The digital industrial revolution provides a golden opportunity for the continent to realize its immense potential for tech startups. Governments should take three basic steps.

Industrial revolutions, whether propelled by steam, assembly lines, or computers, have historically been slow to sweep the African continent. The era of Industry 4.0 , clean energy, and artificial intelligence promises to be different—and it has the potential to unleash a surge of innovation that could transform industries and improve well-being across the region.

That’s because unlike previous waves of industrial change, competing in the digital age doesn’t require deep scientific expertise or massive capital investment. Instead, innovators and entrepreneurs in emerging markets are in a position to tap into flows of talent and digital knowledge and convert them into novel goods, services, and business models.

Granted, Africa still has a long way to go before it can take full advantage of the digital industrial revolution. Despite impressive progress over the past decade, in virtually every metric—from internet penetration to venture capital investment to skilled workforces to “ease of doing business” rankings—the continent as a whole lags behind the rest of the world in its capacity to widely deploy cutting-edge knowledge in fields such as artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and advanced robotics.

From the ground level, however, the view in parts of Africa is encouraging. Several global growth hot spots are emerging. Morocco’s 200-company automotive cluster, for example, is launching R&D initiatives linking manufacturers to universities. Nigerian startups have attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in equity funding, and Kenya has emerged as a hotbed for fintech. South Africa’s dynamic health technology ecosystem includes more than 120 companies. Incubators, entrepreneurship training, and investment funds are making Egypt the region’s fastest-growing startup ecosystem.

The challenge is for African innovation leaders to scale up—and to spread the action beyond a handful of countries. That will require a big push from the region’s governments, working in collaboration with the private sector and academia.

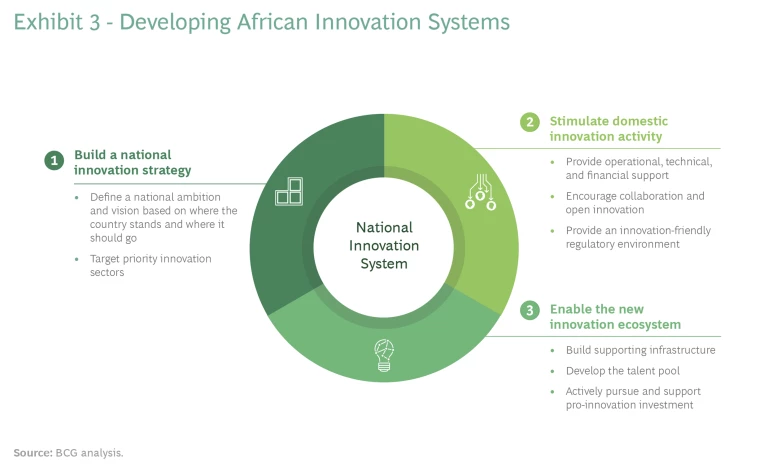

Realizing the immense potential for innovation in Africa in the digital age will require each of its 54 nations to adopt a holistic approach that fits its own circumstances and needs. Each should articulate national innovation strategies in specific sectors, enact policies that will stimulate innovation activity, and strengthen the enablers of innovation, such as digital infrastructure, skills training, investment, public-private R&D partnerships, and a robust and welcoming business environment.

Benchmarking Africa’s Innovation Capacity

As a continent, Africa has been making steady progress in its digital maturity and in improving the key drivers of technological advancement and innovation. Internet access and mobile phone usage has grown dramatically, as has science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education. From 2015 to 2020, the number of startups receiving venture capital funding in Africa soared around sevenfold. New public-private African innovation hubs anchored by some of the world’s leading technology companies are proliferating.

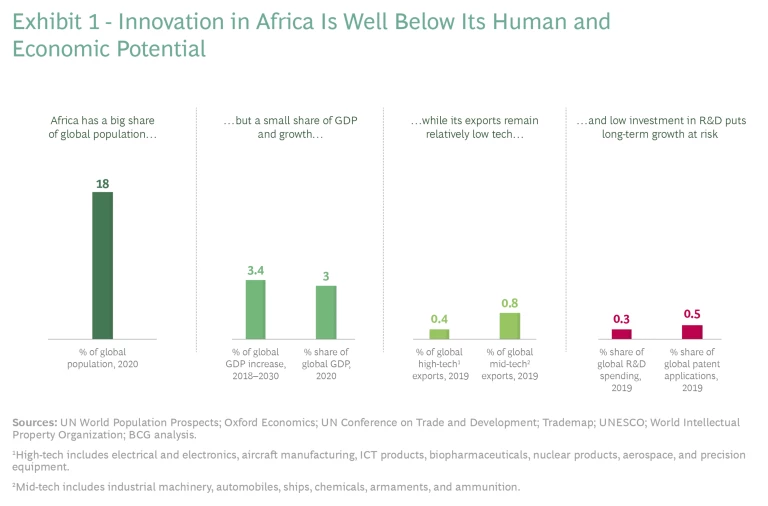

Still, the region lags in most important measures of innovation capacity. Although Africa has 18% of the world’s population, it accounts for only 0.3% of global R&D spending and 0.5% of patent applications. Trade statistics paint a picture of a relatively low-tech, low value-add region: Africa produces 0.4% of global high-technology exports and 0.8% of middle-technology exports, such as industrial machinery, autos, and chemicals. (See Exhibit 1.)

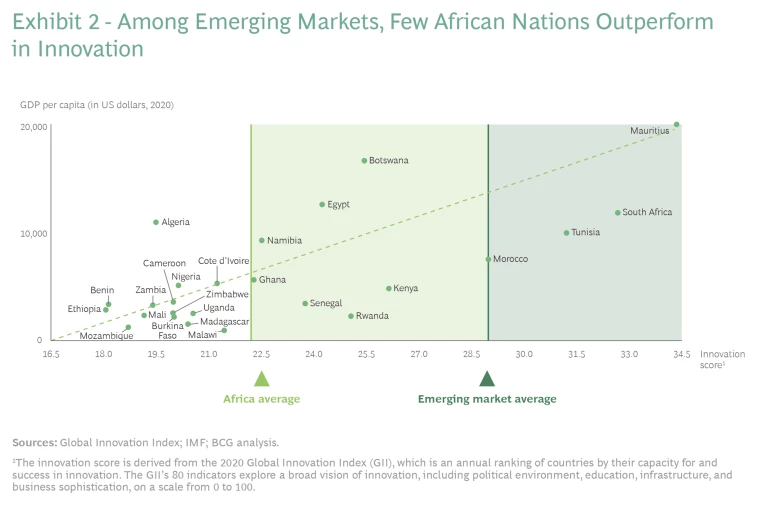

Regions with low per-capita GDPs tend to also rank low in such benchmarks as the Global Innovation

Even the progress Africa has achieved has been concentrated in a handful of nations: Egypt, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tunisia. These six countries account for half of all African mobile communication subscriptions, for example. Four nations receive around 85% of the continent’s venture capital investments and 70% of STEM graduates. South Africa, Egypt, and Morocco account for 70% of public R&D spending in Africa. By our analysis, only two nations—South Africa and Kenya—have comprehensive regulations related to innovation.

The good news is that workers in the region who are trained in the skills needed for fields like AI and advanced analytics are proving they can integrate seamlessly into global value chains. Freelance workers in such digital disciplines are in high demand, and the COVID-19 epidemic has made leading corporations far more receptive to remote work. This means that, for once, governments that invest in training can create jobs at home that will contribute to socioeconomic development and innovation in Africa—rather than a brain drain.

Given the region’s diverse markets, there is no uniform approach to building and nurturing an innovation-driven economy that will work in all of Africa. The most appropriate strategies and mixes of policies will depend on which types of innovators—such as MNCs, domestic companies, or startups—are being targeted. There are, however, three basic steps that African governments need to follow to activate their national innovation system: build a national innovation strategy, stimulate domestic innovation activity, and enable the new national innovation ecosystem. (See Exhibit 3.)

Building a National Innovation Strategy

For nations to compete and prosper in the new globalization environment characterized by rapid geopolitical, technological, and societal change, governments can no longer rely on economic development paths championed in the 20th century, such as moving up the ladder of basic industries and export manufacturing. They need to set their sights on knowledge-intensive, innovation-driven fields that can create value well into the future. Governments should begin by taking two steps:

- Define a national ambition. Governments should first define a national ambition in light of the evolving opportunities in the emerging, digitally connected, Industry 4.0-driven global economy. They should set key goals, such as new job creation , launching regional champions, boosting exports, or meeting urgent social needs. Policymakers should then thoroughly assess their nation’s existing competitive strengths and innovation capacity to deliver on the vision.

- Target priority innovation sectors. Based on this analysis, policymakers should identify industrial sectors that are in the strongest position to achieve key national goals. Egypt, for example, is seeking to leverage its deserts to build innovation hubs for renewable solar and wind energy. South Africa’s National Digital Health Strategy, launched in 2019, aims to build on its extensive health technology ecosystem to scale up innovative solutions for fighting disease and improving the quality of care. Similarly, Morocco is leveraging its large and growing automotive manufacturing cluster to encourage innovation. The cluster began in 2007, when Renault announced it would build an eco-friendly production site in Tangier, with the Moroccan government contributing land, a training center, and various financial incentives. It has now grown to include several other OEMs, including Groupe PSA and an announced electric vehicle plant by China’s BYD, as well as numerous Tier 1 and Tier 2 suppliers that multiply the job creation effect. Now Tangier is becoming a growing regional base for automotive engineering and R&D.

For nations to compete and prosper in the new globalization environment, they need to set their sights on knowledge-intensive, innovation-driven fields that can create value well into the future.

Stimulating Domestic Innovation Activity

Nations that have successfully launched new innovation clusters have used a number of tools to stimulate innovation activity and attract foreign partners. African governments should consider the following measures:

- Provide operational, technical, and financial support. Nations such as Singapore and Israel provide a wide range of support for R&D and entrepreneurship in key sectors, such as research facilities, open access to data, e-commerce competence centers, and financial assistance such as tax incentives and grants. To develop Be’er Sheva into a cybersecurity capital, for example, Israel relocated more than 10,000 intelligence personnel to the city, established a national R&D center, and supported undergraduate and graduate programs at polytechnic institutes and universities to train thousands of cybersecurity experts. In terms of financial incentives, Morocco gives five-year exemptions on corporate taxes for companies that set up operations in the global logistics gateway Tanger Med’s special economic zone, which contributes to local technology transfer. Kenya waives value-added taxes and gives preferential corporate tax rates to companies that engage in technological research and business incubation. It also promotes innovation-oriented procurement, such as setting aside a portion of state contracts for e-commerce purchases from micro, small, and midsize enterprises and local startups.

- Encourage collaboration and invite open innovation. Policymakers should develop platforms that enable both large and small enterprises within their ecosystems to collaborate and widely disseminate new technology. Singapore, for example, promotes open innovation through dedicated infrastructure at its JTC LaunchPad for nurturing startups, the Enterprise Singapore program for small and midsize enterprises, and the Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (A*STAR), which helps companies adopt the latest technologies.

Public-private partnerships with MNCs at the technological forefront of their fields can be particularly valuable in strengthening national innovation systems and enhancing connections with global ecosystems of partners. Morocco’s automotive cluster offers several good examples. In 2018, Renault established an R&D partnership with the Mohammadia School of Engineers in the automotive, energy, and environmental fields that included an academic chair and degree programs for hundreds of students. Groupe PSA, whose brands include Peugeot, Citroën, DS Automobiles, Opel, and Vauxhall, also opened a technical and R&D center in Tangier that employs more than 500 engineers and technicians and that has built relationships with nine Moroccan universities. A number of global technology giants also have been helping to develop innovation hubs in several African countries, including Rwanda, Ghana, and Nigeria.

Governments can also help local innovators by opening their markets to greater competition. And they should push local champions, such as powerful state enterprises or private monopolies, to develop their own innovation ecosystems for startups.

- Provide an innovation-friendly regulatory environment. A supportive and agile regulatory environment, with strong protections for intellectual property, is especially critical given a business landscape in which innovators increasingly collaborate within digital ecosystems and flexible networks of partners—and must move fast to capture opportunities. South Africa’s approach to regulation has been key to its success in health technology and fintech. For example, the government has established innovation “sandboxes” that enable fintech startups to test new business models, strengthen intellectual property rights, and accelerate procedures for registering and incorporating new companies and approving mergers. Nigeria has also introduced a fintech innovation sandbox to lower barriers to entry for new players. Meanwhile, help from the Kenyan government in establishing a strong relationship between Safaricom and the country’s central bank was crucial to getting the licensing approval and deposit insurance required for digital banking service M-Pesa to be successful. A good start for any government is to establish public-private working groups to shape better regulation that attracts the specific desired investment, thereby increasing private sector confidence and coordination.

Enabling the New Innovation Ecosystem

A well-designed policy framework can lay the ground for a thriving innovation economy. But governments—especially in developing economies such as those in Africa—must also play a lead role in driving the investments that are needed to build innovation capacity. Governments can leverage the success of leading-edge companies to support the development of innovation ecosystems by collaborating with the private sector in the following areas:

- Build supporting infrastructure. In addition to physical digital infrastructure, such as fiber-optic cables and 5G wireless broadband networks, governments can facilitate innovation ecosystems by investing in innovation hubs, R&D facilities, and small-business incubators. Nigeria has established more than 80 innovation hubs in key cities that have attracted venture capital and foreign investment and support for small companies and entrepreneurs. For instance, the Eko Innovation Centre in Lagos, a public-private partnership, is emerging as an important catalyst for innovators seeking to develop new solutions and business models to address African poverty. SmartXchange, a public-private incubator in South Africa, connects startups and small and midsize enterprises in the media, information technology, and electronics sectors with foreign research institutes, companies, and investors.

- Develop the talent pool. Currently, there is a mismatch in most countries—and particularly in Africa— between the needs of innovation-driven companies and the available skilled domestic workers. Africa’s governments and private sector can help fill these gaps by expanding STEM education, skills enhancement, and entrepreneurial training.

IBM Digital and the United Nations Development Programme, for example, have launched a free initiative that hopes to train 25 million African youths over five years in digital, cloud, and IT skills. South Africa has established mLab, a youth-focused, technology-enabled skills development program to promote startups, and has launched a training initiative for digital health workers. In Egypt, which has the fastest-growing startup ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa region, entrepreneurship training is now a requirement in several public universities.

It’s key that governments adopt a holistic strategy that ensures coordination of skills programs with initiatives for attracting investment so that training opportunities are tailored to jobs being created. If the focus is digital media, for example, visual effect and animation modules might be required in some local STEM-related degrees. If e-commerce is targeted, broad digital literacy and customer service programs could be offered. To promote startup entrepreneurship, governments should ensure that there is a vibrant, international standard living environment that will attract and retain global talent.

- Actively pursue and support pro-innovation investment. Because private early-stage venture and research funding tends to concentrate in a few hot spots, most African governments need to play an active role in stimulating investment in innovation activity. A government body should be empowered to help coordinate foreign direct investment and grants for research institutions and serve as a foundational investor with venture capital funds in startups.

While there is no single strategy that can work across such a diverse region as Africa, the basic approach of defining national strategies, stimulating innovation activity, and enabling the new innovation system applies.

Mobile money took off in Kenya, for example, after the partially state-owned telecom company Safaricom launched M-Pesa in 2007. Safaricom had raised funds from a UK Department for International Development program that supports public-private partnerships devoted to improving access to financial services. Among Egypt’s pro-innovation investment initiatives were the establishment of the $57 million Fintech Fund and the creation of a company with $30 million in capital to make direct and indirect investments in startups and small enterprises.

While there is no single strategy that can work across such a diverse region as Africa, the basic approach of defining national strategies, stimulating innovation activity, and enabling the new innovation system applies. Success will require collaboration among all actors in the innovation ecosystem: MNCs, academic institutions, investors, and local companies of all sizes, from small enterprises to national champions in the private and public sectors. The specific policy formula should vary according to each country’s level of economic maturity, existing innovation capacity, competitive strengths, market ambitions, investor demands, and national needs. Also, the policymaking and regulatory processes must remain agile enough to enable swift adjustment to technological change and the shifting dynamics of the global economy. As African nations continue to aggressively invest in their innovation capacity—and implement the right blend of strategies and policies—we believe the continent is poised to write a new chapter in its economic history. But Africa should move now, while there is still ample opportunity to get in on the ground floor with innovation cycles that are redefining the future.

The authors wish to thank Emna Bellagha and Reshma Jayaprabha for their contributions to this article.