The giants are on the march, and the battle is on between the global Goliaths and the local Davids in streaming-video markets around the world. With their domestic core growth slowing, international markets are more important than ever for big subscription video providers. Netflix, for example, began its international expansion in 2016, and by the end of 2020 about two-thirds of its subscribers lived in countries other than the US. In 2020, the streaming giant picked up more than 80% of new subscribers outside of the US and Canada, with 42% coming from Asia-Pacific and Latin America. Approximately 60% of Disney+ subscribers came from markets outside of the US, with Disney+ Hotstar in India and Southeast Asia making up 30% of the subscriber base.

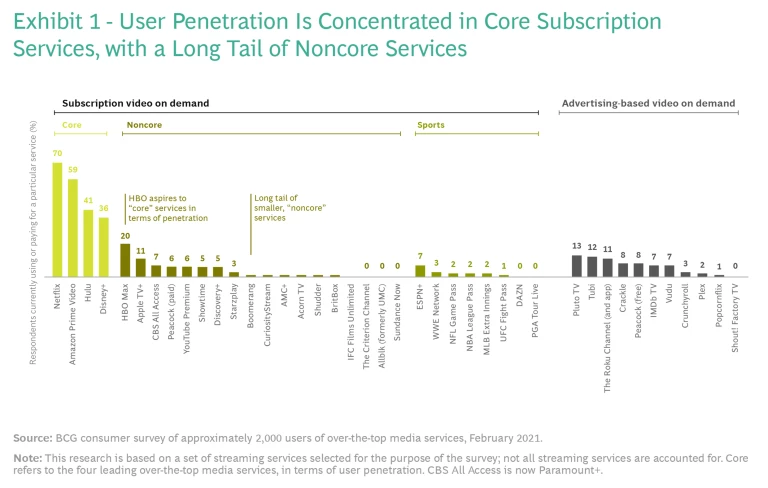

The streaming-video pattern in mature markets is well established. BCG research shows that the average consumer subscribes to two to three streaming services and that the distribution of market share among providers is consistently top-heavy. The top three or four services dominate, with user penetration of 35% to 70%. They are trailed by a long tail of mainly niche services, each with a small, single-digit share. (See Exhibit 1.) A big reason is the staggering amounts that the top players can spend on new content, the key to attracting and retaining subscribers. Combined content spending by Netflix, Amazon, and Disney+ is expected to grow from $23 billion in 2021 to $29 billion in 2025.

The question in less mature markets is whether the Goliaths will stake out similar dominant positions or whether homegrown players can marshal their own considerable strengths to attract substantial shares of local viewers. Our experience indicates that local media companies can not only compete with global giants but can play to win—if they deploy their advantages effectively. The answers to four questions, in particular, will determine local companies’ chances:

- How aligned are consumption norms in the local market with the Western-based subscription video on demand (SVOD) business model?

- How big is the need for local content in the market, and how much complexity in the content production ecosystem must international players navigate?

- How well does the content travel? Is there a risk of international attackers overinvesting in the local market’s content?

- How complex is go-to-market execution in the local market? How big a barrier to entry does it constitute for international insurgents?

Models Matter

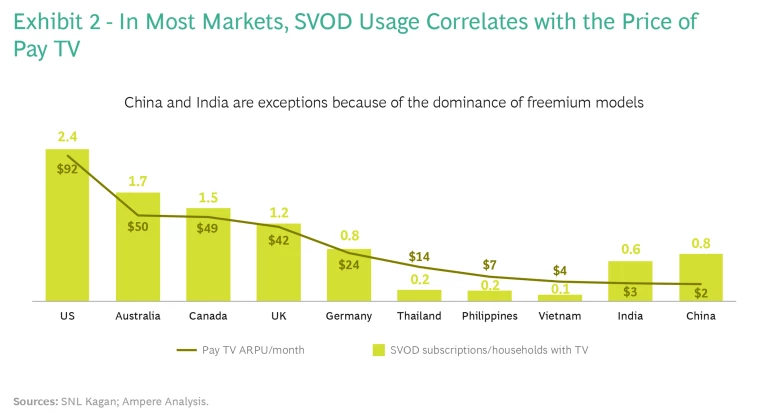

With the exception of China and India, where freemium models are popular, the success of SVOD-only models such as Netflix strongly correlates with the average revenue per user (ARPU) for pay TV in a given market. (See Exhibit 2.) Only a handful of markets, such as the US, Canada, Australia, and the UK, have so far supported substantial ARPUs. In most other markets, video services—both linear TV and streaming video—have remained predominantly advertising supported. The global giants have had to stick with their subscription-only models because of the need to cater to their most lucrative market, the US. But with ample “free” choice available, consumers in other markets are reluctant to pay for video subscriptions. This has caused the big global players to push the SVOD model in markets where it does not work well.

India has proved a tough market for global players to crack, despite lofty ambitions and hundreds of millions of dollars invested in top-end content. A big barrier for consumers has been high SVOD price points, which have turned off potential subscribers. Global providers such as Netflix have switched to rolling out inexpensive mobile-only plans in India and other markets in Asia. Meanwhile, Hotstar (now owned by Disney) has enjoyed significant success at lower ARPUs with a heavy concentration of locally relevant content, such as cricket. (Hotstar’s monthly ARPU is $0.90, compared with Disney+’s global average of $5.40, excluding Hotstar.)

Over-the-top companies in China are seeing success from a hybrid advertising–subscription model, championed by the likes of Tencent and iQIYI, which have been able to acquire more than 100 million paid users each. The approach involves building a large user base for an ad-based VOD service by making the bulk of content free and accessible using “smart windowing” to connect to the TV. Premium subscription services, such as earlier viewing for new content, are subsequently offered for a price. The freemium strategy, which shifts the value formula from paying for content to paying for not missing out, has proved successful in low-ARPU markets among consumers who do not habitually pay for subscriptions.

Consumers Want Local Content

The Goliaths have large global libraries, but success in most non-English-speaking markets depends on local content, often in local languages, built around local sensibilities and set in familiar locales. This is especially evident in national markets with diverse subcultures, such as India and Malaysia. While the global giants have expanded their content acquisition programs, their supply chains , ecosystems, and expertise do not extend to most international markets. The recent sale of Hooq and iflix in in Southeast Asia, both of which had substantial international backing, highlights the risks of underestimating the importance of local content. Global players that do not invest adequately in building a local library will face similar challenges in many international markets.

Local players have a built-in edge in terms of both time and cost, since they can augment their libraries much faster than the global players and they are familiar with the local supply chain, which enables them to produce or source the best content at reasonable rates. Local media owners can also share content costs and supply chains with linear-TV businesses. In China, players such as iQIYI, Tencent Video, and Youku have built large market shares but have limited profitability because they must acquire all their own content, the cost of which can reach 80% of revenues. In contrast, content costs for Hunan TV-affiliated Mango TV, which shares its content supply chain with the parent TV business, are only 30% to 40% of revenues. The overall service is profitable, serving a total user base of about 100 million viewers with about 10 million paid users.

The complexity of local content production ecosystems can create an entry barrier for international attackers. Regulatory complexity, income disparity, language, and fragmentation in content ownership resulting from diverse viewer tastes all confer a natural advantage on local players familiar with the business landscape.

It should be noted that in some countries, local content can be a double-edged sword. In markets with a proven record in producing content that travels well—South Korea for the rest of Asia, for example, or Spain for much of the Spanish-speaking world—international providers are likely to bid up content costs to levels beyond the reach of local players, because they can spread the content cost across multiple markets. This dynamic creates greater urgency for local incumbents to quickly lock up international rights and establish partnerships for international distribution before the giants arrive on the scene.

Local Partnerships and Ecosystems Confer Market Clout

The success of a video service is determined by the quality of content, the ability to bundle the service to reach local consumers through various channels, and the ability to leverage stars and local opinion leaders to promote the service and market the product in locally relevant ways. A well-organized local player will almost always be more agile and adaptive than a global player, which must align the decisions of an international satellite office with headquarters in the US or elsewhere. Hotstar understood these factors well when it launched in India. By partnering with Jio (the nation’s fastest-growing telecom service), focusing heavily on local sports (cricket), and leveraging the marketing and distribution channels available to Star India, Hotstar has been able to acquire hundreds of millions of users.

The Need to Move Fast

Well-capitalized and nimble local players can combine the advantages of business model, local content, and the right partnerships into a winning hand. But they need to move quickly. The advantages will not be available forever (or even for very long), and global competition is not standing still.

Consider the example of DatViet VAC in Vietnam, the nation’s biggest privately owned media company, which stands behind a majority of the most-viewed TV shows. The network took only four months to launch VieON into the country’s streaming market, which is plagued by piracy and has no dominant players. VieON combines the might of the entire company’s content assets, talent, relationships with key opinion leaders, and marketing reach to bring everything to consumers in a hybrid advertising–subscription model. Early reception soared: in the week of its launch in June 2020, VieON was the number-one seller in both Apple and Android’s app stores and tallied a total of 1.6 million unique visitors.

Well-capitalized and nimble local players can combine the advantages of business model, local content, and the right partnerships into a winning hand. But they need to move quickly.

In contrast, in another English-speaking market, a local joint venture between two of the country’s largest content owners was established before Netflix arrived but took almost five years before it came to market. By that time, it was too late—Netflix had established a commanding position—and the local service shut down after two years, with the owners writing off hundreds of millions of dollars of investment.

As local players think through how to get to market quickly with a competitive offering, they need to address multiple issues:

- Value Proposition: What business model, pricing, package, and bundle will work in the local market?

- Content Strategy: What type(s) and genre(s) of content are missing in the market, and how much content do we need to be competitive? How much original content is required and how can we build a content pipeline quickly?

- Product Design: Is the UX/UI designed to encourage the desired user behaviors? Do we have the right feedback loops to understand how consumers are using the product? Do we have the right set of features to be competitive?

- Tech Platform: Is our service sufficiently resilient to stand the test of users in the real world? What are the platform options and the tradeoffs between in-house and third-party platforms?

- Go to Market: Who are our target customers? Which distribution channels do they have access to and which do they frequent? Could partnerships expand our reach? What is our core message? How do we manage digital marketing? How can we leverage our existing assets?

- User Life Cycle Management: What is our target user churn? Should retention strategies be active or passive?

- Talent: What type of leaders do we need for each function? Can we find talent with the needed skills for each team?

- Investment: How much investment is needed overall? By when? What is the target return on investment? Which funding options exist?

Many international markets for streaming video are still wide open. Local players that move fast and capitalize on their built-in advantages have an excellent chance to win.