A DTC channel that adds to total growth allows a company to collect valuable consumer data, personalize the experience, quickly launch and test new products, and grow the business.

The attitude toward direct-to-consumer (DTC) initiatives has changed almost overnight. Large consumer brands used to worry that such initiatives would create channel conflict and cannibalize the business—not to mention displease retail partners . Now they realize that the DTC approach allows them to collect valuable consumer data, personalize the experience, quickly launch and test new products, and grow the business. What’s more, as the pandemic has revealed, it aligns with the way many consumers want to interact with brands.

Today, companies don’t have to choose between DTC channels and retail partners. Instead, they just have to ensure that the DTC channel they establish adds to total growth. Consumer brands that are not already investing time to evaluate and improve their DTC capabilities need to start doing so immediately—or face losing market share to more nimble rivals. To help, we have codified a set of learnings for consumer brands to rapidly accelerate their DTC efforts and reap the benefits.

DTC Is Here to Stay

Our definition of DTC brands is expansive. It includes:

- Digitally native, online-first consumer brands with a portfolio focused on a particular product category

- Retail brands with stores that fully embrace digital channels through their own websites (see “The Retail Response”)

- Well-established consumer brands that are sold mainly by retail partners and are experimenting with DTC as a new business model

The Retail Response

As brands design their direct-to-consumer approaches, their retail partners will need to think creatively about how to stay relevant. Some points to consider:

- Protect first-party customer data and put more focus on acquiring, protecting, and utilizing it to personalize consumer engagement.

- Build out their own online, omnichannel offering to acquire, win, and own access to new groups of consumers.

- Focus on such metrics as lifetime value and customer acquisition costs in addition to straight revenue growth.

- Continue to build out and control a portfolio of private brands, which will not only drive improved margins but also differentiate the company from other online players.

- Build and manage a portfolio of new business models, investing in those that work and divesting where needed.

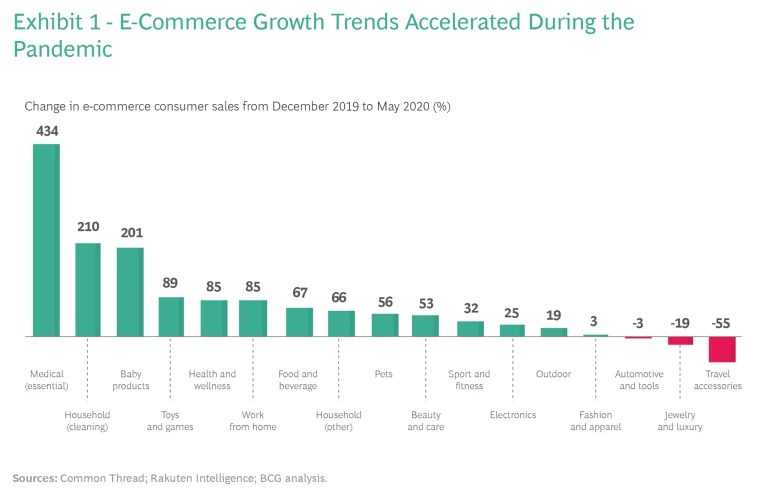

Given the rate of e-commerce growth , these companies must either quickly establish DTC capabilities or continue to build their existing functions. From December 2019 to May 2020, US e-commerce sales in the food and beverage category—long considered a laggard in the online space—grew by 67% year over year. (See Exhibit 1.) The growth in just those few months equals the growth in the previous ten years combined. Large consumer brands that are just starting to address the DTC question need to fundamentally rethink their product-market fit and go-to-market strategies . The pandemic will recede, but e-commerce and the need for a DTC strategy will not.

Historically, large companies have designed their product-market fit and go-to-market strategies with the express purpose of increasing how fast products fly off the store shelf. They used broad marketing campaigns to build product awareness, created attractive packaging to stand out, and paid diligent attention to keeping prices low. But in a DTC world, many of these priorities are de-emphasized.

Instead of maintaining low prices for products on shelves, brands must learn to navigate the complexities of channel conflict and new revenue models, such as subscriptions.

Instead of broad marketing campaigns, the DTC model uses one-to-one, precision marketing capabilities and substantial digital assets, such as images, videos, and reviews. Instead of attractive packaging to entice buyers, the DTC approach requires simple packaging designed for delivery. And instead of maintaining low prices for products on shelves, brands must learn to navigate the complexities of channel conflict and new revenue models, such as subscriptions. Fulfillments costs are also an issue. Instead of making deliveries by the truckload to retailers, companies must develop (or partner to use) a supply chain that efficiently delivers individual boxes to private homes.

For example, Peloton, a leading interactive fitness platform, has embedded software and connectivity into traditional hardware products—stationary bikes and treadmills—to give customers direct access to a services ecosystem and create stickiness to the platform. About 20% of revenue comes from subscriptions, and the company has a 93% customer retention rate. Analysts attribute up to 85% of the company’s valuation to subscriptions rather than to sales of the products themselves.

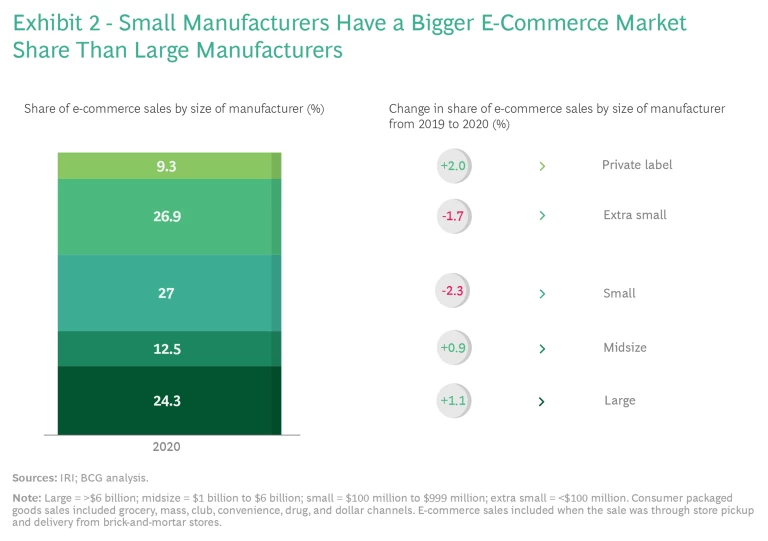

Scale Advantages Diminish

On top of these trends, large brands are continuing to lose their traditional scale advantages as barriers to entry fall. Small, attacker brands are adept at exploiting shifts in the industry, leveraging data, and moving quickly to hunt out niche pockets of demand to gain outsize market share. From 2016 to 2020, private-label brands, extra-small manufacturers (with less than $100 million in sales), and small manufacturers ($100 million to $999 million in sales) gained market share at the expense of large manufacturers (more than $6 billion in sales). In today’s markets, attacker brands can:

- Rent capacity from large manufacturers—some designed specifically to support startups—to achieve scale and stay asset light

- Use fast-growing, capital-light retail formats, such as pop-ups, to quickly create an offline presence for a digital brand

- Build brands and target niche markets without big upfront costs, using digital media and personalized marketing

- Leverage peer recommendations and networks, which consumers increasingly trust more than expensive marketing campaigns

- Contract with low-cost e-commerce fulfillment centers

Of course, attacker brands don’t have a monopoly on exploiting these shifts. Ben & Jerry’s, a wholly owned subsidiary of Unilever, has long used social media to voice social-mission activities and highlight its values and activist product development initiatives. The company now uses social media specifically to promote DTC initiatives.

Most companies, however, are behind in these areas. And considering the surging growth in e-commerce, it’s an ominous sign for large consumer brands that their share of total e-commerce sales in the US trails that of both small and extra-small manufacturers. (See Exhibit 2.)

Using the DTC Approach to Play Offense

Adopting a DTC strategy is not all about playing defense against attacker brands. Companies can use the approach to take the offensive, forging deep customer relationships that improve their competitive positioning among both peers and upstarts. We’ve identified several major DTC objectives:

- Collect and own data directly from customers to create feedback loops. This helps companies to not only optimize the customer journey but also allocate resources correctly in order to drive innovation and production. Indeed, we have worked with several companies where the DTC channel has become a primary source of consumer insights.

- Personalize omnichannel experiences to drive incremental revenues from customers and exercise more control over the user experience.

- Use personalized marketing to reduce customer acquisition costs, improve retention, and maximize customer lifetime value.

- Manage a portfolio of DTC offerings and reinvent the demand model by shifting from category management to portfolio management. Using data gathered from consumers, create new products to fulfill niches in demand and differentiate the DTC channel from mass retail.

- Launch and test new innovative products on a smaller scale with a faster time to market, and then adjust on the basis of consumer feedback.

- Move beyond just selling products and incorporate services into a broader, more holistic offering to customers.

- Own the storefront to combat pricing pressures because, in the DTC model, there are no adjacent shelves with private labels that drive down prices. A consumer brand can set package sizes, product offerings, and pricing as it sees fit to serve the customer.

- Free up working capital and reduce waste by shifting the supply chain from “design-make-sell” to “sell-design-make.” When companies communicate with customers directly to understand what they want before making the product, they can carry much less inventory and produce only what customers will actually purchase.

Of course, not all well-established brands need convincing that the DTC model offers an important avenue of growth. Many apparel and athletics companies embraced the DTC approach well ahead of other consumer packaged goods companies . Nike, for example, has been prioritizing DTC investment for years. Today, approximately 39% of sales are DTC, and the company aims to reach 50% by 2023. It has also acquired three data analytics companies: Celect (predictive analytics), Zodiac (demand sensing), and Datalogue (machine learning). With demand sensing, Nike can redistribute products, personalize recommendations, and use push marketing to manage lifetime value. And with sentiment analysis, it can create new products and services, such as Nike Training Club.

What It Takes to Succeed

As is often the case when launching new initiatives, companies can either buy or build the capabilities they need. When acquiring an existing DTC brand, the idea is usually to leverage that brand’s capabilities across the enterprise. This approach offers speed to market but can come with a heavy price tag, sometimes 10 to 20 times the cost of building in-house. Moreover, a large company might have difficulty integrating the DTC brand with its existing business if company cultures clash, and that could put growth synergies at risk.

Alternatively, a company could set out to build DTC capabilities internally. Though the upfront investment is much lower in this scenario, DTC leaders must be empowered to act quickly if they are to succeed. Decisions and investments need to be made in a matter of weeks—not months or years. When DTC leaders are given this authority, they can build a DTC capability organically and establish digital infrastructure that supports both the core business and the new channel. (See Exhibit 3.)

The need to act now has never been more pressing. We see five broad areas that companies should address when designing their DTC approach.

Vision and Strategy. A company needs to articulate its ambition for how it will use the DTC channel for product innovation and to enhance customer shopping missions, how these efforts will complement existing channels and retail operations, and how the company will integrate the DTC channel into marketing, operations, and sales. To avoid wasteful competition between the retail and DTC teams for the same consumers, companies should carefully set expectations, manage KPIs for the DTC and retail channels, allocate resources, and align on the economics of the DTC business.

Creating and preserving this internal alignment requires a deep understanding of the customer. Which shopping missions do they conduct online, and which do they conduct offline? The company can use the answers to those questions to develop DTC initiatives that address specific customer journeys and solve pain points, such as hard-to-find items, to improve the experience. Demonstrating this kind of strong customer value is critical to ensure that pricing and margins are sufficient to fund the DTC channel’s operating costs, which are typically higher than those for retail channels—at least initially.

In many sectors, companies are starting to use DTC channels to deliver a more integrated customer experience, including educating consumers about new offerings and opportunities. Kohler, for example, has built a differentiated experience that takes the customer from inspiration through installation. According to the company’s website, this includes a virtual design service, an online product and design discovery quiz that mixes functional and aspirational questions, and a free 30-minute virtual product consultation.

Product and Service Offering. A company needs to decide which products and services it’s going to sell through the online channel and how it will position them to avoid conflicting with store operations. This might involve dedicating some brands to online only, changing package sizes for the online channel, or making the DTC channel a more personalized version of the offline version (think of, for example, personalized M&Ms and Oreos). That said, product alignment doesn’t have to be perfect from the start. It’s better to experiment, quickly learn, and then refine the product or service offering rather than to delay the launch of a DTC channel in an effort to perfect the mix.

It’s better to experiment, quickly learn, and then refine the product or service offering rather than to delay the launch of a DTC channel in an effort to perfect the mix.

Companies should think about their products in terms of the actual physical items and the digital assets that display those items to the world. That means building content that enhances both the online retail experience and the DTC experience using formats such as images, text descriptions, reviews, videos, and social media influencers.

Operating Model. The operating model should apportion decision rights and budgets across the DTC channel and the store business so that the two generate additional revenue and the teams are not in conflict. One way to avoid conflict is to use performance marketing as a kind of control tower that directs traffic to the ideal landing spot—DTC versus retail versus other channels. For example, in the home goods and consumer durables categories, professional remodelers are often better served through non-DTC channels, and a company should not waste DTC dollars trying to convert them.

As part of the DTC operating model design, a company needs to decide which tasks it’s going to perform in-house and which it will outsource, as well as whether it will leverage third parties to remain asset light—to do pop-ups, for example, or distribution or manufacturing.

Shifting the supply chain from design-make-sell to sell-design-make is a compelling business case for the DTC approach because it frees up working capital and reduces waste.

Technology Acquisition. Putting the right technology stack in place is a business project, not an IT project, which means that the business case for the technology needs to be clear before spending many millions of dollars. So instead of using a five-year, waterfall approach to try to build the perfect end-state website for the DTC business, the company should get a pilot into market quickly and start learning. This approach will facilitate lighthouse wins across the company, driving focus and enthusiasm for the DTC approach.

Only when the pilots have demonstrated a great business case and solid ROI should the company commit to the full tech stack build. We’ve heard of some IT teams pushing back on this agile approach, arguing for a complete end-to-end design that would take months (if not years) to accomplish. But leadership should be willing to challenge these IT teams: if a small startup can be online and selling products in less than a month, evolving the technology and operations along the way, why should a larger company spend months detailing process and technology flows to achieve the same end? In our experience, these IT teams are thinking about DTC channel development in the wrong way, missing an opportunity to move fast and repair problems on the fly.

Team Development. DTC teams need to be cross-functional and comprise a wider variety of skills than those found within most traditional brand teams. They need to be more analytical, data oriented, performance driven, and agile. To get up and running quickly, organizations should initially seek to establish a minimum viable DTC organization: a small team with just the most critical capabilities needed to create differentiation and demonstrate the value of the channel. The exact combination of critical capabilities will vary by industry and geography.

Until recently, many large brands didn’t consider pursuing a DTC model to be worth the effort. But the rapid growth of e-commerce spurred by the pandemic has changed the calculus entirely. Now the question is not whether to put a DTC strategy in place at all, but how quickly to do so and whether to build the team internally or acquire a DTC brand to jump-start the effort. Companies can look to successful brands that have already waded into the DTC waters for best practices about how to start conducting business in new ways that their customers have quickly come to expect and prefer.