Some of the industry’s top general and limited partners are working toward a standard set of metrics for tracking their portfolio companies’ ESG progress.

The pressure on companies to make progress on environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) issues has rapidly escalated within the private equity industry.

But the lack of a consistent ESG data collection and reporting framework has made it challenging for general partners (GPs) to ensure their portfolio companies are making progress on material ESG goals, to assess the link between ESG and financial performance, and to share meaningful ESG performance metrics with their limited partners (LPs), who have their own ESG investment goals. LPs, in turn, cannot benchmark the ESG performance of different funds. And portfolio companies cannot prioritize their own ESG efforts without a clear understanding of their optimal impact and value.

In short, the need for more standardized ESG reporting for private equity—something comparable to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles—has become abundantly clear. The industry itself has acknowledged this repeatedly in recent years, whether in conversations between stakeholders, in research papers and business journals, or in various public forums—including BCG’s inaugural Private Capital ESG Conference in March, where industry leaders spoke of their shared ambition to drive progress on environmental, societal, and financial value.

In response to the challenge, a group of some of the world’s largest GPs and LPs, representing more than $4 trillion in assets under management, has come together over the past several months to collaborate on a solution, with BCG supporting in the first year as a neutral partner and

The goal: ESG metrics that are consistent enough to establish meaningful benchmarks but flexible enough to allow room for continuous improvement.

Participating GPs would still transmit this data directly to their own LPs, but they would agree to use the same definition and methodology for these selected ESG data points; they would also agree to anonymize their portfolio companies’ ESG data points and aggregate them centrally in order to form industry-wide insights into the relationship between private equity ownership and ESG performance, and potential correlations with financial outcomes.

In this article, we describe the ESG data challenges the private equity industry faces, the process behind our efforts to drive progress on both data collection and actual ESG performance, and the results of the ESG Data Convergence Project to date.

The Challenge

GPs and LPs looking to assess ESG performance are well aware of the numerous difficulties they face. First of all, the sheer number of competing public and for-profit frameworks—an alphabet soup that includes SASB, GRI, SBT, CDP, TCFD, PRI, UN SDGs, EU SFDR, and WEF

No single framework, however, offers standardized guidance to private companies on which ESG criteria to track and report, or benchmarks against which they can fairly and consistently compare their progress. New standards are multiplying, and PE firms are becoming overwhelmed with ESG data requests. One GP included in our research reported that it received 37 separate ESG data requests from LPs in a single week.

There is currently no ESG framework specifically designed for the needs of PE firms and their LPs.

Moreover, different frameworks have their own goals and stakeholders, and thus require a wide variety of metrics and KPIs. Some are focused on regulations, others on reputational issues, and still others on reporting requirements. Some are tied to specific business models, some collect only publicly available data, and some depend entirely on qualitative answers to questionnaires. None is specifically designed for the needs of PE firms and their LPs—to collect the meaningful data that will allow them to assess and compare the ESG performance of both large and small private companies, how the performance of those companies has changed over time, and the impact of ESG progress on financial results.

Indeed, the lack of standardization makes it especially difficult to compare ESG performance against financial outcomes. ESG data today is frequently qualitative, which is inherently hard to correlate with quantitative financial data. Without a robust set of standard ESG data points, it is impossible to normalize data (by industry or headcount, for example) or to rigorously assess where and how performance on specific ESG dimensions may correlate with drivers of financial performance.

Finally, the lack of quantitative ESG performance data makes it hard for PE firms and their portfolio companies to drive material ESG improvements. As the adage goes, “what gets measured gets managed.” Quantitative data can help identify areas where improvement is needed, provide incentives to improve, and track progress over time.

First Principles

In its effort to overcome these challenges—and recognizing that its methods and metrics would require continued evolution and expansion—the ESG Data Convergence Project began with five guiding principles:

- Data first. The group was focused, first and foremost, on collecting meaningful, usable quantitative data from day one. In fact, participation in the effort was predicated on a willingness to share historical ESG data on all the metrics chosen and to change internal systems to collect the chosen metrics in the same format for 2021 and beyond.

- Collaboration. In order to create a broadly appealing solution, the group prioritized open collaboration between GPs and LPs to ensure that the needs of all stakeholders would be addressed. The more attractive the solution, the more GPs and LPs would participate in the effort, generating even more meaningful data and creating a positive flywheel effect.

- Think big, start small. By starting with a small but meaningful core set of metrics that could already be measured accurately by many portfolio companies, the group aimed to ensure rapid progress and momentum to enable future ambitions.

- Dynamism. The focus was on progress, not perfection. The group designed an annual process for reviewing progress, setting new ambitions, and evolving metrics over time. The goal: to maintain alignment with regulatory changes and other market forces.

- Open invitation. In order to quickly generate critical mass, any GP or LP ready to help develop and agree to a standardized set of metrics can join in the 2021 collection effort as a first-year member of the ESG Data Convergence Project, or in subsequent years once ready. (See the sidebar, “How to Get Involved.”)

How to Get Involved

- Visit this website for more information about the initiative, including how to participate. There will be several informational sessions held in the fall of 2021.

- Contact the ESG Data Convergence Project with any questions.

- For GPs and LPs: Confirm your participation by agreeing to the terms in the commitment survey.

- Additionally for GPs:

- Complete the benchmarking agreement for 2021 on the above website and submit it via secure link.

- Download the data guidance and standard reporting template and adapt your internal data collection system to align with the initial core metrics.

- Complete 2021 data collection by April 30, 2022.

Defining the Data

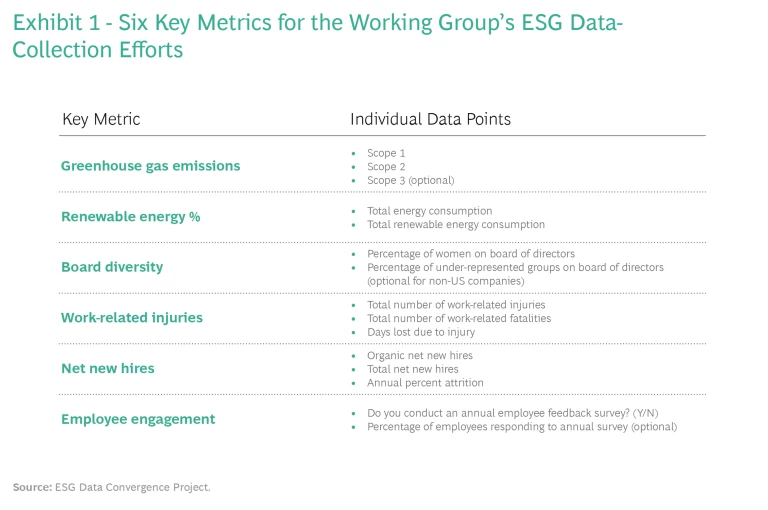

In keeping with these principles, the group agreed that they would begin by collecting an initial set of six metrics from their portfolio companies for the calendar year 2021. (See Exhibit 1.) These metrics would be collected at the same time of the year, using the same technical definitions, and normalized with a standard set of non-ESG data points, including revenue, enterprise value, and others. The data would be shared with participating LPs invested in the underlying funds in a standard format to enable comparability across their GPs, and it would be centrally aggregated by a neutral third party—for the first year, BCG—to create relevant benchmarks and to drive research.

These initial metrics were chosen according to the following guidelines:

- Globally Accepted. All data points were selected from the most accepted and widely regarded frameworks.

- Meaningful. Data points were chosen to have the greatest financial or social impact, although some may be specific only to certain industries.

- Comparable. Each data point allows performance comparisons between portfolio companies and across GPs, with adequate overlap across industries.

- Dynamic. Metrics are expected to evolve over time, as tracking gets better and understanding of their importance evolves.

- Straightforward. Data are simple to track accurately, with a limited number of total metrics, so as not to overburden companies with reporting requirements and to maintain data quality and integrity.

- Actionable. All metrics should be tied to specific actions GPs and companies can control.

- Objective. Metrics should minimize subjectivity and the need for interpretation.

For the most part, the metrics chosen adhere closely to these guidelines. Board diversity and employee engagement are easy to track, highly meaningful, and actionable, for example. Others, such as greenhouse gas emissions, are more challenging to measure accurately. Still others, including employee engagement metrics, were included in part because many GPs already track them, given their material correlation to financial performance. (More details on the metrics can be found here.)

Still, GPs have found it a challenge to gather the necessary metrics from their portfolio companies, many of which are still building the capabilities and new data platforms needed to report these metrics accurately. Reporting resources at both GPs and portfolio companies continue to be spread thinly across multiple reporting frameworks. And the sheer number of requests for inconsistent ESG data puts an added burden on GPs and their portfolio companies alike.

Our hope is that a consistent, meaningful range of ESG metrics will encourage and enable GPs to work effectively with their portfolio companies to gain the expertise needed to maintain and report on their ESG progress regularly.

Initial Insights

In addition to deciding on 2021 as the first year to start collecting the complete set of ESG data, the group agreed to conduct an initial test of the agreed-upon metrics. To that end, they asked participating GPs to provide historical ESG data from 2018 to 2020 across a pilot group of nearly 100 portfolio companies across 18 countries and close to 40 different industries.

This pilot dataset was dependent on the availability of comparable historical ESG data; as such, it is less complete and robust than the 2021 and future data will be. Even so, the exercise revealed several useful insights and trends regarding the progress PE-owned companies are making toward their ESG goals, and how their progress compares with public companies.

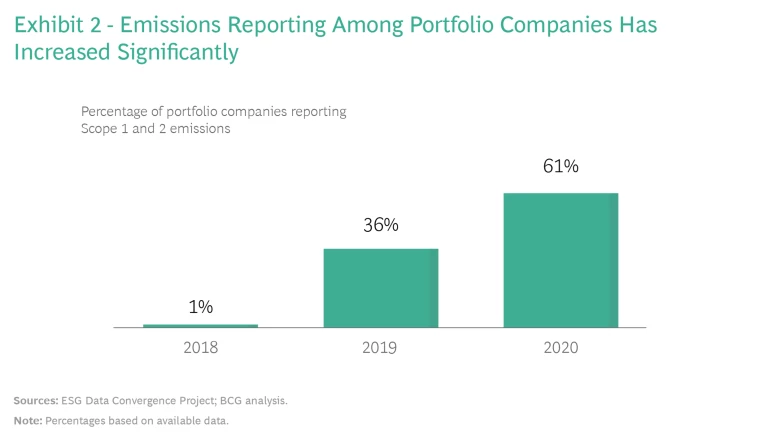

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions disclosure. Emissions disclosures present a prime example of GPs mobilizing to produce transparent and quantifiable ESG data. In 2018, only 1% of the portfolio companies in our pilot data set reported on their Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions; in 2020, that number increased to 61%. (See Exhibit 2.) All participating GPs will be requesting this data from their portfolio companies in 2021.

While we must be cautious about extrapolating very far from the data gathered in the pilot, these findings call into question some beliefs about private equity. For example, some have raised concerns that as increased regulatory pressure and disclosure requirements affect public companies further, private equity could become a safe haven for high-polluting divestments. Yet we found that the private equity-owned companies in our sample have been generally willing to increase their quantitative GHG emissions disclosures, a key finding for all asset owners. Additionally, we found no significant difference on average between private companies’ emissions intensity—amount of GHG emissions per dollar of annual revenue—and that of public companies when segmented by emissions scope.

We believe that private equity can be a responsible home for underperforming assets, including those divested from public companies, and that it can make the necessary multiyear investments to improve portfolio companies’ emissions intensity as well as their financial outcomes. As our dataset grows, we will be able to more fully assess future trends in emissions intensity over time.

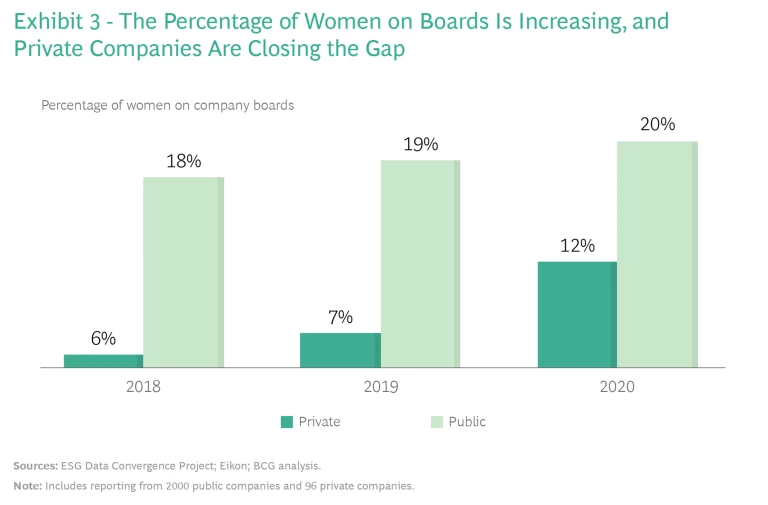

Board gender diversity. In 2018, women accounted for just 6% of board members among the portfolio companies reporting on this metric. But the number has grown quickly since then, doubling to 12% in 2020. While this lags public companies, the percentage of women on boards at private companies is growing faster than at their public counterparts—and the gap is narrowing. (See Exhibit 3.)

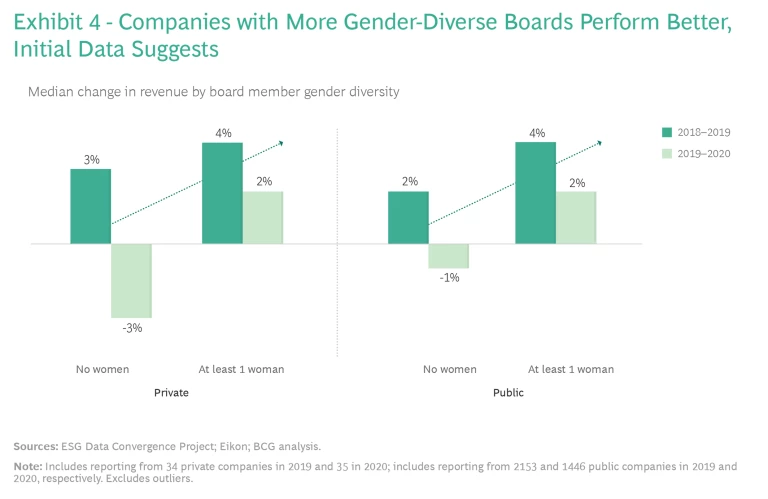

Moreover, the median private company in our dataset with at least one woman on its board saw higher revenue growth relative to the median private company with no women on its board across 2018-2019 and 2019-2020. (See Exhibit 4.) Further data in subsequent years will be required to strengthen this observation; however, it does suggest that the efforts of this data project should help establish more specific links between ESG metrics and private companies’ financial performance.

The majority ownership position that most PE companies take enables them to have more control and flexibility to bring in the right talent, not only at the board level but also within the C-suite. We anticipate that in future years this group will add additional metrics to link C-suite and company diversity with better financial outcomes, as prior research has suggested.

These initial results suggest three key early insights into the role of private equity in promoting ESG goals among private companies:

- Once they decide to begin tracking meaningful ESG data, private equity firms can move quickly, significantly increasing disclosure rates among their portfolio companies.

- Private equity firms can also make rapid progress toward improving their portfolio companies’ performance in the areas measured—potentially even faster than their public counterparts.

- Aggregating ESG and financial data across multiple GP portfolios could establish correlations between ESG metrics and specific financial outcomes, enabling robust and powerful data-driven insights across the private sector.

Conclusion

The many benefits of consistent, standardized, regularly measured ESG data—for GPs, LPs, and their portfolio companies too—cannot be disputed. The efforts of the ESG Data Convergence Project, we believe, will significantly increase the ability of all stakeholders not just to gain insights into critical dimensions of ESG performance. They will also increase ESG accountability among private companies and ultimately improve their performance in critical areas such as carbon efficiency, board diversity, worker safety, and others.

The more private equity stakeholders can work together, the more data, stronger insights, and better answers we will have to answer for the ESG questions that matter—and the more progress the field can drive on meaningful ESG issues.