New health therapies that enhance the quality of life are tremendously important to patients. But when these therapies cost more than existing ones, payers are reluctant to cover them without evidence that they will also lower the overall cost of care. For patients as well as for the pharmaceutical and medtech companies that are developing these therapies, determining how to convince payers to expand access to these treatments is a pressing concern.

With this in mind, BCG conducted a survey and in-depth interviews to understand how US payers evaluate quality-of-life therapies to make coverage decisions. We found that the willingness to cover these therapies varies by payer type and condition, but payers can be convinced with the right real-world evidence. In this article, we distill our findings and present a five-step approach that pharma and medtech companies can use to demonstrate therapeutic value.

Payers’ Views of Quality-of-Life Benefits

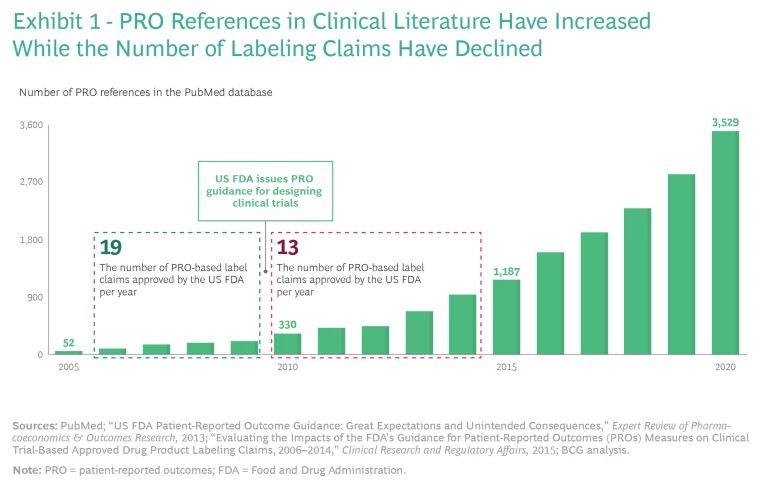

Researchers have used patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to assess improvements in patients’ quality of life for decades. Over time, PROs increasingly became important for R&D, clinical trials, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals. In cases where PROs were clinically validated—sometimes across hundreds of thousands of patients—the data was quite robust. Consequently, references to PRO data in clinical literature exploded from 2005 through 2020.

So why didn’t this attention to PROs translate into payer coverage of quality-of-life therapies on a significant scale? PRO claims carry more weight with payers when they appear on an FDA label, but in 2010, the FDA published guidance for designing clinical trials that led to fewer PRO-based label claims receiving FDA approval, even as the number of references to PRO data in clinical literature increased. (See Exhibit 1.) As a result, few FDA labels currently carry PRO claims unless they treat a condition that is difficult or impossible to evaluate without PRO data. Examples of such drugs and the conditions they treat include Linzess (irritable bowel syndrome), Jakafi (myelofibrosis), Nucala (asthma), and Nucynta (severe acute pain).

A few therapies have benefited from including PRO data even if it pertains to how the drug improves the symptoms or consequences of the condition, rather than the condition. For example, Tremfya, a drug for psoriatic arthritis, uses PRO data to demonstrate that it increases patients’ ability to perform daily activities, such as dressing, washing, eating, and walking. Having this PRO data on its FDA label has helped Tremfya stand out from the crowded market for autoimmune disease therapies.

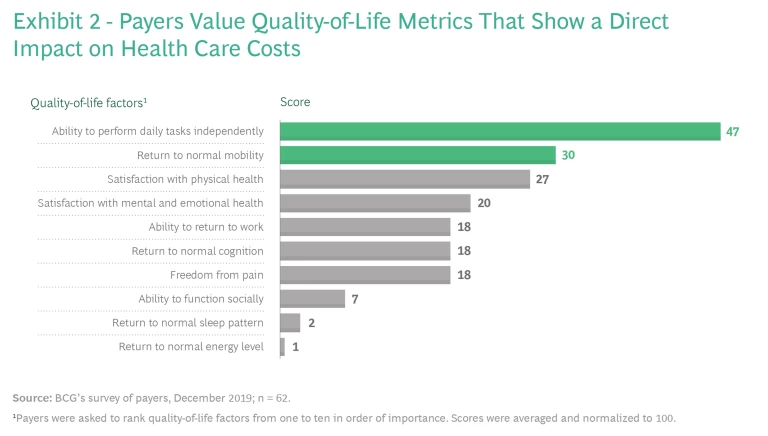

Even so, providing quality-of-life benefits doesn’t always translate into coverage and improved patient access because payers usually care most about clinical efficacy and cost. Payers typically evaluate efficacy using what they consider to be objective measures of endpoints specific to the disease, such as living longer and physiological improvements assessed through diagnostic tests. And because payers are focused on costs, to gain coverage, therapies that enhance patients’ quality of life need to demonstrate improvements in the total cost of care, such as by reducing the number of hospital readmissions or by increasing patients’ ability to perform tasks independently and avoid nursing care. (See Exhibit 2.)

Since PROs are not generally viewed as objective, many payers do not weigh them heavily in coverage decisions. Indeed, patients and pharma and medtech companies face a high level of skepticism about the value of PROs. “Patient-reported outcomes are very subjective, not very scientific, and rely on patients to tell you how they feel,” said a former vice president of pharmacy at a payer. “Frankly, how patients feel doesn’t translate into money for payers.” That might be an unusually blunt statement, but it’s not a unique sentiment.

The Differences Among Payers

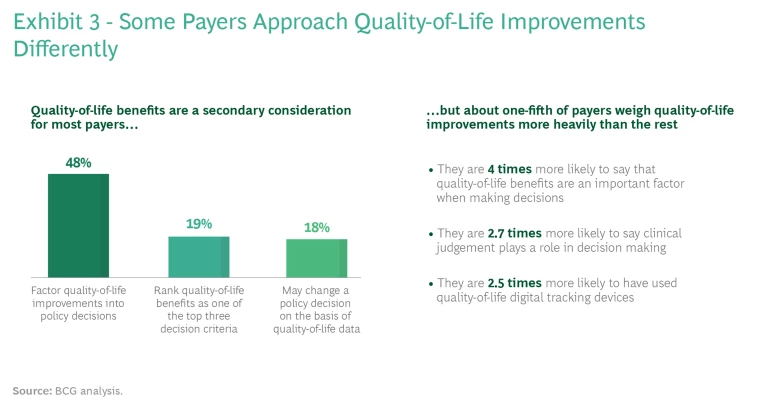

It’s important for pharma and medtech companies to understand that not all payers approach quality-of-life issues in the same way. (See Exhibit 3.) For example, on the basis of our interviews, payers that focus on employer-sponsored health insurance tend to weigh quality-of-life outcomes more heavily than other commercial payers; that’s because employers usually take employees’ complaints about coverage quite seriously. Other commercial payers will sometimes provide coverage for therapies that enhance patients’ quality of life, but they are more likely to enforce utilization controls, such as higher co-pays, on patients.

Meanwhile, payers whose coverage is funded mainly by the government (such as Medicare and Medicaid) are very focused on cost-effectiveness. This is out of necessity. The government holds payers to traditional metrics that can make covering quality-of-life therapies difficult. Therefore, these payers often do not cover a therapy that costs more than the prior standard of care, despite the quality-of-life benefits.

Payers value PROs more highly when drug makers rely heavily on PROs to measure a therapy’s efficacy.

How much payers weigh PROs and patients’ quality of life also varies somewhat by the condition. For example, payers value PROs more highly when drug makers rely heavily on PROs to measure a therapy’s efficacy. Such therapies include treatments for depression and migraines. Commercial payers—some of which did not cover mental health for all patients until the Affordable Care Act went into effect—consider most evidence in the mental health area very subjective, with PROs the least bad data. “Subjective data gets looked at more heavily when objective data is not possible,” said a former deputy chief medical officer at a top-five payer. Payers implement controls, however. Step edits, which require that patients try inexpensive generic therapies first, are widely used.

Government payers, by comparison, have been covering mental health for longer. For example, Medicare ensures mental health coverage by identifying antidepressants and antipsychotic drugs as protected classes of drugs. The government recognizes that it will ultimately bear a greater total cost for patients with untreated mental health issues through disability coverage and other social-support benefits.

Besides these variations by payer types and therapeutic areas, there are also variations among individual decision makers. Some thought leaders in payer organizations are already combining their own clinical judgment with digital tools to weigh quality-of-life benefits more heavily in their coverage decisions. This suggests that appealing to a decision maker’s clinical experience could help convert some skeptics.

A Five-Step Approach

Given this backdrop, pharma and medtech companies need to think carefully about how to ensure that patients have access to the therapies they develop. That means translating PROs into metrics that demonstrate a therapy’s value so payers understand why covering it makes financial sense. Fortuitously, recent advances in remote digital monitoring as well as data and analytics allow pharma and medtech companies to measure and value their therapy’s impact on patients’ quality of life more precisely than ever. Innovators developing therapies that improve the quality of life should take the following five-step approach to demonstrating value to payers and increasing patient access.

Target specific stakeholders. The first step is to identify the decision makers who are most likely to appreciate quality-of-life benefits—and then make sure the data reaches them. These stakeholders typically include medical directors, physician associations that create treatment guidelines, and payer and hospital advisors who write treatment pathway protocols for their health care provider networks to follow.

Assess quality-of-life improvements. Early in the R&D process, evaluate how new treatments affect patients’ quality of life and that of their caregivers. When possible, use digital tracking and analytics or longitudinal trend analysis, or both, to gather detailed evidence and improve the perceived objectivity of the results. Identify and describe the specific steps that patients and caregivers should take when using the new therapy to maximize quality-of-life outcomes.

Gather quality-of-life outcomes. When conducting clinical trials, use well-established survey tools that are designed to collect PROs and measure quality-of-life outcomes. Such tools will increase the probability that payers will recognize the results. Be sure to comply with the FDA’s PRO guidance when designing clinical trials so that PRO-based claims have a greater chance of inclusion on the FDA-approved label. Include specific PROs as primary endpoints for clinical trials to increase payer acceptance.

Translate outcomes into metrics to demonstrate value. To build broad support for a new therapy, translate quality-of-life outcomes into metrics that matter to various stakeholders—payers, providers, and patients.

To build credibility with payers, show how improving a patient’s quality of life reduces the cost of care.

To build credibility with payers, in particular, show how improving a patient’s quality of life reduces the total cost of care, and then validate the evidence with industry players. For example, run pilot programs with payers to demonstrate that quality-of-life improvements are associated with higher employee productivity and lower absenteeism—results that employers care about deeply. “You need to show that [improving] quality of life translates into a dollar savings or better efficacy or safety outcomes,” said a pharmacy director at a top-five payer.

Additionally, it is critical to work with clinical organizations to ensure that findings are incorporated into updated care guidelines. Payers cited peer-reviewed clinical data (74%) and treatment guidelines (87%) as far and away the most important sources of information when evaluating the clinical value of new therapies.

Build a quality-of-life plan into the long-term strategy. Quality-of-life improvements will become more important to payers as value-based health care gains traction over the next decade. Value-based health care rewards providers for helping make patients’ lives healthier. It is a marked shift from the fee for service (FFS) model, in which payers reimburse providers for each health care service they render, rewarding them for quantity rather than quality. With this trend in mind, innovators will want to use quality-of-life results to inform their own long-term R&D and reimbursement strategies.

Although the shift from FFS to value-based payments is happening more slowly than many people originally expected, momentum is building. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is easing best-price regulations to incentivize value-based arrangements; many state governments are pushing for reimbursement models with a value-based component; some big commercial players are investing in value-based capabilities at scale, such as buying physician groups; and payers are increasingly distributing bonuses on the basis of quality scores (for which patient satisfaction is a major contributing factor). “Value-based arrangements will become a major way for innovators to leverage these quality-of-life outcomes,” said the former deputy chief medical officer at a top-five payer.

Gaining Greater Traction

While there’s been progress across the health care value chain in considering quality-of-life issues, quality-of-life outcomes are still valued less than other health care results that are perceived as more objective. Innovators can accelerate progress and expand access to treatments by quantifying improvements—using PROs, digital tracking, and data analysis—and demonstrating value to payers, providers, and patients.

Longer term, pharma and medtech companies that focus on improving patients’ quality of life, in addition to measuring outcomes, will benefit disproportionately as the industry continues to shift toward value-based care. Pharma and medtech companies can look forward to delivering not only immense benefits to patients but also very healthy investment returns to shareholders.