With cargo revenues representing just 14% of airline totals as recently as 2019 and freight carriers often flying at half capacity, air freight has typically been the neglected stepchild of the airline industry . But when the COVID-19 crisis hit, air travel ground to a virtual halt and 2020 passenger revenues dropped by 69%. In contrast, cargo revenues surged 27% as a loss of space in the bellies of passenger jets triggered an unprecedented capacity shortage and threw off the traditional supply-demand balance. Suddenly, cargo was making record contributions to carriers’ bottom lines, throwing a lifeline to airlines hit hard by the pandemic: some trade lanes between individual regions saw air freight rates increase by 100% or more.

As air freight prices soared, so did spot-market bookings for cargo; in 2020, spot sales contributed up to 90% of bookings for individual airlines. Long-term contracts and bulk-allocation models diminished in importance, and the ability to price dynamically and strategically became critical for freight carriers looking to capture optimal revenues in a sellers’ market.

While passenger airlines have long had their own e-commerce channels and typically connect to online marketplaces such as Expedia and Trip.com, most air freight businesses do not yet have an e-sales outlet, nor do they have sophisticated internal pricing methodologies. Instead, freight booking remains a high-friction, one-to-one process, with carriers still relying on in-person negotiations and the use of emails and phone calls. The need for digital booking platforms and capabilities has therefore become urgent, touching a powerful spark to the long-smoldering requirement for digital innovation in the sector.

Many carriers have responded by beginning or accelerating migration to online sales, realizing that they cannot run their cargo operations effectively without digitizing them. This involves connecting their internal cargo management systems (CMS) to an e-sales channel, whether their own website or a digital distribution marketplace, such as cargo.one. While connecting to any online outlet is beneficial, a well-run marketplace will significantly increase revenue opportunities by giving carriers access to a wider group of potential customers, including small and midsize forwarders, than their own websites. Such a marketplace will also capture data not typically available through other channels—allowing airlines to evolve their marketing and pricing strategies and measure performance.

Additionally, as they make a move to e-sales, cargo carriers should look to improve their internal pricing systems to be more competitive and efficient. This will allow them to fill otherwise empty capacity when demand is low and achieve optimal returns when demand is high. Whether they do so immediately or over a period of months, our experience suggests they can boost net profits by as much as 12% in the first year.

Cargo: A New Airline Priority

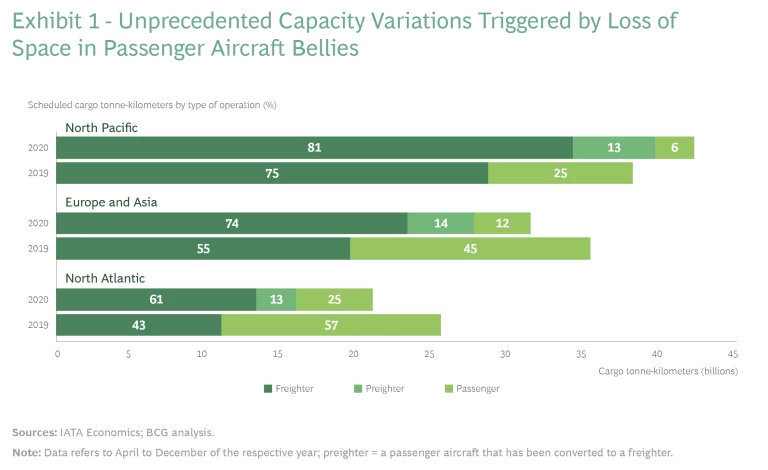

As passenger airlines furloughed workers, parked aircraft, and halted investment in non-core activities in March 2020, air freight became the unlikely center of industry attention. Since wide-body passenger flights typically reserve more than half of the available space in their lower holds (or “bellies”) for cargo, supply quickly became constrained. (See Exhibit 1.) Not coincidentally, search volume by freight forwarders on cargo.one, a digital distribution marketplace, saw a step-change increase of 42% in one week of early March 2020, and 2020 booking volume jumped to 700% of 2019 levels.

Airlines responded to the crunch with a 30% increase in freighter capacity between April 2020 and February 2021. Many passenger aircraft were even converted to freighters for the duration. Yet the shortage continues today—and has completely changed the air freight landscape.

Falling capacity, exacerbated by expanding e-commerce volumes in the lockdown, quickly led to a surge in air freight prices. Under these market conditions, the industry was able to increase average freight revenues per tonne-kilometer by 40% in 2020, while freight load factors saw all-time highs, rising 27% to 28% above prepandemic levels. Air cargo industry revenues, in turn, rose from $100 billion in 2019 to $128 billion in 2020, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

While the increase in cargo revenues did not fully offset losses on the passenger side, many airlines have been supported by their cargo operations over recent months. China Airlines was able to remain profitable in 2020 because it was sustained by over 1,000 monthly freighter flights on otherwise empty passenger aircraft—and a corresponding 87% increase in cargo revenue. Cargo-only carriers, such as Cargolux, Atlas Air, and AirBridgeCargo, celebrated record profits in 2020.

The Ascendance of the Spot Market

As prices climbed and freight forwarders searched for scarce capacity, more and more bookings were pushed into the spot market. Long-term contracts negotiated one-on-one with freight forwarders—which traditionally made up 90% of bookings at agreed bulk rates—quickly began to take a back seat.

In the day-to-day operations of freight carriers, this meant that traditional ways of doing business—through relatively infrequent emails and phone calls—became inadequate, with staff overstretched by the unprecedented flood of requests. More critically, freight carriers were leaving money on the table, missing opportunities to price each booking dynamically and in accordance with the strategy devised for each market.

Time to Catch Up to Passenger Airlines

Passenger airlines have long been able to quote prices dynamically for specific “buckets” of seats based on dimensions such as market type, cabin, season, and days to departure. And within the complexity of the pandemic environment, many are now revisiting their revenue management functions , including the use of machine learning (ML) to forecast demand and elasticity and the introduction of methods for pricing individual seats continuously along a curve. Most have their own high-functioning websites as well as connections to several online marketplaces such as Expedia and Trip.com.

In contrast, sales-system capabilities in air freight businesses have lagged those of their passenger counterparts, whether in supporting consistent quotation practices for the same or a similar request or in offering dynamic pricing. Digital booking was nearly nonexistent prior to 2018, and although airlines began to focus on the opportunities for digital innovation in sales and booking several years ago, progress has been relatively slow and instant-confirmation booking is still quite new for most carriers and forwarders.

As a result, carriers often have trouble adjusting prices in response to short-term changes in supply or demand. Many emails can be required to create a single booking, pricing for individual customers is difficult to execute, and response times are notoriously slow.

A Powerful New Booking Channel

Client expectations have risen, and the selling paradigm has clearly begun to move toward e-sales—in particular, digital distribution platforms.

These internal issues, along with the pressures resulting from the pandemic, have sped the adoption of digital booking in recent months and led multiple carriers to adopt digital distribution—whether via B2B marketplaces alone or through a combination of online marketplaces and their own channels.

Simultaneously, as we’ve seen in the retail sector, client expectations have risen along with the propensity to use e-sales—in particular, digital distribution platforms, which streamline many elements of the booking and shipping process . (See the sidebar.) As a result, the selling paradigm has clearly begun to move away from offline, two-party negotiations and toward an active digital marketplace.

The Virtues of Digital Distribution Marketplaces

Carriers can rely on a well-run digital marketplace to manage the necessary pricing algorithms, formulating rates instantly in response to requests from potential customers on the platform. This can significantly reduce the cost of establishing equally successful digital sales volumes independently—and takes far less time. It also requires less digital infrastructure (such as a website, pricing mechanism, cloud server, and customer-acquisition and -support software) to reach customers and significantly lowers upfront expenditures.

Alternatively, online marketplaces also offer carriers a platform for the incremental development of these sales-related business processes internally. This means that carriers can test and roll out new revenue-management approaches, data analytics, and pricing logic on their own channel, with the goal of eventually generating dynamic prices and even potentially leapfrogging the standard of air passenger ticket-sales technology. Such offerings support other offline sales channels as well, as lessons about product positioning, underserved pockets of demand, and pricing are typically transferable.

For those carriers concerned about moving away from a heretofore successful relationship-based business model, we note that automated booking allows teams to use time previously spent on email booking to focus on what matters: providing good customer service, quality, and value.

Along the way, online marketplaces also allow carriers to address a fragmented customer base of smaller and midsize forwarders, reflecting a broader cross-section of demand. For example, 76% of bookings on the cargo.one platform come from forwarders outside of the global top 50.

In turn, these platforms offer freight forwarders a highly user-friendly solution, primarily due to data that has been cleaned and prepared. Good data allows forwarders searching for individual bookings to get details not only on price and quantity, but on considerations such as temperature control, departure and destination, and adequate capacity for the requested shipment before gathering quotes from the site’s carrier partners—a customer-centric approach that boosts adoption and engagement. In addition, digital platforms offer instant booking confirmations and can enable intermodality, allowing forwarders to book a plane and a truck as one trip rather than individual steps.

Note that only if the distribution partner has the capacity and execution power to grow the partnership across geographies, commodities, and customer touchpoints—including tracking, post-booking service, and billing—can carriers make the most of optimizing their internal digitization.

Europe has been an early testing ground and has already seen a growing adoption rate for digital cargo booking among both forwarders and airlines. Air France-KLM’s myCargo platform, which launched in 2018, has arguably led this change and has been a significant catalyst for digital adoption by other carriers, including IAG Cargo, Finnair Cargo, and TAP Air Portugal. European forwarders have since rapidly adopted digital processes, allowing airlines to achieve digital booking shares as high as 30%, according to our analysis.

The Need for Meaningful Business Change

As freight carriers move to online sales, they should follow another example from passenger airlines as well—introducing sophisticated revenue-management systems to price their offerings dynamically and strategically. They should, for example, use these systems to price shipments by the cargo’s origin and destination rather than as the sum of the prices of connecting legs of the trip, as many do. And they should use them to partner with other shipping providers—not just other airlines through interline pricing, but also trucking companies. This combination of dynamic pricing and improved distribution capabilities can boost revenues per kilometer, load factors, and profitability. Note that dynamic pricing is not a choice between technology and people. Rather, it combines the strengths of both forms of intelligence . And it should not be thought of as a solution that is purchased off the shelf and implemented overnight, but instead as a journey unique to each organization.

In the passenger airline business, such revenue management models were developed 20 to 30 years ago, using data analytics to maximize flight revenues by selling each seat at the optimal time and the optimal price. These structures look at past data and make assumptions about where to steer prices, changing them dynamically as capacity and demand shift—rather than, say, offering a single price for each seat that varies only with days to departure. As the systems have evolved, dynamic bundling, offer and order management, flexible retailing, and continuous pricing have replaced legacy revenue management objectives. In addition, IATA developed its New Distribution Capability (NDC) program, which supports these offerings on all distribution channels.

Dynamic bundling, offer and order management, flexible retailing, and continuous pricing have replaced legacy revenue management objectives.

However, dynamic pricing has made much smaller inroads into air cargo to date due to challenges typical of the cargo business model and legacy industry practices, which have delayed its adoption and implementation. Air freight carriers need to keep these issues in mind as they build their own model.

Pricing Challenges. Typical air freight challenges include the following pricing issues:

- Imbalances. The structure of cargo demand typically means that some freight lanes are much more heavily used than others, and some directions are stronger than others.

- Short Booking Windows. Most bookings today are made fewer than 14 days before the flight, vis-à-vis passenger bookings, which can start as early as 300 days prior.

- Many Dimensions. Freight carriers must optimize many elements of each booking, accounting for volume, weight, density, temperature control (e.g., for pharmaceuticals), security, oversize freight, and more complicated connections. Carriers must also consider that e-commerce is bringing more complexity to revenue optimization due to freight category diversity and lower shipment density.

- Intermodal Shipments. To achieve more comprehensive and efficient distribution, carriers often use airports as logistical centers where shipments are concentrated and from which they are then dispatched by truck to their ultimate destination. This system entails a complex pricing design.

Demand and Supply Forecasting. Another typical challenge revolves around forecasts for air freight demand, which are frequently unreliable. The issue typically stems from factors such as poor booking-data quality, with some bookings processed outside of the CMS, and poor freighter-schedule reliability.

In addition, accurately forecasting available capacity for belly-only freight carriers, such as Delta and American, is complex. Reasons include often-inaccurate passenger bookings, operating conditions that limit an aircraft’s cargo payload, and the fact that airlines frequently upsize or downsize the plane close to departure for passenger-margin optimization. Having less capacity to sell, bellies are also more vulnerable to the potential inaccuracies of booked volume or weight compared with the actual volume or weight measured at departure, requiring far more accurate analytics as well as tougher industry discipline to use the space optimally.

Capacity Management and Cargo Mix. The implementation of dynamic pricing has also been hampered by legacy practices in air cargo, including:

- Bulk Contracts and Large Customers. Commercial freighter operations typically have a great deal of capacity to fill and use a higher share of bulk contracts and charters to reduce risk, making them less amenable to dynamic pricing. In addition, the freight forwarding business is relatively concentrated, with the 20 top companies generating about 50% of total air cargo revenues, according to Global Supply Chain Intelligence. Big forwarders have therefore typically been able to command very low rates, and dynamic pricing algorithms offer much less bargaining power.

- Capacity for Spot Requests Not Planned Methodically. Residual freighter space dedicated to free flow and last-minute sales at spot prices is often planned unmethodically. In addition, a lack of opportunistic operating models that allow freight carriers to take any last-minute bookings or shift shipping from flight to flight, for example, have often been a barrier to the application of pricing and freight-mix optimization.

Lack of opportunistic operating models have often been a barrier to the application of pricing and freight-mix optimization.

Process, Organization, Technology. Other legacy practices hampering the implementation of dynamic pricing in cargo include:

- Poor Discipline. Most airlines inconsistently set, and even less frequently enforce, rules around their cargo bookings—from booking windows to cancellation terms. The costs of low materialization rates from less reliable forwarders are often borne by the carriers if capacity remains empty or extra work is needed, and they are rarely reflected in price differentials.

- Regional Sales. Pricing for commercial freighters is usually managed by a regional sales office rather than a central pricing team due to the desire for proximity to freight forwarders’ markets and to the priority placed on contract management to date. This implies the use of non-standard methodologies, systems, and data across regions.

- Technology Barriers. Several technological barriers, including limited systems capabilities, affect both carriers and bellies. Many outdated CMSs, for example, have few interfacing capabilities, and there is often a lack of standard communication protocols between parties. In addition, a lack of adequate pricing data often limits systems’ ability to price cargo at a granular level, such as for specific flights or dates. Partially manual booking or ticketing processes also lead to poor data quality; for example, incomplete booking information.

A Roadmap to Dynamic Pricing

The current complex demand and supply conditions for cargo carriers reinforce the need for dynamic pricing practices, which can be much more effective than manual or partially automated pricing methods. And thanks to greater volumes of data and smarter analytics, coupled with new distribution platform capabilities, many of the traditional challenges and practices no longer pose a serious obstacle to adoption of these practices. Carriers should therefore invest pragmatically in digital use cases that support the evolution of dynamic pricing, gradually adopting new processes and ways of working while reaping intermediate returns on their investments.

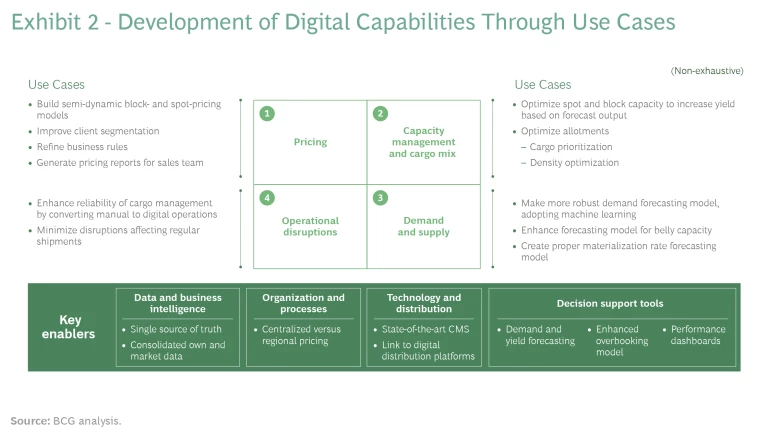

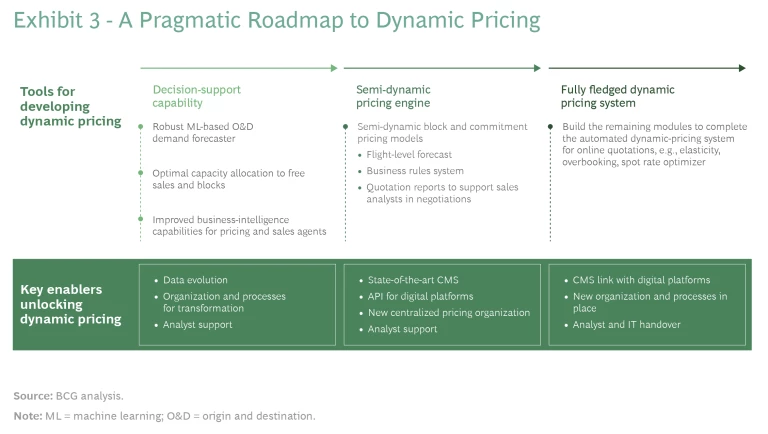

Roll out digital innovation step by step. We propose that the ideal roadmap to building new digital capabilities is step by step—a gradual development of the appropriate capabilities, rather than the purchase of an off-the-shelf solution. This pragmatic approach will allow air freight carriers to customize their technologies and transform their existing organizational capabilities and cross-functional processes, thus reducing the risk of failure from attempting a complex, externally sourced systems implementation. (See Exhibit 2.)

One important step in this process will be the creation of decision-support capabilities that, with models such as an ML-based demand and capacity forecaster and a yield-displacement model, will be able to provide an optimal split of capacity between spot and block commitments.

Another key step in the evolution of digital capabilities will be the development of a semi-dynamic block-commitment pricing model. Typically, this is a business-rule-based model that accounts for client segmentation and cargo categories and generates quotations to support sales analysts in negotiations based on historical and actual demand and flight performance. We call this a contract-quote generator.

The last step is to create a fully dynamic spot-pricing model that combines forecasts, elasticity, and other data to continually optimize the price of each cargo category and fulfil online quotations when the CMS and distribution platforms are linked. (See Exhibit 3.)

Personalize the process. Digital marketplaces for air cargo distribution are B2B channels. Every customer is associated with a contract and identified at the beginning of the shopping session. Dynamic pricing algorithms calculate the hurdle rate for future flights, dates, and categories; then other business logic is applied, including existing contractual agreed rates, the estimated customer wallet (or purchasing ability), customer behaviors such as destination preferences, and elements of the customer’s lifetime value.

As carriers create their own process, they should also model this “personalized” logic component—which accounts for customer performance and behaviors such as freight booked versus shipped—using machine learning to estimate the likelihood of a purchase at different price points and at the given time to departure. Carriers should also generate a price sensitivity curve for every relevant customer or cluster of customers and calculate a target price.

Enhance the core. Along the way, we recommend that carriers enhance several dimensions of their core operations, including the following:

- Improve data quality. Improved processes will naturally result in more reliable data. Carriers should use data integration models to ensure that all internal data is combined—offering a single source of truth—and able to interface with any additional repositories, such as industry market data. A good data integration model will also offer a richer set of data, and the richer the data, the better the machine learning model.

- Improve booking processes. Carriers should ensure that booking tasks can run on the same digital platform, typically the CMS—allowing them to drop any external repositories and manual operations.

- Invest in the right human capabilities. Carriers should start training and hiring early in the transformation process, as this is an essential step to creating a foundation for systemic adoption. One part of the process will be creating new roles in the organization to maintain and improve the new operating models—such as data scientists to calibrate the ML model.

- Adopt state-of-the-art CMS. Carriers need to offer an efficient digital workflow to their customer and operations teams, from pricing and inventory to booking, security, and other functions. This CMS workflow should be open to online marketplaces and other systems within the cargo distribution chain, including e-commerce players and forwarders.

- Drive organizational change. Building a new system, improving data, and generating sophisticated analytics will all be useless without fundamental change. Some carriers will need to reorganize their processes and even their structure. For example, carriers should ensure that their pricing responsibility is centralized, eventually establishing a central sales and pricing unit. They should also separate the pricing and sales organizations to maintain an organic tension between revenues and margins.

During their digital evolutions, carriers should take care to learn from the experiences of passenger airlines, including avoiding revenue-optimization solutions that are too complex or too early in the progression of the internal team’s capabilities; maintaining control of core components, such as distribution modules and pricing IP, rather than outsourcing them to less expensive third-party providers; prioritizing the optimization of returns as the organization evolves; and remembering that there are early benefits to be gained by enhancing internal processes even before the data and technical backbone are finalized. Learning from the past will be essential to ensuring sophisticated, dynamic freight pricing for the future.