The COVID-19 pandemic is an extraordinary black-swan event that has required companies to accomplish amazing feats in order to keep shelves full, call centers staffed, and employees, partners, and customers safe. The ability of management teams to make quick decisions with the confidence and backing of their boards of directors and chairpersons has been critical in enabling companies to adapt—a key lesson as the pandemic goes on. Because disruptions and crises will continue to occur, possibly even more frequently and dramatically than before, boards and chairs will play a crucial role in ensuring that organizations remain resilient.

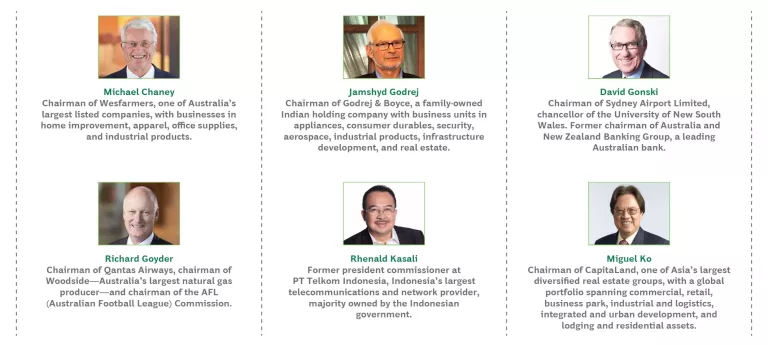

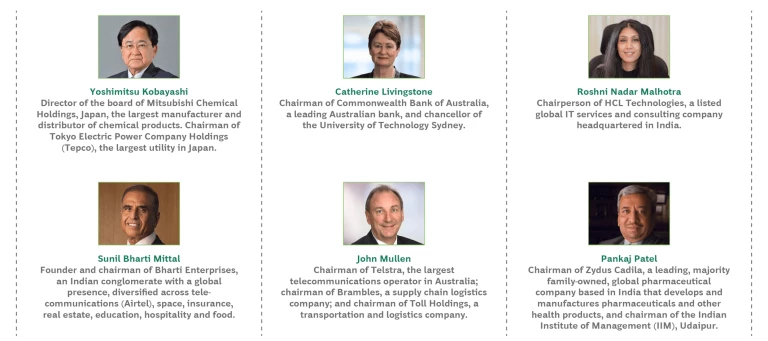

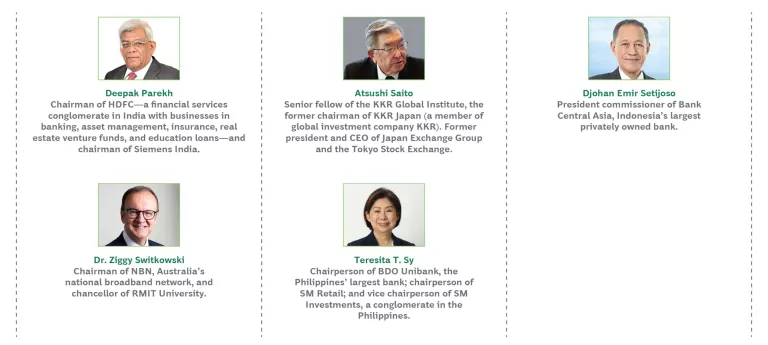

We talked to 17 leading board chairs across Asia-Pacific (APAC) to understand what they have learned so far from the COVID-19 pandemic and to identify their top-of-mind concerns for the coming recovery.

Introducing 17 Leading APAC Board Chairs

Navigating the Pandemic

For most of the chairs we spoke with, the first few months of the pandemic called for close engagement between boards and management teams and tough decisions to ensure adequate cash flow and business continuity. In some industries, such as travel and tourism , urgent measures were required for companies’ very survival. In others, such as consumer products and pharmaceuticals, unexpected growth required companies to rapidly increase capacity and address supply chain shortages.

The first few months of the pandemic called for close engagement between boards and management teams and tough decisions to ensure adequate cash flow and business continuity.

Across virtually all industries, companies focused on their people and on relationships—with employees, customers, suppliers, government bodies, and other partners. One chair whose business experienced an increase in consumer demand saw the crisis as “an opportunity to put our words—about looking after all stakeholders—into action.” The organization continued to pay furloughed employees, ensure that suppliers received prompt payments, and support nonprofit partners in its community. The chair of a company in India said that it generated better-than-expected performance by focusing on the health and well-being of employees, “motivating people and channeling it in the right way.” The approach raised plant productivity during the pandemic to the highest point in the company’s history.

We asked chairs to describe what drove their organizations’ resilience while navigating the uncertainty and disruption of the pandemic. The most common factors cited were a strong prepandemic balance sheet and a conservative debt position. But as one chair told us, resilience in a crisis also comes from “assets beyond bricks and mortar: your customers, a brand that you can trade on, and your organizational strengths and capabilities.” An established brand is important in uncertain times, when consumers revert to known, trusted options. And a strong corporate culture, grounded in a clear purpose and values, can help employees trust management to do the right thing.

An established brand is important in uncertain times, when consumers revert to known, trusted options.

Another key attribute was the extent to which the organization had already digitized its operations and modernized its technology stack, as well as having built-in redundancies, such as multisite operations and facilities enabled by technology. Many have now accelerated their digital roadmaps significantly, spurred by the pandemic-led rapid rise in digital adoption among customers, employees, and business partners. Yet organizations were generally underprepared for the extent of outages that occurred in supply chains and operations when whole countries locked down at once. For one chair, the pandemic was a “wake-up call on the fallibility of our supply chain strategy.”

Critically, many chairs attributed their organizations’ resilience to remaining alert and agile. Being alert to both acute and more long-term disruptive forces requires companies to have leadership teams and boards with diversity in experience, capabilities, and perspectives. Being agile requires leaders to be confident and able to make tough decisions—“having the guts to take a stand and do something about it”—plus the organizational ability to implement those decisions quickly.

To be clear, the pandemic is not over, and many countries are still experiencing profound effects and facing an uncertain future. But the lessons that APAC companies have learned so far will be applicable regardless of the future trajectory of the coronavirus, and in subsequent crises to come.

Three Top-of-Mind Trends for APAC Boards in the Coming Recovery

Looking to the future, chairs identified several trends that they expect to dominate the agenda for their organizations in the near term. Among the most important were:

- The growing importance of an ESG agenda and company purpose

- The digital imperative in a time of accelerating change

- Changing work models and implications for talent

The Growing Importance of an ESG Agenda and Company Purpose

In the past, environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) was treated as a discretionary activity; companies could address it at will, and many chose not to, figuring that it would be a drag on financial performance. Today, APAC chairs agree that ESG is a clear lever for improving long-term performance. This aligns with BCG research showing significant valuation and margin premiums across certain industries for companies that outperform on ESG.

“In the past, ESG just meant everything cost more,” one chair said. “You got bragging rights, but it hurt cost-wise. Now, the numbers work out well. There are lots of system benefits to pushing an ESG agenda,” continued the chair, citing investor pressure, changes in regulations, pricing, technology, and consumer preferences, especially over the past two to three years. Another chair agreed that the issue has become a central focus of the board’s work. “We probably talk more about ESG at the board table than anything else. The topic is far more significant than it was several years ago.”

We probably talk more about ESG at the board table than anything else. The topic is far more significant than it was several years ago.

What’s changed? Investors, consumers, governments, employees, and other stakeholders are putting more pressure on companies to align their business interests with community expectations. Institutional investors are spending more time and emphasis on ESG and pushing for change. Some investors are wary of emerging risks, such as how climate change will affect a company’s operations. Others—such as the large pension funds in Australia, whose invested assets are equivalent to approximately 35% of that country’s publicly traded stocks—have a broader agenda, using their significant influence to create a better future for their fund members and protect long-term returns. One Australian chair noted that some institutional investors no longer discuss financial or share price issues when speaking to the board and instead focus the entire conversation on ESG topics.

Some chairs highlighted their organizations’ longstanding dedication to ESG and community impact, which often stemmed from the values of the founder or the organization itself rather than from a response to external pressure. Not all felt this way; a few chairs said that prioritizing social issues or a company’s purpose rather than maximizing profits is a “cop-out” or an inadequate excuse for financial underperformance. These chairs believe that companies need to find a balance between economic and ESG performance. As one chair in Japan argued, the value that a company creates encompasses its contribution to solving the world’s challenges, including through ESG measures. The goal is to find an equilibrium between economic and societal value and not use efforts in one area as an excuse for falling short in the other.

An explicit focus on ESG offers another benefit: improving the company’s employee value proposition. Talent—in particular, younger employees across Asia-Pacific—increasingly wants to identify with the values and purpose of the organization. For that reason, superficial approaches to ESG will fall flat. “It’s not enough to just tick the box,” a chair told us. “ESG cannot sit outside the everyday life of a company. It has to be part of the company’s ethos, and employees need to feel a sense of ownership in every aspect.”

Sustainability hurdles will get higher and higher, not just to meet the law but also community expectations.

Another challenge for boards is risk mitigation. “Getting 99% of things right for customers is not enough,” one chair told us. “The 1% that you get wrong is where all the damage is.” Reputational risks are particularly acute given the speed with which bad news can travel and amplify via social media and other channels. “Brand image is far more fragile now,” another chair said. “There are lots of things that can cause major damage.” For that reason, boards need to ensure that they have transparency into all business practices: “Boards need to get more forensic, shifting away from averages and getting to the specifics.” This is less about micromanaging and more about asking the right questions, ensuring that specific processes and governance are in place, and gaining an understanding of any potential underlying issues.

In addition, the challenge will continue to grow, giving a competitive advantage to front runners that take a proactive stance on ESG issues. “Sustainability hurdles will get higher and higher, not just to meet the law but also community expectations,” a chair said.

The Digital Imperative in a Time of Accelerating Change

The pandemic has accelerated the already critical need for companies to digitize, and it has exposed those that were lagging far behind as digital channels and supply chain visibility and management became critical to adapting to pandemic conditions. Chairs across APAC agreed that the companies that are not digitizing fast enough are losing out, and that there is an absolute imperative for a broader digital transformation—not just for channels or supply chains. “Digitization is certainly not discretionary,” one said. “Without it we would not survive.”

More broadly, the goal is no longer to simply digitize internal aspects of an organization. Chairs called out a bigger opportunity arising from collaborating with other entities—supply chains, partners, and even customers—to digitize entire ecosystems. “The most important thing was connecting our entire sales and distribution network,” said the chair of a company based in India. This approach raises the stakes both in terms of opportunities to unlock value and of risks for organizations that don’t take action.

Though critical, digital transformations are notoriously difficult to execute successfully. Chairs we spoke with worried about the significant costs of investing in technology, the risk that it may not deliver the desired impact, and the complexity of achieving such fundamental change at scale in large, complex organizations, which are often under short-term performance pressure. BCG research has found that only 30% of digital transformations succeed in achieving their objectives and identified a set of digital transformation success factors that can dramatically flip the odds of success.

Digital transformation is not a one-time evolution to get to a new steady state. Rather, digital leaders continually innovate—with new technologies, such as advanced analytics and AI , or with business model innovation across their ecosystem—and they expect to make continuous changes over time. Successful digital transformations are table stakes for the future competitiveness of incumbent organizations, and the time frames are getting shorter. One chair noted that people used to think in terms of how a business model could change over a decade, but today, “it’s really two years—that’s the time compression we’re facing.”

For chairs of established incumbents, an important concern is whether their business models will withstand the disruption from more nimble upstarts and established, tech-oriented digital natives.

For chairs of established incumbents, an important concern is whether their business models will withstand the disruption from more nimble upstarts and established, tech-oriented digital natives. These disruptive players have inherent advantages, such as their abilities to quickly roll out offerings with global scale and reach and to reinvest cash flow in growth rather than dividends. Significantly, these companies consider data to be an inherent asset, and they focus on owning the customer relationship (and the accompanying customer preference and behavior data) rather than owning capital-intensive assets.

With this in mind, APAC chairs see two strategic paths to winning in the ’20s through digitization. One path is efficient survival: become the most cost-efficient player to provide a commoditized service. The other is growth oriented: build new capabilities and innovate in order to add value to baseline services.

One chair said, “You need to move up the value chain to increase returns and take a bigger share of the pie; those who control and aggregate the volume of customers hold the power.” This can be difficult to execute for incumbents with capital-intensive assets that will struggle as elements of their core business become commoditized. They face what’s known as the superincumbent’s dilemma : with historically high market share, profit margins, and cash flow (yet eroding growth), it is difficult to justify investments in high-growth, relatively lower-margin opportunities that typically dilute value when measured by traditional financial evaluation criteria. Successful incumbents need to potentially change their mindsets and their criteria, investing to win by moving fast and leveraging their corporate assets and developing a compelling investor relations narrative.

Digital leaders also channel a larger share of investment than others into reskilling, upskilling , and new ways of working. In Southeast Asia, one chair’s organization was ambitious about investing early and proactively in upstream talent sources throughout the pandemic. It facilitated digital adoption initiatives extensively throughout the broader community (potential future customers) and invested in digital skill-building education (potential future employees). Critical to upskilling success is finding the right balance of formal training versus on-the-job opportunities. BCG finds that upskilling programs are most successful when they follow the 10-20-70 rule: 10% theory, 20% mentoring, and 70% hands-on project delivery.

Changing Work Models and Implications for Talent

One of the more significant changes resulting from the pandemic is the shift from physical offices to remote work. Forced to make the switch virtually overnight, organizations learned, adapted, and invested in the necessary infrastructure. Many APAC chairs believe that more flexible work models are here to stay. That change will bring both opportunities and risks, as work moves from being remote by necessity to being remote by choice .

Decoupling work from location is an opportunity to dramatically expand the pool of potential talent, for a more diverse and inclusive workforce. Chairs see decoupling work from a specific office as an opportunity to dramatically expand the pool of potential talent from which a company can recruit. “Location is becoming less relevant,” one chair said. Moreover, companies can thereby create a much more diverse and inclusive workforce, enabling more caregivers (who are disproportionally women) and people who live in rural or remote locations to join the talent pool.

In addition, remote work could make flexible work schedules more feasible, also resulting in an increase in the talent pool. For example, one chair predicts the rise of a new category of talent: people who work remotely on a part-time schedule and seek 60% of the normal salary for their role. “What is considered a ‘good’ job is changing,” a chair said. “It’s no longer just about pay.” The switch to flexible work could help increase the number of women who remain in the workforce despite caregiving responsibilities, while also helping companies create more balanced leadership teams. In some countries, such as Singapore, this can enable employees to work according to their preferred model. In other places, such as India, it can help solve considerable commuting challenges that significantly diminish employees’ productivity.

At the same time, changes in work models could create unwanted divisions and tiers in the employee base, depending on whether employees’ roles require them to show up in person at an appointed time or allow them to work remotely on a flexible schedule. “We are seeing two levels of workforce even within the same company, creating a divergence in both work expectations and work ethic.” The challenge is for managers and senior leaders to pay closer attention to these issues, particularly during the transition to a new work model, and then proactively mitigate any negative impact on morale and engagement.

Another emerging issue tied to remote work is the employee experience, particularly for younger, more junior people: “It’s not a good thing to work from home all the time,” one said. “You lose the apprenticeship opportunity to learn from your boss and your peers.” Others may find that building and maintaining company cultures with a dispersed workforce may be more challenging, and team performance and engagement could suffer.

To take advantage of the best parts of a hybrid working model and mitigate the risks, companies will need to take a very intentional and holistic approach to

designing a future working model

. They will need to redesign

personalized

work models around both the type of work (for example, clerical, expert, or creative) and the type of person (young caregiver, empty nester) and work intentionally to create transparency and trust between employer and employee, rather than focus only on productivity.

Advice for Building Crisis-Proof Leadership

In addition to asking chairs to identify emerging trends, we sought their advice about how other boards and senior management could develop resilient, crisis-proof leadership. Here’s what they said:

- Make sure your board of directors has the right capabilities

- Keep ahead of new and emerging risks

- Build the capabilities to act quickly and decisively

- Engage and communicate with management more dynamically

- Know when to trust your experience and when to seek a different perspective

- Take a long-term view and drive integrity in decision making

- Most important, back management once decisions are made

Make sure that your board of directors has the right set of diverse capabilities. Boards get their strength from the collective capabilities of the participants: the broader the set of relevant skills and experience that are represented, the more effective the board will be. One chair told us, for example, of the exceptional value of having a public health expert on the board during the global health crisis. Another observed that the pandemic and the scope and pace of digitization have revealed how little some boards and committees understand technology.

Boards get their strength from the collective capabilities of the participants: the broader the set of relevant skills and experience that are represented, the more effective the board will be.

Chairs should look to expand beyond such traditional capabilities as financial and legal oversight. While it is not practical to expect all areas of expertise to be represented, boards should try to secure talent with broad, powerful skills—such as in risk management frameworks and first-principles thinking—that can be complemented by seeking outside expertise on specific topics.

In some Asia-Pacific countries, boards can be intrinsically self-limiting when it comes to membership. In Japan, for example, board members are often former employees of the organization and thus have an insider’s perspective. In India and Southeast Asia, where large, family-owned organizations are very common, the board composition is often made up of family members, although there is a strong trend towards professionalizing board membership in these geographic markets. Chairs point out the benefit of ensuring that boards have enough members from outside the organization who can bring a fresh perspective and improve the overall effectiveness of the board.

Keep ahead of new and emerging risks. Boards need to be able to identify and assess emerging risks and should scan for them proactively. Chairs have cited technology, the climate, supply chains, and geopolitics as key areas to watch. Cybersecurity was a particular area of concern among the chairs we interviewed, as were complex data governance issues, which one chair called “an opportunity for either competitive advantage or failure.” One way that prudent boards prepare for cyber attacks and other kinds of crises is by running realistic crisis simulations with both the board and the management team.

Build the capabilities to act quickly and decisively. Senior management and organizational decision-making processes need to be set up for quick reactions—both to mitigate the negative impact of disruptions and to capitalize on emerging opportunities.

“The pandemic proved that acting fast and firm trumps acting slow in the hope of getting it exactly right,” said one chair. This approach starts with senior management. “It’s more important than ever that senior executives, particularly your CEO, have the capacity to be resilient, to take knocks, and to understand that decisions need to be made in a timely way,” a chair said. “You’re not always going to get it right.” When fast-moving opportunities arise, leaders who are “not equipped to invest, or that are too relaxed” will languish, one chair said, citing organizations that have historically had a comfortable market position as most at risk.

Engage and communicate with management more dynamically. When the pandemic hit, the predictable schedule of holding regular, fixed board meetings and developing a one-year corporate plan and a five-year strategy became obsolete. As a result, boards began to interact with management teams more frequently and in a far more dynamic and informal manner. That approach was clearly a response to the uncertainty and fast decision making required during a crisis, but it generated benefits that could apply in the post-pandemic recovery period.

“More informal interactions meant that the board has been more informed and has added real value through one-to-one advice and coaching between directors and people in the business,” said one Australian chair. “The way boards work is going to change moving forward.” Another said that more frequent communication with management permits the board to “help early when companies begin to feel stress, rather than allowing problems to fester.”

Know when to trust your experience and when to seek a different perspective. The chairs we spoke with all have decades of experience running companies and successfully navigating business crises. This experience is immensely valuable, but it may not be sufficient to respond to future challenges.

Chairs cited the importance of not letting previous experience be a “concrete box” that constrains future decisions and of not limiting responses to “what we did in the past.” Another chair concurred: “Sometimes you need to forget what made you successful before. There’s no template for you to use moving forward.”

Instead, chairs told us that it’s essential to think in terms of first principles, ask tough questions, and then respond in an agile and dynamic way. Ensuring that board membership reflects a wide range of backgrounds and perspectives helps prevent making decisions based on groupthink. To that end, many chairs highlighted the importance of engaging lots of young talent. In a business environment that is changing rapidly, “you need a younger mind to understand it.” The same principle holds true for family-owned businesses. For those organizations, chairs counselled giving the reins to members of younger generations who have the right level of hunger and ambition.

Take a long-term view and drive integrity in decision making. Even as boards and management teams learn to act quickly in a crisis, they must avoid getting caught up in short-term issues. “Focus on the long term and understand that the interests of all stakeholders are central to achieving the company’s purpose,” one chair said. Another advised, “Ask the important questions of management. What are you doing to ensure that the company’s well-being is improving in every way—not just in profit or sales, but also the aspirations of all stakeholders?” Most important is to ensure that the company preserves integrity in decision making. “Do what is right,” a third chair told us. “Set a true north and hold decision-making integrity as paramount.”

Most important, back management once decisions are made. Boards serve the critical function of challenging the management team, holding them to the purpose and values of the organization and helping them set a future vision for the company. But we consistently heard from chairs that boards should not try to do the job of senior leaders.

“If you overmanage the management team, they will lose ownership, not be creative, and not take risks.” Instead, “the role of the chair is to be a custodian—not only of the values of the group but the people you work closely with.”

That is particularly true during a pandemic, given the excessive burden on company leaders. “It has been an extremely trying time for people in management and leadership positions,” one chair said. “The board needs to be custodians for them and support them and give them the leeway to do what they want to do.”

Once a decision is made, it is critical for the board to support that decision and back the management team. This gives the management team the confidence to make the critical and sometimes risky decisions necessary in a crisis, and it sends the message to external stakeholders and the rest of the organization that the board and management are aligned to lead the organization forward.

Crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic serve as a kind of crucible for boards and chairs: they introduce new stresses and challenges, and they provide an opportunity to strengthen brands, reinforce customer trust, and accelerate such organizational capabilities as risk management and digital. While the future is uncertain, all boards can learn from their experiences during the pandemic. By focusing sufficiently on such issues as ESG, digitization, and new working models, and by boosting organizational resilience, boards can ensure that their organizations are ready for whatever future challenges emerge.

The authors wish to thank Priyanka Aggarwal, Rahul Aggarwal, Reiko Akiike, Vikram Bhalla, Arindam Bhattacharya, Hans-Paul Bürkner, Colin Carter, Chaojung Chen, Arushi Jain, Yeonhee Kim, Ryoji Kimura, Carol Liao, Stefan Mohr, Zarif Munir, Rohan Passey, Rohit Ramesh, Vaishali Rastogi, Martin Reeves, Yasushi Sasaki, Ernest Saudjana, Janmejaya Sinha, Ashley Tan, David Tapper, François Tibi, Davids Tjhin, and Tom Von Oertzen for their contributions to this report.