COVID-19 has added to the woes of a global oil and gas sector that was already struggling with persistently low total shareholder returns (TSR). (See “The Components of TSR.”) Starting in early 2020, the pandemic unleashed the largest oil and gas demand shock in history. Social distancing and national lockdowns brought economies to a standstill, sending oil prices tumbling. Oil and gas companies’ share prices and earnings followed in short order.

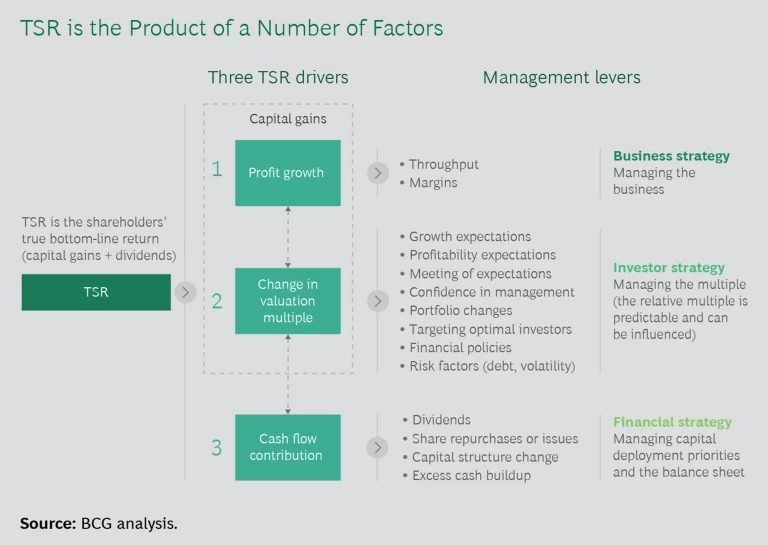

The Components of TSR

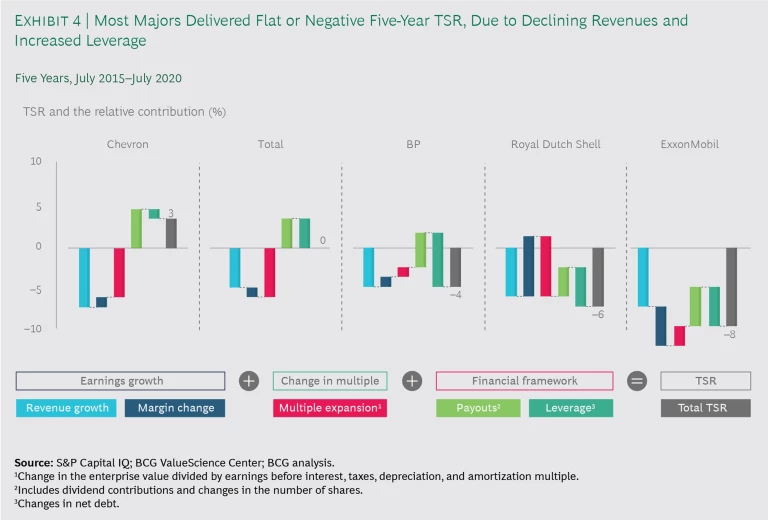

Our approach deconstructs TSR into a number of underlying drivers. We use a combination of revenue growth and margin change to assess changes in fundamental value. We then factor in the change in a company’s valuation multiple to determine the impact of investor expectations. Together, these two factors determine the change in a company’s market capitalization and investors’ capital gain (or loss).

Finally, we track the distribution of free cash flow to investors and debt holders in the form of dividends, share repurchases, and repayments of debt, and we determine the contribution of free cash flow payouts to a company’s TSR.

For Big Oil, 2020 wasn’t just about the harsh business environment. The pandemic has caused international oil companies (IOCs) to accelerate their plans to reinvent themselves for a new energy landscape. With less capital available to spend, decisions on how to allocate it have become starker. As a result, a clear split has emerged in companies’ strategies for the future, with significant implications for value creation.

On one side of the strategic divide, European IOCs are ramping up their expansion into renewables and low-carbon energy businesses in pursuit of growth. On the other, their North American peers are focusing on what they know best, doubling down on oil and gas production while investing in technologies to increase efficiencies and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

But regardless of their approach, neither group has yet to prove to investors that it can create sustained value. Boston Consulting Group’s survey of 150 oil and gas investors worldwide , conducted in October 2020, found that two-thirds of shareholders expect demand to return to pre-COVID-19 levels in the second half of 2021. They also expect prices to rise.

60% of investors in our survey expect the sector’s median TSR over the next two years to be no higher than it was over the past two years.

Nevertheless, few investors expect companies to capture this upside, with 60% predicting that the sector’s median TSR over the next two years will be the same as or even lower than it has been over the past two years. To overcome this perception, companies must make fundamental changes across their businesses that transform investor sentiment and drive a share valuation rerating.

Oil and Gas Has Fallen Behind Other Sectors

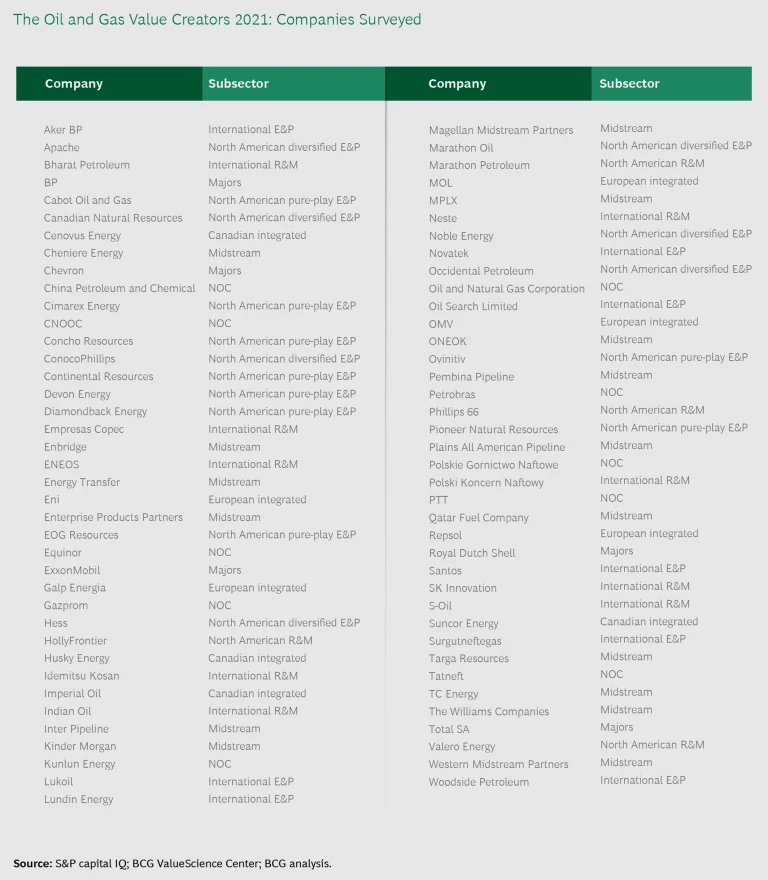

In this report, we analyze the historical TSR performance and key valuation drivers of both global and regional players, with a particular focus on the majors—the five largest publicly traded integrated IOCs. (See “Companies in Our Sample.”) We examine the ways past and present strategies have impacted returns and suggest steps to create future shareholder value.

Companies in Our Sample

Each company in the sample was valued at more than $6 billion (as of January 1, 2020), had a free float of at least 20%, and existed prior to 2015. The companies we studied had a combined enterprise value of $3.2 trillion as of July 31, 2020. Of this figure, the majors accounted for approximately 28%, national oil companies and midstream companies about 20% each, exploration and production (E&P) companies around 15%, refining and marketing (R&M) companies roughly 11%, and other integrated players about 6%.

Our study looked at TSR performance over a ten-year price cycle from July 2010 through July 2020. Furthermore, we examined value creation over three- and five-year time periods. These analyses provided additional insights into how companies’ performance changed during different oil price and market environments.

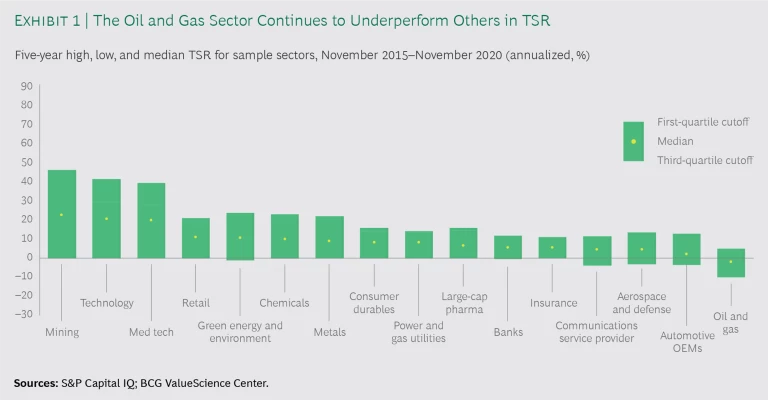

Value creation among leading oil and gas companies has been unimpressive for several years. Despite a late-year 2020 rally, the oil and gas sector delivered median annualized TSR (share price appreciation plus dividends) of –2% for the five years from November 30, 2015, through November 30, 2020, and still finished in last place among the sectors that BCG looks at. (See Exhibit 1.) For the industry’s biggest players—the majors and other leading IOCs—median annualized TSR has remained in the third and fourth quartiles, when compared with the constituents of the S&P 500 Index, over one-, three-, five-, and ten-year time frames. (See the appendix for details of the top 20 oil and gas TSR performers over these time periods.)

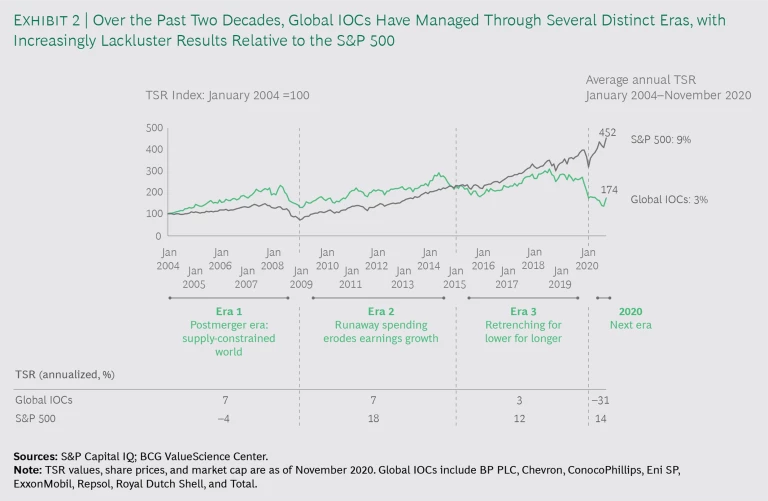

Changes in strategy and external factors help to explain the sector’s underperformance. Until the 2008–2009 global financial crisis, rising global demand and limited supply buoyed oil and gas prices, resulting in good earnings growth, strong balance sheets, and steadily greater dividend payouts. Starting in 2009, however, companies overinvested in higher-cost assets, which delivered weaker returns and tarnished the industry’s reputation as a responsible steward of shareholder capital.

As the US shale boom reached its zenith, it flooded energy markets with abundant supplies of oil and gas, leading to a steep drop in prices in 2014 that undermined the IOCs’ profitability. Companies responded by cutting costs, making portfolio decisions on the basis of value rather than volume, and increasing borrowing. By 2019, the environment had changed again. Even before the pandemic, growing investor concerns about peak oil and gas demand, the industry’s GHG emissions, and competition from renewable energy sources were weighing on share prices.

In tandem with changing strategies and new pressures, IOCs’ TSR performance has steadily worsened over the past decade as companies, faced with diminishing profits, have come to rely more on quarterly dividend programs to prop up their share prices and create value for investors. Their dependence on payouts as the main driver of TSR has resulted in higher debt and caused them to rank poorly against companies in other sectors that offer investors access to a broader value creation proposition.

After outperforming the S&P 500 in annualized TSR over the prior five years, global IOCs achieved a median annualized TSR of 7%—less than half that of S&P 500 constituents—from January 2009 through December 2014. And from January 2015 to the beginning of 2020, the IOCs’ median annualized TSR fell to 3% versus 12% for the S&P. (See Exhibit 2.)

Revenues and Debt Were Key Drivers of Five-Year TSR

Over the five years ending in July 2020, the sector’s strongest performers delivered revenue growth while keeping debt levels stable. As a result, dividend payouts were less important in driving value creation for these TSR leaders, which included international exploration and production (E&P) players and national oil companies.

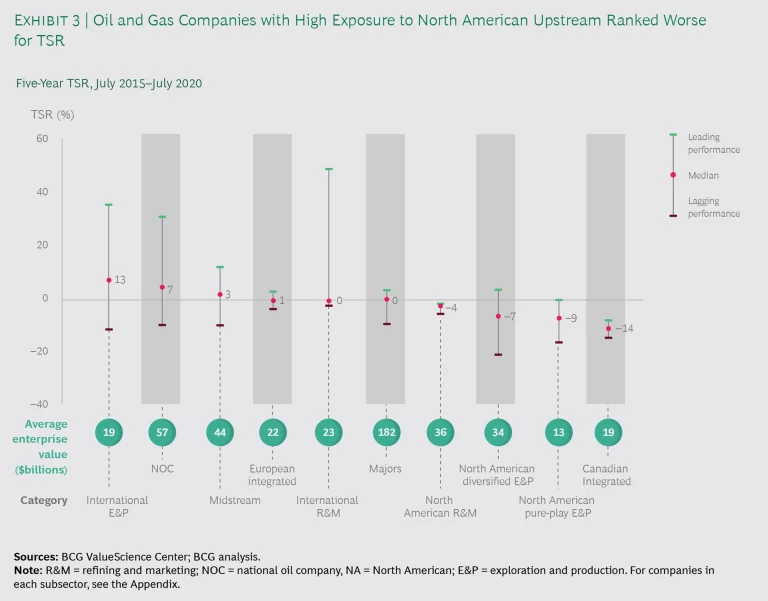

In contrast, North American E&P and Canadian integrated players were the main laggards, owing to a vicious cycle of poor earnings—caused primarily by low oil prices—that resulted in higher debt. (See Exhibit 3.) Because of their weakened share prices, these two peer groups have recently been at the leading edge of an M&A drive toward more basin-level consolidation, both as targets and acquirers. Consolidation offers the opportunity to take out cost and increase scale efficiencies, thereby driving future earnings growth. Higher oil prices in the future, due in part to insufficient investment by oil and gas companies in their upstream operations , might also provide an earnings boost for players across the sector.

Over the most recent five-year period, declining revenues and rising debt hindered the majors’ TSR performance, although Chevron still managed to rank among the top 20 oil and gas companies for shareholder returns. (See Exhibit 4.) Overcoming these two hurdles remains a serious challenge for companies seeking to create shareholder value. Oil and gas companies are failing to generate competitive TSR compared not just with other sectors but also with players operating in different areas of the energy industry, such as renewables developers.

The Importance of Dividends During the Pandemic

The pandemic caps a challenging decade for oil and gas, which has seen investor interest in the sector wane. The share of oil and gas companies in the S&P 500 is currently about 2% of the index’s total market capitalization, down from about 16% in 2008. As individual companies’ market capitalization has shrunk, comparative newcomers have overtaken former stock market giants. In Europe, the market cap of Danish offshore wind company Orsted has surpassed that of BP; and in the US, NextEra—another energy company with a strong renewables presence—briefly surpassed ExxonMobil and Chevron in October on the same measure.

In 2020’s challenging and uncertain business environment, the US’s Chevron and France’s Total were the TSR winners among the majors. Although share prices of all the IOCs fell sharply during the year, these two companies had the necessary balance sheet strength to maintain quarterly payouts—despite pursuing widely differing portfolio strategies. Their valuation multiples (measured as enterprise value divided by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) also held up better than their peers’ valuation multiples did.

Indeed, a robust balance sheet and the ability to maintain dividend payouts were key differentiators between the TSR leaders and the laggards in Europe in 2020. For oil companies BP and Royal Dutch Shell, cutting the dividend removed a key support for their share prices and TSR. Shell’s stock fell by about 16% in the week following a two-thirds reduction in the payout on April 30 (it announced a modest increase in October to placate investors). BP’s stock also underperformed after it cut its dividend by 50% in early August and provided further details about its transformation from an IOC into an integrated energy company, which it had initially announced in February 2020. Both stocks approached 25-year lows in early November before regaining ground later that month in the wake of positive news about progress toward COVID-19 vaccines.

Unlike BP and Shell, Total’s relatively modest debt position and portfolio bias toward barrels with a low breakeven point enabled the company to avoid a damaging dividend cut. At the same time, a lower dividend yield allayed investors’ concerns about a future reduction. As a result, the company outperformed its peers on share price and TSR. Total has indicated that it can continue to fund capex requirements without seeking external equity or debt financing even if oil prices fall to $25 per barrel. And it can meet capex and dividend payments on the same basis with oil at $40 per barrel.

US Majors Showed Differing TSR Performance

Although ExxonMobil, the US’s largest IOC by revenues, maintained its dividend payout, it trailed Chevron and Total in TSR in 2020—and the other four majors over the most recent five-year time frame. One important reason: other majors compensated for declining revenues relatively early by aggressively cutting costs across their business units and thereby boosting profit margins, but ExxonMobil took comparable steps later on. As a result, the company’s free cash-flow yield has deteriorated in recent years and was the lowest of the majors for the 12 months through December 2019.

Over the past ten years, ExxonMobil’s net debt has risen as the company has continued to fund capital expenditures and generous quarterly dividends despite weakening sales. In a rearguard response to the pandemic-induced decline in oil and gas prices, the company in April cut 2020 capex by 30%. It reduced future capital spending in late November and announced that it was writing off between $17 and $20 billion in investments primarily in US natural gas projects, several months after other majors had taken billions of dollars in impairment charges.

ExxonMobil still enjoys a higher valuation multiple than its peers. But Chevron, the company’s biggest US rival, is catching up, thanks to its stronger balance sheet and clearer ability to fund future dividends. ExxonMobil’s rising dividend yield suggests that shareholders have doubts about the certainty of future payouts, putting pressure on the company’s multiple. In a sign of where investor priorities lie, US activist funds reportedly urged ExxonMobil in December 2020 to cut costs and curb its spending, over concerns that its dividend was at risk.

Four Actions for European IOCs

Owing to the market turmoil caused by COVID-19, maintaining dividend payout levels was a key path to delivering peer group-leading TSR. But the pandemic had other important impacts as well. Several European majors revised their outlook for future oil demand downward, partly in response to the pandemic. Lower expectations for crude have caused these players to alter their attitude toward renewable energy and view it as an opportunity rather than a competitor.

BP plans to build 70,000 electric vehicle charging points by 2030, up from 7,500 today.

European IOCs are reinventing themselves as broad-based energy companies in order to benefit from higher valuations and more positive investor sentiment toward alternative energy. They are expanding into growing low-carbon markets in renewables, hydrogen, and biofuels. They are leveraging existing customer-facing businesses to unlock value from new forms of energy consumption. For example, BP plans to build 70,000 electric vehicle charging points by 2030, up from 7,500 today. And they are growing their integrated gas businesses because the fuel has a more favorable outlook than crude oil in their medium- to long-term forecasts.

European IOCs will need to take several steps to ensure a smooth journey as they continue to transform.

Maximize returns from hydrocarbons. US players aren’t alone in needing to improve returns from their upstream oil and gas operations . European companies must make similar reforms if they are to fund their transformation into energy companies, meet debt reduction targets, and pay the dividends that investors crave. They will have to generate these returns while grappling with an extremely difficult macroenvironment. So-called high-grading (in which producers concentrate their efforts on the most profitable fields) will help. But companies must also make their operations more efficient and reduce emissions, using new technologies to curb methane leaks and digitize important areas of the business. They must ensure that these measures receive sufficient resources and management attention despite other pressing priorities.

Prove the business case for low-carbon investments. In our investor survey, shareholders expressed enthusiasm for clean energy investments. Their expectations for the sector’s TSR, however, suggest that they are skeptical about companies’ ability to turn a profit from them. There are clear reasons for this skepticism. Although low-carbon investments generally have better growth prospects, returns on individual projects tend to be lower than for traditional oil and gas production. And because these businesses are closer to utility businesses, managing them requires a different mindset. As European IOCs pivot away from hydrocarbons, they will need to persuade investors of the long-term benefits of evolving from oil and gas producers into energy companies—and of the companies’ ability to deal with challenges along the way.

Efficiently allocate capital across the portfolio. European IOCs will also need to spend large sums on M&A to move the dial on alternative-energy investments. Most would have to invest around $5 billion a year to make a difference to group-level returns. But suitably large acquisition opportunities are scarce, and high prices for sought-after assets could erode investment returns. Companies will have to allocate capital efficiently if they are to scale up their low-carbon investments in a way that doesn’t erode the value of these new businesses and at the same time provides sufficient funding for their oil and gas operations.

Optimize the shareholder payout strategy to boost TSR. In the wake of the pandemic, European players have developed a range of approaches for rewarding investors. Some plan to grow the dividend, while others have announced their intention to hand back surplus cash by repurchasing investors’ shares rather than raising payout levels. These approaches will have different effects on value creation. In our experience, buybacks are less effective than dividends as a way to boost TSR because they are less predictable and because, in the absence of dividends, companies must resort to other TSR levers, such as earnings growth and changes in their valuation multiple. Investors concur: in our October 2020 survey, respondents said that they preferred reasonable debt levels and dividend growth over buybacks. Taking the right approach will be essential if companies are to secure investor support for the future.

In our October 2020 survey, respondents said they preferred reasonable debt levels and dividend growth over share buybacks.

Four Actions for North American IOCs

For the most part, North American IOCs are focusing on the traditional oil and gas businesses where they have existing expertise and well-defined capabilities. Rather than moving aggressively into new low-carbon areas, they are developing plans to curb GHG emissions across their businesses.

These players still enjoy higher multiples than their European counterparts, thanks to their stronger balance sheets and track record on payouts. But to generate the healthy returns they achieved in the past, irrespective of oil price movements, they must build greater financial resilience by improving the efficiency of their operations and driving down costs.

Here are four specific actions that North American companies can take to create greater value for shareholders.

Transform the core. Companies can’t afford to wait for the reemergence of higher prices to promote earnings growth. They must adopt a transformation agenda that drives continuous improvement throughout the organization. This agenda should cover multiple aspects of the transformation process. For starters, companies should strengthen governance of capital allocation decisions. They should also take steps that deliver operational benefits, such as introducing value-creating digital technologies, adopting more agile ways of working, and developing new types of collaborative relationships with their key suppliers.

Future-proof the hydrocarbon portfolio. Oil and gas producers must prepare for a more carbon-constrained world by improving their portfolios’ resilience to changing demand, growing concerns about climate change, and the likelihood of higher taxes and increased regulation for heavy GHG emitters. To secure investor support—and benefit from a potentially higher multiple—companies must develop meaningful emissions reduction plans and demonstrate progress toward meeting emissions targets. The US majors have lagged behind not just European IOCs but also several larger North American E&P players in creating GHG reduction programs. Exxon-Mobil recently responded to this need by unveiling tougher plans in December 2020. All companies should consider whether their targets are sufficiently demanding to maintain backing among investors that are already concerned that decarbonization will lead to stranded hydrocarbon assets. They should also run projections to see how their portfolios perform under different regional and global scenarios involving changes in demand, regulations, and markets, and use their findings to drive smarter capital allocation decisions.

Build and scale new businesses. Although North American companies will continue to focus primarily on oil and gas in the near term, they need to respond to the changing energy landscape by developing material businesses in new areas. They should explore opportunities to invest in low-carbon hydrogen, which holds the key to decarbonizing large sectors of the global economy, and in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) . The introduction of a more generous federal tax credit in the US has improved the commercial viability of CCUS in enhanced oil recovery, which relies on CO2 to increase the amount of oil extracted from a reservoir.

Use a tactical approach to M&A. We expect M&A to play an important role as companies seek to strengthen their position in key basins. Consolidation will enable companies to create value through enlarged revenues and reduced costs and to acquire cleaner, more resilient assets. As they consolidate, North American E&P players have a significant opportunity to drive TSR by cutting administrative, nonproduction costs. In the second quarter of 2020, the 35 largest independent E&P companies in the US spent 15% of their revenues on selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses, compared with the US majors’ figure of just 7%. All players will have to use M&A tactically to gain a specific end and seize opportunities as they arise.

Global energy systems are changing irreversibly. Oil and gas companies will need to be ready to compete in a bigger arena against a broader array of energy providers, with TSR performance as the yardstick. As they prepare for the new energy landscape, they must place shareholder value creation at the heart of their strategies if they are to win the future.