Open-market business models—including exchanges, platforms, and hybrids—can transform the US health care industry, leading to more efficient, convenient, and cost-effective care.

Though hospitals and health systems in the US use cutting-edge technologies to offer world-class clinical care, they still rely largely on traditional business models. Open-market approaches based on exchanges, platforms, and hybrids are beginning to reshape this delivery paradigm. These models enable providers and patients to interact more like buyers and sellers, leading to more efficient, convenient, and cost-effective care. (See “How Exchanges, Platforms, and Hybrids Work—and How They Differ.”)

How Exchanges, Platforms, and Hybrids Work—and How They Differ

Exchanges

Exchanges bring suppliers and consumers together to facilitate easier and better transactions. Pure exchanges have no inventory, do not create products, and do not curate or deliver services. They facilitate exchanges between buyers and sellers in ways that increase transaction ease, transparency, and efficiency. For example, Hotels.com is a digital exchange that neither owns nor operates hotels. It also does not curate, select, or tailor the rooms listed on its service. It simply provides a transparent digital exchange where hotels can offer some of their inventory and consumers can select and reserve a room with minimal friction.

Platforms

Platform companies bundle goods and services to create seamless offerings for consumers. A platform company can be both a producer and an aggregator of supply, aligning offerings from both internal and external sources. Unlike exchanges, platform companies curate their offerings to maximize their attractiveness to potential customers. They enhance their value by putting together the right mix of owned, outsourced, or partnered services to create the best offering at the right cost.

Target, for example, like many other retailers, has built a platform that combines brick-and-mortar stores with a digital presence to sell an array of products and services, including its own private-label brands and third-party offerings. It curates all offerings and has in-store partnerships with other retailers, such as Apple and CVS. But it is not an exchange. Suppliers are not free to sell their wares, and consumers do not transact directly with suppliers. Instead, Target manages the platform and aligns supply with demand to enhance value for its consumers.

Exchange-Platform Hybrids

Sometimes exchange businesses evolve into platforms, or platforms incorporate exchange models. Like exchanges, these hybrid models facilitate transactions between third parties and consumers. Like platforms, they also incorporate branded and third-party products and services in an integrated customer offering. The larger system meets consumer needs in multiple markets through multiple channels and business models.

Amazon, for example, began as a digital exchange focused on one product: books. As its distribution prowess, market clout, and consumer and product knowledge grew, Amazon evolved its exchange to include other products from independent suppliers, along with Amazon-branded goods. Apple, in contrast, built its exchange business, the App Store, to enhance the value of its computers, smart phones, tablets, and watches by facilitating transactions between third-party app developers and consumers.

Unlike platforms, hybrid companies do facilitate some direct transactions between suppliers and consumers. Unlike pure exchanges, hybrid companies curate and align their offerings to improve value for customers. They analyze transaction data to enhance innovation and gain a competitive advantage over rival businesses and even their own suppliers and partners.

Exchanges and platforms have already proven their worth in other industries, such as retail, travel, and media. Until recently, however, such barriers as high regulation, limits to access, and complex billing have prevented health care organizations from capitalizing on new business models. As exchanges, platforms, and hybrids begin to take hold, they could disrupt traditional business models and launch a new era of consumer-friendly health care. New entrants are gaining share with compelling offerings. The rapid adoption of digital technologies during the pandemic, along with changing consumer expectations and regulations that mandate transparency and data sharing, all add momentum to this shift.

Exchanges, platforms, and hybrids could disrupt traditional business models and launch a new era of consumer-friendly health care.

To respond, incumbent health care companies must understand this trend and reconfigure established business models by embracing consumerism and developing their own exchanges, platforms, and hybrids. Cautious incumbents may choose to launch pilots or forge partnerships to test the value of the new models as a first step. One thing is clear, however: if incumbents do nothing, they risk a slow decline into irrelevance.

A Model Proven by History

In the Middle East, thousands of years ago, commerce exploded when intersecting trade routes gave rise to covered markets known as bazaars or souks. These markets created an exchange for buyers and sellers to execute transactions more efficiently. That simple model has been wildly successful across centuries and cultures for remarkably diverse products and services. More recent examples include farmers markets, classified ads, message boards, and digital exchanges, such as eBay and Craigslist.

From the earliest bazaars to today, the same principal dynamics of exchanges apply. Suppliers gain cost-effective access to consumers, who in turn get convenient one-stop shopping with multiple offerings and prices. Exchanges reduce the friction that impedes commerce and give consumers more access, selection, and control. This shift of power unleashes competitive market forces, putting enormous pressure on suppliers to upgrade their offerings and adapt their pricing.

Modern digital technologies turbocharge these dynamics by significantly increasing access, convenience, and speed, powering the rise of such exchange-based titans as Uber and Airbnb, which have reconfigured supply-demand relationships throughout the global economy. Airbnb now lists more properties than the six largest hotel chains combined. Its market capitalization now exceeds more than $100 billion, roughly equivalent to the combined valuations of the four largest hotel chains (Marriott, Hilton, InterContinental, and Hyatt).

The Vulnerability of Traditional Health Care Businesses

The US health care industry is late to the game, largely because powerful forces have impeded changes to traditional models. Specific barriers include the following:

- Industry incumbents hold significant legislative and regulatory clout.

- A small number of payers and providers dominate concentrated markets.

- Complex billing and reimbursement structures are hard for patients to understand—a vulnerability that could be easy for payers and providers to exploit.

- Transparent information about outcomes, prices, and customer satisfaction is limited.

- Third-party payments for medical claims complicate buyer-seller dynamics.

Slowly, these barriers are giving way, and health care is beginning to adopt more innovative approaches to connect providers and patients. The specific benefits of exchanges and platforms—including increased consumer choice, competition among suppliers, and reduced friction in transactions—line up neatly with the pain points of the health care industry. Transaction costs are high, and prices are mystifying. Choice is limited. Customers are often frustrated by the process of accessing care. Some providers are highly inefficient, with opaque processes and technology that significantly lags behind that in other industries.

The benefits of exchanges and platforms line up neatly with the pain points of the health care industry.

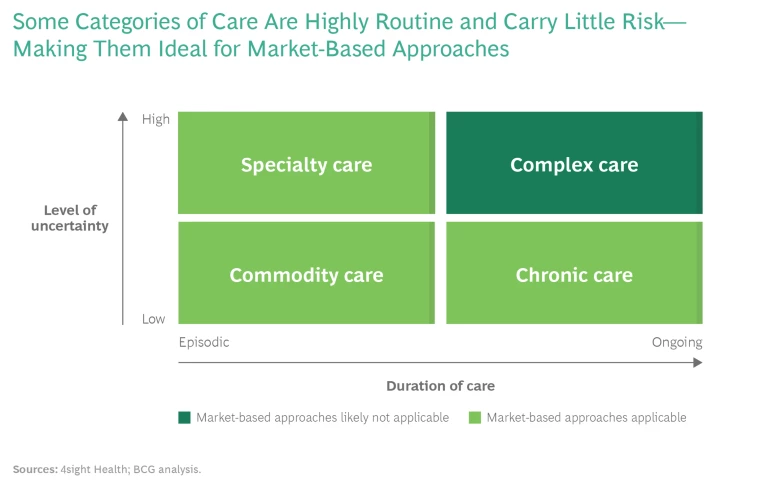

Perhaps the biggest factor in favor of exchange and platform models is the fact that, contrary to popular belief, most health care services are highly standardized and commodifiable, with little to no inherent risk. Patients may not be able to act as consumers and make their own choices in situations involving highly specialized and complex care, but they can do so for situations involving routine, nonacute chronic care and most specialty care, which account for most patient needs. (See the exhibit.)

Commodity care could include a wide variety of routine care, such as wellness exams, vaccines, and such standard surgical procedures as joint replacements and heart bypass surgeries. Chronic care for long-term conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes, often involves highly defined, preset procedures that can—and should—be more competitively priced and delivered through a much better customer experience than most providers currently offer.

The provision of commodity and chronic care is beginning to shift to asset-lite providers that offer services in convenient, nonacute settings. Compared with hospitals, these providers can deliver commodifiable care services in lower-cost settings, including clinics, urgent care centers, and even patients’ own homes. And technology—such as app-based interfaces, remote monitoring, and virtual care delivery—can increase the capacity of decentralized services to accommodate consumer needs quickly, conveniently, and cheaply.

Most specialty care is also moving to high-volume facilities that can deliver consistently higher quality outcomes at lower costs. As a result, consumers can base their health care decisions on factors such as price, convenience, and customer experience.

As consumers become increasingly acclimated to making routine care decisions for themselves, exchanges become a more efficient way to access a range of service providers, compare offerings, and simplify transactions. In turn, exchanges empower consumers and intensify competition among providers.

Disrupting the Status Quo

Over the past decade, a few first movers have launched digital exchange companies with B2C offerings for routine procedures. These exchanges provide one-stop shopping (price comparisons, scheduling, and prepayment) for self-paying customers—a small but growing market segment.

For example, Nashville-based MDsave, founded in 2011, allows patients in 35 states to book routine health care services online. Patients can log into a user-friendly portal to access an expansive menu of diagnostic tests and procedures encompassing 42 specialties. Consumers can price shop, schedule appointments, and make payments, including discounted prepayments. The company entices providers to join its network by offering incremental patient volume and quick payment, eliminating the payment hassles that are a major source of frustration among providers.

Similarly, Dallas-based ColonoscopyAssist, founded in 2010, offers consumers transparent, low-cost gastrointestinal (GI) screenings in more than 30 states. Like MDsave, ColonoscopyAssist offers one-stop shopping, education, scheduling, and payment through its portal. The company appeals to providers as a quick and reliable source of referral care through hundreds of GI centers nationwide.

Transcarent, a new Chicago-based B2B exchange, raised $58 million from investors in June this year. Transcarent’s model, still in development, will incorporate prenegotiated prices for more than 300 types of surgeries at prequalified centers of excellence.

Through the Transcarent portal, members will control their entire health care experience. The Transcarent app will connect users to doctors through live video within 60 seconds. For more serious conditions, Transcarent will create personalized care roadmaps that guide users to reputable doctors and hospitals.

The company is marketing simultaneously to businesses (the lucrative self-insured employer segment), their employees, and providers. As such, it poses a greater disruptive threat to status-quo business practices than B2C exchange companies do. Yet it will still offer exchange-type benefits, connecting providers with more patients and rewarding superior-care outcomes.

Members can select the care they need on their terms, with no premiums, copays, or deductibles. For employers, Transcarent’s value proposition is compelling. The company receives payment only when it delivers quality treatment outcomes at lower costs. This strategic approach replicates the business practices of exchange companies that have disrupted the travel industry, such as Expedia, Kayak, Orbitz, and Travelocity.

MDsave, ColonoscopyAssist, and Transcarent all give health care consumers easier access to the services they want at transparent, competitive prices. They succeed by catering simultaneously and without bias to both buyers and sellers of health care services.

How Incumbents Can Respond

Exchange companies represent a powerful and distinctive new business model for executing health care transactions, and among incumbents, multiple segments are vulnerable. As exchanges gain share, the prices for routine services—including MRIs, colonoscopies, and high-volume surgical procedures, among others—will drop. Traditional service providers that cling to fragmented, high-cost, fee-for-service delivery models will lose margin and market share to competitors with lower prices; more convenient, higher-quality service delivery; and a superior customer experience.

Traditional health care organizations should consolidate and develop more comprehensive service platforms that integrate their own services with offerings by third-party vendors.

Traditional health care organizations have no choice but to adapt. As incumbents in other industries have done, they should respond to these new competitive threats by consolidating and developing more comprehensive and compelling service platforms that integrate their own services with offerings by third-party vendors. Some proactive health systems are now building platforms in primary, urgent, home, and hospice care, as well as imaging, testing, and telemedicine services, among others.

Hartford HealthCare (HH), for example, is an integrated health system in Connecticut. The company has reorganized its services along the full continuum of care, from acute care to senior living, accessible within a seamless digital platform for consumers. HH produces some of these services internally. It offers other vital services through strategic partnerships, such as with GoHealth Urgent Care, a national provider.

As they develop and implement exchanges and platforms, incumbent providers should focus on several core principles:

- Create the widest possible variety of services and focus on delivering the highest quality outcomes at the lowest prices, particularly in commodity, chronic, and specialty care.

- Make the offerings accessible through an intuitive digital interface (including mobile), allowing consumers to serve themselves whenever and however they choose.

- Offer advanced analytics to help consumers make better health care decisions quickly and easily.

- Make pricing transparent. Just as in the travel industry, health care will start to see side-by-side price comparisons for routine services.

- Focus on the customer experience throughout.

To date, entrenched incumbents have exercised sufficient market power to prevent exchanges and platforms from offering convenient high-value health care services to consumers. But the competition is growing, enticing consumers with lower prices and an improved customer experience while also granting participating providers easier access to those consumers.

Given this shift, legacy health care organizations have a choice. They can cling to their suboptimal, status quo business practices—and watch their market share decline as they continue to frustrate patients and providers alike. Or they can rethink their business model by proactively developing consumer-friendly platforms that enable them to compete effectively. In doing so, they can participate in—and lead—the transformation of health care in the US.

The authors thank Julia Eleuteri for her contributions to this article.