, the UK, and the US. While other research has gone deeper into the influence of price on purchasing decisions, this is the first time we have covered such a breadth of markets across different categories.

For the purposes of the study, we used a narrow and rather strict definition of a price-sensitive consumer: a person who buys the lowest-price option, even when comparable products are available for a price difference of less than 5%. We chose to include only markets where a wide variety of product choices are available, so that the price ladder is rich enough to permit choice between similarly priced products.

The Share of Price-Sensitive Consumers Varies Widely

We found significant differences in the share of price-sensitive buyers, as per our definition, across markets and product categories. (See Exhibit 1.) Japan and France have the lowest proportion of price-sensitive consumers, while India has the greatest proportion across categories. (This does not rule out the possibility that lower-income consumers in Japan and France are not highly sensitive to price; further research is required.)

Surprisingly, though, we found little overall correlation between national income levels and the share of consumers with a preference for the lowest price. The UAE, with a per-capita income of around $70,000, has the second highest ratio of price-sensitive consumers; Saudi Arabia, with a per-capita income of $90,000, ranks fourth. Middle-income Mexico, meanwhile, has generally a lower ratio of price-sensitive consumers than the US and Australia. The assumption that lower-income countries necessarily have a higher share of price-sensitive consumers therefore appears to be untrue.

Surprisingly, there was not much correlation between national income levels and consumers’ price sensitivity.

The ratio of price-sensitive consumers also varies by category. The lowest price is most likely to sway consumers when they are shopping for leisure travel; that’s because consumers are accustomed to finding the best bargains by directly comparing prices for air tickets and hotel rooms on aggregator web sites. Many consumers are also price-sensitive regarding apparel, for which they frequently compare prices on e-commerce sites. By contrast, few consumers are generally price sensitive in beverage categories, either because prices are already relatively low or because they are willing to trade up for an interesting flavor or proposition, such as organic or healthy beverages.

The share of price-sensitive consumers within a specific category can also vary by location. Consumers in India are extremely sensitive about the price of restaurant or takeout meals, for example, while those in Japan, Mexico, Canada, and most of Europe are not. US consumers are more likely than Brazilians to choose the lowest-price skincare product; South Africans are the most likely to buy the lowest-priced snacks.

Value Consciousness Doesn’t Mean Price Sensitivity

Except in India, we found no direct correlation between consumers’ self-declared value consciousness and their actual behavior in terms of buying the lowest-priced products. Even though an ov

While 70% of German consumers said they are value conscious, for example, only 3.5% identified as price sensitive when they purchased their most recent beverage, snack, meal, or skincare product. Six percent of those German consumers indicated that they chose the lowest-priced automobile in their last purchase. And while almost 80% of US consumers identify themselves as value conscious, no more than 10% intentionally chose the lowest-price option in any of the ten categories we studied.

Why this contradiction? Consumers who state that they are value conscious can also be quality minded and brand conscious; they might also enjoy convenience or be interested in environmental sustainability. When consumers are simply stating how they feel, they are not required to choose among any of these considerations. But when making an actual purchase, they need to evaluate the options in front of them and make tradeoffs between price and other factors they value.

The Powerful Influence of Context

So when does price competitiveness make a difference? Demographics are less influential than one may assume, though we did find that age is a significant factor: 14% of Gen Z respondents (aged 18 to 25) are price sensitive compared with just 3% of those older than 56. But differences by gender and income level are much narrower, as are differences between consumers who dwell in cities and those in rural areas.

A significant difference maker is context, or the situation at the time of purchase. More consumers responded that they are likely to choose the lowest-price option when purchasing apparel for their children or spouse than for themselves, for example. And twice as many consumers are price sensitive when the item is a gift than when it is not. How the product will be used makes a difference as well: the average consumer in Australia cares least about price when she or he purchases apparel for casual, rather than professional, use. (See Exhibit 3.)

These responses show that price sensitivity is determined not just by who customers are, but also the context of their purchasing decisions. Marketers generally don’t spend enough time on understanding the latter—leaving value on the table in the process.

The Implications for Companies

Overall, our research confirms that while consumers say price is important, it’s usually not their overriding consideration when actually buying a product. And even when competitive pricing is a differentiator, consumer behavior depends on the market, the product category, and the context or situation.

With that in mind, it is critical for marketers to customize their pricing strategies and policies by country and purchasing circumstances; global uniform pricing policies are generally not optimal. Brands need a deeper understanding of when pricing really is likely to sway purchasing decisions—and how it works in combination with a wide range of factors. They also need a way to operationalize this knowledge without antagonizing consumers.

At an Asian coffee chain, for instance, we found that consumers were more price sensitive about their morning coffee than they were during their afternoon break. But simply charging different prices for a cup of coffee according to the time of day is neither a fair nor practical way to nuance pricing. The coffee shop should find other ways to tap into customers’ willingness to spend a bit more in the afternoon—for example, by offering coffee in combination with an ancillary product, such as a pastry. Similarly, in markets where consumers are more price sensitive when dining with children, restaurants might consider pricing entrees on kids’ menus that are lower than the competition while maintaining their conventional prices for adult meals.

As consumers continue to trade down in many product categories in the face of challenging economic times, pricing will figure prominently in the strategic discussions of marketers. As our research has shown, however, it is critical that brands gain a nuanced understanding of the motivations that drive price-sensitive purchases in specific markets, categories, and circumstances. Such knowledge can be the key to winning in a market—by being both price competitive and profitable.