Digital services are the face of modern government, and great digital services can build trust with citizens. Too often, however, failures in such services erode trust in public institutions.

One frequently overlooked cause of subpar digital services in the public sector is the way they are funded. Annual budgeting cycles, detailed business cases, and capital-spending policies clash with contemporary digital delivery methods and architectures. Governments cannot engage effectively in digital transformation without addressing funding reform.

Just as most digital projects benefit from agile ways of working, they also benefit from more agile and flexible funding models. Such funding of digital projects moves away from the false certainty of business cases, rigid budget cycles, and high-profile announcements. It encourages the development of products that better meet citizens’ needs, reduces the risk of cost overruns, and allows more frequent announcement of achievements. Digital funding can be transformative. Investments demonstrate their value early, and so are less risky; teams are empowered; citizens receive faster and better service; and governments can respond more swiftly to changing priorities and evolving user needs.

This new approach, which is based on industry best practice, is novel but not unprecedented in the public sphere. Both the Government Digital Service (GDS) in the UK and the most populous Australian state, New South Wales (NSW), have adopted it, and the US has launched the Technology Modernization Fund with similar goals. (See “Stimulating Growth in New South Wales.”)

Stimulating Growth in New South Wales

NSW had already established Service NSW, which introduced several user-friendly applications with a common username/password sign-on. But Dominello thought more was possible. He identified the funding and governance model as a key barrier to improving government services. The model did not recognize the changing needs of the public or the importance of accounting for new ideas and feedback during the life of a project. It also assumed that legacy technology remained effective. It was disproportionately oriented to the long term—five to ten years. The expectations of individual agencies, rather the needs of citizens, drove the process. Agencies assembled teams and then disbanded them, leading to the loss of valuable skills and knowledge.

Dominello tasked the government’s chief information and digital officer, Greg Wells, to design a new model to address these shortcomings, accelerate digital investments, improve services, and increase transparency.

The new model changed NSW’s digital funding in three critical ways:

- It released funding in smaller increments tied to progress toward specific outcomes, thereby reducing risk and encouraging agile behavior.

- It transitioned from funding multiyear projects to funding persistent teams that delivered end-to-end customer journeys.

- It reformed governance to focus on outcomes.

A ministerial-level delivery and performance committee and an existing expenditure review committee of the Cabinet govern the Digital Restart Fund. The committees demand that funding improve customer outcomes, and they release new funding only in response to demonstrable progress toward those improved outcomes. The initiative started slowly in 2019 but grew rapidly as part of COVID-19 recovery efforts that the government undertook in mid-2020. Its small initial budget was expanded to AU$2.1 billion, spread over four years.

Dominello says that changing the culture was the biggest challenge, but a series of quick wins helped make that shift happen. The Service NSW digital platform enabled the quick rollout of new products and services, such as digital hospitality vouchers issued during the pandemic. With previous innovations such as digital driver’s licenses already in place, the NSW government was positioned to respond promptly to citizens’ needs as the pandemic continued, such as QR code check-ins for contact tracing. Dominello also used social media channels to announce incremental but useful service improvements, including critical public health measures such as digital COVID-19 venue check-in.

His advice to other governments: Focus first on security and ethics, and then on benefits. If an initiative suffers a cyber attack or is vulnerable to bias introduced by artificial intelligence, citizens will distrust it. Finally, even if long-term plans are grand, start small.

Funding Is Broken

Traditional government funding of IT projects does not work. Research by the Standish Group shows that only one-fifth of government IT projects were successful and that success rates fall with increasing size and complexity.

Since 2012, many governments have adopted digital ways of working, but these digital initiatives remain prone to failure. In 2012, the UK created the GDS specifically to improve the government’s technological performance. Other nations have launched similar efforts, but these have done little to improve the odds of success. (See “Building Momentum in the UK.”)

Building Momentum in the UK

In its early years, the GDS replaced hundreds of existing websites with a single, user-friendly platform that was substantially cheaper to operate. It used surplus funds to accelerate new services without having to run the bureaucratic gauntlet or go through a lengthy business case approval process. The more money team members saved, the more they could do—so they had an incentive for delivering efficient outcomes. The GDS ultimately delivered better services than before and saved £4.1 billion between 2011 and 2015.

The GDS also introduced a new approach to governance. The Digital by Default Service Standard (now known as Government Service Standard) created a new benchmark for government agencies to use in gauging whether a service is good enough to launch. The standard established a life-cycle model that emphasizes such practices as starting small, understanding and validating user needs, working iteratively, clarifying policy outcomes, understanding risks, and prototyping solutions.

Members of the GDS then worked with colleagues at the UK Treasury to streamline the business case approvals process for smaller projects, giving departments leeway to use their existing budgets to fund early development work without first completing lengthy approval processes. The team also developed user insights and created technology prototypes rather than relying on the sort of abstract analysis that many business cases require.

Many departments across the UK government have taken advantage of this approach to lower the risks associated with their efforts. Even so, further financial reform is necessary to deal with other issues:

- Departments may not have the funding flexibility to work on new initiatives.

- There is no new mechanism for sustained funding of live services that still rely on annual department budgets to maintain and improve what they have.

- The Treasury’s policies regarding capital and operating expenses remain unchanged, limiting the freedom of service teams to rely on cloud architecture.

The UK has begun the work of unlocking new funding models that are more appropriate for digital products and services. More work must be done, however, to perfect these practices and apply them at scale.

In many instances, digital government initiatives fail because the government’s financial departments and treasuries do not fully understand digital ways of working. Financial practices in the public sector have changed little in decades. When governments create fast, adaptive digital teams, those teams come up against slow-moving, rigid financial processes, creating friction.

Traditional funding models are a predictable feature of digital project failures in the public sector for six reasons.

Governance and funding do not support digital delivery. Government IT projects generally receive funding in the form of time-bound allocations supported by a business case and approved during an annual budget process. Most major funding decisions occur before the start of an initiative. The senior officials within the treasury and finance ministries who are responsible for giving the final sign-off on budget allocations often have no ongoing involvement in the work itself. This system is fraught with problems:

- Once the money is allocated, further financial scrutiny is rare. If a cost overrun occurs, the sunk cost fallacy often leads to additional spending.

- Teams are not rewarded for finding leaner ways to deliver the same outcomes, for returning unused money, or for redirecting money to more pressing issues.

- Business cases project a level of certainty about the future that is unrealistic. Good ideas, new information, and greater clarity about needs can reasonably change the original case, but teams rarely have the authority to correct course.

Funding announcements set unrealistic expectations for digital teams. A government initiative commonly starts with political leaders announcing the allocation of funding as evidence of their intent to address a challenge. Expressing that intention is important and necessary. But trust in government erodes when leaders fail to deliver on their promises.

Government officials often prepare funding announcements in isolation, without the benefit of digital and technology expertise, user research, or prototyping—capabilities that are essential to the successful deployment of digital services. Policies developed in isolation from the real world may lock teams into specific technologies or methodologies even when better approaches may be available. Simply announcing the allocation of funding to a presumed solution can lock operational teams into delivering the promised solution rather than the best outcome.

Digital is treated as overhead, rather than as a strategic investment. Digital initiatives commonly proceed only if they can save cost. When planners view IT as a cost center, they focus on cost minimization rather than value creation. Goals of delivering better services, such as improved mental health or access to justice, become secondary.

Digital services have a complex cost profile that rarely receives proper management accounting treatment. Some services, such as a new digital offering, may add cost but create new value. Some digital services are less expensive than the manual processes they replace. And some digital services replace more expensive legacy digital services. In other words, the goals of a healthy digital portfolio may range from strategic investment to tactical cost reduction.

Siloed funding inhibits cross-agency collaboration. Delivering a multi-agency initiative requires collaboration—joint teams, clarity about funding and accountability, and a single governance structure. Too often, however, “Conway’s law” prevails: services mirror the current structure of government rather than the requirements of the problem to be solved.

Governments have limited options for reshaping the internal boundaries of their organizations. In the criminal justice system, for example, a defendant moves through a labyrinth—from policing, to prosecution, to the courts, to incarceration, and back to society. Agencies involved with mental health, child protection, disability, housing, and employment may also be involved with the individual’s journey through the system. Most governments struggle to coordinate across these agencies.

Solutions to this challenge require funding that cuts across institutional boundaries, but this is hard to achieve. Citizen-centered, cross-agency initiatives with a positive cost benefit often get stuck in the machinery of government, buried by multiple agencies’ governance requirements or undermined by uncertainty about their longer-term home.

Traditional portfolio funding of separate parts of government with separate allocations of money also limits the ability of teams from different departments or different levels of government to share a common platform. As a result, shared horizontal platforms remain rare in government.

Siloed, risk-averse funding inhibits experimentation. Traditional funding does not support or facilitate experimentation. Incubator or catalyst funding, for example, encourages the creation of products that evolve throughout their development. The GOV.UK Notify platform, which initially focused on tracking government transactions, offers a striking contrast. Free to experiment, the team discovered that sending out push notifications about the status of transactions was a bigger need than simply tracking them, so it shifted course.

Existing approaches are ill suited to a changing environment. As the pace of change in the world accelerates, governments need to respond swiftly today while also developing resilience so they can respond tomorrow, too. Traditional government finance and project management practices, however, are stage-gated, sequential, and inflexible. These practices struggle to accommodate change and mesh poorly with the rapid feedback cycles and flexibility that are essential in building digital services.

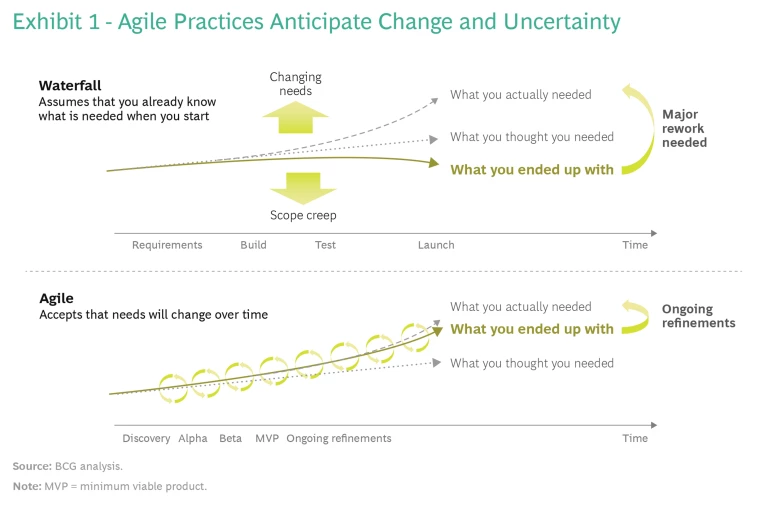

For most digital projects, agile ways of working have proved to be a less risky approach than the traditional, sequential waterfall method of development. To accommodate uncertainty, agile methods use a customer-centric DevOps approach and create fast-feedback loops that allow adjustments. (See Exhibit 1.)

Agile practices and teams have improved the delivery of government services. But without a reformed funding model, agile runs into brick walls. The upfront cost of continuing to fund and govern as usual will become an increasing liability. Projects will continue to run late, exceed budget, and fail to meet expectations. Poor project outcomes lead to poor experiences, as citizens resort to phones, in-person visits, and even mail to obtain public services that should be available through digital channels.

All Government Leaders Need to Embrace Digital Funding Reform

Although funding for digital projects affects a broad array of public sector leaders–agency heads, CFOs, CIOs, and many others—few of them consider financial reform a priority. But funding reform is necessary if governments are to realize the full potential of digital technologies.

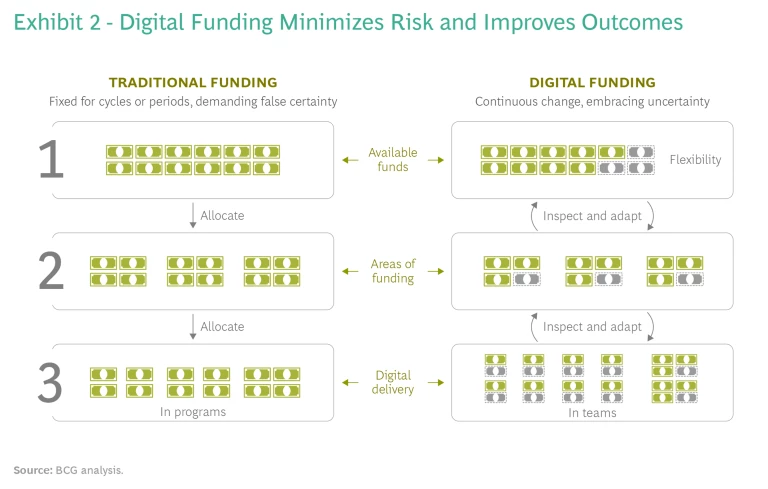

Reformed funding of digital projects should support digital ways of working and recognize digital’s transformative potential. It must be flexible but also rigorous and open to scrutiny. (See Exhibit 2.) Some key shifts in culture, attitude, and behavior are necessary.

Fund less, but fund more often. Digital funding needs to match more closely the rhythms of digital delivery. Smaller and more frequent releases of funding can help ensure that teams stay on track and that those in need of fresh funds to support innovative work do not have to wait for the next budget cycle. The US Congress passed a law in 2017 that facilitates this sort of funding flexibility. Although reform efforts started slowly, recent changes in the law may accelerate digital funding practices. (See “Modernizing Tech Funding in the US.”)

Modernizing Tech Funding in the US

In 2017, the US Congress passed the Modernizing Government Technology (MGT) Act, which aimed to create greater funding flexibility so that agencies could engage in multiyear digital transformations without repeatedly having to seek new funds through traditional annual budget cycles. The MGT Act created the Technology Modernization Fund (TMF) with a modest initial funding amount of $100 million. In 2021, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan (ARP), which, among other things, increased the TMF’s funding to $1 billion.

Prior to this year, agencies had to repay TMF loans within five years. Now, the TMF has greater flexibility in determining whether the loans need to be repaid in full. This shift, prompted by the need to accelerate the pace of modernization in the face of the pandemic, has increased interest in the program. As of July 2021, the TMF had received more than 100 proposals totaling $2 billion in requested funds.

The TMF board evaluates several factors in deciding whether to approve an agency’s application for funds:

- The impact on the agency’s mission, including improving service delivery and security, reducing operational risk, or addressing urgent consumer pain points

- The agency’s digital maturity and the role of the investment proposal in accelerating the agency’s IT modernization

- The feasibility of the project, including team strength, executive visibility, and support

- Expected cost savings or lasting positive financial impact

- The agency’s ability to use common solutions such as government shared services, reusable technology from existing agency products, or off-the-shelf software

- Potential reduction or retirement of outdated, legacy systems in favor of modern scalable technology platforms

The TMF board conducts detailed reviews with project teams and executive leadership before approving funding. It reviews the status of investments quarterly to ensure that the agencies are meeting their plan. Technical experts are available to support project teams.

Agencies have tapped into the fund to improve public services and internal operations. For example, in 2018, the Department of Agriculture used a TMF loan to consolidate and modernize ten public websites into farmers.gov, resulting in improved, centralized services such as financial assistance and payment. The Department of Labor led a multi-agency effort, which also began in 2018, to streamline and digitize the US visa application system for employers.

Announce more achievements and fewer intentions. Breaking up large projects into smaller and more frequent releases allows leaders to focus public attention on the actual delivery of features and functionality that benefit citizens rather than on big spending commitments that fail to deliver. Regular delivery of results builds trust in public institutions and increases accountability.

Regularly review every part of the budget. Digital funding may seem out of place in the traditional world of public funding. Its emphasis on funding individual projects in smaller, lower-risk increments is hard to square with the need for high-level scrutiny and oversight. One way of dealing with this mismatch is to adopt a model that scrutinizes both project funding and business-as-usual funding so that officials are regularly rebalancing and reprioritizing funds strategically.

In some US government agencies, the IT operating budget may consume up to three-quarters of the agency’s overall IT budget. By evaluating existing spending and operational risk, governments may be able to redeploy funds from lower-risk, business-as-usual activities to support critical digital projects that would otherwise go unfunded.

In the US government funding process, when agencies receive incremental dollars to support a key technology initiative, they are often expected to demonstrate fiscal prudence by contributing materially to a project from their existing budget. A process that questions business-as-usual funding, if done well, can support such requests for agencies to have skin in the game.

Fund persistent, mission-centered, multidisciplinary teams. Organizations commonly fail to recognize the permanence of change and the need for permanent teams. Success accumulates continuously over years or decades, but most digital teams are temporary and under constant threat of disbandment. To encourage teams to become successful, capable, and experienced, agencies must fund them more sustainably, with both core funding to encourage longevity and burst funding to accommodate temporary expansion or expertise.

The model that brings these ideas together is the persistent, mission-centered, multidisciplinary team. Such a team combines several valuable features:

- Persistence allows people working closely together to become more effective. Over time they build better relationships, adapt internal processes, and learn how to deliver faster, higher-quality services. Iterative funding helps reduce the impact of funding allocations on teams.

- A mission gives teams the freedom to experiment and adapt without traditional constraints. Teams are free to adopt new approaches as long as they accomplish their mission.

- A multidisciplinary approach ensures that teams have the skills they need in order to deliver. Teams can reduce the feedback loops for designing, making, testing, and operating technology from days or weeks to minutes because representatives from each relevant field are on the team.

Build modern governance and management practices. Governance should accelerate progress and reduce delivery risk. It should also provide teams with the context and insight necessary to make consistent, transparent decisions that align with overall strategy.

A governance model that supports digital funding has five key characteristics:

- A clear definition of the problem and desired outcome

- An approach that focuses on empowering teams to come up with solutions

- Senior-level sponsorship and input into funding decisions

- Frequent funding decisions

- Flexibility to redirect funds and teams to other priorities

These characteristics enable teams to experiment and then to choose a direction on the basis of evidence that it works. They also encourage teams and individuals to be open and honest and allow uncomfortable truths to emerge. The rationale for funding decisions relies on data and experience rather than assumptions and norms.

Encourage emerging and experimental practices. Teams that repeatedly face the same problem will often find creative solutions if they have the autonomy to experiment and the freedom to fail. Return on investment is volatile for experimentation; it may be high in some cases and zero in others. This is the nature of venture capital and other forms of private-sector funding. The public sector cannot expect to achieve digital innovation without putting some money at risk. The current approach of minimizing short-term risk on every initiative creates long-term risk by stifling innovation.

Governments should create a portfolio with a balanced range of approaches to spread their risk, and they should ensure that planners view every initiative—whether successful or not—as an opportunity to learn.

Embrace cloud technology and a little opex over a lot of capex. Data centers, corporate networks, and complex hosted systems such as enterprise resource planning systems and customer relationship management systems are expensive to create and maintain, and they require specialized skills and knowledge. Today, organizations can obtain these commodity systems as cloud services. The range of available open-source, off-the-shelf, and X-as-a-service offerings that meet government needs is rapidly increasing. Moving from owning computing resources to renting them entails making a corresponding shift from capital expenditure to operational expenditure. But many government budgeting processes have an implicit or explicit preference for one-off capital expenditure and asset ownership over commitments to ongoing operating expenditures. Governments need to eliminate any bias for capex, and they should encourage greater use of configurable solutions that get the job done over unnecessary customer and bespoke software.

Existing patterns of funding, approvals, and governance pose major challenges to digital delivery today. In response to these difficulties, a few governments have begun to explore new approaches. They recognize that digital services are central to citizens’ experience of government and are vital to citizens’ trust in public institutions. Even so, today, such approaches remain rare, experimental, or exceptional. In order for these approaches to reach scale, government finance departments and treasuries must make them part of the financial governance toolkit.

Digital professionals and financial professionals within the government must partner closely, as both bring valuable perspectives to the table. Digital transformation cannot occur without financial reform. Financial and digital leaders can work together to simplify and speed up approvals processes and to support teams that are on board with the digital funding approach.

Reforming digital funding is not without risk, but it’s a challenge that governments must embrace boldly and openly if they are to be the effective, trusted institutions we need.