As one type of global risk recedes, it’s a good time for CCOs and others with responsibility for compliance to get a clear view of the other challenges and opportunities they face.

Money laundering and terrorist financing. Bribery and corruption. Internal and external fraud. Business continuity risk. Climate risk. Information and cybersecurity risk. The list of crimes, risks, and other factors that bank compliance functions must track and account for grows longer and more complex with each passing year. Compliance officers today need to solve for multiple variables simultaneously. They must react to increasing pressure and high expectations from regulators and supervisory authorities, improve the effectiveness and efficiency of their compliance activities, and put data and technology to clever use. As a suddenly erupting type of risk—a global pandemic—begins to recede, it’s a good time for chief compliance officers (CCOs) and others with responsibility for compliance to take a comprehensive look at their functions to get a clear view of the challenges and opportunities they face.

Compliance officers today need to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of their compliance activities, putting data and technology to clever use.

BCG conducted a benchmarking survey in 2020 and 2021, looking into the state of bank compliance departments in North America, Europe, and Asia. As the extent and nature of risks have grown and evolved, clearer and more precise definitions of risk—and a more comprehensive approach to compliance across the entire bank—have followed. We examined both the status quo and the potential for improvement in several areas of the compliance operating model, including governance structure and reporting, the size and cost drivers, and the productivity potential for using data and technology in new or more advanced ways.

The State of Compliance Today

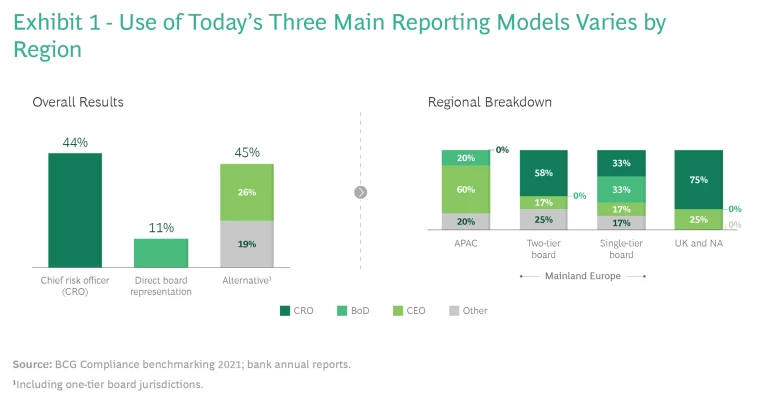

With the evolution of compliance, three main organizational models have emerged. (See Exhibit 1.) The first places compliance within the risk department (the CCO reports directly to the chief risk officer); the second involves board representation for compliance; and in the third, compliance departments report directly to the CEO or another board member. We found striking regional variations in how these models are adopted.

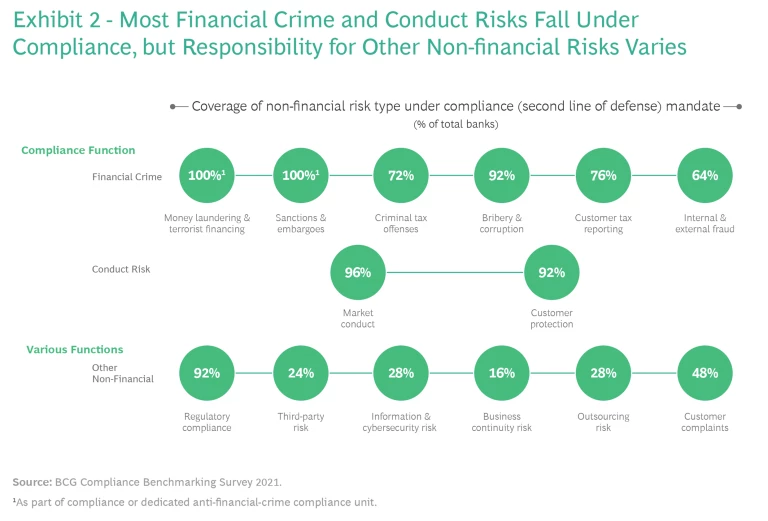

While responsibility for most financial crime risks is assigned to the compliance function, coverage for other non-financial crime risks varies substantially. (See Exhibit 2.) Financial crime and conduct risk are almost always covered by compliance, while more often than not other non-financial risks (such as cybersecurity and business continuity risk) are assigned elsewhere. As our colleagues recently observed about non-financial risk, as these risks increase in size, number, and complexity, there is a strong need for banks to take the compliance organization to the next development stage, which includes a harmonization of the risk governance and framework across all non-financial risks.

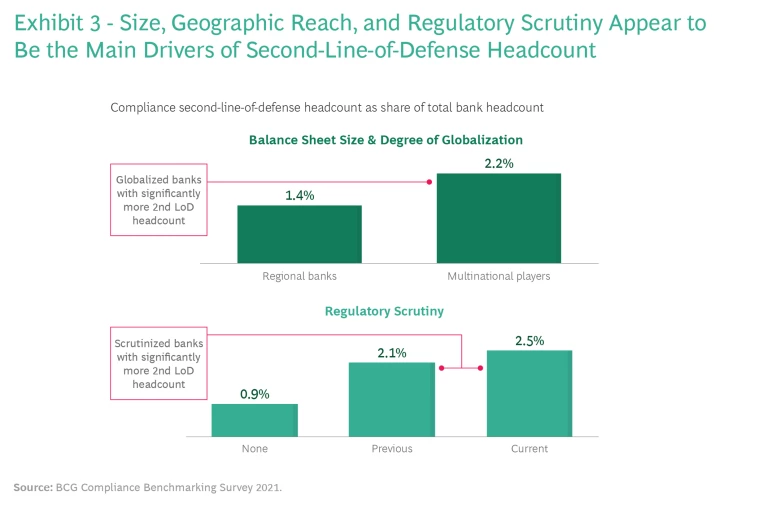

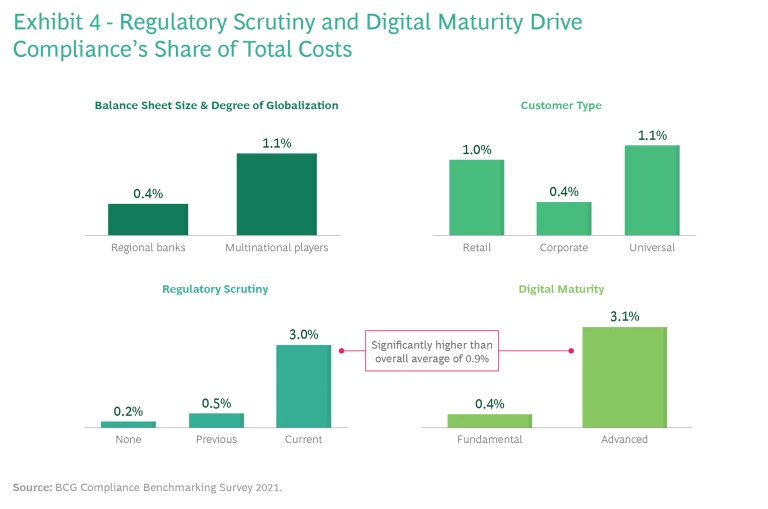

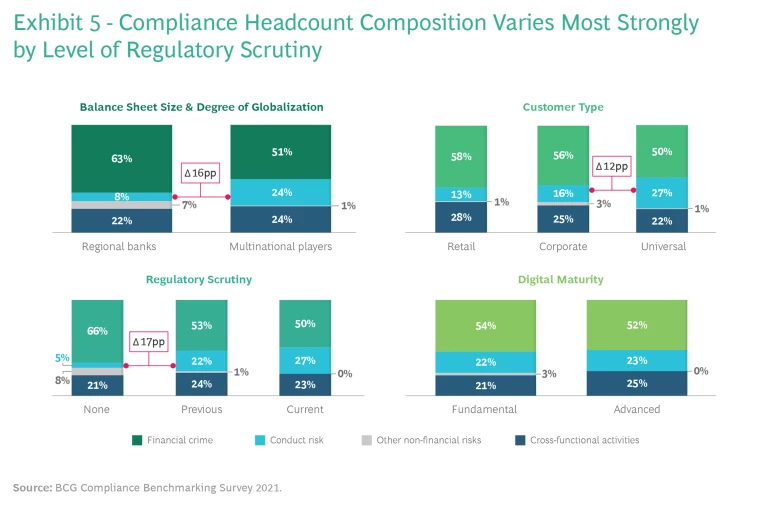

At most—if not all—banks, rising regulatory scrutiny and requirements have led to an increase in compliance headcount in recent years. The size of the compliance function appears driven by a bank’s size, its geographic footprint, and the level of regulatory scrutiny that it has experienced in the past. (See Exhibits 3, 4, and 5.) Several trends are clear:

- As banks with global footprints enter new jurisdictions, they need a minimum level of local compliance capability, which drives dedicated compliance headcount up.

- The level of regulatory scrutiny has a clear, long-lasting effect on the size of compliance functions beyond the ad hoc need for additional capacity that is common during the remediation of regulatory findings or monitorships.

- A decline in compliance staff after the end of regulatory investigations or monitorships is common; however, this reduction takes time and the resulting employment levels tend to remain higher than pre-inspection.

Among the three compliance lines of defense (the bank’s employees, its compliance and risk-related functions, and its internal and external auditors), the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing, together with sanctions and embargoes, typically accounts for the biggest second-line compliance headcount. Since multinational and universal banks tend to be active in primary and secondary markets, their corresponding larger trading activities also account for a higher share of compliance staff dedicated to conduct. Banks that are under no particular regulatory surveillance allocate considerably less staff to conduct and customer protection.

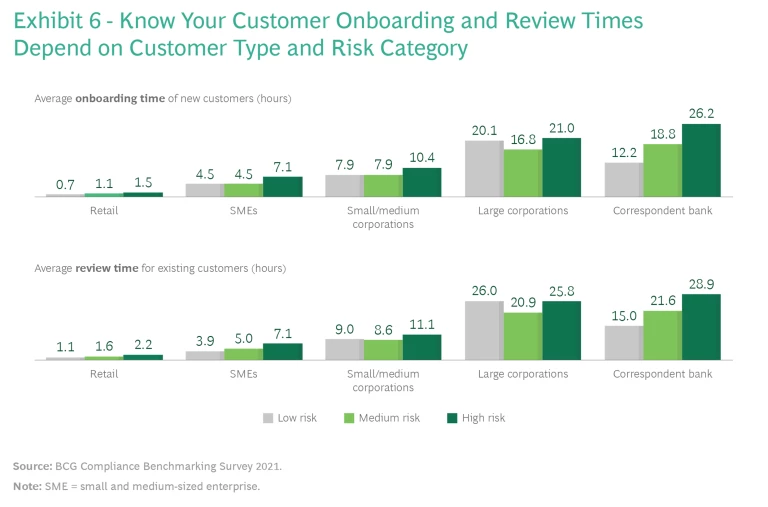

As digitization redraws all parts of the value chain, driving significant efficiency gains, it presents significant opportunities for the compliance function. For example, to achieve a real step change in efficiency, bank compliance functions should consider a full transformation of their end-to-end of people-intensive processes, such as Know Your Customer (KYC), which can be refinanced by the substantial expected efficiency gains. (See Exhibit 6.) To date, KYC programs have been focused on effectiveness. We now see an early trend toward efficiency improvements using a dynamic review model, although the change to a proactive approach is often hampered by regulatory restrictions and the complexity of conducting a full-fledged portfolio analysis and transferring master data for the entire customer base. Banks looking to make the change need to implement initial standards for adequate and effective review processes and efficient data handling. They can then show that they have established and well-run processes on which perpetual models can be constructed.

Clear Pointers for the Future

The survey provides clear pointers for the direction banks should take going forward. These include:

- Pressure testing current compliance programs

- Introducing agile into compliance

- Staying ahead of the industry curve by tackling the hot topics

Pressure Testing. The self-assessments by survey participants show a differentiated picture. Banks that are currently under regulatory scrutiny rate themselves considerably lower on such factors as culture, data, internal standards, and training than their peers. Those banks with a greater level of digital maturity rate themselves higher across almost all dimensions of the operating model. However, banks should not be overconfident about the state of their compliance organization. They should pressure test them regularly regarding effectiveness and efficiency and look for ways to increase their compliance robustness.

Banks should pressure test themselves regularly regarding effectiveness and efficiency and look for ways to increase their compliance robustness.

Agile. Compliance functions can benefit from the agile ways of working that are gaining importance at most banks. The integration of compliance into an end-to-end agile setup can help the function gain speed and efficiency while maintaining effectiveness and independence. For compliance controls, there is room for improvement.

Staying Ahead. Survey participants identified five key topics that will shape the compliance landscape over the next three years:

- Efficiency. Specific compliance use cases must be developed for both automation and advanced analytics. The most advanced banks are evolving new operating models for compliance that emphasizes these characteristics.

- Data availability. Banks need data-driven initiatives, such as analytics controls and innovative digital solutions, to remedy current data shortages or low quality of data.

- Regulatory. Recent discussion papers from the European Banking Authority and the European Central Bank, and a single rule book on centralized supervision change, indicate that ESG (environmental, social, and governance), resilience, and anti-money-laundering enforcement will be key regulatory topics going forward.

- Availability of qualified employees. Digital and analytics capabilities require employees with both vertical expertise and project management skills and classic core compliance expertise.

- Comprehensive risk assessment and oversight. Compliance and anti-financial-crime risk assessment will become increasingly data driven.

Banks need to start tackling these issues now to make their compliance functions fit for the future.

The authors are grateful to Jeanne Bickford, Christoph Brack, Markus Duram, Lorenzo Fantini, Laurin K. Frommann, Gerold Grasshoff, Max Hauser, Katharina Hefter, Laura Kiehl, Michael Kunisch, Jannik Leiendecker, Georg Lienke, James Mackintosh, Brian O’Malley, Aytech Pseunokov, Michele Rigoni, and Rei Tanaka for their contributions to this article.