This report is the first in a series that explores the innovative potential arising from the global movement of skilled workers and examines the implications for CEOs and policymakers.

We’re often led to believe migration is a drain on the country’s resources, but Steve Jobs was the son of a Syrian migrant. Apple… only exists because they allowed in a young man from Homs.

– Banksy

Apple’s iPhones, Tesla’s cars, and Pfizer’s RNA-based COVID-19 vaccines are some of the everyday innovations that change our lives for the better. But they carry a greater significance as well. Each one was conceived by a small team of boundary-breaking inventors who share something in common: these innovations were driven by immigrant founders—people who had crossed physical borders before advancing the boundaries of what’s possible for all of us.

Of course, the migration of creative geniuses has been a global phenomenon for centuries. Inventor Galileo Galilei and composer Frédéric Chopin, for instance, moved to Florence during the Renaissance and fin de siècle Paris (respectively) not only because those cities were hubs of commerce but because they were also melting pots of people with bold ideas.

Humans cross borders, and humans create boundary-breaking innovations. Could it be that those two events are intricately linked and generate opportunities—in terms of both economic value and human values? We think the answer is yes, which raises the next questions: What if we could develop strategies to tap into and share these opportunities? Which legitimate concerns would we need to address? And which long-held beliefs would we need to reconsider before starting the journey?

Migration Impacts Innovation, Growth, and Culture

Humans crossing borders invariably create global networks. By migrating, people connect the new contacts they form in their destination countries with the ones in their communities of origin. Seen from this vantage point, people do not merely leave one country and arrive at another; they bridge the two. This matters because networks are powerful conduits of capital, knowledge, ideas, and ideals.

When people migrate, they do not merely leave one country and arrive at another; they bridge the two.

The economic and social impacts arising from these global networks have been well established by academics and studied by practitioners, but they are not yet widely known. (See “Definitions.”)

Definitions

- Generation: first-, second-, and third-generation migrants

- Education: with or without some college-level education or vocational training

- Intent of movement: humanitarian, study, work, and family unification

- Duration of time abroad: short-term relocation (brief travel or temporary move) and long-term relocation (permanent move)

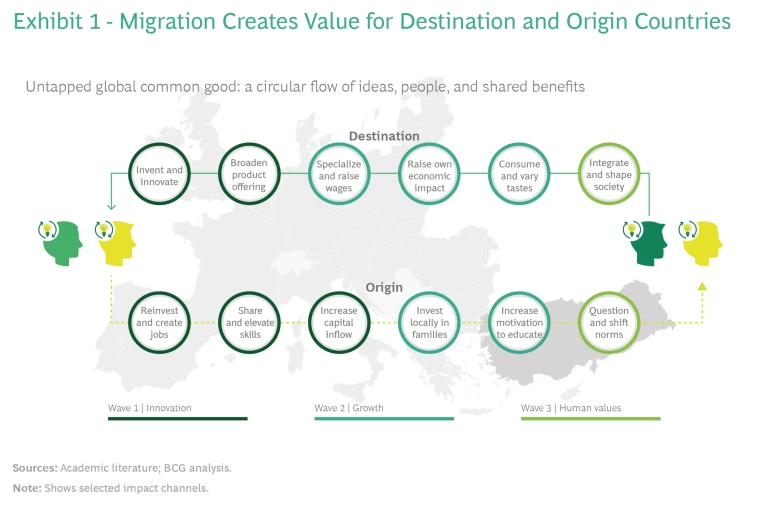

We explore the ripple effects of these impacts, wave by wave, in broad strokes, while keeping in mind that the reality and perception of global migration depend on context and are multifaceted. (See Exhibit 1.)

Innovation

In the first wave, immigrants drive innovation in both destination and origin countries. The extent to which this happens varies greatly across countries, but it’s fair to say that most places see a gap between the promise of such induced innovation and its realized potential.

Destination Countries. Immigrants drive innovation either directly, through entrepreneurial or inventive activity, or through their close collaboration with native workers in companies of all sizes. As the global leader in attracting skilled foreign talent, the United States provides a good magnifying glass to examine migrants’ entrepreneurial and inventive activity.

On the company level, 45% of all Fortune 500 companies were founded by an immigrant or the child of an immigrant, and 50 out of 91 startup companies worth more than $1 billion had at least one immigrant founder. As of today, more than 3 million immigrants (skilled and unskilled) have become entrepreneurs, creating a total of 8 million

Indeed, immigrants tend to increase productivity in most countries around the world, largely because of the diversity of perspectives, experiences, and ideas that they contribute when working closely with locals in companies in their destination countries. These innovation-inducing effects are mostly—if not exclusively—driven by skilled talent.

In addition to driving innovation, immigrants also trigger innovation by increasing the spectrum of consumer tastes and needs that companies can serve. The story of Richard Montañez, a PepsiCo janitor and the son of a Mexican immigrant, illustrates this nicely. Following the temporary breakdown of a machine that dusted the cheese-flavored snacks the company made, he added flavors inspired by Mexican street food to the bare chips—and instantly realized he was on to something. Recognizing an opportunity to create a product that would appeal to his own demographic, he pitched his idea to the CEO of PepsiCo and thus invented a best-selling snack, Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, which has since grown into a multimillion-dollar franchise for PepsiCo.

Origin Countries. Migrants also generate powerful, yet largely overlooked, innovation effects in origin countries. Leveraging global networks, migrants often reinvest capital in, and transmit productive ideas to, their countries of origin. Migrant diaspora networks can thus drive capital accumulation, innovation, and catch-up growth in origin countries.

The IT industry in India, for instance, owes its existence in no small part to Indian-born talent that returned home after education and work abroad, notably in the US. Consider Faqir Chand Kohli. After obtaining a degree from MIT and working in Boston, New York, and Canada, he took the lead at Tata Consultancy Services, building it into India’s largest IT service company.

India’s universal digital-passport system Aadhaar, a vast digital database powering government and private-sector services, is another example. The system was conceived by a team that returned to India from Silicon Valley under the project leadership of Nandan Nilekani, a cofounder of Infosys. Similar stories abound about the tech industry in other countries as well, including Egypt and Nigeria. They also arise in the automotive industry—in Turkey and Vietnam, for example.

These stories are not just anecdotal. There is clear causal evidence that countries tend to develop new companies and industries as a direct result of having created migration networks with people in places that already possess the latent knowledge required to build such value-creation steps. In other words, a country is much more likely to start producing a certain product from scratch if a destination country of its emigrants excels in producing that product. Especially skilled migrants reduce transaction costs between their host and home countries by creating two types of channels. The first is an information channel that allows for an increased flow of goods and foreign direct investment. The second is a knowledge diffusion channel, whereby emigrants convey such assets as technological knowledge, norms, and know-how, thus fueling homegrown production.

Growth

In the second wave, we see broader economic growth effects beyond those achieved directly through innovation.

Destination Countries. Immigrants in destination countries constitute a sizeable work force. They fill labor shortages and, perhaps counter-intuitively, drive up wages for domestic workers. Working for wages many times higher than those in their origin countries, migrants create significant demand for goods and services, thus fueling economic growth in destination countries. Strikingly, migrants also tend to moderately increase the wages of the locals they work with. Because more diverse teams are often more productive, they tend to bump local workers into communication and oversight roles, which are usually better compensated. While there are certainly instances of job competition between native workers and immigrants at the lower end of the skill spectrum, the overall effect on job creation and wage levels tends to be positive.

Origin Countries. Just as in the first wave, positive effects of migration also emerge in origin countries. Direct cash remittances are the most well known: in 2020 alone, migrants sent home $660

What’s more, successful skilled emigrants often serve as role models in origin countries—a phenomenon that showcases the value of education. This increased perception of value motivates families and individuals to make deeper investments into education, which leads to a better-educated population—which, in turn, increases economic growth.

Culture

In the third wave, migrant networks can be conduits of social norms and values. Yet, while migrants certainly influence the cultures of destination countries, they seem to create a more significant impact on the cultures of origin countries. Consider author and human rights activist Zahra Hankir, for example, born in Lebanon and educated in Beirut, Manchester (England), and New York. Upon the publication of her book Our Women on the Ground: Essays by Arab Women Reporting from the Arab World, she was seen as one of the early proponents of women’s rights, giving a voice to an often-unheard segment of the population. Migrant networks have shown the potential to promote democratic norms in origin countries because destination countries have higher rates of democratic participation and greater gender equality.

A Vision of Prosperity and Peace

So, what would happen if more people crossed borders? Excitingly, this is not only a question of economic value but also one that touches on human values.

Economic Value

We live in a world in which the movement of people is much more tightly restricted than capital and goods are. As a result, the number of people around the world who would like to move and work abroad , if they could, is vast: from 750 million to 2.5 billion people, or about 50% of all people of working age.

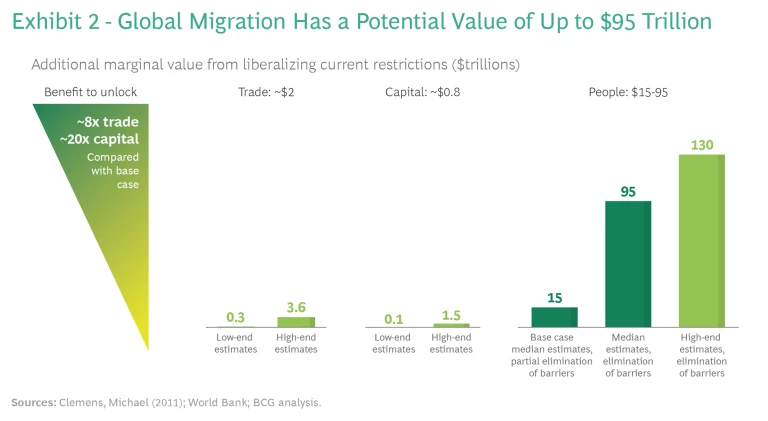

From a purely economic point of view, removing a restriction—even one that was introduced with the good intention of protecting local markets—is bound to increase overall economic output. (This is the reason countries agreed to remove many limits to trade and capital flows.) The question then is, by how much would that output increase?

The estimated numbers are extraordinarily large. If, theoretically, all restrictions to labor mobility were removed, then the world could see an increase in global economic output of up to $95 trillion per

Human Values

Is a world that tightly restricts the movement of billions of people a just world? What is clear is that origin matters much more than it used to centuries ago, thanks in large part to the Industrial Revolution. Today, about two-thirds of all economic differences between any two randomly chosen human beings on the planet can be explained simply by asking one question: Where were you

The simple act of crossing borders offers the dual promise of global prosperity and peace.

Philosophers may disagree about whether notions of fairness and solidarity that apply on a national level can be extended to a global level. However, the fact that birthplace largely determines a person’s economic life trajectory is—and feels—arguably unjust for those on the losing end of the spectrum. Migration, therefore, reflects the choice of an empowered individual to reject the lottery of life at birth and move to a place that promises opportunity. People who vote with their feet can challenge and put limits on the power of nation states, which are the ultimate actors in the arena of global public policy. This explains in part why countries have been hesitant, unlike on trade, to pursue a global agenda on this matter.

Migration is therefore a direct way to advance equality of opportunity for individuals. But global migrant networks have another intangible benefit on an aggregate level: they build mutual dependency and thus contribute to a more interlinked, peaceful world built on shared interests.

The seemingly inconsequential act of crossing borders thus holds a dual promise that intricately links both economic value and human values: global prosperity and peace.

Challenges and Constraints

Today, this dual promise seems far out of reach. Global migrant networks are relatively small in size, their immediate benefits are unequally distributed, and views on the merits of migration are politically polarized and highly contested.

Small Size

In what may be a surprise to residents of such metropolises as Berlin, New York, Paris, and Shanghai, global migrant networks are not very large in size. In 2020, only around 3% of the world’s population, or about 200 million people of working age, lived in countries other than where they were born (this figure even includes the millions of post–Soviet Union residents). Of those, only about 50 million people are skilled, which means that one of every four global migrants has at least one year of university-level education.

To put these numbers in context, let’s compare them with global trade. As a share of world GDP, global trade has increased by about 20% since 2000 and remains at high levels: $53 trillion, or about 60% of world GDP, in 2020. In contrast, global migration flows as a share of global population have stagnated since 2000. Despite an increase in absolute numbers (from 25 million in 2000 to 35 million in 2020), even the fastest-growing segment of international migrants—skilled inflows to OECD countries as a share of the skilled population—has declined in relative terms since 2000.

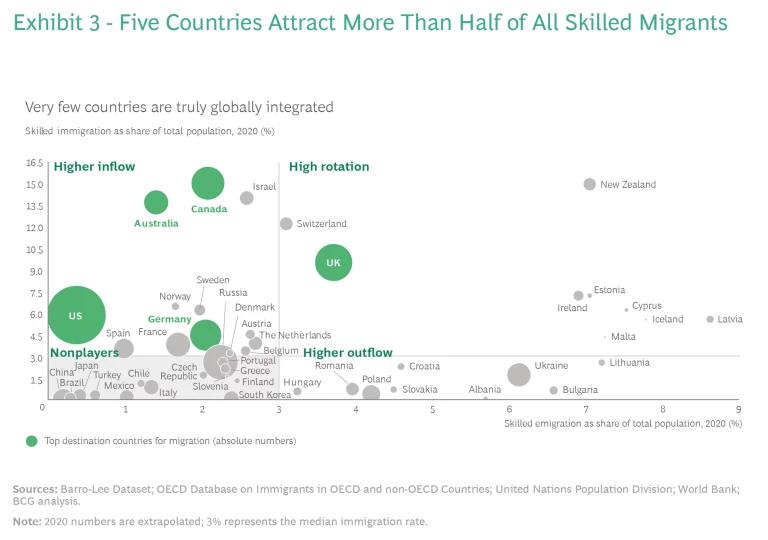

Unequal Distribution

Globally, five countries have attracted more than 50% of all skilled immigrants in the past decade: in descending order, they are the US, the UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia. Meanwhile, skilled emigration is becoming ever more widespread as more people gain digital access and achieve the financial means to move. As a result, about 25 countries have a surplus of skilled talent, while at least 64 have a deficit. Interestingly, some countries—including Brazil, China, Japan, and South Korea—are far less integrated into the global flow of talent than one would expect, given their level of development.

While global migration flows have the potential to generate circular benefits, it’s clear from these numbers that countries and companies start off facing vastly different conditions and a very unequal playing field. (See Exhibit 3.)

Within countries, a similar unequal picture emerges. Skilled talent tends to cluster in large cities (even though the numbers have probably decreased as a result of the pandemic). This is especially true for skilled migrant talent, where the top three largest cities reliably attract more than 50% of skilled

Polarized Positions

Global migration flows are inherently fragile. This may be surprising because public support for immigration has been steadily increasing in many countries, including Europe and the US, since 2000, reflecting a generational change in a wide set of attitudes. Support for skilled immigration is even higher—at 78% or more—for the top receiving countries: the US, the UK, Germany, Canada, and

However, these averages hide considerable polarization along political party lines between the left and the right. As a result, governments can find it politically advantageous to enact immigration policies that do not fully reflect the will of a majority of voters. Over the years, such polarization can lead to wide variations in the development and execution of migration policy, especially in two-party systems, thus driving political uncertainty.

Contested Views

Why does migration polarize voters so much? People’s support or resentment for migration correlates with how they perceive their own economic outlook and social status, and with their level of concern for border security, cultural cohesiveness, and the implications for fiscal balances.

While it’s natural for people to see immigrants as potential rivals in the struggle for jobs or government support programs, the data tends to show that immigrants actually create jobs and—with few exceptions—raise local workers’ wages. Effects on fiscal balances can be positive or negative depending upon the demographics of migrants as well as their employment status. Due to constraints in the availability of data regarding some countries, the facts for North American and a few European countries tend to be much better understood than for other regions, and lessons from one context are not easily applied elsewhere.

But economics isn’t everything. Trade, technology, and the quest for sustainability change the job profiles of millions of local workers and, as a result, profoundly affect our notions of social status and societal appreciation. Therefore, policies on these matters, and on migration, must also address the urgent need for upskilling, economic support, and the social elevation of those who contest these changes.

Three Fresh Perspectives

Let’s zoom out. If the inherent promise of global migrant networks is so big, and the reality so wanting, why is there no action on this front? Why is there no discernible joint agenda, however loosely coordinated or defined, that aims to embrace this potential while respecting voters’ concerns, worries, and fears?

Evidently, formulating such an agenda is difficult—and is made even more difficult because of countries’ different starting positions and values. What’s more, given that there is no globally recognized institution with a mandate to propose a way forward, developing such an agenda will require leadership from within the system. Complicating the creation of a harmonized policy agenda even further, migration involves people with varying levels of education who choose to move because of many reasons: to flee from warfare, to reunite with families abroad, to study, or to work. And that raises perhaps the most striking point: though the group of skilled people who move for work is the least politically polarizing group of migrants, no agenda exists to tap into the potential that they offer.

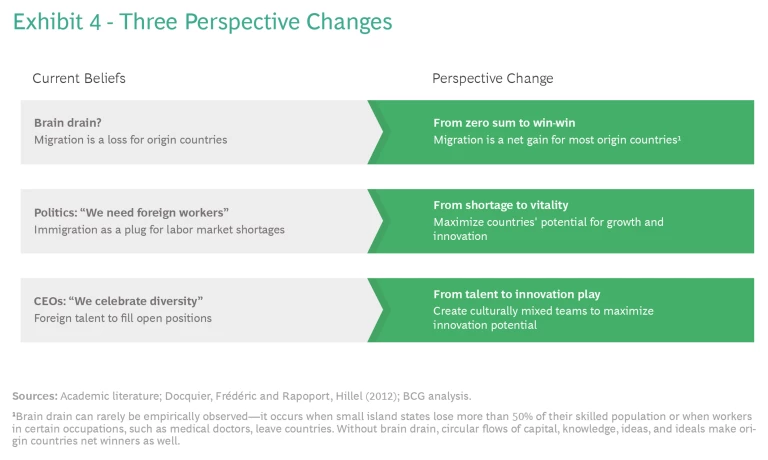

Why is that so? In the societies and companies that are already most open to skilled migration for work, we often come across three basic common beliefs:

- All: “What’s a brain gain for us (destinations) is a brain drain for others (origins).”

- Policymakers: “We need skilled immigration to fill labor market shortages.”

- CEOs: “We see global talent as a source of advantage, and we celebrate its diversity.”

All three of these statements contain a grain of truth. Yet they are also incomplete because they prevent us from grasping the true strategic potential. We base this view on our own research; on discussions with leading academics in the field, policymakers, and CEOs; and on our experience in building digital solutions that support the bridging of continents by global talent to fuel corporate innovation. (See “For Further Reading.”)

For Further Reading

For a discussion of the total economic value of migration, read Michael Clemens (2011), “ Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?,” Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 25, Number 3, 83-106.

A landmark overview article on brain drain was published by Frédéric Docquier and Hillel Rapoport (2012), “ Globalization, Brain Drain, and Development,” Journal of Economic Literature—Volume 50, Issue 3, 681-730.

Dany Bahar and Hillel Rapoport document evidence for the diffusion of knowledge from migrant diasporas back to origin countries (2018), “ Migration, Knowledge Diffusion and the Comparative Advantage of Nations,” The Economic Journal—Volume 128, Issue 612, 273-305.

For a deeper understanding of how skilled immigration positively influences US technology formation, read William R. Kerr and William F. Lincoln (2010), “ The Supply Side of Innovation: H-1B Visa Reforms and US Ethnic Invention,” Journal of Labor Economics—Volume 28, Issue 3, 473-508.

Read Alberto Alesina, Johann Harnoss, and Hillel Rapoport to explore how the diversity of origins causes economic growth through innovation (2016), “ Birthplace Diversity and Economic Prosperity,” Journal of Economic Growth—Volume 21, 101-138.

To understand the effects of immigration on the wages of local workers of all skills, read Gianmarco I. P. Ottaviano and Giovanni Peri (2012), “ Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages,” Journal of the European Economic Association—Volume 10, Issue 1, 152-197.

Alex Nowrasteh and Benjamin Powell have written an extensive account on immigrants’ influence on political and cultural institutions in destination countries (2020), Wretched Refuse? The Political Economy of Immigration and Institutions, Cambridge University Press.

Mathias Risse explores the questions of global equality and justice arising from limits on the global mobility of workers in his book (2013), On Global Justice, Princeton University Press.

Let’s evaluate each belief in turn. (See Exhibit 4.)

All: From Zero Sum to Win-Win

Worries about brain drain are the number-one reason why leaders do not actively embrace the movement of skilled people but take a reactive approach

It’s true that excessive emigration of skilled workers at levels greater than roughly half of the entire population can be harmful to origin countries. Encouragingly, only 12 of 195 countries, typically island states in the Pacific or Atlantic oceans, see such elevated levels of emigration. It’s also true that the emigration of workers in certain occupations, such as medical doctors, is a clear net negative for origin countries—especially if they have a shortage of such workers. Fortunately, these occupations can be precisely defined and are also a small share of all skilled workers.

As a result, the emerging consensus among academics is that skilled migration is rarely a brain drain and can be structured in a way as to become a win for all parties involved. This is mainly because of the previously overlooked large, positive innovation- and growth-stimulating effects of skilled diaspora networks sending capital, knowledge, ideas, and ideals back to their origin countries.

Consequently, we should see skilled migration not as a game of winners and losers, but as one in which all can win—like global trade. This change in perspective would give leaders in both destinations and origins the headspace to shift their approach. They could thus move away from tactical responses and toward strategic approaches to jointly shape the opportunity.

To embark on this agenda, the key question to explore is, What exactly makes border-crossing valuable, and how can the sharing of benefits by both destination and origin countries be ensured?

Policymakers: From Shortage to Vitality

Many policymakers in OECD countries proclaim that skilled immigration is the answer to labor market shortages. While well intended, this viewpoint is incomplete and thus ineffective. Here’s why.

First, a labor market shortage today may be a surplus tomorrow. Due to technological and social change, jobs that urgently needed to be filled decades ago, such as those in metals and mining in Europe, are now fading away. Today’s labor market shortages in basic digital software engineering may also prove to be temporary, as artificial intelligence and no-code tools slowly but steadily become available to the general public. Second, this view is a purely resource-based, economic one. It fails to resonate with voters on an emotional level, unlike the way matters of justice and geopolitical stability do. In addition, it underappreciates the contribution of skilled immigrants, who do not just fill jobs. Rather, as they work together with native-born teammates, they generate creative surpluses that directly benefit their colleagues, their companies, and society.

Consequently, policymakers would be well advised to see the true contribution of skilled immigrants not in terms of just getting a job done but as contributing to a more dynamic, vital society. This includes immigrants’ entrepreneurial activity, direct and indirect creative contributions, and the effect on economic growth of their own domestic consumption and taxes.

The key question to explore from this perspective is, How can policymakers stimulate broad-based economic vitality, and what new policy practices could be adopted and scaled?

CEOs: From Talent to Innovation Play

The idea that global talent is a source of tactical advantage is already fully embraced in the digital and tech world. It’s also becoming more popular with established companies seeking to transform digitally. The view has clear merits, but it may overlook the broader strategic opportunity. Here is why it is incomplete.

Some leading companies today, such as e-commerce player Zalando, hire and relocate globally. Others, such as General Electric and Samsung, also engage through more flexible, virtual setups. Both practices evidently work well for companies seeking to populate hard-to-fill positions. But does this tactical advantage also work as a long-term strategy? In our experience, global talent is often more mobile than homegrown talent, so any advantages gained through availability or lower cost could prove to be only temporary.

Instead, CEOs may wonder whether there could be a much bigger, durable strategic advantage in building teams composed of talent from various countries of origin. BCG research shows that such teams produce more functional diversity, and that functional diversity not only correlates with innovation but actually causes it.

Some iconic corporate innovators today owe their inception and a share of their enduring success to their foundational embrace of a broader social purpose. Think of Patagonia, for example, which was established in 1973 with the clear intent to protect the environment. Or Tesla, a company that, through its own investments and boundary-shifting storytelling, is credited for advancing the electrification of mobility by two to three years. Is it conceivable that one day we will see companies strategically embracing the cause of global equality?

The key question to explore is, Why does it matter for CEOs, for which businesses in particular can it become a source of strategic advantage, and what can leaders do now?

Actions for Leaders

We propose that CEOs and policymakers take four actions now, in order to tap into the large potential created by humans crossing borders:

- Start from the top. Begin by focusing on migrants who have either a university education or vocational training—even though it’s not easy to do, in practice, and it limits the overall promise. Because this agenda will affect at least 1.9 billion skilled people in 2050, it is both globally inclusive and one that respects legitimate concerns among vulnerable groups in destination

countries.10 10 Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (2018). In parallel, continue the urgent political and operational efforts to safeguard the livelihoods and dignity of refugees and undocumented migrants. - Create win-wins. Close the innovation and growth loops between countries of origin and destination countries by designing multilateral policies, firm engagement, and technology to digitally accelerate the circular flow of ideas, capital, and ideals.

- Strive for vitality. As a policymaker, keep an eye on today’s and tomorrow’s local labor market needs, but make sure to recognize immigrants and your own diaspora of emigrants as sources of dynamism and vitality. The diversity of immigrant inflows and of emigrant outflows then becomes a key lever to increase the innovative potential inherent in both in a politically sustainable way.

- Innovate to lead. As a business leader, recognize and act on the immediate talent advantage inherent in global talent pools—but do not stop there. Embrace cultural diversity and the functional diversity it brings to jointly solve hard problems of discovery in innovation. And if you believe that talent is universal, but opportunity is not, ask yourself whether this is a cause that you, as a business leader, would want to lead.

Time to Elevate the Agenda

The movement of people across borders is as intricately linked with human existence as is the movement of goods—trade. Yet until now, people crossing borders have received less strategic attention from the business community than the movement of goods.

As we show, people crossing borders create vast global networks that already drive innovation and growth in both destination countries and origin countries. Yet these networks remain comparatively small in size; they’re not equally distributed around the world; and voters’ support for more open migration policies remains fragile and highly contested. As a result, the latent potential to drive shared economic value and create a more balanced world based on human values remains unfulfilled.

The world needs a new engine of growth and geopolitical stability more than ever. We think it’s time to elevate the potential of people crossing borders and to explore fresh ways for governments and business to work together for the benefit of all.