All organizations, regardless of their purpose or mission, wrestle with adapting to rapidly evolving digital technologies. For higher-education institutions, these technology challenges are further complicated by a perfect storm of a pandemic and disruptive long-term trends—declining enrollment, rising operating costs, and changing expectations of the learning experience. These trends raise the ante on replacing legacy IT infrastructure and applications with technology that better equips higher education for a digital world.

Our research on successful digital transformations among enterprises in many industries—a process that we call reaching digital maturity —points to three areas of technology improvement that drive large-scale institutional innovation: using cloud infrastructure; expanding access to data; and developing digital tools to improve business processes through advanced analytics, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI).

BCG’s fourth annual Digital Acceleration Index , published in 2020, showed that the most digitally mature companies outperformed their peers in revenue growth, time to market, cost efficiency, product quality, customer satisfaction, and total shareholder return. Higher-education institutions that follow their own path to digital maturity through investments in the cloud, data, and analytics can achieve better results in the areas that matter most to educators: student success in enrollment, retention, and employment; operational efficiency; innovation in research; and innovation in learning.

In February and March 2021, BCG partnered with Google to survey and interview US higher-education leaders to find out their views on the state of digital maturity in the higher-education sector. The survey found strong agreement among institutional and technology leaders that moving on-premises IT systems to the cloud, centralizing and integrating data, and increasing the use of advanced analytics are high priorities.

At the same time, though, we found a big gap between respondents’ perceptions of their institutions’ digital maturity and the reality. Overall, more than 55% of university leaders considered their schools to be “digital performers” or “digital leaders” as we defined those terms in the survey. (See “Higher-Education Leaders’ Perspectives and Priorities on Digital Transformation.”) However, only a third of tech leaders at these universities expressed at least moderate confidence that their data was sufficiently integrated and usable to support making key business decisions and improving student outcomes. Furthermore, only a quarter said that their institutions regularly used data analytics.

Higher-Education Leaders’ Perspectives and Priorities on Digital Transformation

The survey defined technology as any IT systems, software applications, and tech hardware (such as servers and classroom tech). We asked various questions about how institutions are currently using technology and how they are approaching improvements to technology. Typical technology improvements in higher education include moving on-premises infrastructure to the cloud, consolidating and improving access to data, expanding computing power, and using machine learning/AI to improve business processes.

We also asked respondents to select one description that best represents how they view their institution’s digital maturity, using the following taxonomy:

- Digital Starter. Institution leaders (for example, a provost or dean) will sometimes work on ad hoc digital innovation initiatives with IT leaders for example, a CTO or CIO), but the collaboration does not include a target state for digital innovation at the institution.

- Digitally Literate. The institution recognizes the need for digital innovation and defines a roadmap, but schools, departments, or functions execute digital initiatives in silos.

- Digital Performer. The institution as a whole and IT leaders are building capabilities to manage digital innovation in an integrative way across departments.

- Digital Leader. Digital innovation is in place throughout the institution, and leaders see it as a key value driver. The institution outperforms its peers on key digital metrics.

What’s holding higher education back? Certainly, it is not the technology. But in our work with corporations and governments, we regularly encounter various organizational barriers to change—and especially to initiatives designed to achieve large-scale, step-change goals. Organizational challenges in higher education are similar: competing priorities, decentralized decision making, budget constraints, cultural resistance to change, and gaps in tech staff’s skill sets, to name a few. Still, leaders understand that the way to win daily battles and overcome institutional inertia is with a strong vision of what’s best for the institution as a whole, tied to specific goals. Although only a handful of schools have reached digital maturity, as we define it, others can learn a great deal from their example.

Digital Maturity Improves Outcomes in Higher Education

Digital maturity is an existential issue for higher education—and not just because technology is changing expectations about the learning experience. Certainly the pandemic has lit a fire under demand for virtual learning and a more personalized form of education delivery, but digital capabilities also hold the key to dealing effectively with declining enrollment and rising costs.

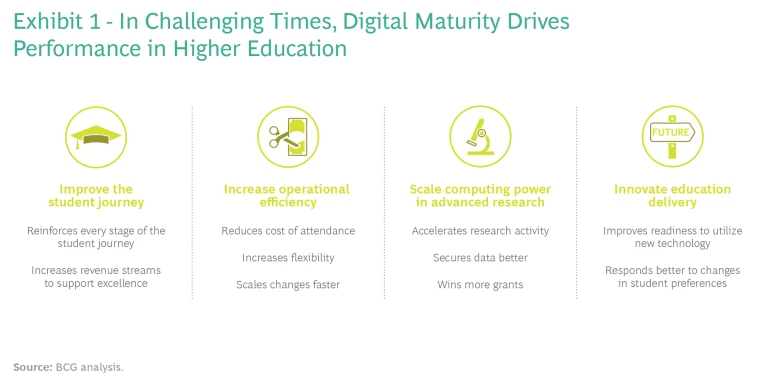

Leaders in higher education have identified four goals that are immutable and under pressure. (See Exhibit 1.) Strategic technology plans to use the cloud, data, and analytics are critical to improve performance in each area.

Improve the student journey. National education statistics show that enrollment in US higher-education institutions has been declining for ten consecutive years. In 2020, total enrollment fell by 2.5% from the previous year’s figure. Forecasters predict a further decline in 2021, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. Meanwhile, efforts to tie public funding to student outcomes are increasing.

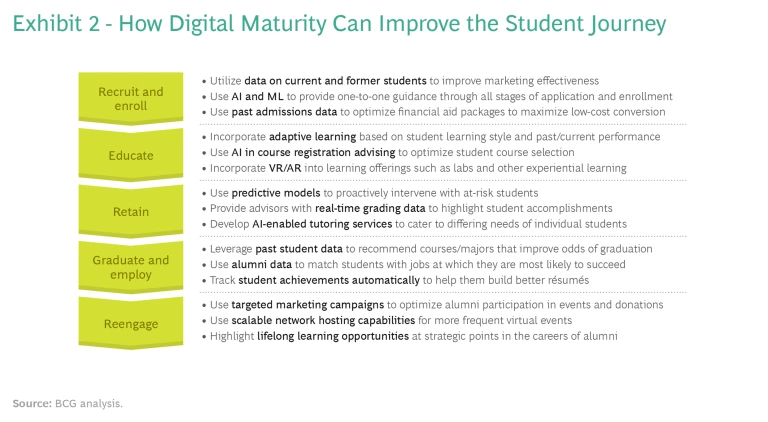

To sustain academic excellence and keep schools financially viable, higher-education institutions must use all available digital tools to improve the student journey. Nearly half of survey participants identified improving student outcomes as the number one factor driving their technology investments in such areas as stronger recruiting and retention of students, improved digital education delivery, increased government funding, and sustained donations from alumni. For example, Georgia State University built a predictive analytics model that incorporates 800 indicators and serves as an early-warning system to help faculty advisors intervene with at-risk students. In the four years after the program began in 2012, the university’s graduation rate rose by 7 percentage points, and the average time to graduate decreased by more than half a semester. Digital solutions can improve the student journey in many other ways as well. (See Exhibit 2.)

Increase operational efficiency. According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, core non-administrative expenses at public and private not-for-profit higher-education institutions in the US increased by 18% (inflation adjusted) from 2010 to 2018.

Shifting IT systems and applications to the cloud, if done correctly, can lower total cost of ownership (by eliminating the need to maintain legacy IT infrastructure on campus) and enhance operational agility (by tapping into the cloud’s flexibility to scale up and scale down as needed). Survey participants told us that they plan to increase their use of the cloud by more than 50% over the next three years.

Scale computing power in advanced research. Increasingly complex advanced research agendas require more scalable computing power and more secure, long-term data storage. Roughly 67% of researchers polled in December 2020 by EDUCASE Research News said that they anticipated focusing on access to networked, remote, or cloud-based research tools or services in 2021. This is already occurring at cutting-edge research universities such as Harvard Medical School. A research team there used cloud computing early in the pandemic to scale up screening of ultra-large digital libraries of chemical compounds to speed up COVID-19 drug discovery research, including tests of a billion compounds in five days.

Innovate education delivery. Today’s digital-native undergraduate and graduate students are driving the evolving delivery of education. Increasingly, students consider the quality of the digital experience, not just the college experience, in choosing an institution. According to a Google consumer survey presented at the 2020 Arizona State University + Global Silicon Valley Summit, 55% of 18- to 24-year-old students expect hybrid learning modalities to continue in the post-COVID-19 period. In addition, many adult learners are looking for more options that accommodate their work and family needs. Digital maturity will enable institutions to become more agile and efficient in delivering education that keeps pace with changing societal norms, responds to shifting student preferences, and anticipates future disruptions such as another pandemic.

Reducing the Gap Between Perception and Reality

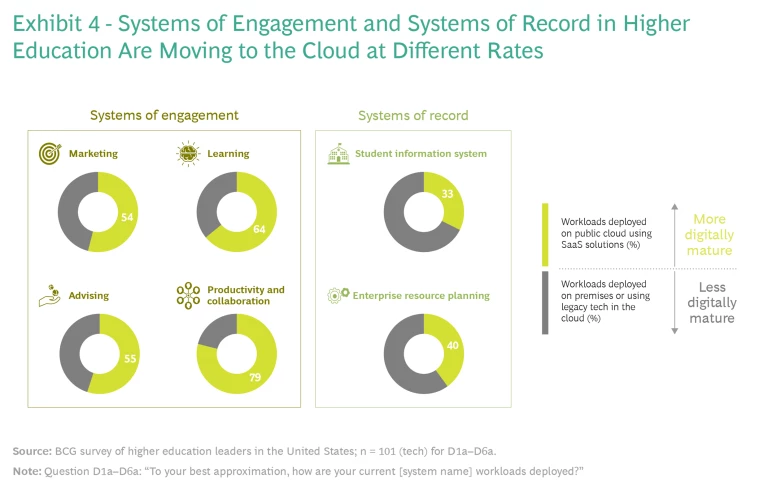

The first step toward achieving digital maturity is to understand where higher education lags. Although tech leaders in higher education say that their institutions have shifted nearly half of their IT systems to the public cloud, nearly two-thirds of them have low confidence in the accessibility and usability of data to improve business processes. Typically, the cloud is better than on-premises solutions as a platform for centralizing data—especially if it uses cloud-native software-as-a-service (SaaS) solutions. But most tech leaders still lack confidence in their data because of the sequence in which systems move to the cloud.

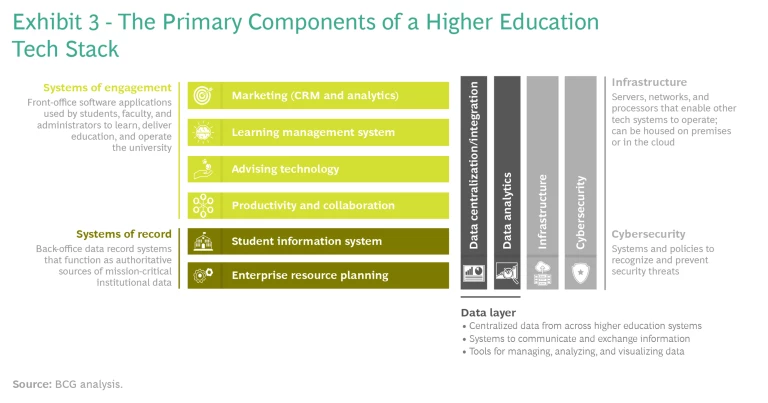

A typical higher-education tech stack has several components. (See Exhibit 3.)

The ability to use data residing in systems of engagement (marketing, learning, advising, productivity, and collaboration) and in systems of record (student information systems and enterprise resource planning systems) is critical to discovering and unlocking opportunities to improve student outcomes and operations. In a digitally mature organization, systems of engagement and systems of record are optimized to work together. However, our survey showed that universities are shifting their systems of engagement to the cloud faster than their systems of record. (See Exhibit 4.) This is partly because systems of engagement tend to be easier to move to the cloud through the use of SaaS solutions.

The mix of legacy and cloud-based systems and the pace at which specific systems migrate to the cloud can significantly affect the effectiveness of digital capabilities because many legacy systems are not designed to operate in a cloud environment. For example, most on-premises legacy systems—especially student information systems—do not readily support efforts to cross-fertilize data or to use advanced digital tools such as predictive analytics, machine learning, and AI models.

Beyond streamlining data integration, cloud-based SaaS solutions that are optimized to work in the cloud can increase scalability and flexibility and lower the total cost of ownership of IT systems. Institutions that merely “lift and shift” legacy systems to the cloud may find it harder to achieve measurable improvements in data integration and cost reduction.

Still, there is nothing wrong with incremental changes and improvements. Centralizing data and transitioning to the cloud do not need to occur all at once. Leaders should base their decisions about which systems to move, when, and how on desired performance outcomes. For instance, a university looking to improve recruitment from prospect to applicant might choose to focus first on transitioning from an on-premises CRM system to a cloud-based CRM SaaS solution. Insight at this level can make spending on recruitment much more efficient. Alternatively, a college interested in improving retention might start by migrating from a legacy student information system to a cloud-native equivalent. The college could then leverage data on current and former students to become more proactive in intervening with at-risk students (as Georgia State University did).

Digital Transformation Should Be a President’s Top Priority

The journey toward full digital maturity is long, but leaders who articulate a strong vision and commitment can make it happen more quickly and successfully. To ensure that the vision delivers a strong return on investment (ROI), leaders should tie it to specific needs (more effective recruiting) and outcomes (better retention). Digital transformations are a university-wide journey, but small pilot projects are a good way to start. Thinking big but starting small can reduce resistance to change, build positive momentum, and lead to better results.

Our research highlighted a number of common organizational roadblocks found in higher education—and ways to handle them:

- Prioritizing the Urgent over the Important. Organizations tend to fix urgent problems but defer critical investments in foundational capabilities that take time to show results. Almost 40% of survey respondents said that competing priorities impeded their ability to achieve the technology improvements they desired. To overcome this problem, the provost of a state-wide community college system created a prioritized plan for digital investments and brought the right people to the table. The college system’s CIO became a co-owner of student success goals and attended senior administrative leadership meetings. In this way, leaders were able to incorporate the strategic objectives of different departments into a continually updated digital roadmap.

- Decentralized Decision Making. Survey respondents report that, on average, 8 to 12 university leaders are involved in making technology-related decisions. Individual colleges, institutes, and departments generally control their own technology decisions and budgets. Decentralized decision making can delay large university projects, and it can create a patchwork of systems that are difficult to integrate. In the 1990s, a large multicampus university used the phrase “one university, many places” to communicate its intention to centralize and integrate data. Today more than half of the university’s IT services are centralized, and clear governance rules prescribe which decisions should occur at the university and department levels. This is important as a way to balance the scale and speed of coordinated decision making while preserving autonomy and a sense of local ownership.

- All-Too-Human Resistance to Change. Technology can be easier to change than behavior. Indeed, our survey respondents listed internal resistance to change as a major barrier to implementing technology improvements. Yet some universities have overcome this problem. Research faculty at one university used grant money to buy and store servers across campus, without the IT function’s involvement. To resolve this inefficiency and save money, the CIO suggested moving research computing to the cloud. Initially the research team resisted this option. So the CIO identified a well-funded, high-profile faculty member who was willing to shift computing to the cloud and help persuade his colleagues that the cloud-based approach to computing and storage was better for researchers and for the university. Successful institutions encourage staff in multiple roles to advocate for the vision of digital maturity. Small pilot projects add visibility to objectives and offer proof of concept when the results are good.

- Internal Gaps in Digital Tech Talent. Schools need to be resourceful to retrain and improve their current employees’ digital skill sets. More than two-thirds of tech leaders said they would need external help to implement large-scale technology improvements if undertaken today. Outsourcing is one solution to bridge an internal skills gap, but other solutions are possible. For example, the CIO of a state research university identified students who had the requisite skills to build needed cloud-based data analytics tools. Another university enticed recent graduates to work at the university for a few years to gain cloud experience and certifications.

- Too Narrow a View of Institutional Value and ROl. In our survey, 44% of respondents cited implementation cost as a key barrier to investing in technology improvements. In many instances, however, the underlying problem is that the institution has not fully calculated a business case and ROI for the investment. Business cases for foundational digital capabilities must take into account measures that develop slowly or are hard to quantify. Examples include faculty time and money saved through automation and more efficient operations, and better enrollment, retention, and on-time graduation numbers resulting from improvements in the student experience.

In a world where higher education faces many new challenges and competing priorities, the importance of building up an institution’s digital capabilities can get lost. Although 70% of higher-education leaders in our survey considered digital capabilities to be a high priority for their institution, only 15% identified it as one of their highest priorities.

Yet the value of moving IT systems to the cloud, improving access to data, and using that data to improve processes is becoming increasingly clear. The institutions we see leading the charge showcase some of the many opportunities that cloud-based digital transformations offer for improving student outcomes, operations, and research.

As we have noted, higher education is digitally far behind most other industries. One reason is that schools struggling with immediate concerns don’t have the capital or the talent to make large investments in their IT systems—and their digital future. The other is that education is a relatively small segment of the IT market compared with financial services and health, so it is a lower priority for the bigger technology vendors and attracts less investment.

Digital transformation isn't just about having the latest technology. Changing the learning and business models in higher education during this tech modernization cycle is a matter of survival for some and a competitive necessity for all. The rush to remote learning because of the pandemic has elevated digital investment on strategic agendas, but too many schools are still moving too slowly, at their peril. Now is the time for the people who lead their institution’s digital journey to be bolder or be disrupted.

We would like to thank the following key contributors and supporters of this article: Melanie Gaynes, Kevin Rodriguez, Meghan McQuiggan, Allison Bailey, Renee Laverdiere, and our knowledge team.