Transformation is a critically important topic in the public sector—and its relevance hit home during the past year. As COVID-19 put extreme stress on governments, many of them responded speedily and at scale. They experimented and innovated. They streamlined bureaucratic processes and introduced new and previously unimaginable ways of working.

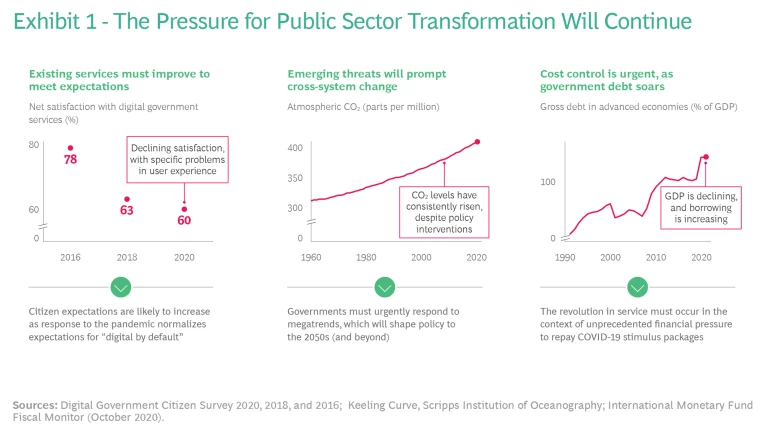

These transformative moves were necessary in the teeth of a crisis. But transformation can and often should be a choice. The forces that precipitated transformation before the pandemic remain in play and may have intensified. Overall satisfaction with digital government services is declining. The climate goals of the Paris agreement remain distant. Government debt is soaring in response to emergency spending during the pandemic. (See Exhibit 1.)

Unfortunately, a common “transformational playbook” for public sector organizations does not exist. Such organizations vary vastly in type, size, and mission. They also have different goals and different starting positions in talent, skill, technology, and work habits. Following the retirement of the space shuttle program in 2011, the Kennedy Space Center in Florida needed to transform its mission or, potentially, wind down operations. The situation that leaders faced there differs considerably from the one faced by the Indian government in pursuing its desire to transform procurement of $400 billion in goods and services a year.

Public sector organizations have the capacity to transform. They can identify root causes, mobilize their people through the power of purpose, fix what is wrong, and strengthen their ability to engage in continual cycles of renewal. Although there is no playbook, the public sector has seen plenty of successes that can inform tomorrow’s

- Take stock of reality.

- Select the right approach.

- Build the future.

- See it through.

Take Stock of Reality

Transformation is much more than a cost-cutting exercise. In the public sector, it often involves becoming more digital, agile, and responsive to the public while attracting and retaining the right talent. It may depend on fully engaging the people within the organization. For that to happen, leaders must invest time and energy in articulating and bringing to life the purpose of both the organization and the transformation. Purpose is the fundamental “why.” It is what gives employees a reason to show up to work with energy and commitment.

The power of purpose cannot be overemphasized, as the leaders of the Kennedy Space Center realized after the space shuttle was permanently grounded. The center had excess capacity and 50 years of knowledge and experience but no obvious purpose.

Leaders decided to break the bonds of the past. They broadened the fundamental mission of the center to support commercial launches. This was a high-stakes transformation that required alignment among leaders and fundamental changes in mindset, culture, behavior, operations, regulation, and ambition.

Today the center is leaner and flatter than before. It is customer oriented and commercially oriented, hosting 20% of all space launches. And it is helping the US maintain its competitive edge in space while also providing strong economic multiplier effects to the central coast of Florida. It is an independent government agency operating with its jets at full throttle.

Acting on an understandable desire to fix things quickly, the Kennedy Center’s leaders could have decided to shrink in size and stature. Instead, they went big because they wanted to stay relevant.

At the outset of a transformation effort, leaders should convincingly answer some simple but powerful questions:

- Nature of Change and Scale of Ambition. Are the vision and the goal of transformation clear, compelling, and outwardly focused? How different is the shift in strategy or practice from whatever is in place today?

- Speed. Is time a constraint, or is there breathing room? An organization in crisis may have months, not years, to make a difference. Other organizations may want to transform quickly but nevertheless require a multiyear program to make a difference.

- Scope. Is the entire organization in play? Does the transformation apply to a specific sector or to the whole of government? An NGO operating in war-torn or impoverished areas faces different challenges from a domestic social services agency.

- History and Culture. What is the organization’s record in similar efforts in the past? As the novelist William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” If the organization’s transformational record is mixed, leaders should figure out what went wrong previously and figure out ways to ensure that this time will be different.

- Capabilities. Does the organization have the right talent? Arguably, the public sector needs new digital skills and less hierarchical ways of working even more than the private sector does. Improving service delivery and speed—a top priority—depends heavily on hard-to-find tech and agile skills.

- Legitimacy. Does the organization have the legitimacy, or underlying support, to act and the ability to maneuver within labor, regulatory, or legislative constraints?

The answers to these questions—which are likely to differ from initial assumptions—determine the actions to emphasize and the proper order in which to address them. It makes sense to go slow early in order to go fast later. This is the first secret of public sector transformation.

All transformations, private or public, operate within constraints. Success depends on how the organization addresses these constraints, not on whether they exist.

For example, early in the transformation of HM Courts & Tribunals Service (HMCTS), the organization—which runs courts and tribunals in England and Wales—proposed short timelines to fit with budgetary cycles. Upon reflection, however, its leaders realized that they would need to lengthen the timelines to meet their ambitions. They created a more expansive digital program, designed around the needs of the public, improving efficiency and access to justice.

After the onset of the COVID-19 lockdown, HMCTS did not have the luxury of time, but it did have the benefit of its preparation of the prior transformation. It moved swiftly to increase the use of virtual and remote hearings, and it opened temporary “Nightingale Courts.” It also delivered home COVID-19 testing kits to court employees and participants who would be appearing in person.

Absent the modernization that had already occurred, large parts of the system would have been in danger of grinding to a halt during the pandemic. For example, the Special Educational Needs and Disability Tribunal was able to run completely remote hearings from the very start of the pandemic, having already moved all of its paperwork online.

Whether launched in an emergency or after careful deliberation, transformations require alignment and extraordinary effort. If leaders treat the transformation as business as usual or with half-hearted commitment, so will their employees.

Select the Right Approach

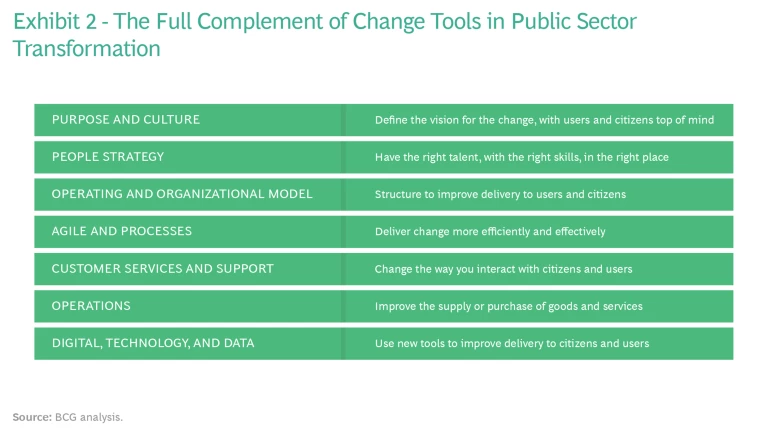

The second secret to overseeing a successful public sector transformation is to understand what needs fixing and then to choose the right tools for the job. By identifying root causes, organizations can select the correct mix of tools, which may range from operating and organization model changes to digital, technology, and data investments. (See Exhibit 2.)

Picking the right set and sequence of tools is both a science and an art. Digital government programs, for example, require changes in people practices and skills, whereas operational transformations tap into technology, digital, and data. Many organizations work on public services and support at the same time as digital, technology, and data, but not all do. No two transformations will apply these levers in exactly the same way.

When the change is large and disruptive, transformation may entail building something new. That happened in India when the government initiated efforts to transform its $400 billion annual procurement spending. Leaders quickly realized that the existing processes were too broken to permit easy correction.

Procurement cycles took months. Because many purchases were local, the government couldn’t flex its purchasing power or its platform’s potential to match faraway buyers and sellers. Leakages were all too common. With public procurement accounting for nearly 20% of GDP, the problem was also so big that getting the fix wrong could be disastrous.

In response, the government created the Government e-Marketplace (GeM), an online marketplace for commonly used governmental goods and service. This standalone unit invested heavily in technology, digital, data, and people. It also changed processes to make HR practices and pay standards more flexible in order to attract best-in-class digital talent. The government then supported the marketplace with strong marketing and simpler procurement processes designed to eliminate red tape.

The transformation is paying off. Procurement cycles times now are up to 20 times faster than under the previous system. The government has saved nearly $1 billion, or 15% to 20% of online purchases. It expects to spend $90 billion on goods through the marketplace by 2026. As the cost of doing business on GeM continues to decline, the platform is attracting more participants. During the pandemic, GeM also quickly pivoted to offering COVID-19–related supplies.

Another example of a government selecting the right approach involves Service New South Wales in Australia, which radically streamlined and consolidated a wide range of services from different agencies into a one-stop shop. Borrowing heavily from leading practices in retail, banking, and other industries, Service NSW completely changed its business model for delivery, creating a new customer experience for transactions such as renewing a driver’s license.

Today, citizens of New South Wales can conduct thousands of transactions from 35 agencies in any of 110 storefronts, a single call center, or a common online portal. Previously, they had to navigate 400 service centers, 102 call centers, 900 websites, and 8,000 telephone numbers. Satisfaction among both citizens and employees rose substantially during the rollout. About half of the people in the state have created online accounts, and about a third have visited at least one storefront kiosk. Service NSW is now creating completely new offerings, such as a cost-of-living service to help citizens discover and enroll in governmental assistance programs.

Build the Future

Transformations require the backing of a rock-solid plan that delineates a series of specific goals. Leaders should focus on devising a simple framework that makes sense of the hundreds or even thousands of strands of necessary work. They should aim to make the aspirational operational. At its core, the plan must include three critical components that run in parallel:

- Create momentum. Organizations should make short-term moves that establish momentum, both to demonstrate to employees and the public that the transformation is real and to free up resources to fuel greater ambitions. This element is critical in public sector organizations that must cope with competing priorities and limited funding and resources.

- Focus on the medium term. After establishing momentum, organizations must rethink their operating and delivery models to improve service to the public. The effect of this transformational work should be to give the organization a lift for at least three to five years. Positive effects that last for any shorter period are simply not worth the effort needed to achieve them.

- Sustain the change. Transformations should strengthen the organization. Unless the right team, structure, operating systems, and culture are in place, the transformation will be short lived. For public sector organizations, sustainability often means working in a more streamlined, more engaging, and less bureaucratic way.

Public sector organizations cannot transform by tackling these elements casually or sequentially. They can’t wait to generate savings before working on the medium term. They also need to start building the post-transformation organization at once, or the transformation will never end.

Building for the future is hard, but the rewards can be spectacular, as South Korea demonstrated in its response to COVID-19. South Korea’s success in combatting the virus has been exceptionally good, in part because it applied lessons that it learned in fighting the outbreak of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015. The MERS epidemic hit South Korea harder than it did any other country outside the Middle East, with 185 confirmed cases and 38 deaths. The spread of that virus demonstrated a number of challenges that the nation faced in coordinating government and nongovernment agencies. Afterward, a joint investigation with the World Health Organization yielded recommendations to strengthen the public health capabilities and leadership at the Korean Center for Disease Control (KCDC).

In response, the KCDC undertook wholesale reform. It engaged in reflective learning and analyzed the root causes of its inadequate response to MERS. It then ran continuous improvement exercises, using simulations to test response plans and investing in areas that had fallen short, including communications and data and analytics.

The first test for the transformed KCDC came in 2018, with the reported diagnosis of a single MERS case in South Korea. Remarkably, the nation kept the case count at one.

When COVID-19 emerged, the KCDC was prepared. As of February 2021, the nation had a COVID-19 fatality rate of just 32 per million people, and only 0.18% of the population had tested positive for the coronavirus. These results are more than an order of magnitude lower than those reported in nations such as the Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US. And South Korea achieved these results without having to impose a national lockdown.

See It Through

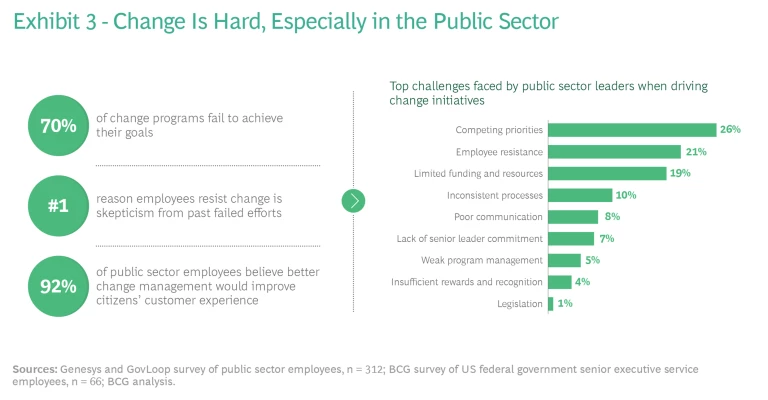

The final secret of public sector transformations is rigor toward process, progress, transparency, and especially people. Sustained change is difficult—increasingly so in the public sector. Leaders face problems with competing priorities, employee resistance, limited funding and resources, inconsistent processes, and poor communication. (See Exhibit 3.)

The best programs tie together three types of journeys: of leaders, programs, and people. They identify and empower the right leaders within the organization to drive change; they create an activist program management office to track initiatives, increase transparency, and measure impact; and they ensure that employees are prepared for the change. Too often, an organization’s people receive the least attention. Our research shows that organizations that ace the people side of transformation perform twice as well as lower scorers on that dimension of change.

The public sector is being called upon to do more with the resources available to it. That situation is not likely change. Organizations that want to be effective in 2020s must be ready to transform themselves in order to improve their service to citizens.

The authors thank Grant Freeland, BCG senior advisor and transformation expert, for his invaluable contributions.