By acting now and working together, we can develop the solutions to avoid a climate disaster and make sure everyone has access to clean, affordable, and reliable energy. — Bill Gates

Climate Solution Innovation

Global momentum is building to achieve net zero in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—and to do so more quickly than previously envisioned. Getting there will require unprecedented levels of innovation. While a fast-rising number of companies and governments are committing themselves to ambitious net-zero goals, most focus the strategy exclusively on emissions and expect the necessary technologies and solutions to become available as needed.

Annual global emissions of carbon dioxide equivalents now amount to about 51 gigatons. Some estimates, such as the P4 pathway defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), show that today’s technologies have the potential to reduce global emissions by about two-thirds. More innovation-driven projections—such as IPCC’s low-energy demand pathway, P1—do not bank on any new technologies but instead assume radical business model and policy innovation. It is clear that reaching climate change goals requires new technologies and novel business models and markets. Fortunately, there’s momentum building for a new generation of innovative solutions.

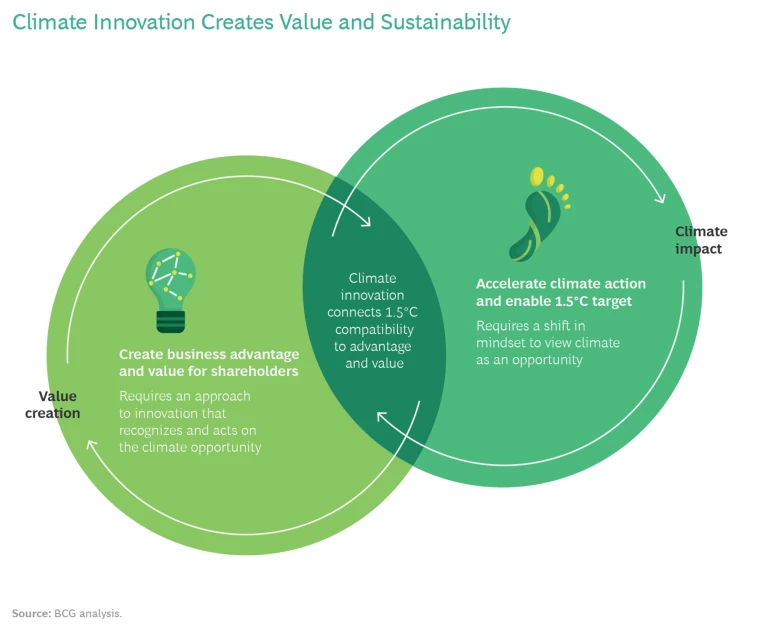

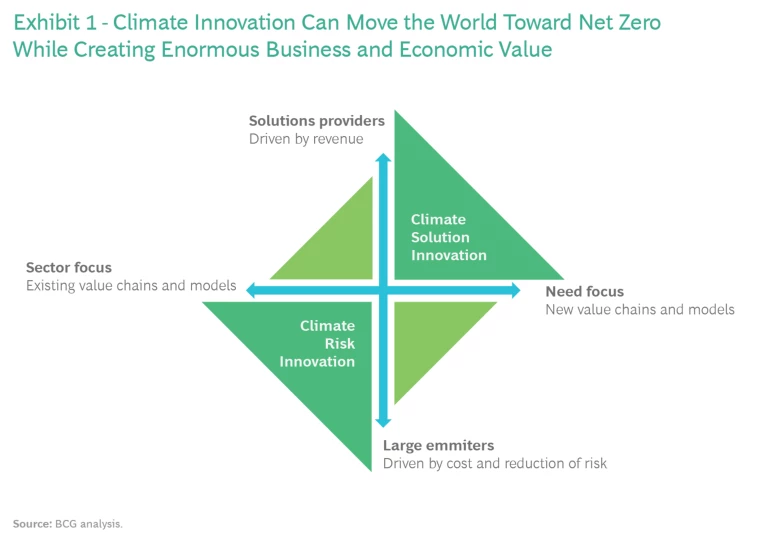

A big reason for optimism is that within the solutions lie major opportunities for businesses, investors, and governments. They should start with a shift in mindset—looking at companies as providers of solutions rather than only sources of emissions, focusing on new sources of revenue over rising costs, and seeking transformative models rather than incremental improvements. Companies can create business advantage and value while accelerating climate action and helping to meet the 1.5°C target envisioned in the Paris Agreement. Governments can boost economic growth with support for what we call climate solution innovation. (See Exhibit 1.)

Major companies are already on the move. General Motors, among others, has said that it wants to end the production of gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles by 2035. In February, the chairman of Fortescue Metals Group told the Financial Times, “In 15 years’ time, the world energy scene will look nothing like what it does now. Any country which does not take green energy very seriously, but clings to polluting energy, will eventually get left behind.”

Here’s how we can have our climate cake and eat it, too.

The First Wave of Climate Champions Shows the Way

Seismic shifts are beginning to occur in government policies and public- and private-sector initiatives. Consider a few examples.

In September 2020, the president of China committed the country to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060—an enormous challenge for the world’s biggest annual carbon emitter—but a recent BCG analysis found that China has economically attractive and socially viable pathways to achieve its decarbonization goals. The total cost will be substantial—about $13.5 trillion to $15 trillion through 2050, but the investments will have a material benefit for GDP, contributing 2% to 3% during the first half of the century. Green technology investments alone will account for more than 2% of China’s GDP by 2050. Far from hindering economic growth, decarbonization could in fact stimulate the economy.

As part of South Korea’s Green Growth strategy, the government provided early support for battery storage projects. Investment in R&D enabled breakthroughs in stable multicycle charging and support for early integrated battery deployment. Lithium-ion battery costs declined nearly 90% from 2010 to 2019, and South Korean battery producers captured a leading market share by 2013.

Combating climate change has entered the mainstream, and corporate and venture capital investment in climate technologies is on the rise. In 2020, US investors doubled the money they put into exchange-traded funds focused on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria—rising to $25 billion. Industry groups, such as the influential Business Roundtable in the US, are emphasizing the need to embrace sustainable practices and lead the way through investment and innovation. A January 2020 Bloomberg News article spotlighted ten multibillionaires around the world whose fortunes come substantially from early forms of climate innovation.

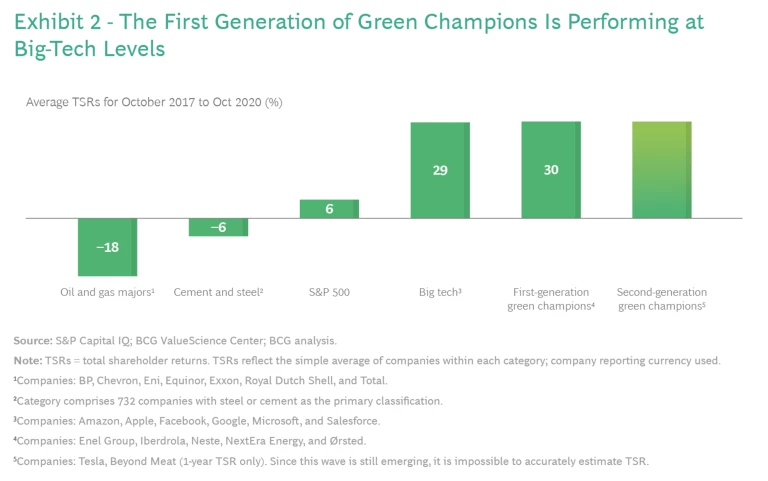

The most exciting action is taking place at the leading edge. The first generation of “green champion” companies is generating shareholder returns at levels similar to those of such high-flying tech firms as Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google. From October 2017 to October 2020, some companies—including Enel Group, Iberdrola, Neste, NextEra Energy, and Ørsted—generated annual total shareholder returns on the order of 30%. The returns for an emerging wave of second-generation green champs, including Beyond Meat and Tesla, ranged from almost 70% to 80%. (See Exhibit 2.) The value of Tesla alone far outstrips that of any other car maker.

These and other forward-looking companies are demonstrating that climate solution innovation is all about creating value. They are showing how to create new revenue streams by entering new markets or developing offerings that cater to high-priority economic and social needs. They are winning new customers and strengthening their brands through positive environmental and social contribution. Early movers are using scale and market position to create network effects and lower costs. Innovators are building more resilient business models through reinvention in the most critical parts of the value chain, reducing exposure to increasing costs and regulatory constraints.

The Climate Solution Innovation Canvas

While breakthroughs in technology are critical to generate new opportunities, not all companies need to play in the breakthrough tech fields.

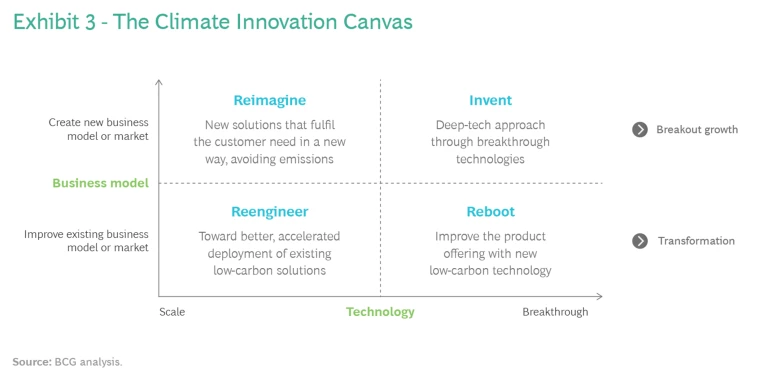

Companies can choose from various approaches to climate solution innovation, but they are well advised not to limit their ambitions to one or two options. They can both improve existing models and markets and create brand new ones. Equally, they can scale up existing technological solutions and support the development of more disruptive ones. (See Exhibit 3.) In all instances, though, companies need to move away from looking at themselves only as sources of emissions and see themselves as potential providers of solutions for a fundamental societal need. It’s also important to recognize that they don’t necessarily need new technology to innovate. While breakthroughs in technology are critical to generate new opportunities, both in terms of value creation and climate impact, not all companies need to play in the breakthrough tech fields. There remains huge potential in deploying and scaling up existing technologies through business model innovation and, especially, digitization.

Below we explore the opportunities in each area and examine what leading companies are already doing.

Reengineer. Climate change is quickly altering the context for most businesses. Those that can successfully innovate will outperform others and secure long-term value by moving quickly toward better, accelerated deployment of existing low-carbon solutions. Customers and investors are embracing companies that demonstrate viable solutions.

Consider the example of Neste, which has leveraged technology able to transform fats into molecules that can replace fossil fuels to help customers reduce GHG emissions. Neste has developed renewable fuels for road, air, and marine transport as well as for chemicals (including base oils and plastics).

Originally the state oil company of Finland (the Finnish government continues to own about 35%), Neste envisioned becoming the world’s leading producer of renewable diesel in the early 2000s and has transformed its business to make the transition from oil and gas to renewable fuels. Neste began production of 100% renewable diesel in 2010 and has since expanded to three global production facilities. It owns 1,000 gas stations in four countries, including Finland’s first low-emission service stations, which feature renewable diesel and electric-vehicle charging. It also offers GHG emission-reduction services to customers through Neste Engineering Solutions. In 2019, Neste helped customers reduce GHG emissions by 9.6 million tons, the equivalent of removing 3.5 million passenger cars from the roads for a full year. Neste’s ambition for a second wave of growth is to become a global leader in renewable and circular solutions.

Neste generated overall revenue growth of 6% to €15.8 billion in 2019 with renewables revenue rising 24%. With more than 25% of its revenue considered “clean,” the company has earned high ESG ratings from investors and others.

In a completely different industry, Norwegian crop nutrition company Yara is using satellite technology to help farmers around the world optimize yield and quality while minimizing waste and cost. Established in 1905 as the world’s first producer of mineral nitrogen fertilizers to solve the emerging famine in Europe, Yara today offers crop nutrition products, solutions, and knowledge. According to Svein Tore Holsether, the company’s president and CEO, “Yara’s business model is centered around building a profitable business by solving societal challenges. Over the past decades, Yara has moved from an owner of assets and producer of fertilizer to becoming a complete solutions provider, both for farmers and food companies. We are transitioning from growing volume to growing value. This is a decisive, conscious, and forward-looking development, allowing for improved value creation and answering to stricter regulations and a rightfully stronger public engagement.”

Yara’s portfolio of digital farming solutions enables farmers to maximize the yield and quality of their harvests while reducing environmental impact. For example, professional market solutions, such as Atfarm, allow farmers to monitor crop growth through satellite images, receive fertilization recommendations tailored to their fields, and make in-season adjustments throughout the year. N-Tester is a handheld precision farming tool that allows farmers to measure crop nitrogen requirements in real time. The Yara Water Solution uses crop-sensing technology to increase nutrient and water use efficiency. Yara also has an entire suite of solutions for small farmers that includes a weather forecast app and a networking app that connects farmers to peers and experts.

From a business point of view, Yara’s investment in digital solutions is helping farmers find ways to monetize over a century’s worth of agronomic knowledge. Yara focuses on developing scalable and accessible solutions to meet the needs of more than 500 million small farmers and robust platform solutions to meet the needs of large enterprise farmers.

A few lessons on climate-inspired business reengineering can be drawn from Neste and Yara. First, climate action should be firmly embedded in a company’s strategy, purpose, and culture. This goes beyond simply signing a pledge. It means having a plan, making climate action part of the business, and regularly reviewing progress against KPIs, just as is done in every function and business unit.

Climate action should be firmly embedded in a company’s strategy, purpose, and culture.

Second, companies can use the transformation to shift perceptions of their external valuations. Management needs to develop a new shareholder value story with clear articulation about the potential for long-term value in low-carbon businesses.

Finally, companies need the right capabilities to succeed, including innovation-oriented talent and an open approach to partnerships and coalitions.

Reboot. Often, existing constraints thwart new technologies from reaching their full potential. An additional innovative solution is required to break through barriers or present a new way of solving a problem. Major technologies for combating climate change, such as battery power and wind-generated electric power, have established their viability in the marketplace but need a technological assist to move to the next level of impact.

Major technologies for combating climate change have established their viability in the marketplace but need a technological assist to move to the next level of impact.

In 2011, two former Tesla employees and a professor at Georgia Tech, in Atlanta, recognized that materials developed using nanotechnologies could dramatically increase the energy density of rechargeable lithium-ion batteries and enable smaller, lighter, longer-lasting electronic devices. This advance promised to have a major impact on the range of electric vehicles (EVs) and boost mass adoption of affordable, long-range battery-powered cars. The resulting company, Sila Nanotechologies, has developed a silicon-based anode that replaces graphite in lithium-ion batteries. The new anode improves the energy density of batteries by 20%, meaning that 20% fewer cells are needed in each battery pack, and the battery costs 20% less.

Sila products can be dropped into existing commercial-battery-manufacturing processes. Manufacturing partners can produce higher-performing cells in their existing factories on current production equipment; they do not need to retool. The improved battery technology can be applied to a variety of other applications besides EVs, including consumer electronics, electric power storage and transmission, and electrified flight, all of which have the potential to accelerate the world’s transition to renewable energy. On the basis of its latest round of funding, Sila is now valued at $3.3 billion. The company has partnered with BMW, and Daimler is both a partner and investor.

A big constraint on wind-generated power is the construction of wind farms in locations with a steady airstream and a limited number of neighbors. Offshore locations are an attractive solution, but constructing windmills in deep-water settings, where winds blow strongly and more steadily, has been prohibitively expensive—until recently. Enter Equinor, with new technology that enables offshore wind turbines to float, obviating fixed moorings. Motion controllers and sensors regulate the turbine blades in relation to wind speed, intensity, and direction to prevent capsizing. Equinor’s Hywind Scotland, the world’s first floating wind farm, powers some 20,000 British homes. The company’s upcoming 88-megawatt Hywind Tampen floating wind farm will power five oil and gas installations in the North Sea with renewable power. Floating wind farms could power up to 12 million homes in Europe by 2030.

In both of these cases—as in others, such as Form Energy, which has developed long-duration energy storage technology that could be a major missing piece in the clean-energy puzzle—the key to the breakthrough was recognizing a bottleneck or significant constraint to emerging technologies and innovating a technology to remove or get around the barrier.

Reimagine. Satisfying changing customer demands, particularly those rooted in evolving views of climate change, may require reimagining business models and services. Consider mobility, for example. Before the pandemic hit, many consumers were already rethinking the concept of single-car ownership and embracing alternatives, such as renting and ridesharing, as they looked toward a future of autonomous vehicles and robotaxis. Tech giants, including Apple and Google, have been piloting autonomous driving, and major auto OEMs, including GM and Volkswagen, have been exploring autonomous-vehicle manufacturing and mobility models. Upstarts turned unicorns—such as BlaBlaCar, Grab, Lyft, and Uber—were early mobility movers.

Another unicorn, DiDi Chuxing, has pioneered mobility as a service in China. Founded in 2012 as a taxi-hailing service, DiDi rapidly expanded its portfolio of offerings to encompass artificial intelligence (AI), big data, smart city transportation and self-driving technology. It serves more than 550 million users in Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Russia, and provides more than 10 billion passenger trips a year. Daily trip volume for DiDi’s core mobility services exceeded 60 million during the first week of October 2020. Its multimodal mobility-as-a-service platform attracts more active users, who then drive higher utilization rates—which, in turn, attracts more active drivers and vehicles through improved profitability. Ultimately, riders experience a better user experience via reduced wait times and costs.

DiDi offers a full range of app-based transportation and local services including taxi hailing, private-car hailing, peer-to-peer ridesharing, buses, bikes, e-bikes, designated driving, automobile solutions, delivery and logistics, and financial services. Its ecosystem-based approach accelerates adoption (the DiDi miniprogram is available on the WeChat platform, for example) and boosts innovation. The company is laying the foundation for the spread of autonomous and connected EVs as well as smart cities. In 2019, nearly 1 million electric cars operated on DiDi China’s platform, accounting for one-fifth of all EV mileage in China. This translates into a reduction of 0.59 million tons of CO2 emission every year. From 2018 to 2019, DiDi platform reduced the CO2 emission of its carpooling, bike, and EV services by a total of 1.3 million tons. In November 2020, in partnership with BYD, DiDi unveiled D1, the world’s first EV custom-built for ride hailing. The most recent round of funding pegged the company’s valuation at $57.6 billion.

New models are making an impact on business and climate change in other sectors as well. Indigo Ag offers farmers a package of innovative services that promote more beneficial agricultural practices (such as data-driven recommendations from agronomists and patented microbiome seed treatments) as well as data science, satellite imagery, and analytics for measuring on-farm emissions and global crop productivity. Indigo has also started a carbon offset marketplace that incentivizes farmers to use regenerative farming practices that increase carbon sequestration and reduce emissions. The resulting carbon offsets can then be sold to businesses that need them. The company has established partnerships with other companies, NGOs, and scientists to collect data, measure carbon sequestration, and quantify best practices.

Indigo Carbon, a program launched in June of 2019, helps farmers transition to regenerative growing practices that prioritize soil health and carbon sequestration, and connects them with buyers seeking to offset their carbon emissions through verified agricultural carbon credits. The program offers a unique path for sustainably minded brands to address their climate footprint and diversify their ESG strategy. The company has established partnerships with organizations across the agricultural ecosystem, including two leading GHG registries—the Climate Action Reserve and Verra—to help farmers scale the adoption of farming practices that are more beneficial for people and the planet.

Octopus Energy is an energy tech innovator providing customers with easy access to 100% renewable energy through a cutting-edge digital platform known as Kraken. The platform allows the company to pay customers to use renewable energy during periods when generation is high, thus avoiding paying higher costs when renewable supplies are low. Octopus has grown rapidly and now serves 1.9 million homes and 25,000 businesses in the UK alone. It also has operations in Australia, Germany, Japan, and the US, and it intends to reach 100 million customers in multiple countries by 2025. (It has experienced more than 400% annual growth in its customer base since 2016.) In addition to a novel technology platform, Octopus owes a good part of its success to its customer-centric approach (not always the norm in the utility industry), which delivers best-in-market service and experience. The company makes its software available to competitors in the spirit of advancing development of the climate solution ecosystem.

Incumbents have to be willing to disrupt themselves before they are disrupted by others.

California-based Pachama was started by two technologists from Argentina with the idea of using the natural strengths of forests to combat climate change. Pachama leverages two key innovations. One is using satellite data, AI, and automation to modernize carbon markets by accurately measuring the carbon store of forests in real time. The company’s AI and remote-sensing platform enables independent verification of carbon captured in forests, which allows B2B and B2C customers to measure the impact of their carbon credit investments. The other is a marketplace platform that disintermediates middlemen and makes it much easier for local landowners to certify their results and get paid for their reforestation efforts. Pachama democratizes its technology by allowing customers to access the satellite imagery and sensors that provide information on emissions and carbon captured on reforested land.

Invent. Innovations based on deep tech can generate enormous economic value, but their ultimate impact extends far beyond the financial realm to everyday life. They have the potential to fundamentally change everything from energy, transport, and agriculture to health, education, and entertainment. Deep-tech innovations can satisfy existing needs and create new models and markets , but incumbents that want to play will have to be willing to disrupt themselves before they are disrupted by others.

What Leaders Are Doing

| Reimagine | Invent |

| Didi Chuxing | Climeworks |

| Indigo Ag | Joyn Bio |

| Octopus Energy | Memphis Meats |

| Reengineer | Reboot |

| Neste | Equinor |

| Tata Group | Form Energy |

| Yara | Sila Nanotechnologies |

Consider three examples.

Joyn Bio, an agriculture technology company founded in 2017 as a joint venture between Ginkgo Bioworks and Leaps by Bayer, works to minimize the agriculture industry’s environmental footprint, starting with nitrogen. Most plants cannot use atmospheric nitrogen in its natural form, yet it is essential for healthy crop growth. The agriculture industry relies on nitrogen fertilizer to increase crop yield, but the production and use of nitrogen fertilizer generates 3% of worldwide global GHG emissions, which degrade soil, water, and air quality.

Joyn uses synthetic biology to engineer microbes that can enable cereal crops—such as corn, wheat, and rice—to fix nitrogen from the air into a usable nutrient. Joyn is developing a microbial solution that can fix nitrogen efficiently enough to reduce the use of synthetic fertilizer by 30% to 50% without affecting crop yield.

The company’s platform for microbe engineering will also be leveraged across other sustainable agriculture applications in pest control, disease management, and potentially even carbon sequestration. The innovation is made possible by exclusive access to Ginkgo Bioworks’ genetic code base and manufacturing capabilities, as well as Bayer’s industry expertise and proprietary microbial-strain library.

Growing demand for meat and livestock farming accounts for 15% of GHG emissions and 25% of earth’s available landmass and fresh water. Memphis Meats produces good-tasting and healthy meat products by harvesting them from cells instead of animals. This results in a direct one-to-one substitution for structurally complex animal meat without added antibiotics, providing healthier and safer food. At scale, eliminating the need to raise and slaughter animals will involve significantly lower caloric input and water, land, and energy use than conventional meat production.

Memphis Meats’ latest round of funding will enable the company to open a pilot plant, expected to be operational in the next 12 months. Though cellular cultivation technology is expected to cultivate edible meat while using up to 90% less land and water than conventionally produced protein, the path to commercialization will require collaboration from a full ecosystem of participants, including companies, retailers, regulators, and consumers.

Four characteristics combine to distinguish deep tech from other fields of R&D:

- They solve large and fundamental issues. Most deep-tech ventures contribute to at least one of the United Nations’ sustainable-development goals.

- They play at the convergence of technologies. Most use at least two technologies, and two-thirds use more than one advanced technology.

- They mostly develop physical products, rather than software only. More than three-quarters of deep-tech ventures are building physical products.

- They are at the center of a deep, interconnected ecosystem. About 1,500 universities and research labs worldwide are involved in deep tech, and deep-tech ventures received some 1,500 grants from governments in 2018 alone.

The biggest challenge for incumbent companies looking to invest in new solutions is developing the capability to reimagine and rethink problems. Innovation systems (whether internal or external, such as labs or incubators) need to turn their focus from executing existing solutions toward fixing new problems. Many companies should further develop their capabilities so that they can adopt scientific innovations. At the moment, for example, Fortune 500 companies devote an average of less than 2% of their revenues to R&D.

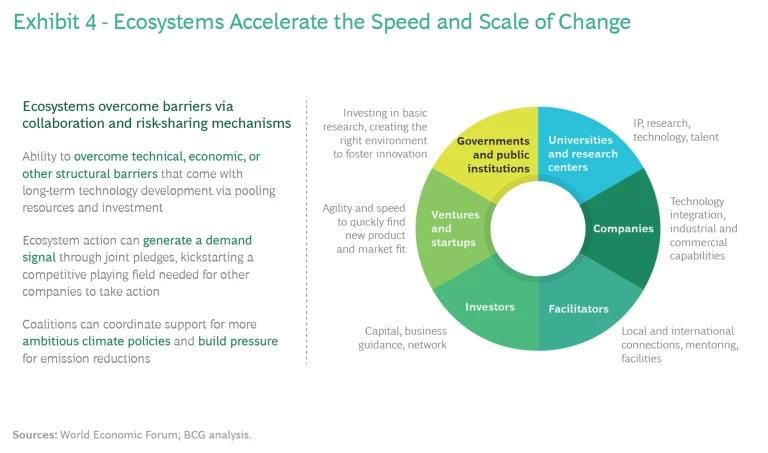

It Takes an Ecosystem

The companies pursuing innovative climate solutions will not succeed in a vacuum. Broad and deep ecosystems involving thousands of players are taking shape to combat climate change. They will be crucial for the sustainable application of advanced technologies—such as gene editing, nanotechnology, and quantum computing—that promise solutions to some of our biggest social and economic challenges. (See Exhibit 4.) These ecosystems encompass not only businesses, but investors, governments, universities, research institutions, and others, and each type of participant has a distinct and important role to play. Since ecosystems are collaborative organisms, a big part of the challenge for each player is to find the best way to contribute to the ecosystem—and profit from its participation. Here’s a brief look at the priorities for companies, investors, and governments.

Companies

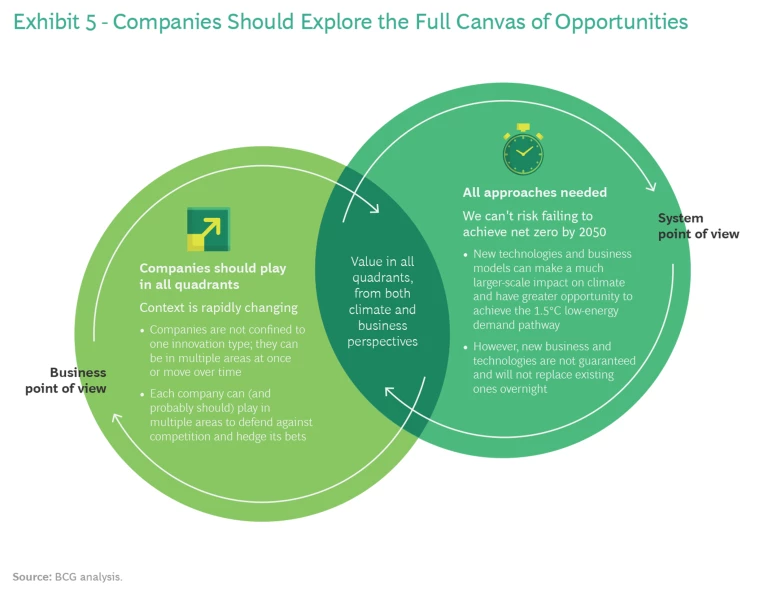

Companies are not confined to one area of innovation: they can—and should—play in multiple areas at once or explore opportunities in the four quadrants of the climate innovation canvas over time. (See Exhibit 5.) From a macro point of view, new technologies and business models can have a much larger impact on achieving the 1.5°C pathway, but these models and technologies are not guaranteed and will not replace existing ones overnight. Individual companies can defend against competition and hedge their bets by playing in multiple areas. They should apply three lenses to identify opportunities.

The first is global need: the acute climate-related threats and the way they affect customer needs and demands. How do they change the competitive environment and drive pressure on the business ecosystem to reduce carbon emissions?

The second is a company’s own strength and capabilities. What are its existing assets and expertise? Can it bring the surrounding ecosystem or partnerships to bear? Does it have the entrepreneurial culture and imperative to innovate? Has it developed a climate mission and a vision for a sustainable future?

Third is the company’s potential for impact. Can it drive both economic and climate impact? Does it have the ability to change the game?

Three Questions for Companies

Has the company developed a climate mission and a vision for a sustainable future?

Can the company drive both economic and climate impact?

These are big questions for any company, but the challenges of our time demand that businesses rise to the occasion. Existing frameworks, such as those developed under Mission Innovation’s Net-Zero Compatible Innovation Initiative, provide guidance for companies at the forefront. The ones that respond will find ample opportunities to create substantial value in the process—and reap the rewards from appreciative investors and customers.

Investors

Venture capital investment in climate technology is growing five times faster than the average rate of investment across all industries. Climate investment soared from $418 million in 2013 to $16.3 billion in 2019. We identified more than 75 funds that are already taking a variety of approaches to climate investment, including focusing on general climate technology, high-impact technology, vertical technology, and deep tech. But all this money is still a fraction of the $1.4 trillion in private equity and venture capital that was available for investment in 2019.

The various segments of the investment community can do more. Venture capital funds and their limited partners can expand their comfort zones to adopt the kind of problem-focused approach taken by most climate innovation ventures. For example, Flagship Pioneering applies a hypothesis-driven innovation process based on existing technologies to imagine products or reimagine value chains. It helped start or nurture more than 100 scientific ventures, resulting in more than $34 billion in aggregate value.

Deep-tech investors also need to reset their expectations—which does not necessarily mean accepting lower returns. They can extend fund lifetimes to allow sufficient time to de-risk R&D and launch the resulting products. They can recognize the greater complexity of technology and business models involved and spread their investments across technologies and sectors. For example, Breakthrough Energy Ventures, which has raised more than $2 billion, has a 20-year time horizon and is backed by Bill Gates and other notable limited partners, including Jeff Bezos, Michael Bloomberg, Richard Branson, Vinod Khosla, Jack Ma, Xavier Niel, and Masayoshi Son. About 90% of the company’s portfolio consists of deep-tech ventures geared toward climate change or sustainability goals, and about 50% of its staff have earned doctorates.

More funds are combining investment with active support and assistance. In 2020, Amazon unveiled its Climate Pledge Fund, a venture capital program directed at sustainable technologies. The company plans to become carbon neutral by 2040. Microsoft has created the $1 billion Climate Innovation Fund and announced that the company will be carbon negative by 2030. SOSV Investments, which invests in about 150 new startups a year, has an accelerator program that includes a network of 1,000 global mentors and an alumni community of more than 2,000 founders around the globe with deep market and technical expertise. The program provides access to an extensive infrastructure of laboratory and maker spaces, and SOSV introduces startups to sector-specific corporate partnerships and later-stage venture firms focused on the same verticals.

For their part, private equity firms can emphasize the impact of climate tech ventures on the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to their investors and the companies that they invest in. Sweden’s EQT Partners, for example, describes itself as “a purpose-driven global investment organization” that has “decided to align all investment decisions in support of achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as ownership actions to drive the development of the portfolio companies in this direction.” Private equity managers can de-risk their portfolios with ventures that will inevitably disrupt incumbents and shift or create new value pools. They can also fill gaps in skills and increase understanding of technology by building in-house expertise and networks. Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, the largest fund manager in the US, wrote in 2021 that “Climate change has become a defining factor in companies’ long-term prospects.”

The financial community needs to focus on how investors can contribute to financing the transition to new technologies and models.

Still, most investors approach the climate challenge from the perspective of environmental, social, and corporate governance goals, looking first at risk and how companies can conduct business in a long-term, responsible way. The climate solution perspective focuses first on opportunity—how companies can produce goods and services that contribute to the society we want to build. The financial community needs to focus more intently on actual results and how investors can contribute to financing the transition to new technologies and models.

Governments

Governments have been active in supporting climate solution innovation, albeit to varying degrees and with different approaches. Carbon pricing is a critical lever, but to have maximum impact, prices need to be set at the right level and uniformly applied. (In this regard, the Bank of England recently told companies to prepare for prices of $100 a ton.) At the same time, the transition to a world of low-carbon emissions is about not just individual businesses but entire integrated systems. Carbon pricing alone cannot correct for a system locked in at current emission levels. To achieve 1.5°C compatibility, governments must develop policies to exert pressure on carbon-intensive products, technologies, and practices, as well as enable, incentivize, and scale up innovations that have the potential to completely circumvent system lock-in.

Most governments can do more to enable and incentivize climate innovation, moving toward value chains and models compatible with a 1.5°C world.

In China, for example, strong government direction and support for science and technology innovation parks have led to the development of technology-focused R&D centers. One such center, Nanopolis Suzhou, hosted more than 200 private-investment firms, including numerous major international venture capital investors, and more than 300 nanotech companies in 2017.

In Europe, both the EU and national governments fund R&D for advanced technologies that contribute to climate solution innovation. The EU’s Horizon Europe program involves €26 billion for basic research, €53 billion for applied research, and €14 billion to support innovation and startups from 2021 through 2027. The purpose of the Joint European Disruptive Initiative (JEDI) is “to bring Europe in a leadership position in breakthrough technologies.” Germany’s government has agreed on a national hydrogen strategy to build up industrial generation facilities with a capacity of 5 gigawatts by 2030. Germany will provide €7 billion to ramp up hydrogen technologies and an additional €2 billion will be invested in setting up large-scale hydrogen production plants in partner countries. The new administration in the US has already signaled its intent to bring increased support for climate change initiatives.

Yet despite the initiatives underway, most governments around the world can do even more to establish policy frameworks that enable and incentivize climate innovation and reposition national economies toward value chains and models that are compatible with a 1.5°C low-energy demand world.

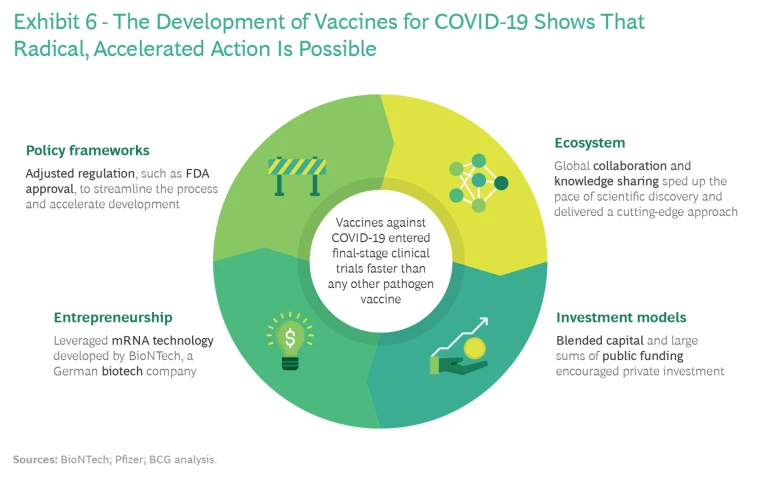

A Pandemic Points the Way

The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic has shown how quickly and forcefully companies, investors, and governments can move when called to effective action. (See Exhibit 6.) Few would have predicted a year ago that discovering, developing, testing, and bringing to market not just one but multiple vaccines in fewer than 12 months was remotely achievable or that the ways of working would change forever with digital collaboration tools—which are now the new default. Yet harnessing the power of science and advanced technology, entrepreneurship, smart policy, investment, and the collaborative efforts of the ecosystem has proven that radical progress is possible.

Climate solution innovation is no less urgent. And it offers an enormous opportunity to build economic models and individual company advantage for the long term. Until now, many companies, investors, and governments have seen climate actions and considerations as a hindrance: meeting targets could limit growth, increase costs, and cause them to fall behind competitors.

Evidence has demonstrated that climate innovation should be seen as a major opportunity to build long-term success and advantage. As Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, put it, climate change is “the greatest commercial opportunity of our time.”

The authors are grateful to the following for their input and assistance: Ajay Chowdhury, Alex Dewar, Antoine Gourévitch, Megan Moore, and David Young of BCG; Ann Mettler of Breakthrough Energy Ventures; Cilia Indahl of EQT Foundation; Massimo Portincaso of Hello Tomorrow; Edelio Bermejo of LafargeHolcim; Massamba Thioye of the UNFCCC; and Anthony Hobley of the Mission Possible Platform and the World Economic Forum.